Supermarine Spitfire

| Spitfire | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The distinctive silhouette of a typical Spitfire shows elliptical wings. (P7350, a Mk IIa, was first delivered to 266 Squadron on 6 September 1940.) | |

| Role | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | Supermarine |

| Designed by | R. J. Mitchell |

| First flight | 6 March 1936[1] |

| Introduction | 4 August 1938[1] |

| Retired | 1955, RAF |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 1938–1948 |

| Number built | 20,351[2] |

| Unit cost | £12,604 (1939)[3] |

| Variants | Seafire Spiteful |

The Supermarine Spitfire was a British single-seat fighter aircraft, used by the Royal Air Force and many other Allied countries during the Second World War, and into the 1950s. It was produced in greater numbers than any other Allied design. The Spitfire was the only Allied fighter in production at the outbreak of the Second World War that was still in production at the end of the war.

The Spitfire was designed by R. J. Mitchell who was chief designer at Supermarine Aviation Works, a subsidiary of Vickers-Armstrongs. He continued to refine the design until his death from cancer in 1937, whereupon his colleague Joseph Smith became chief designer.[4] Its elliptical wing had a thin cross-section, allowing a higher top speed than the Hawker Hurricane and many other contemporary designs.

The distinctive silhouette imparted by the wing planform helped the Spitfire to achieve legendary status during the Battle of Britain. There was, and still is, a public perception that it was the RAF fighter of the Battle, in spite of the fact that the more numerous Hurricane shouldered a great deal of the burden against the potent Luftwaffe. Much loved by its pilots, the Spitfire saw service throughout the whole of the Second World War, in most theatres of war, in several roles and in many different variants. The Spitfire was to continue to serve as a front line fighter and in secondary roles for several air forces well into the 1950s.

The Spitfire will always be compared to its main adversary, the Messerschmitt Bf 109: both were among the finest fighters of their day and followed similar design philosophies of marrying a small, streamlined airframe to a powerful liquid-cooled V12 engine.

Contents |

Design and development

R. J. Mitchell's 1931 design to meet Air Ministry specification F7/30 for a new and modern fighter capable of 250 mph, the Supermarine Type 224, resulted in an open-cockpit monoplane with bulky gull-wings and a large fixed, spatted undercarriage powered by the 600 horsepower evaporative-cooled Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine.[5] This made its first flight in February 1934.[6][7] This aircraft was a big disappointment to Mitchell and his design team, who immediately embarked on a series of "cleaned up" designs, using their experience with the Schneider trophy seaplanes as a starting point. The F7/30 design accepted was the biplane Gloster Gladiator.[8]

Mitchell had already begun working on a new aircraft, designated Type 300, based on the Type 224. With a retractable gear and 6 ft shorter wingspan, the aircraft was submitted to the Air Ministry in July 1934, but again was not accepted.[9] The design evolved through a number of changes, including an enclosed cockpit, oxygen breathing-apparatus, even smaller and thinner wings, and the newly-developed and much more powerful Rolls-Royce PV-XII Vee-12 engine, later named the Merlin. In November 1934, Mitchell, with the backing of Supermarine's owner, Vickers-Armstrongs, started detailed design work on the Type 300.[10] The Air Ministry issued a contract AM 361140/34 on 1 December 1934, providing £10,000 for the construction of Mitchell's "improved F.7/30 design".[11] On 3 January 1935, the Air Ministry formalised the contract and a new Specification F.10/35 was written around the aircraft.[12]

Just 15 months later, after several major design changes and refinements, on 5 March 1936[13] [a] the sleek new prototype (K5054) took off on its first flight from Eastleigh Aerodrome (later Southampton Airport). At the controls was Captain J. "Mutt" Summers, (Chief Test Pilot for Vickers (Aviation) Ltd.), who was reported in the press as saying "Don't touch anything" on landing.[14] This flight was just four months after the maiden flight of the contemporary Hawker Hurricane.[15]

Testing continued until 26 May 1936, when Summers flew K5054 to RAF Martlesham Heath and handed the aircraft over to Squadron Leader Anderson of the Aeroplane & Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE).

The Air Ministry placed an order for 310 aircraft on 3 June 1936,[16] before any formal report had been issued by the A&AEE, interim reports being issued on a piecemeal basis. The British public first saw the Spitfire at the RAF Hendon air-display on Saturday 27 June 1936. Although full-scale production was supposed to begin immediately, there were numerous problems which could not be overcome for some time and the first production Spitfire K9787 didn't roll off the Woolston, Southampton assembly line until mid-1938. [1] The first and most immediate problem was that the main Supermarine factory at Woolston was already working at full capacity fulfilling orders for Walruses and Stranraers. Although outside contractors were supposed to be involved in manufacturing many important Spitfire components, especially the wings, Vickers-Armstrongs (the parent company) were extremely reluctant to see the Spitfire being manufactured by outside concerns and were slow to release the necessary blueprints and sub-components. As a result of the innumerable delays in getting the Spitfire into full production, the Air Ministry put forward a plan that production of the Spitfire be stopped after the initial order for 310, after which Supermarine would build Bristol Beaufighters. The managements of Supermarine and Vickers were able to persuade the Air Ministry that the problems could be overcome and further orders were placed for 200 Spitfires on 24 March 1938 (the two orders covered the K, L and N prefix serial numbers).[17]

Name origin

The Air Ministry submitted a list of possible names to Vickers-Armstrongs for the new aircraft, now known as the Type 300. One of these was the improbable Shrew. The name Spitfire was suggested by Sir Robert MacLean, director of Vickers-Armstrongs at the time, who called his daughter Ann "a little spitfire."

The word dates from Elizabethan times and refers to a particularly fiery, ferocious type of person.[18] The name had previously been used unofficially for Mitchell's earlier F.7/30 Type 224 design. Mitchell is reported to have said that it was "just the sort of bloody silly name they would choose",[19].

Airframe

In the mid-1930s, aviation design teams worldwide started developing a new generation of all-metal, low wing fighter aircraft. Aircraft such as the French Dewoitine D.520, and Germany's Messerschmitt Bf 109 were designed to take advantage of new techniques of monocoque construction, and new high-powered, liquid-cooled, in-line aero engines. They also featured refinements such as retractable undercarriages, fully enclosed cockpits and low drag, all metal wings (all introduced on civil airliners years before, but slow to be adopted by the military who favoured the simplicity and manoeuvrability of the biplane).

Mitchell's design aims were to create a well balanced high performance fighter aircraft which would be able to fully utilise the power of the Merlin engine and, at the same time would be relatively easy to fly. To that end his design team developed an airframe which, for its day, was complex.

The exceptionally well streamlined semi-monocoque duralumin fuselage featured a large number of compound curves and was built up from a skeleton of 19 frames, starting from the main engine bulkhead, or frame number one. Aft of the engine bulkhead were five half frames to accommodate the fuel tanks and cockpit. From the seventh, which was the frame to which the pilot's seat and (later) armour plating was attached, to the 15th, which was mounted at a forward angle just forward of the tailfin, the frames were oval in shape, each reducing slightly in size, and had numerous holes drilled through them to lighten the structural weight as much as possible without weakening them. Frame 16 formed a double bulkhead with frame 17, which was extended to form the main spar of the vertical fin; frame 18 formed the secondary spar. Just aft of this the 19th frame formed the rudder post. A combination of 14 longitudinal stringers and two main longerons helped form a light but rigid structure to which sheets of alclad stressed skinning were attached. There was plenty of room to later fit camera equipment and fuel tanks.[20][21]

The skin of the fuselage, wings and tailplane was attached with rivets, and in critical areas, such as the wing forward of the main spar where an uninterrupted airflow was required, flush rivets were used. In some areas, such as the rear of the wing, the top was riveted and the bottom fixed by woodscrews into sections of spruce; later pop-riveting would be used for these areas.[22] From 1943 on, flush riveting was used throughout the entire airframe; the first version of the Spitfire to change to flush riveting was the Mk XII closely followed by all Castle Bromwich built Mk IXs.[23] At first the ailerons, elevators and rudder were fabric covered. However, once combat experience showed that the fabric covered ailerons became impossible to use at high speeds the fabric was replaced with a light-alloy, enhancing control throughout the speed range.

Elliptical wing design

From early on Mitchell and the design staff were contemplating an elliptical wing shape to solve the conflicting requirements of having the lowest possible thickness-to-chord ratio to reduce drag, and having room to install a retractable undercarriage, as well as the projected armament and ammunition which, in April 1935, was changed from two .303 Vickers machine guns in each wing to four .303 Brownings.[24]

It has been suggested that Mitchell copied the wing shape of the Heinkel He 70. Mitchell's aerodynamicist, Beverley Shenstone, however, has pointed out that the He 70 was designed to fulfil a completely different role and that other aircraft also had elliptical wings. The Spitfire wing was much thinner with a completely different section.[25] As a practical engineer Mitchell was fully aware of the efficiency of the elliptical wing, as were Siegfried and Walter Günther, who designed the Heinkel.[b]

A design aspect of the wing which contributed greatly to its success was an innovative spar boom design, made up of five square concentric tubes which fitted into each other. Two of these booms were linked together by an alloy web creating a lightweight and very strong main spar. The undercarriage legs were attached to pivot points built into the inner, rear of the main spar and retracted outwards and slightly backwards into wells in the non-load carrying wing structure. The narrow undercarriage track was considered to be an acceptable compromise as it allowed the landing impact loads to be transmitted to the strongest parts of the wing structure.

Ahead of the spar, the thick-skinned leading edge of the wing formed a strong and very rigid D-shaped box, which took most of the wing loads. At the time the wing was designed this D-shaped leading edge was intended to house steam condensers for the evaporative cooling system intended for the PV XII. The constant problems with the evaporative system in the Goshawk led to the adoption of a 100% glycol cooling system,[c] together with a new radiator duct design, devised by a Fredrick Meredith of the RAE at Farnborough, which used to cooling air to generate thrust, greatly reducing the drag produced by the radiators.[26] This meant that the leading edge structure lost its function as an evaporator, but it was later to become very useful as it was able to be adapted to house integral fuel tanks of various sizes.[27]

The wing section used was a NACA 2200 series which had been adapted to create a thickness to chord ratio of 13% at the root reducing to 6% at the tip.[28] A dihedral of six degrees was adopted to give increased lateral stability.

Another feature of the wing was its washout. The trailing edge of the wing twisted slightly upward along its span, the angle of incidence decreased from +2 degrees at its root to -1/2 degree at its tip.[28] This caused the wing roots to stall before the tips, reducing tip stall that may have resulted in a spin. This washout was first featured in the wing of the Type 224 and became a consistent feature in subsequent designs leading to the Spitfire.[29]

If the stick was pulled back too far on the Spitfire in a tight turn, the aircraft could stall rather violently, flick over on to its back, and spin. Knowledge of this undoubtedly deterred Spitfire pilots from tightening their turns when being chased, particularly if they were inexperienced.[30]

At first the complexity of the wing design, especially the precision required to manufacture the vital spar and leading edge structures, caused some major hold-ups in the production of the Spitfire. This was amplified when the work was put out to sub-contractors, most of whom had never dealt with metal-structured, high-speed aircraft. Over time, however, these problems were overcome and thousands of these wings, of six basic types, were built.[27]

One flaw in the thin-wing design of the Spitfire manifested itself when the aircraft was brought up to very high speeds. When the pilot attempted to roll the aircraft at these speeds, the aerodynamic forces on the ailerons were enough to twist the entire wingtip in the direction opposite of the aileron deflection (much like the way an aileron trim tab will deflect the aileron itself). This so-called aileron reversal resulted in the Spitfire rolling in the opposite direction to the control column input. In March 1943, R.A.E. noted that at 400 mph I.A.S., roughly 65% of aileron power was lost due to wing twist.[31] The new wing of the Spitfire F Mk 21 and its successors was designed to help alleviate this problem.[d] [32][33]

The ellipse also served as the design basis for the Spitfire’s fin and tailplane assembly, once again exploiting the shape’s favourable aerodynamic characteristics. Both the elevators and rudder were shaped so that their centre of mass was shifted forward thus reducing control surface flutter. The longer noses and greater propeller wash resulting from larger engines in later models necessitated increasingly larger vertical and, later, horizontal tail surfaces to compensate for the altered aerodynamics, culminating in those of the Mk 22/24 series which were 25% larger in area than those of the Mk I.[34][35]

Carburettor versus fuel injection

Early in its development, the Merlin engine's lack of direct fuel injection meant that both Spitfires and Hurricanes, unlike the Bf 109E, were unable to simply nose down into a steep dive. This meant a Luftwaffe fighter could simply "bunt" into a high-power dive to escape an attack, leaving the Spitfire sputtering behind, as its fuel was forced by negative "g" out of the carburettor. RAF fighter pilots soon learned to "half-roll" their aircraft before diving to pursue their opponents. The use of carburettors was calculated to give a higher specific power output, due to the lower temperature, and hence the greater density, of the fuel/air mixture fed into the motor, compared to injected systems. In March 1941, a metal diaphragm with a hole in it was fitted across the float chambers. It partly cured the problem of fuel starvation in a dive, and became known as "Miss Shilling's orifice" as it was invented by a female engineer, Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling. Further improvements were introduced throughout the Merlin series, with Bendix-manufactured pressure carburettors introduced in 1943.

Production

In February 1936 the Vickers-Armstrongs director, Sir Robert MacLean, guaranteed production of 5 aircraft a week, beginning 15 months after an order is placed. On 3 June 1936, the Air Ministry placed an order for 310 aircraft, for a price of £1,395,000.[36] Full-scale production of the Spitfire began at Supermarine's facility in Woolston, Southampton, but it quickly became clear that the order could not be completed in the 15 months promised. Supermarine was a small company, already busy building the Walrus and Stranraer, and its parent company, Vickers, was busy building the Wellington. The initial solution was to subcontract the work out.[36]The first production Spitfire rolled off the assembly line in mid-1938, [1] and was flown on 15 May 1938, almost 24 months after the initial order.[37] The final cost of the first 310 aircraft, after delays and increased programme costs, came to ₤1,870,242 or ₤1,533 more per aircraft than originally estimated.[38]

Castle Bromwich

With war becoming increasingly inevitable, and to help build the Spitfires in the numbers anticipated, a huge new facility was started on 12 July 1938 at Castle Bromwich, near Birmingham, as a "shadow" to Supermarine's original factories in Southampton: the most modern machine tools then available were being installed two months after work started on the site.[38] Although the project was at first managed and equipped by Morris Motors Ltd under Lord Nuffield, who was an expert in mass construction in the motor-vehicle industry, it was funded by government money. However, although the new factory had been completed in late 1939, continual problems were experienced in building a complete airframe. The Spitfire's stressed-skin construction required skills and techniques outside the experience of the local labour force and a continual stream of changes were demanded by the RAF. Finally, on 17 May 1940, with no sign of a single Spitfire being built, Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Aircraft Production, outmanoeuvred Lord Nuffield and took over Castle Bromwich for the government.[39] Beaverbrook immediately sent in experienced management staff and experienced workers from Supermarine and Vickers-Armstrongs. In June 1940, 10 Mk IIs were built,[40] in July, 23 rolled out, in August they produced 37, and in September the count was 56.[41] These were the first of thousands of Spitfires to emerge from Castle Bromwich.

Production dispersal

The Germans were fully aware of the importance of the Spitfire and during the Battle of Britain concerted efforts were made by the Luftwaffe to destroy the main manufacturing plants at Woolston and Itchen, near Southampton. The first raid, which missed the factories, came on 23 August 1940. Over the next month other raids were mounted until on 26 September 1940, both factories were completely wrecked,[42] with 92 people being killed and a large number injured: most of the casualties were experienced aircraft production workers.[43][44]

Fortunately for the future of the Spitfire many of the production jigs and machine tools had already been relocated by 20 September and steps were being taken to disperse production to small facilities throughout the Southampton area.[42] To this end the British government requisitioned the likes of Vincent's Garage in Station Square Reading, which later specialised in manufacturing Spitfire fuselages, and Anna Valley Motors, Salisbury which was to become the sole producer of the wing leading-edge fuel tanks for photo reconnaissance Spitfires, as well as producing other components. A purpose built works, specialising in manufacturing fuselages and installing engines, was built at Star Road, Caversham in Reading. The drawing office, in which all Spitfire designs were drafted was relocated to another purpose built site at Hursley Park, near Southampton. This site also had an aircraft assembly hangar, with its associated aerodrome, where many of the prototype and experimental Spitfires were assembled and flown.[43]

Four towns and their satellite airfields were chosen to be the focal points for these workshops. They were:[42]

- Southampton and Eastleigh Airport

- Salisbury with High Post and Chattis Hill aerodromes[e] [45]

- Trowbridge with Keevil aerodrome

- Reading with Henley and Aldermaston aerodromes.

Completed Spitfires were delivered to the airfields on large Commer "Queen Mary" low-loader articulated trucks, there to be fully assembled, tested, then passed on to the RAF.[43]

Flight testing

One of the factors in the success of the Spitfire is that every single one built was flight tested before delivery. During the Second World War Jeffrey Quill was Vickers Supermarine's chief test pilot; he oversaw a group of 10 to 12 pilots[f]responsible for testing all developmental and production Spitfires built by the company in the Southampton area. Jeffrey Quill devised the standard testing procedures, which, with some variations for the numerous variants, operated from 1938, and was in charge of all flight testing of all aircraft types built by Vickers Supermarine.[46][47] Alex Henshaw, Chief Test Pilot at Castle Bromwich from 1940, was placed in charge of testing all Spitfires built at that factory, coordinating a team of 25 pilots, and also assessing Spitfire developments. Between 1940 and 1946 Henshaw flew a total of 2,360 Spitfires and Seafires, more than 10% of total production.[48][49]

Henshaw wrote about flight testing Spitfires

After a thorough pre-flight check I would take off and once at circuit height, I would trim the aircraft and try to get her to fly straight and level with hands off the stick...Once the trim was satisfactory I would take the Spitfire up in a full throttle climb at 2,850 rpm to the rated altitude of one or both supercharger blowers. Then I would make a careful check of the power output from the engine, calibrated for height and temperature...If all appeared satisfactory I would then put her into a dive at full power and 3,000 rpm, and trim her to fly hands and feet off at 460 mph IAS (Indicated Air Speed). Personally, I never cleared a Spitfire unless I had carried out a few aerobatic tests to determine how good or bad she was. The production test was usually quite a brisk affair: the initial circuit lasted less than ten minutes and the main flight took between twenty and thirty minutes. Then the aircraft received a final once over by our ground mechanics, any faults were rectified and the Spitfire was ready for collection. I loved the Spitfire in all of her many versions. But I have to admit that the later Marks, although they were faster than the earlier ones, were also much heavier and so did not handle so well. You did not have such positive control over them. One test of manoeuvrability was to throw her into a flick roll and see how many times she rolled. With the Mark II or the Mark V one got two and a half flick rolls but the Mark IX was heavier and you got only one and a half. With the later and still heavier versions one got even less. The essence of aircraft design is compromise, and an improvement at one end of the performance envelope is rarely achieved without a deterioration somewhere else.[50][51]

When the last Spitfire rolled out in February 1948,[52] a total of 20,351 examples of all variants were built, including two-seat trainers, with some Spitfires remaining in service well into the 1950s.[2] The Spitfire was the only British fighter aircraft to be in continual production before, during, and after the Second World War.[53]

Operational history

The operational history of the Spitfire with the RAF started with the first Mk Is, which entered service with 19 Squadron at RAF Duxford on 4 August 1938.[54] The last flight of a Spitfire in RAF service, which took place on 9 June 1957, was by a PR 19, PS583, from RAF Woodvale of the Temperature and Humidity Flight. This was also the last known flight of a piston-engined fighter in the RAF.[55]

The Spitfire achieved legendary status during the Battle of Britain but continued to play increasingly diverse roles throughout World War II and beyond, often in air forces other than the RAF. The Spitfire became the first high-speed photo-reconnaissance aircraft to be operated by the RAF. Sometimes unarmed, they flew at high, medium and low altitudes, often ranging far into enemy territory to closely observe the Axis powers and provide an almost continual flow of valuable intelligence information throughout the war. In 1941 and 1942 PRU Spitfires provided the first photographs of the Freya and Würzburg radar systems and, in 1943, helped confirm that the Germans were building the V1 and V2 Vergeltungswaffe ("vengeance weapons") by photographing Peenemünde, on the Baltic Sea coast of Germany.

In the Mediterranean the Spitfire blunted the heavy attacks on Malta by the Regia Aeronautica and Luftwaffe and, from early 1943, helped pave the way for the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy. Malta was the first location outside of Britain where Spitfires saw service.[56] Over the Northern Territory of Australia RAAF Spitfires helped defend the port city of Darwin against air attack by the Japanese Naval Air Force.

Speed and altitude records

Beginning in late 1943, high-speed diving trials were undertaken at Farnborough to investigate the handling characteristics of aircraft travelling at speeds near the sound barrier (i.e. the onset of compressibility effects). Because it had the highest limiting Mach number of any aircraft at that time, a Spitfire XI was chosen to take part in these trials. Due to the high altitudes necessary for these dives, a fully feathering Rotol propeller was fitted to prevent overspeeding. It was during these trials that EN409, flown by Squadron Leader J. R. Tobin, reached 606 mph (975 km/h, Mach 0.891) in a 45 degree dive. In April 1944 the same aircraft suffered engine failure in another dive while being flown by Squadron Leader A. F. Martindale, when the propeller and reduction gear broke off. Martindale successfully glided the Spitfire 20 miles (32 km) back to the airfield and landed safely.[57]

On 5 February 1952, a Spitfire 19 of No. 81 Squadron RAF based in Hong Kong reached probably the highest altitude ever achieved by a Spitfire. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Ted Powles,[58] was on a routine flight to survey outside air temperature and report on other meteorological conditions at various altitudes in preparation for a proposed new air service through the area. He climbed to 50,000 feet (15,240 m) indicated altitude, with a true altitude of 51,550 feet (15,712 m). The cabin pressure fell below a safe level, and in trying to reduce altitude, he entered an uncontrollable dive which shook the aircraft violently. He eventually regained control somewhere below 3,000 feet (900 m) and landed safely with no discernible damage to his aircraft. Evaluation of the recorded flight data suggested that, in the dive, he achieved a speed of 690 mph (1,110 km/h, Mach 0.94), which would have been the highest speed ever reached by a propeller-driven aircraft.[57]

The critical Mach number of the Spitfire's original elliptical wing was higher than the subsequently-used laminar-flow-section, straight-tapering planform wing of the follow-on Supermarine Spiteful, Seafang and Attacker, illustrating that Reginald Mitchell's thoughtful and practical engineering approach to the problems of high speed flight had paid off handsomely.[59]

Variants

As its designer, R.J. Mitchell will forever be known for his most famous creation. However, the development of the Spitfire did not cease with his premature death in 1937. Mitchell only lived long enough to see the prototype Spitfire fly. Subsequently a team led by his Chief Draughtsman, Joe Smith, would develop more powerful and capable variants to keep the Spitfire current as a front line aircraft. As one historian noted: "If Mitchell was born to design the Spitfire, Joe Smith was born to defend and develop it."[60]

There were 24 marks of Spitfire and many sub-variants. These covered the Spitfire in development from the Merlin to Griffon engines, the high speed photo-reconnaissance variants and the different wing configurations. The Spitfire Mk V was the most common type, with 6,487 built, followed by the 5,656 Mk IX airframes produced.[61] Different wings, featuring a variety of weapons, were fitted to most marks; the A wing used eight .303 machine guns, the B wing with four .303 machine guns and two 20 mm Hispano cannon, and the C or Universal Wing which could mount either four 20 mm cannon or two 20 mm and four .303 machine guns. As the war progressed, the C wing became more common.[62] The final armament variation was the E wing which housed two 20 mm cannon and two .50 inch Browning heavy machine guns.

Supermarine developed a two-seat variant to be used for training and was known as the T Mk VIII, but no orders were received for this aircraft and only one example was ever constructed (identified as N32/G-AIDN by Supermarine).[63] However, in the absence of an official two-seater variant, a number of airframes were crudely converted in the field. These included a 4(SAAF) Squadron Mk VB in North Africa, where a second seat was fitted instead of the upper fuel tank in front of the cockpit, although it was not a dual-control aircraft and is thought to have been used as the squadron "run-about."[64] The only unofficial two-seat conversions that were fitted with dual-controls were a small number of Russian lend/lease Mk IX aircraft. These were referred to as Mk IX UTI and differed from the Supermarine proposals by using an inline "greenhouse" style double canopy rather than the raised "bubble" type of the T Mk VIII.[64]

In the postwar era, the idea was revived by Supermarine and a number of two-seat Spitfires were built by converting old Mk IX airframes with a second "raised" cockpit featuring a bubble canopy. Ten of these TR9 variants were then sold to the Indian Air Force along with six to the Irish Air Corps, three to the Royal Dutch Air Force and one for the Royal Egyptian Air Force[63]. Today, only a handful of the trainers are known to exist, including both the T Mk VIII and a T Mk IX based in the U.S., and the "Grace Spitfire" ML407 – a variant of the Mk IX that is a privately owned (formerly IAC-162) TR9 and operates out of Duxford, UK. The second cockpit of this aircraft has been lowered and is now below the front cockpit. This modification is known as the Grace Canopy Conversion, and was designed by Nick Grace, who rebuilt ML407. IAC-161 (Previously PV202) has also been recently restored to flying condition.

The Seafire, a name arrived at by collapsing the longer Sea Spitfire, was a naval version of the Spitfire specially adapted for operation from aircraft carriers. Although never conceived for the rough-and-tumble of carrier-deck operations, the Spitfire was considered to be the best candidate available at the time and went on to serve with distinction. Modifications included an arrester hook, folding wings and other specialised equipment. Some features of the basic design were, whilst unproblematic for land operation, problematic for carrier deck operations. One was poor visibility over the nose; and like the Spitfire, the Seafire had a relatively narrow undercarriage track which meant that it was not ideally suited to deck operations. The addition of heavy carrier equipment also added to the weight of the machine and reduced low-speed stability, critical for such operations, and normally a forte of the Spitfire. Early marks of Seafire had relatively few modifications, however late marks were heavily-adapted.

The Seafire II was able to outperform the A6M5 Zero at low altitudes when the two types were tested against each other during wartime mock combat exercises. Contemporary Allied carrier fighters such as the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair, however, were considerably more robust and practical for carrier operations. A performance advantage was regained when late-war Seafire marks equipped with the Griffon engines supplanted their Merlin-engined predecessors.

Griffon-engined variants

The first Rolls Royce Griffon-engined Mk XII flew on August 1942, but only five had reached service status by the end of the year. This mark could nudge 400 mph in level flight and climb to an altitude of 24,000 ft (10,000 m) in under nine minutes.[65] Although the Spitfire continued to improve in speed and armament, range and fuel capacity were major issues: it remained "short-legged" throughout its life except in the dedicated photo-reconnaissance role, when its guns were replaced by extra fuel tanks.

Newer Griffon-engined Spitfires were being introduced as home-defence interceptors, where limited range was not an impediment. These faster Spitfires were used to defend against incursions by high-speed "tip-and-run" German fighter-bombers and V-1 flying bombs over Great Britain.

As American fighters took over the long-range escorting of USAAF daylight bombing raids, the Griffon-engined Spitfires progressively took up the tactical air superiority role as interceptors, while the Merlin-engined variants (mainly the Mk IX and the Packard-engined XVI) were adapted to the fighter-bomber role.

Although the later Griffon-engined marks lost some of the favourable handling characteristics of their Merlin-powered predecessors, they could still out-manoeuvre their main German foes and other, later American and British-designed fighters.

Griffon-engined Spitfires and Seafires continued to be flown by many squadrons of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve until re-equipped in 1951–52.

In late 1962, Air Marshal Sir John Nicholls instigated an interesting trial when he flew a Spitfire against the supersonic Lightning F 3 interceptor in mock combat at RAF Binbrook. At the time British Commonwealth forces were involved in possible action against Indonesia over Malaya and Nicholls decided to develop tactics to fight the Indonesian Air Force P-51 Mustang, a fighter that had a similar performance to the Spitfire PR 19.[66] He concluded that the most effective and safest way for a modern jet-engined fighter to attack a piston-engined fighter was from below and behind; contrary to all established fighter-on-fighter doctrine.[67]

Survivors

There are approximately 54 Spitfires and a few Seafires airworthy worldwide, although many air museums have examples on static display. For example, Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry has paired a static Spitfire with a static Ju 87 R-2/Trop. Stuka dive bomber.[68]

- Perhaps the most famous of all Spitfires still flying today is MH434 an MkIXb (genuine combat history with 7 and half confirmed kills), owned and run by The Old Flying Machine Company. This plane was usually flown by Ray Hanna, ex-Red Arrows leader and one of the best display pilots of all time up until his death in late 2005. The plane has been seen and enjoyed by millions of people at European airshows usually in one of the most thrilling displays of the day. It is also a major TV and film star in its own right and was the plane that flew the famous bridge scene in Piece of Cake and has been in many other TV and films including Operation Crossbow, The Battle of Britain and also graces the cover of Jeremy Clarkson's book I Know You Got Soul.

- The RAF Battle of Britain Memorial Flight at RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire maintains and operates five Spitfires (of various marks) for flying display and ceremonial purposes.

- A Spitfire XIVe, MV293 owned by The Fighter Collection at Duxford is marked as MV268, JE-J, flown by Wing Commander Johnnie Johnson OC 127 Wing, Germany May 1945. There are regularly more than a dozen Spitfires on site at Duxford. Whilst some of these are under restoration in a private hangar many flying and static examples can be seen in hangars one to five.

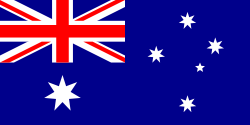

- The Temora Aviation Museum in Temora, New South Wales, Australia, has two airworthy Spitfires: a Mk VIII and a Mk XVI, which are flown regularly during the museum's flying weekends.[69]

- A Supermarine Spitfire LF Mk XVIE is on display in the Polish Aviation Museum.

- The Hellenic Air Force Museum own and displays a Supermarine Spitfire Mk IXc.[70]

- Kennet Aviation, a British company specializing in ex-military aircraft has a Seafire XVII and a number of Seafire projects at its home airfield at North Weald Airfield.[71]

- The Black Spitfire is a black-painted Spitfire which belonged to Israeli pilot and former president Ezer Weizman. It is on exhibit in the Israeli Air Force Museum in Hatserim and is used for ceremonial flying displays.

- Kermit Weeks keeps a restored Mk XVI at his Fantasy of Flight museum in Florida.[72]

- The "TAM Asas de Um Sonho" Museum, located in São Carlos, Brazil, owns the only airworthy Spitfire in South America, a Mk IXc donated to the museum by Rolls Royce and painted in the colours and markings of RAF ace Johnnie Johnson.

- One of the newest Spitfires to fly in Canadian skies is Michael Potter's Supermarine Mk XVI Spitfire SL721/N721WK/C-GVZB, refinished in the markings of No. 421 Squadron RCAF and is now registered in Gatineau, Quebec as part of the Vintage Wings of Canada Collection.

- A Seafire 47, the final aircraft in the long and distinguished line of aircraft, is airworthy with Jim Smith in the U.S. after being restored by Ezell Aviation.

- The Shuttleworth Collection maintains and displays an airworthy Mk Vc, AR501.

- One Spitfire Mk IX is on display at the "Vigna di Valle Museum" (Italian Air Force Museum) Bracciano, Rome, Italy.

- A Spitfire Mark XVI has been displayed at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand, since 1956 when New Zealander Sir Keith Park, commander of No 11 Fighter Group, arranged for it to be donated.

- The Lone Star Flight Museum in Galveston, Texas has a Spitfire Mk XVI TE392/N97RW in flying condition painted in commemoration of Texas Ace, Lance C. Wade who flew with the RAF from December 1940 until his death in Foggia Italy, 1944.

- The RNYFC Ex Vehicles of Her Majesties Forces Storage yard and small Youth Core Group have ten working Spitfire Mark XVI's. These fly from a small ex-RAF training station

- The Kent Spitfire, a MK IX Serial TA805, today flies from the ex-RAF station at Biggin Hill. After the war it was used by the South African Air Force, recovered from a scrap yard, and returned to England in the early 1990s. It wears 234 Squadron markings with coding FX-M.[73]

- TE330, a LF Mk XVIe owned by the Subritzky family of the North Shore, Auckland, New Zealand was sold for NZD$2.8 million in September 2008. [74] TE330 was built at Castle Bromwich in late April 1945 and in 1957 joined the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. It was sold to the Smithsonian Institution in September 1959[g], and was put on display in the USAF museum at Dayton, Ohio in 1961. In 1996 the aircraft was bought by a Hong Kong based businessman, James Slade, who shipped it to Don Subritzky for restoration work in 1997. In 1999 TE330 was sold to the Subritzky family.[75] The airworthy aircraft was bought at the auction in New Zealand by Hong Kong businessman Yan-Ming Gao who intends to donate it to the China Aviation Museum in Beijing.[74]

- Spitfire RW388, Mk XVI Spitfire, is located at the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Hanley, Stoke on Trent. It was formally presented to the City of Stoke-on-Trent in 1972 and was built by the contractor Vickers Armstrong, in Castle Bromwich. The original contract number was B981867/39. It is fitted with a Merlin 266 (Packard) engine.[76]

- The Fighter Factory in Suffolk, Virginia has a 1943 Vickers Supermarine Spitfire Mk IX that flew 15 sorties in Italy and appeared in a William Wyler film shot in Corsica, but wound up in an Israeli playground until the 1970s, when a collector took it back to England for restoration; Federal Express founder Fred Smith bought it in 1986.[77]

Memorials

- Sentinel is a sculpture by Tim Tolkien in Castle Bromwich, England, commemorating the main Spitfire factory.

- A sculpture of the prototype Spitfire, K5054, stands on the roundabout at the entrance to Southampton International Airport, which, as Eastleigh Aerodrome, saw the first flight of the aircraft in March 1936.

- There is also a Spitfire on display on the Thornaby Road roundabout near the school named after Douglas Bader who flew a Spitfire in the Second World War. This memorial is in memory of the old RAF base in Thornaby which is now a residential estate.

- One of the few Spitfires still in its original paint is displayed in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra; it has not been repainted since the Second World War.

- A fibreglass replica of a Spitfire has been mounted on a pole in Memorial Park, Hamilton, New Zealand as a tribute to all New Zealand fighter pilots who flew Spitfires during the Second World War.

- At Bentley Priory, London, fibreglass replicas of a Spitfire Mk.1 and a Hurricane Mk.1 can be seen fixed in a position of attack, diving on the Duchess' bedroom windows. This was built in memorial of everyone who worked at Bentley Priory during the War.

Operators

- See also: List of Supermarine Spitfire operators

Australia

Australia Belgium

Belgium Burma

Burma Canada

Canada Czechoslovakia

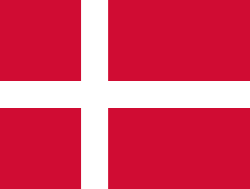

Czechoslovakia Denmark

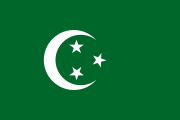

Denmark Egypt

Egypt France

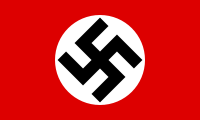

France Germany

Germany- (Captured)

Greece

Greece Hong Kong

Hong Kong India

India Ireland

Ireland Israel

Israel Italy

Italy- (co-belligerent Kingdom of Italy - post Sept. 1943 armistice)

Italy

Italy Netherlands

Netherlands New Zealand

New Zealand Norway

Norway Poland

Poland- [78]

Portugal

Portugal Rhodesia

Rhodesia South Africa

South Africa Soviet Union

Soviet Union Sweden

Sweden Syria

Syria Thailand

Thailand Turkey

Turkey United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States

United States Uruguay

Uruguay Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Popular culture

- The First of the Few (also known as Spitfire in the U.S. and Canada) (1942) was a British film produced and directed by Leslie Howard, with Howard in the starring role of R.J. Mitchell. It tells the story of Mitchell's life and how he developed the design for the famous British fighter aircraft. David Niven plays his friend and test pilot Geoffrey Crisp, who narrates the biography in flashback. Leslie Howard bore little resemblance to R.J. Mitchell, however, as Mitchell was a large and athletic man. Howard portrayed Mitchell as upper-class and mild-mannered. Mitchell – "the Guv'nor" – was in fact working-class and had an explosive temper; apprentices were told to watch the colour of his neck and to run if it turned red. Some of the footage includes film shot in 1941 of operational Spitfires and pilots of 501 Squadron (code letters SD).

- Malta Story (1953), starring Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Anthony Steel and Muriel Pavlow, is a black and white war film telling the story of the defence of Malta in 1942. At that time the RAF was mainly using the Mark V Spitfire, however this type appears only occasionally in the film, in archive footage. Otherwise, Spitfires shown are mainly of the Mark IX, XIV and XVI types, which flew from Malta after 1943-44. Also shown in archive footage are aircraft types used in the assault on Malta, such as the Italian SM.79, and the German Bf109F.

- Reach for the Sky (1956) starring Kenneth More tells the story of Douglas Bader; late mark Spitfires with 'teardrop' canopies, inappropriate for the period, were used for filming.

- Battle of Britain (1969) starring Sir Laurence Olivier, Michael Caine, Christopher Plummer, Ralph Richardson, Michael Redgrave, Susannah York and many others. Set in 1940, this film features several sequences involving a total of 12 flying Spitfires (mostly Mk IX versions), as well as a number of other flying examples of Second World War-era British and German aircraft. The film's production company was "Spitfire Productions, Steven S.A."

- British band Iron Maiden's song "Aces High" (1984) describes the aerial encounter between the RAF and Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain: "Bandits at 8 o'clock move in behind us, 10 ME 109s out of the sun, Ascending and turning our Spitfires to face them, Heading straight for them I press down my guns."

- Piece of Cake (1987) starring Tom Burlinson. When it aired on the ITV network in 1987, this was the most watched miniseries in history. Based on the novel by Derek Robinson, the six-part miniseries covered the prewar era to "Battle of Britain Day," 15 September 1940. The series had time to develop its large cast, and depicted the air combat over the skies of France and Britain during the early stages of the Second World War, though using five flying examples of late model Spitfires in place of the novel's early model Hawker Hurricanes. There were shots of several Spitfires taking off and landing together from grass airstrips.

- Dark Blue World (2001), starring Ondřej Vetchý was a film about a Free Czech pilot flying a Spitfire during the Second World War. Besides original footage, it also used out-takes from the earlier Battle of Britain film.

- American pilots in the movie Pearl Harbor (2001) are shown flying Spitfires during part of the film; Ben Affleck's character gets shot down over the English Channel.

- Several episodes of the ITV series Foyle's War (originally airing in 2001) focus on young RAF pilots who fly Spitfires. A real Spitfire Mark V was used in the filming.

- Spitfire Ace (2004) was a four-part mini series from RDF Media that depicted four young pilots undergoing the same training that Battle of Britain pilots would have received. One pilot was eventually selected to proceed to training in the "Grace Spitfire."

- English band The Prodigy's song "Spitfire" (2005) pays homage to the fighter with the repeated line "If I was in World War II, they'd call me Spitfire."

Specifications (Spitfire Mk Vb)

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[79] and Jane’s Fighting Aircraft of World War II[80]

General characteristics

- Crew: one pilot

- Length: 29 ft 11 in (9.12 m)

- Wingspan: 36 ft 10 in (11.23 m)

- Height: 11 ft 5 in (3.86 m)

- Wing area: 242.1 ft² (22.48 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 2200

- Empty weight: 5,090 lb (2,309 kg)

- Loaded weight: 6,622 lb (3,000 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 6,770 lb (3,071 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× Rolls-Royce Merlin 45 supercharged V12 engine, 1,470 hp at 9,250 ft (1,096 kW at 2,820 m)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 378 mph, (330 knots, 605 km/h)

- Combat radius: 410 nmi (470 mi, 760 km)

- Ferry range: 991 nmi (1,140 mi, 1,840 km)

- Service ceiling 35,000 ft (11,300 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,665 ft/min (13.5 m/s)

- Wing loading: 24.56 lb/ft² (119.91 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.22 hp/lb (360 W/kg)

Armament

- Guns: Mk I, Mk II, Mk VA

- 8x 0.303 inch (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, 350 rounds per gun

Later versions (VB on)

-

- 2× 20 mm (0.787 in) Hispano Mk II cannon, 60 (later 120 (Mk VC)) shells per gun

- 4× 0.303 inch (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, 350 rounds per gun

- Bombs:

- 2× 250 lb (110 kg) bombs

See also

- British military history of World War II

- Lucy, Lady Houston

- Rolls-Royce Merlin and Griffon

- Supermarine

- Allied Technological Cooperation During WW2

Related development

- Supermarine S.6B

- Supermarine Seafire

- Supermarine Spiteful

- Supermarine Seafang

Comparable aircraft

- Bell P-39

- Curtiss P-40

- Dewoitine D.520

- Focke Wulf Fw 190

- Hawker Hurricane

- Hawker Tempest

- Heinkel He 112

- Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien

- Macchi MC.202 Folgore

- Macchi C.205 Veltro

- Martin-Baker M.B.5

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-3

- North American P-51 Mustang

- Yakovlev Yak-9

Related lists

- List of most produced aircraft

- List of aircraft of the RAF

- List of aircraft of World War II

References

Notes

- a No official documents give a specific date for the first flight. However, a newspaper report dated March 5, quoted in The Chronicle of Aviation, says the flight occurred "today". According to test pilot Summers' logbook, which was filled out months later by his secretary, 5 March 1936 was the date. Another company test pilot, Jeffrey Quill, states the date was 6 March.[81]

- b The ellipse is proven to be the most efficient wing shape in terms of optimum spanwise lift distribution, whilst the associated chord tapering results in a high aspect ratio, important for lessening induced drag so that airflow does not "break" over the wing. Also of noteworthy importance is the type’s low thickness-to-chord ratio – the thin wings promote effective airflow, another vital factor in reducing drag.[82]

- c Starting with the Merlin XII fitted in Spitfire Mk IIs in late 1940 this was changed to a 70% water-30% glycol mix.

- d The theoretical aileron reversal speed with the new wing increased from 580 mph to 850 mph.

- e On the road between Salisbury and Andover there is a "Spitfire Lane" leading to the Chattis Hill aerodrome.

- f The test pilots were based at Highpost and flown by light aircraft to the other airfields.

- g There are conflicting accounts about the year TE330 was shipped to the US.

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ethel 1997, p. 12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ethell 1997, p. 117.

- ↑ Price 1986, p. 67.

- ↑ Green 1975

- ↑ Ethell 1997, p. 6.

- ↑ Avia.russia.ee Supermarine Type 224 Retrieved: 6 March 2007.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1987, p. 206.

- ↑ Price 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 16.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 17.

- ↑ Price 1977, p. 20.

- ↑ Price 1999, pp. 16, 17.

- ↑ Morgan and Shacklady 2000, p. 27.

- ↑ Gunston et al 1992, p. 334.

- ↑ Fleischman, John. "Best of Battle of Britain." Air & Space, March 2008. Retrieved: 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Ethell 1997, p. 11.

- ↑ Morgan and Shacklady 2000, p.45.

- ↑ Wikidictionary: spitfire Note: At the time, the name was associated with a girl or woman of that temperament.

- ↑ Deighton 1977, p. 99.

- ↑ Morgan and Shacklady, 1992.

- ↑ Spitfire construction Retrieved: 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Moss, Graham and Barry McKee. Spitfires and Polished Metal: Restoring the Classic Fighter. Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Airlife, 1999. ISBN 0-76030-741-5.

- ↑ Spitfire IX, XI and XVI described Retrieved: 10 April 2008.

- ↑ Price 1977, p. 32.

- ↑ Price 1977, pp. 33—34.

- ↑ Price 1977, p. 24.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Price 1999

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Andrews and Morgan 1987, p. 216.

- ↑ Morgan and Shacklady 2000 p. 4.

- ↑ Morgan and Morris 1940

- ↑ Morgan, M.B. R.A.E. Technical Note No. Aero 1106, March 1943.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1987, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Morgan and Shacklady 2000, pp. 464–475.

- ↑ Dibbs and Holmes 1997, p. 190.

- ↑ Tanner 1976, Section 1. Fig. 1.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Price 1982, p. 61.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 65.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Price 1982, p. 67.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 107.

- ↑ Castle Bromwich Retrieved: 9 February 2008.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 109.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Price 1982, p. 115.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Smallwood 1996, pp. 8–15.

- ↑ A worker at Woolston Retrieved: 9 February 2008.

- ↑ Discussion on Spitfire shadow sites Retrieved: 10 February 2008.

- ↑ Quill 1983, pp.138-145

- ↑ Spitfire Testing Retrieved: 9 September 2008.

- ↑ Price 1991, p.68

- ↑ Henshaw Retrieved: 9 February 2008.

- ↑ Price 1991, pp.68-69, 71

- ↑ Price and Spick 1997, p. 70.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 249.

- ↑ Lists of serial numbers/contracts Retrieved: 22 February 2008.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 67.

- ↑ www.merseyreporter.com/history/historic/woodvale/index.shtml

- ↑ Holland 2003, p. 232.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Aircraft performance and design (pdf file) pp. 5–6. Retrieved: 14 July 2008.

- ↑ Ted Powles

- ↑ Price 1991, p.99

- ↑ Quill 1993, p.135

- ↑ Spitfire: Simply Superb part three. Air International, Volume 28, Number 4. April 1985.

- ↑ Flintham 1990, pp. 254–263.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Price 2002, p.224

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Price 2002, p.223

- ↑ Price 2002, p.191

- ↑ Green 2007, p. 91.

- ↑ Price 1991, p. 158.

- ↑ List of Airworthy Spitfires Retrieved: 23 February 2008.

- ↑ Aviation Museum (AU)

- ↑ Hellenic Air Force Museum Spitfire

- ↑ Area 51.

- ↑ Spitfire at Fantasy of Flight

- ↑ Kent Spitfire Retrieved: 6 April 2008.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Spitfire fighter sold for $2.8m

- ↑ Kiwi aircraft images Retrieved: 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Stoke-on-Trent's own Spitfire Retrieved:27 March 2008.

- ↑ Brigid McMenamin, Sweet Dreams and Flying Machines, Forbes, 9 December 2002. Retrieved: 14 May 2008.

- ↑ List of Spitfire I and II aircraft used by Polish Air Force squadrons (PDF file)

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 2001

- ↑ Jane 1946, pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Price 1982, p. 37.

- ↑ Carpenter 1996

Bibliography

- Air Ministry. Spifire IIA and IIB Aeroplanes: Merlin XII Engine, Pilot's Notes. London: Air Data Publications, 1972. ISBN 0-85979-043-6

- Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan. Supermarine Aircraft since 1914. London:Putnam, 1987. ISBN 0 85177 800 3.

- Bader, Douglas. Fight for the Sky: The Story of the Spitfire and Hurricane. London: Cassell Military Books, 2004. ISBN 0-30435-674-3.

- Bungay, Stephen. The Most Dangerous Enemy – A History of the Battle Of Britain. London: Aurum, 2001. ISBN 1-85410-801-8.

- Carpenter, Chris. Flightwise: Part 1, Principles of Aircraft Flight. Shrewsbury, UK: AirLife, 1996. ISBN 1-85310-719-0.

- Cull, Brian with Fredrick Galea. Spitfires Over Malta: The Epic Air Battles of 1942. London: Grub Street, 2005. ISBN 1-904943-30-6

- Deighton, Len. Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain. London: Grafton 1977. ISBN 0-78581-208-3.

- Dibbs, John and Tony Holmes. Spitfire: Flying Legend. Southampton, UK: Osprey Publishing, 1997. ISBN 1-84176-005-6.

- Ethell, Jeffrey L. and Steve Pace. Spitfire. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1997. ISBN 0-7603-0300-2.

- Flack, Jeremy. Spitfire - The World's Most Famous Fighter. London: Chancellor Press, 1994. ISBN 1-85152-637-4.

- Flintham, Victor. Air Wars and Aircraft: A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present. New York: Facts on File, 1990. ISBN 0-81602-356-5.

- Green, Peter. "Spitfire Against a Lightning." Flypast No. 315, October 2007.

- Green, William. Famous Fighters of the Second World War, 3rd ed. New York: Doubleday, 1975. ISBN 0-356-08334-9.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Gueli, Marco. "Spitfire con Coccarde Italiane (Spitfire in Italian service)." (in Italian) Storia Militare n. 62, November 1998.

- Gunston, Bill et al. "Supermarine unveils its high-performance monoplane today (March 5)." The Chronicle of Aviation. Liberty, Missouri: JL International Publishing, 1992. ISBN 1-87203-130-7.

- Henshaw, Alex. Sigh for a Merlin: Testing the Spitfire: 2Rev Ed edition . London: Crecy Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-9475-5483-5.

- Holland, James. Fortress Malta: An Island Under Siege, 1940-1943. New York: Miramax Books, 2003. ISBN 1-4013-5186-7.

- Holmes, Tony. Spitfire vs Bf 109: Battle of Britain. London: Osprey Aerospace, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84603-190-8

- Jane, Fred T. “The Supermarine Spitfire.” Jane’s Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Jane, Fred T. Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II(reprint). New York: Crescent Books, 1998. ISBN 0-517-67964-7.

- McKinstry, Leo. Spitfire - Portrait of a Legend. London: John Murray, 2007. ISBN 0-71956-874-9.

- Morgan, Eric B. and Edward Shacklady. Spitfire: The History. London: Key Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0-946219-10-9.

- Morgan, M.B. and D. E. Morris. "Messerschmitt Me. 109 Handling and Manoeuvrability Tests, 5.4. Discussion." September 1940.

- Price, Alfred. Spitfire: A Documentary History. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1977. ISBN 0 354 01077 8.

- Price, Alfred. "Spitfire a Complete Fighting History". Enderby, Leicester, UK: The Promotional Reprint Company Limited, 1991. ISBN 1-85648-015-1

- Price, Alfred. The Spitfire Story. London: Jane's Publishing Company Ltd., 1982. ISBN 0-86720-624-1.

- Price, Alfred. The Spitfire Story: Second edition. London: Arms and Armour Press Ltd., 1986. ISBN 0-85368-861-3.

- Price, Alfred. Spitfire - Fighter Supreme. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1991. ISBN 1-85409-056-9.

- Price, Alfred. The Spitfire Story: New edited edition. London: Weidenfeld Military, 1999. ISBN 1-85409-514-5.

- Price, Alfred. The Spitfire Story: Revised second edition. Enderby, Leicester, UK: Siverdale Books, 2002. ISBN 1-885605-702-X.

- Price, Alfred and Spick, Mike. Handbook of Great Aircraft of WW II. Enderby, Leicester, UK: 1997. ISBN 0-78580-669-5.

- Quill. Jeffrey. Spitfire: A Test Pilot’s Story. London: Arrow Books, 1983. ISBN 0-09-937020-4.

- Shores, Christopher and Brian Cull with Nicola Malizia. Malta: The Spitfire Year. London: Grub Street, 1991. ISBN 0-948817-16-X.

- Smallwood, Hugh. Spitfire in Blue. London: Osprey Aerospace, 1996. ISBN 1-85532-615-9

- Spick, Mike. Supermarine Spitfire. New York: Gallery Books, 1990. ISBN 0-8317-14034.

- Tanner, John. The Spitfire V Manual (AP1565E reprint). London: Arms and Armour Press, 1981. ISBN 0-85368-420-0.

External links

- The Spitfire Society

- Alan Le Marinel hosts Supermarine Spitfire

- Spitfire Performance Testing

- Pacific Spitfires

- Warbird Alley: Spitfire page - Information about Spitfires still flying today

- K5054 - Supermarine Type 300 prototype Spitfire & production aircraft history

- Spitfire/Seafire Serial Numbers, production contracts and aircraft histories

- The Supermarine Spitfire in Indian Air Force Service

- The Spitfire: Seventy Years On - Includes images of the factory

- The Spitfire Site

- Spitfire Mk VIII and Mk XVI - Temora Aviation Museum page

- Airworthy Spitfires

- Supermarine Spitfire - History of a legend (RAF Museum)

- Article that presents the Norwegian history of famous Spitfire ML407 - The Grace Spitfire

- Spitfire restoration.com

- Airframe Assemblies.co.uk ; Company set up by ex-aviation archaeologist Steve Vizard manufacturing new components for Spitfires and for other aircraft types

- Spitfire IIA & IIB Pilot's Manual; Pdf file

- Spitfire IX, XI, XVI Pilot's Manual; Pdf file

- Spitfire Pilots, articles about Spitfires and its pilots

- RAF Museum Spitfire Mk VB photos

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||