Sunscreen

Sunscreen (also known as sunblock or suntan lotion[1]) is a lotion, spray, gel or other topical product that absorbs or reflects the sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation and protects the skin.

Sunscreens contain one or more UV filters of which there are three main types[2] :

- Organic chemical compounds that absorb ultraviolet light (such as oxybenzone)

- Inorganic particulates that reflect, scatter, and absorb UV light (such as titanium dioxide, zinc oxide), or a combination of both.

- Organic particulates that mostly absorb light like organic chemical compounds, but contain multiple chromophores, may reflect and scatter a fraction of light like inorganic particulates, and behave differently in formulations than organic chemical compounds. An example is Tinosorb M.

Medical organizations such as the American Cancer Society recommend the use of sunscreen because it prevents the squamous cell carcinoma and the basal cell carcinoma.[3] However, several epidemiological studies indicate an increased risk of malignant melanoma for the sunscreen user.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11] Despite these studies, no medical association has published recommendations to not use sunblock. Different meta-analysis publications have concluded that the evidence is not yet sufficient to claim a positive correlation between sunscreen use and malignant melanoma.[12][13]

Contents |

Dosing

The dose used in FDA sunscreen testing is 2 mg/cm² of exposed skin.[14] Provided one assumes an "average" adult build of height 5 ft 4 in (163 cm) and weight 150 lb (68 kg) with a 32 in (82 cm) waist, that adult wearing a bathing suit covering the groin area should apply 29 g (approximately 1 oz) evenly to the uncovered body area. Considering only the face, this translates to about 1/4 to 1/3 of a teaspoon for the average adult face.

Contrary to the common advice that sunscreen should be reapplied every 2–3 hours, some research has shown that the best protection is achieved by application 15–30 minutes before exposure, followed by one reapplication 15–30 minutes after the sun exposure begins. Further reapplication is only necessary after activities such as swimming, sweating, and rubbing.[15]

However, more recent research at the University of California, Riverside, indicates that sunscreen needs to be reapplied within 2 hours in order to remain effective. Not reapplying could even cause more cell damage than not using sunscreen at all, due to the release of extra free radicals from those sunscreen chemicals which were absorbed into the skin.[16] Some studies have shown that people commonly apply only 1/2 to 1/4 of the amount recommended to achieve the rated SPF, and the effective SPF should be downgraded to a square or 4th root of the advertised value. [17]

History

The first effective sunscreen may have been developed by chemist Franz Greiter in 1938. The product, called Gletscher Crème (Glacier Cream), subsequently became the basis for the company Piz Buin (named in honor of the place Greiter allegedly obtained the sunburn that inspired his concoction), which today is a well-known marketer of sunscreen products. Some suggest that Gletscher Crème had a sun protection factor of 2.

The first widely used sunscreen was produced by Benjamin Greene, an airman and later a pharmacist, in 1944. The product, Red Vet Pet (for red veterinary petrolatum), had limited effectiveness, working as a physical blocker of ultraviolet radiation. It was a disagreeable red, sticky substance similar to petroleum jelly. This product was developed during the height of World War II, when it was likely that the hazards of sun overexposure were becoming apparent to soldiers in the Pacific and to their families at home.

Franz Greiter is credited with introducing the concept of Sun Protection Factor (SPF) in 1962, which has become a worldwide standard for measuring the effectiveness of sunscreen when applied at an even rate of 2 milligrams per square centimeter (mg/cm2). Some controversy exists over the usefulness of SPF measurements, especially whether the 2 mg/cm2 application rate is an accurate reflection of people’s actual use.

Newer sunscreens have been developed with the ability to withstand contact with water and sweat.

Measurements of sunscreen protection

Sun protection factor

The SPF of a sunscreen is a laboratory measure of the effectiveness of sunscreen - the higher the SPF, the more protection a sunscreen offers against UV-B (the ultraviolet radiation that causes sunburn). The SPF indicates the time a person with sunscreen applied can be exposed to sunlight before getting sunburn relative to the time a person without sunscreen can be exposed. For example, someone who would burn after 12 minutes in the sun would expect to burn after 120 minutes if protected by a sunscreen with SPF 10. In practice, the protection from a particular sunscreen depends on factors such as:

- The skin type of the user.

- The amount applied and frequency of re-application.

- Activities in which one engages (for example, swimming leads to a loss of sunscreen from the skin).

- Amount of sunscreen the skin has absorbed.

The SPF is an imperfect measure of skin damage because invisible damage and skin aging is also caused by the very common ultraviolet type A, which does not cause reddening or pain. Conventional sunscreen does not block UVA as effectively as it does UVB, and an SPF rating of 30+ may translate to significantly lower levels of UVA protection according to a 2003 study. According to a 2004 study, UVA also causes DNA damage to cells deep within the skin, increasing the risk of malignant melanomas.[18] Even some products labeled "broad-spectrum UVA/UVB protection" do not provide good protection against UVA rays.[19] The best UVA protection is provided by products that contain zinc oxide, avobenzone, and ecamsule. Titanium dioxide probably gives good protection, but does not completely cover the entire UV-A spectrum.[20]

Owing to consumer confusion over the real degree and duration of protection offered, labeling restrictions are in force in several countries. The United States does not have mandatory, comprehensive sunscreen standards, although a draft rule has been under development since 1978. In the 2007 draft rule, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed to institute the labelling of SPF 50+ for sunscreens offering more protection. This and other measures were proposed to limit unrealistic claims about the level of protection offered (such as "all day protection").[21] In the EU sunscreens are limited to SPF 50+, indicating a SPF of 60 or higher, and Australia's upper limit is 30.[22]

The SPF can be measured by applying sunscreen to the skin of a volunteer and measuring how long it takes before sunburn occurs when exposed to an artificial sunlight source. In the US, such an in vivo test is required by the FDA. It can also be measured in vitro with the help of a specially designed spectrometer. In this case, the actual transmittance of the sunscreen is measured, along with the degradation of the product due to being exposed to sunlight. In this case, the transmittance of the sunscreen must be measured over all wavelengths in the UV-B range (290–320 nm), along with a table of how effective various wavelengths are in causing sunburn (the erythemal action spectrum) and the actual intensity spectrum of sunlight (see the figure). Such in vitro measurements agree very well with in vivomeasurements. .[23] Numerous methods have been devised for evalaution of UVA and UVB protection The most reliable spectrophotochemical methods eliminate the subjective nature of grading erythema. [24]

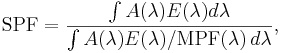

Mathematically, the SPF is calculated from measured data as

where  is the solar irradiance spectrum,

is the solar irradiance spectrum,  the erythemal action spectrum, and

the erythemal action spectrum, and  the monochromatic protection factor, all functions of the wavelength

the monochromatic protection factor, all functions of the wavelength  . The MPF is roughly the inverse of the transmittance at a given wavelength.

. The MPF is roughly the inverse of the transmittance at a given wavelength.

The above means that the SPF is not simply the inverse of the transmittance in the UV-B region. If that were true, then applying two layers of SPF 5 sunscreen would be equivalent to SPF 25 (5 times 5). The actual combined SPF is always lower than the square of the single-layer SPF.

Measurements of UVA protection

Persistent Pigment Darkening (PPD), Immediate Pigment Darkening (IPD), Boots Star System, Japanese PA system

The Persistent Pigment Darkening (PPD) method is a method of measuring UVA protection, similar to the SPF method of measuring UVB light protection. Originally developed in Japan, it is the preferred method used by manufacturers such as L'Oreal.

Instead of measuring erythema or reddening of the skin, the PPD method uses UVA radiation to cause a permanent darkening or tanning of the skin. Theoretically, a sunscreen with a PPD rating of 10 should allow you to endure 10 times as much UVA as you would without protection. The PPD method is an in-vivo test like SPF. In addition, Colipa has introduced a method which is claimed can measure this in-vitro and provide parity with the PPD method.[25]

As part of revised guidelines for sunscreens in the EU, there is a requirement to provide the consumer with a minimum level of UVA protection in relation to the SPF. This should be a UVA PF of at least 1/3 of the SPF to carry the UVA seal. The implementation of this seal is in its phase-in period, so a sunscreen without it may already offer this protection.[26]

Star rating system

In the UK and Ireland, the Boots star rating system is a proprietary in vitro method used to describe the ratio of UVA to UVB protection offered by sunscreen creams and sprays. Invented by Dr Diffey of the Boots Company in Nottingham, UK, it has been adopted by most companies marketing these products in the UK. The logo and methodology of the test are freely licenced to any manufacturer or brand of sunscreens that wishes to place products on the UK market. It should not be confused with SPF, which is measured with reference to burning and UVB. One-star products provide the least ratio of UVA protection, five-star products are best. The method has recently been revised in the light of the Colipa UVA PF test, and with the new EU recommendations regarding UVA PF. The method still uses a spectrophotometer to measure absorption of UVA vs UVB, the difference stems from a requirement to pre-irradiate samples (where this was not previously required) to give a better indication of UVA protection, and of photostability when the product is used. With the current methodology, the lowest rating is three stars, the highest being five stars.

Active ingredients

The principal ingredients in sunscreens are usually aromatic molecules conjugated with carbonyl groups. This general structure allows the molecule to absorb high-energy ultraviolet rays and release the energy as lower-energy rays, thereby preventing the skin-damaging ultraviolet rays from reaching the skin. So, upon exposure to UV light, most of the ingredients (with the notable exception of avobenzone) do not undergo significant chemical change, allowing these ingredients to retain the UV-absorbing potency without significant photodegradation.[14] A chemical stabilizer is included in some sunscreens containing avobenzone to slow its breakdown - examples include formulations containing Helioplex[27] and AvoTriplex.[28] The stability of avobenzone can also be improved by bemotrizinol,[29] octocrylene[30] and various other photostabilisers.

Some sunscreens also include enzymes like photolyase, which are claimed to be able to repair UV-damaged DNA.[31]

FDA allowable ingredients

The following are the FDA allowable active ingredients in sunscreens:

| UV-filter | other names | maximum concentration | permitted in these countries | Results of safety testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Aminobenzoic acid | PABA | 15% (5% EC) | EC, USA, AUS | Protects against skin tumors in mice.[32][33][34] |

| Padimate O | OD-PABA, octyldimethyl-PABA, σ-PABA | 8% | EC, USA, AUS | not tested |

| Phenylbenzimidazole sulfonic acid | Ensulizole, Eusolex 232, PBSA, Parsol HS | 4%(US,AUS) 8%(EC) | EC,USA, AUS | Genotoxic in bacteria[35] |

| Cinoxate | 2-Ethoxyethyl p-methoxycinnamate | 3%(US) 6%(AUS) | USA, AUS | not tested |

| Dioxybenzone | benzophenone-8 | 3% | USA, AUS | not tested |

| Oxybenzone | benzophenone-3, Eusolex 4360, Escalol 567 | 6%(US) 10%(AUS) | EC, USA, AUS | not tested |

| Homosalate | Homomethyl salicylate, HMS | 10%(EC) 15%(US,AUS) | EC, USA, AUS | not tested |

| Methyl anthranilate | Methyl-aminobenzoate, meradimate | 5% | USA, AUS | not tested |

| Octocrylene | Eusolex OCR, 2-cyano-3,3diphenyl acrylic acid, 2-ethylhexylester | 10% | EC,USA, AUS | Increases ROS[16] |

| Octyl methoxycinnamate | Octinoxate, EMC, OMC, Ethylmethoxycinnamate, Escalol 557, 2-ethylhexyl-paramethoxycinnamate, Parsol MCX | 7.5%(US) 10%(EC,AUS) | EC,USA, AUS | Protects against skin tumors in mice[36] |

| Octyl salicylate | Octisalate, 2-Ethylhexyl salicylate, Escalol 587, | 5% | EC,USA, AUS | not tested |

| Sulisobenzone | 2-Hydroxy-4-Methoxybenzophenone-5-sulfonic acid,

3-benzoyl-4-hydroxy-6-methoxybenzenesulfonic acid, BENZ-4, Escalol 577 |

5%(EC) 10%(US, AUS) | EC,USA, AUS | Protects against skin tumors in mice [36] |

| Trolamine salicylate | Triethanolamine salicylate | 12% | USA, AUS | not tested |

| Avobenzone | 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-(4-tert-butylphenyl)propane-1,3-dione, Butyl methoxy dibenzoylmethane, BMDBM, Parsol 1789, Eusolex 9020 | 3%(US) 5%(EC,AUS) | EC, USA, AUS | Not available[37] |

| Ecamsule | Mexoryl SX, Terephthalylidene Dicamphor Sulfonic Acid | 10 | EC, USA, AUS | Protects against skin tumors in mice[38][39][40] |

| Titanium dioxide | CI77891 | 25% | EC,USA, AUS | not tested |

| Zinc oxide | 25%(US) 20%(AUS) (EC)Not listed as sunscreen, Still under SCCP review | EC,USA, AUS | Protects against skin tumors in mice[38][36] |

Other ingredients approved within the EU[41] and other parts of the world, [42] which have not been included in the current FDA Monograph:

| UV-filter | other names | maximum concentration | permitted in |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Methylbenzylidene camphor | Enzacamene, Parsol 5000, Eusolex 6300, MBC | 4% | EC, AUS |

| Tinosorb M | Bisoctrizole, Methylene Bis-Benzotriazolyl Tetramethylbutylphenol,MBBT | 10% | EC, AUS |

| Tinosorb S | Bis-ethylhexyloxyphenol methoxyphenol triazine, Bemotrizinol, BEMT, anisotriazine | 10% | EC, AUS |

| Neo Heliopan AP | Bisdisulizole Disodium, Disodium phenyl dibenzimidazole tetrasulfonate, bisimidazylate, DPDT | 10% | EC, AUS |

| Mexoryl XL | Drometrizole Trisiloxane | 15% | EC, AUS |

| Uvinul T 150 | Octyl triazone, ethylhexyl triazone, ET | 5% | EC, AUS |

| Uvinul A Plus | Diethylamino Hydroxybenzoyl Hexyl Benzoate | 10% (EC) | EC |

| Uvasorb HEB | Iscotrizinol, Diethylhexyl butamido triazone, DBT | 10% | EC |

| Parsol SLX | Dimethico-diethylbenzalmalonate, Polysilicone-15 | 10% | EC, AUS |

| Isopentenyl-4-methoxycinnamate | Isoamyl p-Methoxycinnamate, IMC, Neo Heliopan E1000, Amiloxate | 10% | EC, AUS |

Many of the ingredients not approved by the FDA are relatively new and developed to absorb UVA.[43]

Potential health risks

Adverse health effects may be associated with some synthetic compounds in sunscreens.[44] In 2007 two studies by the CDC highlighted concerns about the sunscreen chemical oxybenzone (benzophenone-3). They first detected the chemicals in greater than 95% of 2000 Americans tested, and the second found that mothers with high levels of oxybenzone in their bodies were more likely to give birth to underweight baby girls. [45]

See also

- Slip-Slop-Slap - famous Australian sun safety advertising jingle

- "Wear Sunscreen" - a column by Mary Schmich in the form of a speech that became a music single and then made into a music video that became viral on the internet

- Indoor tanning lotion

- Sun protective clothing

References

- ↑ Nassau County Health Department Jacksonville online

- ↑ Shaath, N. (2005). "The Chemistry of Ultraviolet Filters," in Regulations and Commericial Development 3rd edition, edited by N. Shaath, Taylor and Francis Press, New York. 954pp, 2005.

- ↑ [1] What You Need To Know About Skin Cancer

- ↑ Garland C, Garland F, Gorham E (04/01/1992). "Could sunscreens increase melanoma risk?". Am J Public Health 82 (4): 614–5. PMID 1546792. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/82/4/614.

- ↑ Westerdahl J; Ingvar C; Masback A; Olsson H (2000). "Sunscreen use and malignant melanoma". International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 87: 145–50. doi:.

- ↑ Autier P; Dore J F; Schifflers E; et al (1995). "Melanoma and use of sunscreens: An EORTC case control study in Germany, Belgium and France". Int. J. Cancer 61: 749–755. doi:.

- ↑ Weinstock, M. A. (1999). "Do sunscreens increase or decrease melanoma risk: An epidemiologic evaluation". Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings 4: 97–100. doi:.

- ↑ Vainio, H., Bianchini, F. (2000). "Cancer-preventive effects of sunscreens are uncertain". Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health 26: 529–31.

- ↑ Wolf P, Quehenberger F, Müllegger R, Stranz B, Kerl H. (1998). "Phenotypic markers, sunlight-related factors and sunscreen use in patients with cutaneous melanoma: an Austrian case-control study". Melanoma Res. 8 (4): 370–378. doi:. PMID 9764814.

- ↑ Graham S, Marshall J, Haughey B, Stoll H, Zielezny M, Brasure J, West D. (1985). "An inquiry into the epidemiology of melanoma". Am J Epidemiol. 122 (4): 606–619. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxy.its.uu.se/sites/entrez.

- ↑ Beitner H, Norell SE, Ringborg U, Wennersten G, Mattson B. (1990). "Malignant melanoma: aetiological importance of individual pigmentation and sun exposure". Br J Dermatol. 122 (1): 43–51. doi:. PMID 2297503.

- ↑ Huncharek M, Kupelnick B (July 2002). "Use of topical sunscreens and the risk of malignant melanoma: a meta-analysis of 9067 patients from 11 case-control studies". Am J Public Health 92 (7): 1173–7. PMID 12084704. PMC: 1447210. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12084704.

- ↑ Dennis LK, Beane Freeman LE, VanBeek MJ (December 2003). "Sunscreen use and the risk for melanoma: a quantitative review". Ann. Intern. Med. 139 (12): 966–78. PMID 14678916.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dailys/00/Sep00/090600/c000573_10_Attachment_F.pdf

- ↑ Diffey B (2001). "When should sunscreen be reapplied?". J Am Acad Dermatol 45 (6): 882–5. doi:. PMID 11712033.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Kerry M. Hanson, Enrico Gratton and Christopher J. Bardeen (2006). "Sunscreen enhancement of UV-induced reactive oxygen species in the skin". Free Radical Biology and Medicine 11: 1205. doi:.

- ↑ Faurschou A, Wulf HC (April 2007). "The relation between sun protection factor and amount of suncreen applied in vivo". Br. J. Dermatol. 156 (4): 716–9. doi:. PMID 17493070.

- ↑ Berneburg M, Plettenberg H, Medve-König K, Pfahlberg A, Gers-Barlag H, Gefeller O, Krutmann J (2004). "Induction of the photoaging-associated mitochondrial common deletion in vivo in normal human skin". J Invest Dermatol 122 (5): 1277–83. doi:. PMID 15140232.

- ↑ Sunscreen—protection or 'snake oil?' - - MSNBC.com

- ↑ Pinnell SR, Fairhurst D, Gillies R, Mitchnick MA, Kollias N (April 2000). "Microfine zinc oxide is a superior sunscreen ingredient to microfine titanium dioxide". Dermatol Surg 26 (4): 309–14. doi:. PMID 10759815. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1076-0512&date=2000&volume=26&issue=4&spage=309.

- ↑ Questions and Answers on the 2007 Sunscreen Proposed Rule

- ↑ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:265:0039:0043:EN:PDF

- ↑ Optometrics products

- ↑ Dominique Moyal "How to measure UVA protection afforded by suncreen products" www.medscape.com/viewarticle/576849

- ↑ Colipa UVA method

- ↑ www.colipa.com

- ↑ Neutrogena | How Helioplex Works

- ↑ Banana Boat AvoTriplex

- ↑ Chatelain E, Gabard B. (September 2001). "Photostabilization of Butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane (Avobenzone) and Ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate by Bis-ethylhexyloxyphenol methoxyphenyl triazine (Tinosorb S), a new UV broadband filter". Photochem Photobiol 74(3): 401–6. doi:. PMID 11594052.

- ↑ DSM Nutritional Products North America - Cosmetics: Basis for Performance - Parsol 340 - Octocrylene

- ↑ Dagmar Kulms, Birgit Pöppelmann, Daniel Yaroshdagger, Thomas A. Luger, Jean KrutmannDagger and Thomas Schwarz (1999). Nuclear and cell membrane effects contribute independently to the induction of apoptosis in human cells exposed to UVB radiation PNAS 96(14):7974-7979

- ↑ H Flindt-Hansen; P. Thune, T. Eeg-Larsen (1990). "The inhibiting effect of PABA on photocarcinogenesis". Archives of Dermatological Research 282: 38–41. doi:.

- ↑ H Flindt-Hansen; P. Thune, T. Eeg-Larsen (1990). "The effect of short-term application of PABA on photocarcinogenesis". Acta Derm Venerol. 70: 72–75.

- ↑ P. J. Osgood; S. H. Moss, D. J. Davies (1982). "The sensitization of near-ultraviolet radiation killing of mammalian cells by the sunscreen agent para-aminobenzoic acid". Journal of Investigative Dermatology 79 (6): 354–357. doi:.

- ↑ Mosley, C N; Wang, L; Gilley, S; Wang, S; Yu, H (2007). "Light-Induced Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of a Sunscreen Agent, 2-Phenylbenzimidazol in Salmonella typhimurium TA 102 and HaCaT Keratinocytes". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 4 (2): 126–131.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Nohynek G. J.; Schaefer H (2001). "Benefit and Risk of Organic Ultraviolet Filters". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 33 (3): 285–299. doi:. PMID 11407932.

- ↑ Nash,JF (2006). "Human Safety and Efficacy of Ultraviolet Filters and Sunscreen Products". Dermatologic Clinics 24: 35–51. doi:.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Lautenschlager, Stephan; Wulf, Hans Christian; Pittelkow, Mark R. (2007). "photoprotection". Lancet 370: 528–37. doi:.

- ↑ Benech-Kieffer F, Meuling WJ, Leclerc C, Roza L, Leclaire J, Nohynek G (Nov-Dec 2003). "Percutaneous absorption of Mexoryl SX in human volunteers: comparison with in vitro data". Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 16(6): 343–55. doi:. PMID 14528058.

- ↑ Fourtanier A (October 1996). "Mexoryl SX protects against solar-simulated UVR-induced photocarcinogenesis in mice". Photochem Photobiol 64(4): 688–93. doi:. PMID 8863475.

- ↑ CL1976L0768EN0150010.0001 1..107

- ↑ Australian Regulatory Guidelines for OTC Medicines - Chapter 10

- ↑ Manage Account - Modern Medicine

- ↑ Experts explore the safety of sunscreen | Straight.com

- ↑ CDC: Americans Carry Body Burden of Toxic Sunscreen Chemical | Environmental Working Group

External links

- * FDA monograph on sunscreen

- * FDA monograph on dosing, mechanism of action, and photodegradation of sunscreen (PDF file)

- Make sure your sunscreen has The Skin Cancer Foundation's Seal of Recommendation

- Environmental Working Group: June 2008 Sunscreen Safety Database and Report

- Information on what sunscreens are and how they work from The Skin Cancer Foundation

- Sunscreen protection calculator

- Sun Safety for Babies and Children University of Florida/IFAS Extension Department of Family, Youth and Community Sciences

- Article on UV absorbers not yet approved by the FDA

- Radiation protectants and their CAS registry number

- European Cosmetics ingredient database (CosIng)