Surveying

Surveying is the technique and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional space position of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually, but not exclusively, associated with positions on the surface of the Earth, and are often used to establish land maps and boundaries for ownership or governmental purposes. In order to accomplish their objective, surveyors use elements of geometry, engineering, trigonometry, mathematics, physics, and law.

An alternative definition, per the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping (ACSM), is the science and art of making all essential measurements to determine the relative position of points and/or physical and cultural details above, on, or beneath the surface of the Earth, and to depict them in a usable form, or to establish the position of points and/or details.

Furthermore, as alluded to above, a particular type of surveying known as "land surveying" (also per ACSM) is the detailed study or inspection, as by gathering information through observations, measurements in the field, questionnaires, or research of legal instruments, and data analysis in the support of planning, designing, and establishing of property boundaries. It involves the re-establishment of cadastral surveys and land boundaries based on documents of record and historical evidence, as well as certifying surveys (as required by statute or local ordinance) of subdivision plats/maps, registered land surveys, judicial surveys, and space delineation. Land surveying can include associated services such as mapping and related data accumulation, construction layout surveys, precision measurements of length, angle, elevation, area, and volume, as well as horizontal and vertical control surveys, and the analysis and utilization of land survey data.

Surveying has been an essential element in the development of the human environment since the beginning of recorded history (ca. 5000 years ago) and it is a requirement in the planning and execution of nearly every form of construction. Its most familiar modern uses are in the fields of transport, building and construction, communications, mapping, and the definition of legal boundaries for land ownership.

Contents |

Origins

Surveying techniques have existed throughout much of recorded history. In ancient Egypt, when the Nile River overflowed its banks and washed out farm boundaries, boundaries were re-established through the application of simple geometry. The nearly perfect squareness and north-south orientation of the Great Pyramid of Giza, built c. 2700 BC, affirm the Egyptians' command of surveying.

- The Egyptian land register (3000 BC).

- A recent reassessment of Stonehenge (c.2500 BC) indicates that the monument was set out by prehistoric surveyors using peg and rope geometry[1].

- Under the Romans, land surveyors were established as a profession, and they established the basic measurements under which the Roman Empire was divided, such as a tax register of conquered lands (300 AD).

- The rise of the Caliphate led to extensive surveying throughout the Arab Empire. Arabic surveyors invented a variety of specialized instruments for surveying, including:[2]

- Instruments for accurate levelling: A wooden board with a plumb line and two hooks, an equilateral triangle with a plumb line and two hooks, and a reed level.

- A rotating alhidade, used for accurate alignment.

- A surveying astrolabe, used for alignment, measuring angles, triangulation, finding the width of a river, and the distance between two points separated by an impassable obstruction.

- In England, The Domesday Book by William the Conqueror (1086)

- covered all England

- contained names of the land owners, area, land quality, and specific information of the area's content and habitants.

- did not include maps showing exact locations

- Continental Europe's Cadastre was created in 1808

- founded by Napoleon I (Bonaparte), "A good cadastre will be my greatest achievement in my civil law", Napoleon I

- contained numbers of the parcels of land (or just land), land usage, names etc., and value of the land

- 100 million parcels of land, triangle survey, measurable survey, map scale: 1:2500 and 1:1250

- spread fast around Europe, but faced problems especially in Mediterranean countries, Balkan, and Eastern Europe due to cadastre upkeep costs and troubles.

A cadastre loses its value if register and maps are not constantly updated.

Large-scale surveys are a necessary pre-requisite to map-making. In the late 1780s, a team from the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain, originally under General William Roy began the Principal Triangulation of Britain using the specially built Ramsden theodolite.

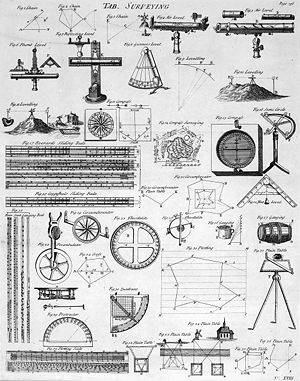

Surveying techniques

Historically, distances were measured using a variety of means, such as chains with links of a known length, for instance a Gunter's chain or measuring tapes made of steel or invar. In order to measure horizontal distances, these chains or tapes would be pulled taut according to temperature, to reduce sagging and slack. Additionally, attempts to hold the measuring instrument level would be made. In instances of measuring up a slope, the surveyor might have to "break" (break chain) the measurement- that is, raise the rear part of the tape upward, plumb from where the last measurement ended.

Historically, horizontal angles were measured using a compass, which would provide a magnetic bearing, from which deflections could be measured. This type of instrument was later improved upon, through more carefully scribed discs providing better angular resolution, as well as through mounting telescopes with reticles for more precise sighting atop the disc (see theodolite). Additionally, levels and calibrated circles allowing measurement of vertical angles were added, along with verniers for measurement down to a fraction of a degree- such as a turn-of-the-century transit.

The simplest method for measuring height is with an altimeter — basically a barometer — using air pressure as an indication of height. But for surveying more precision is needed. Toward this end, a variety of means, such as precise levels, have been developed. Levels are calibrated to provide a precise plane from which differentials in height between the instrument and the point in question can be measured, typically through the use of a vertical measuring rod.

With the triangulation method, one first needs to know the horizontal distance to the object. If this is not known or cannot be measured directly, it is determined as explained in the triangulation article. Then the height of an object can be determined by measuring the angle between the horizontal plane and the line through that point at a known distance and the top of the object. In order to determine the height of a mountain, one should do this from sea level (the plane of reference), but here the distances can be too great and the mountain may not be visible. So it is done in steps, first determining the position of one point, then moving to that point and doing a relative measurement, and so on until the mountaintop is reached.

Surveying Equipment

As late as the 1990s the basic tools used in planar surveying were a tape measure for determining shorter distances, a level for determine height or elevation differences, and a theodolite, set on a tripod, with which one can measure angles (horizontal and vertical), combined with triangulation. Starting from a position with known location and elevation, the distance and angles to the unknown point are measured. A more modern instrument is a total station, which is a theodolite with an electronic distance measurement device (EDM) and can also be used for leveling when set to the horizontal plane. Since their introduction, total stations have made the technological shift from being optical-mechanical devices to being fully electronic with an onboard computer and software. Modern top-of-the-line total stations no longer require a reflector or prism (used to return the light pulses used for distancing) to return distance measurements, are fully robotic, and can even e-mail point data to the office computer and connect to satellite positioning systems, such as a Global Positioning System (GPS). Though real-time kinematic GPS systems have increased the speed of surveying, they are still only horizontally accurate to about 20 mm and vertically accurate to about 30-40 mm.[3] However, GPS systems do not work well in areas with dense tree cover or constructions. Total stations are still used widely, along with other types of surveying instruments. One-person robotic-guided total stations allow surveyors to gather precise measurements without extra workers to look through and turn the telescope or record data. A faster way to measure large areas (not details, and no obstacles) is with a helicopter, equipped with a laser scanner, combined with a GPS to determine the position and elevation of the helicopter. To increase precision, beacons are placed on the ground (about 20 km apart). This method reaches precisions between 5-40 cm (depending on flight height).[4]

Types of surveys and applicability

- ALTA/ACSM Survey: a surveying standard jointly proposed by the American Land Title Association and the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping that incorporates elements of the boundary survey, mortgage survey, and topographic survey. ALTA/ACSM surveys, frequently shortened to ALTA surveys, are often required for real estate transactions.

- Archaeological survey: used to accurately assess the relationship of archaeological sites in a landscape or to accurately record finds on an archaeological site.

- As-Built Survey: a survey conducted several times during a construction project to verify, for local and state boards (USA), that the work authorized was completed to the specifications set on the Plot Plan or Site Plan. This usually entails a complete survey of the site to confirm that the structures, utilities, and roadways proposed were built in the proper locations authorized in the Plot Plan or Site Plan. As-builts are usually done 2-3 times during the building of a house; once after the foundation has been poured; once after the walls are put up; and at the completion of construction.

- Bathymetric Survey: a survey carried out to map the seabed profile.

- Boundary Survey: a survey to establish the boundaries of a parcel using its legal description which typically involves the setting or restoration of monuments or markers at the corners or along the lines of the parcel, often in the form of iron rods, pipes, or concrete monuments in the ground, or nails set in concrete or asphalt. In the past, wooden posts, blazes in trees, piled stone corners or other types of monuments have also been used. A map or plat is then drafted from the field data to provide a representation of the parcel surveyed.

- Construction surveying (otherwise "lay-out" or "setting-out"): the process of establishing and marking the position and detailed layout of new structures such as roads or buildings for subsequent construction. Surveying is regarded as a sub-discipline of civil engineering all over the world. All Degree and Diploma level Engineering institutions ,world wide, have detailed items of Surveying in the curriculum for undergraduate courses in the discipline of Civil Engineering.

- Deformation Survey: a survey to determine if a structure or object is changing shape or moving. The three-dimensional positions of specific points on an object are determined, a period of time is allowed to pass, these positions are then re-measured and calculated, and a comparison between the two sets of positions is made.

- Engineering Surveys: those surveys associated with the engineering design (topographic, layout and as-built) often requiring geodetic computations beyond normal civil engineering practise.

- Erosion and Sediment Control Plan: a plan that is drawn in conjunction with a Subdivision Plan that denotes how upcoming construction activities will effect the movement of stormwater and sediment across the construction site and onto abutting properties and how developers will adjust grading activities to limit the depositing of more stormwater and sediment onto abutting properties than was done prior to construction.

- Foundation Survey: a survey done to collect the positional data on a foundation that has been poured and is cured. This is done to ensure that the foundation was constructed in the location authorized in the Plot Plan, Site Plan, or Subdivision Plan. When the location of the finished foundation is checked and approved the building of the remainder of the structure can commence. This should not be confused with an As-Built Survey which is not to be done until all work on the site is completed.

- Geological Survey: generic term for a survey conducted for the purpose of recording the geologically significant features of the area under investigation. In the past, in remote areas, there was often no base topographic map available, so the geologist also needed to be a competent surveyor to produce a map of the terrain, on which the geological information could then be draped. More recently, satellite imagery or aerial photography is used as a base, where no published map exists. Such a survey may also be highly specialist - for instance focussing primarily on hydrogeological, geochemical or geomagnetic themes. (Do not confuse this term with Geological Survey, typically a government (national, regional or local) body, charged with maintaining and improving the record of the geology of the area in which it operates).

- Hydrographic Survey: a survey conducted with the purpose of mapping the coastline and seabed for navigation, engineering, or resource management purposes. Products of such surveys are nautical charts. See hydrography.

- Mortgage Survey or Physical Survey: a simple survey that generally determines land boundaries and building locations. Mortgage surveys are required by title companies and lending institutions when they provide financing to show that there are no structures encroaching on the property and that the position of structures is generally within zoning and building code requirements. Some jurisdictions allow mortgage surveys to be done to a lesser standard, however most modern U.S. state minimum standards require the same standard of care for mortgage surveys as any other survey. The resulting higher price for mortgage surveys has led some lending institutions to accept "Mortgage Inspections" not signed or sealed by a surveyor.

- Plot Plan or Site Plan: a proposal plan for a construction site that include all existing and proposed conditions on a given site. The existing and proposed conditions always include structures, utilities, roadways, topography, and wetlands delineation and location if necessary. The plan might also, but not always, include hydrology, drainage flows, endangered species habitat, FEMA Federal Flood Insurance Reference Maps and traffic patterns.

- Soil survey, or soil mapping, is the process of determining the soil types or other properties of the soil cover over a landscape, and mapping them for others to understand and use.

- Subdivision Plan: a plot or map based on a survey of a parcel of land. Boundary lines are drawn inside the larger parcel to indicated the creation of new boundary lines and roads . The number and location of plats, or the newly created parcels, are usually discussed back and forth between the developer and the surveyor until they are agreed upon. At this point monuments, usually in the form of square concrete blocks or iron rods or pins, are driven into the ground to mark the lot corners and curve ends, and the plat is recorded in the cadastre (USA, elsewhere) or land registry (UK). In some jurisdictions, the recording or filing of a subdivision plat is highly regulated. The final map or plat becomes, in effect, a contract between the developer and the city or county, determining what can be built on the property and under what conditions. Always upon finally completion of a subdivision an As-Built Plan is required by the local government. This is done so that the roadway constructed therein will pass ownership from the developer to said local government by way of a contract called a Covenant. When this stage is completed the roadways will now be maintained, repaved, swept, and plowed (if necessary for your geographic region) by the local government

- Tape Survey: this type of survey is the most basic and inexpensive type of land survey. Popular in the middle part of the 20th century, tape surveys while being accurate for distance lack substantially in their accuracy of measuring angle and bearing. Considering that a survey is the documentation of one-half (1/2) distances and one-half (1/2) bearings this type of survey is no longer accepted amongst local, state, or federal regulatory committees for any substantial construction work. However for determining the extent of your property boundaries and for your peace-of-mind this type of survey is the least expensive, least time consuming and least invasive, while being nowhere close to accurate for the standards that are practised by professional land surveyors.

- Topographic Survey: a survey that measures the elevation of points on a particular piece of land, and presents them as contour lines on a plot.

- Wetlands Delineation & Location Survey: a survey that is completed when construction work is to be done on or near a site containing defined wetlands. Depending on your local, state, or federal regulations wetlands are usually classified as areas that are completely inundated with water more than two (2) weeks during the growing season. (For USA only) Contact your local or state Conservation Commission or Wetlands Regulatory Commission to determine the particular definition for wetlands in your given geographical region. The boundary of the wetlands is determined by observing the soil colors, vegetation, erosion patterns or scour marks, hydrology, and morphology. Typically blue or pink colored flags are then placed in key locations to denote the boundary of the wetlands. A survey is done to collect the data on the locations of the placed flags and a plan is drawn to reference the boundary of the wetlands against the boundary of the surrounding plots or parcels of land and the construction work proposed within.

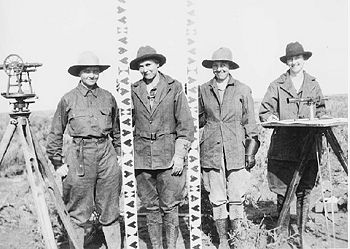

Surveying as a career

The basic principles of surveying have changed little over the ages, but the tools used by surveyors have evolved tremendously. Engineering, especially civil engineering, depends heavily on surveyors. Whenever there are roads, Railways, Reservoir, dams, retaining walls, bridges or Residential areas to be built, surveyors are involved. They establish the boundaries of legal descriptions and the boundaries of various lines of political divisions. They also provide advice and data for geographical information systems (GIS), computer databases that contain data on land features and boundaries.

Surveyors must have a thorough knowledge of algebra, basic calculus, geometry, and trigonometry. They must also know the laws that deal with surveys, property, and contracts. In addition, they must be able to use delicate instruments with accuracy and precision. In the United States, surveyors and civil engineers use units of feet wherein a survey foot is broken down into 10ths and 100ths. Many deed descriptions requiring distance calls are often expressed using these units (125.25 ft). On the subject of accuracy, surveyors are often held to a standard of one one-hundredth of a foot; about 1/8th inch. Calculation and mapping tolerances are much smaller wherein achieving near perfect closures are desired. Though tolerances such as this will vary from project to project, in the field and day to day usage beyond a 100th of a foot is often impractical. In most states of the U.S., surveying is recognized as a distinct profession apart from engineering. Licensing requirements vary by state, however these requirements generally all have a component of education, experience and examinations. In the past, experience gained through an apprenticeship, together with passing a series of state-administered examinations, was required to attain licensure. Nowadays, most states insist upon basic qualification of a Degree in Surveying in addition to experience and examination requirements. Typically the process for registration follows two phases. First, upon graduation, the candidate may be eligible to sit for the Fundamentals of Land Surveying exam, to be certified upon passing and meeting all other requirements as a Surveyor In Training (SIT). Upon being certified as an SIT, the candidate then needs to gain additional experience until he or she becomes eligible for the second phase, which typically consists of the Principles and Practice of Land Surveying exam along with a state-specific examination.

Registered surveyors usually denote themselves with the letters P.S. (professional surveyor), L.S. (land surveyor), or P.L.S. (professional land surveyor), or R.L.S. (registered land surveyor), R.P.L.S. (Registered Professional Land Surveyor), or P.S.M. (professional surveyor and mapper) following their names, depending upon the dictates of their particular state of registration.

In Canada Land Surveyors are registered to work in their respective province. The designation for a Land Surveyor breaks down by province but follows the rule whereby the first letter indicates the province followed by L.S. There is also a designation as a C.L.S. or Canada Lands Surveyor who has the authority to work on Canada Lands which include Indian Reserves, National Parks, the three territories and offshore lands.

In many Commonwealth countries, the term Chartered Land Surveyor is used for someone holding a professional license to conduct surveys.

Typically a licensed land surveyor is required to sign and seal all plans, the format of which is dictated by their state jurisdiction, which shows their name and registration number. In many states, when setting boundary corners land surveyors are also required to place monuments bearing their registration numbers, typically in the form of capped iron rods, concrete monuments, or nails with washers.

Building surveying

Building Surveying emerged in the 1970s as a profession in the United Kingdom by a group of technically minded General Practice Surveyors.[1] Building Surveying is a recognized profession within Britain and Australia. In Australia in particular, due to risk migigation/limitation factors the employment of surveyors at all levels of the construction industry is widespread. There are still many countries where it is not widely recognized as a profession. The Services that Building Surveyors undertake are broad but include:

- Construction design and building works

- Project Management and monitoring

- CDM Co-ordinator under the Construction (Design & Management) Regulations 2007

- Property Legislation adviser

- Insurance assessment and claims assistance

- Defect investigation and maintenance adviser

- Building Surveys and measured surveys

- Handling Planning applications

- Building Inspection to ensure compliance with building regulations

- Undertaking pre-acquisition surveys

- Negotiating dilapidations claims [2]

Building Surveyors also advise on many aspects of construction including:

- design

- maintenance

- repair

- refurbishment

- restoration [3]

Clients of a building surveyor can be the public sector, Local Authorities, Government Departments as well as private sector organisations and work closely with architects, planners, homeowners and tenants groups. Building Surveyors may also be called to act as an expert witness. It is usual for building surveyors to undertake an accredited degree qualification before undertaking structured training to become a member of a professional organisation. Professional organisations for building surveyors include CIOB, ABE, HKIS and RICS.

Quantity surveying

Quantity Surveyors play a key role in the organisation and financial management of construction projects. In essence they manage projects to ensure that they are built on time and to budget. Their job is to manage costs effectively and to ensure that they get the best value from contractors and suppliers. This involves obtaining tenders, arranging contracts and managing costs for the client while the works are undertaken. It is also their job to negotiate with the client's representative on payments and the final settlement. Quantity Surveyors deal with other professionals within their company as well as clients out-side the organisation.

It is an extremely diverse area and can include project management, facility management, construction management and management consultancy.

Land surveyor

Cadastral land surveyors are licensed by State governments. In the United States, cadastral surveys are typically conducted by the Federal government, specifically through the Cadastral Surveys branch of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), formerly the General Land Office (GLO). In the states that have been subdivided as per the Public Land Survey System (PLSS), the BLM Cadastral Surveys are carried out in accordance with said system. This information is required to define ownership and rights in real property (land, water, mineral, easements, rights-of-way, etc.), to resolve boundary disputes between neighbours, and for any subdivision of land, building development, road boundary realignment, etc.

The aim of cadastral surveys is normally to re-establish and mark the corners of original land boundaries. The first stage is to research relevant records such as land titles (deeds), easements, survey monumentation (marks on the ground) and any public or private records that provide relevant data.

Monuments are marks on the ground that define location. Pegs are commonly used to mark boundary corners, and nails in bitumen, small pegs in the ground (dumpys) and steel rods are used as instrument locations and reference marks, commonly called survey control. Marks should be durable and long lasting, stable so the marks do not move over time, safe from disturbance and safe to work at. The aim is to provide sufficient marks so some marks will remain for future re-establishment of boundaries. The job of a boundary surveyor retracing a deed or prior survey is to locate such monuments and verify their correct position. Unfortunately time, development, vandalism and acts of nature often wreak havoc on monuments. The boundary surveyor is often forced to consider evidence peripheral to an actual marker, which may be missing. Fence locations, woodlines, monuments on neighboring property, parole evidence and other evidence is often analyzed. Examples of typical man made monuments are steel rods, pipes or bars with plastic, aluminum or brass caps containing descriptive markings and often bearing the license number of the surveyor responsible for the establishment of such. The material and marking used on monuments placed to mark boundary corners are often subject to state laws/statutes.

The total station or GPS is set-up over survey marks which were placed as part of a previous survey, or newly placed marks. The bearing datum is established by measuring between points on a previous survey and a rotation is applied to orientate the new survey to correspond with the previous survey.

The data is analysed and comparisons made with existing records to determine evidence which can be used to establish boundary positions. The bearing and distance of lines between the boundary corners and total station positions are calculated and used to set out and mark the corners in the field. Checks are made by measuring directly between pegs places using a cloth tape. Subdivision of land generally requires that the external boundary is re-established and marked using pegs, and the new internal boundaries are then marked.

A plat (survey plan) and description (depending on local and state requirements) are compiled, the final report is lodged with the appropriate government office (often required by law), and copies are provided to the client.

The Art of Surveying While one might assume that the manipulation of property and numbers might be devoid of art, only the contrary can be true. Many properties have considerable problems with regards to improper bounding, miscalculations in past surveys, titles, easements, and wildlife crossings. Also many properties are created from multiple divisions of a larger piece over the course of years, and with every additional division the risk of miscalculation increases. The result can be abutting properties not coinciding with adjacent parcels, resulting in hiatuses (gaps) and overlaps. The art comes in when a surveyor must essentially build a puzzle with pieces that do not exactly fit together. In these cases the solution is based upon the research and interpretation of the surveyor, and following established procedures for resolving discrepancies.

References

- ↑ Johnson, Anthony, Solving Stonehenge: The New Key to an Ancient Enigma. (Thames & Hudson, 2008) ISBN 978-0-500-05155-9

- ↑ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), "Engineering", pp. 766-9, in Rashed, Roshdi & Régis Morelon (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Routledge, 751-795, ISBN 0415124107

- ↑ National Cooperative Highway Research Program: Collecting, Processing and Integrating GPS data into GIS, p. 40. Published by Transportation Research Board, 2002 ISBN 0309069165, 9780309069168

- ↑ Toni Schenk1, Suyoung Seo, Beata Csatho: Accuracy Study of Airborne Laser Scanning Data with Photogrammetry, p. 118

- Keay J (2000), The Great Arc: the dramatic tale of how India was mapped and Everest was named, Harper Collins, 182pp, ISBN 0-00-653123-7.

- Pugh J C (1975), Surveying for Field Scientists, Methuen, 230pp, ISBN 0-416-07530-4

- Genovese I (2005), Definitions of Surveying and Associated Terms, ACSM, 314pp, ISBN 0-9765991-0-4.

External links

-

- Old versus new — how a new surveying technology can create instant CAD models — A web article

- As-builts – Problems & Proposed Solutions — Discussion on Building Surveys within Construction industry by Stephen R. Pettee, CCM