Sumo

| Sumo (相撲) | |

|---|---|

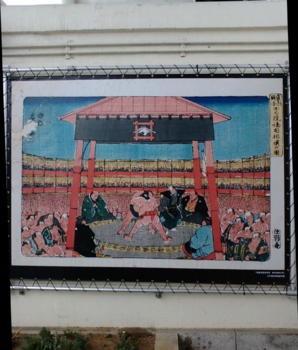

A sumo match (tori-kumi) between Yokozuna Asashoryu and Komusubi Kotoshogiku in January 2008. |

|

| Focus | Grappling |

| Hardness | Full-contact |

| Country of origin | |

| Olympic Sport | No |

| Official Site | http://www.sumo.or.jp/eng/ |

Sumo (相撲 sumō?) is a competitive contact sport where a wrestler (rikishi) attempts to force one another out of a circular ring (dohyo) or to touch the ground with anything other than the soles of the feet. The sport originated in Japan, the only country where it is practiced professionally. The Japanese consider sumo a gendai budō (a modern Japanese martial art), though the sport has a history spanning many centuries.

The sumo tradition is very ancient, and even today the sport includes many ritual elements, such as the use of salt for purification, from the days sumo was used in the Shinto religion. Life as a rikishi is highly regimented, with rules laid down by the Sumo Association. Professional sumo wrestlers are required to live in communal "sumo training stables" known in Japanese as heya where all aspects of their daily lives—from meals to their manner of dress—are dictated by strict tradition.

Origins of sumo

In addition to its use as a trial of strength in combat, it has also been associated with Shinto ritual, and even today certain shrines carry out forms of ritual dance where a human is said to wrestle with a kami (a Shinto divine spirit). It was an important ritual at the imperial court. Representatives of each province were ordered to attend the contest at the court and fight. They were required to pay for their travels themselves. The contest was known as sumai no sechie,, or "sumai party."

Over the rest of Japanese recorded history, sumo's popularity has changed according to the whims of its rulers and the need for its use as a training tool in periods of civil strife. The form of wrestling combat probably changed gradually into one where the main aim in victory was to throw one's opponent. The concept of pushing one's opponent out of a defined area came some time later.

It is believed that a ring, defined by more than the area given to the wrestlers by spectators, came into being in the 16th century as a result of a tournament organized by the then principal warlord in Japan, Oda Nobunaga. At this point wrestlers would wear loose loincloths, rather than the much stiffer mawashi of today. During the Edo period, wrestlers would wear a fringed kesho-mawashi during the bout, whereas today these are worn only during pre-tournament rituals. Most of the rest of the current forms within the sport developed in the early Edo period.

Professional sumo (大相撲 ōzumō?) can trace its roots back to the Edo Period in Japan as a form of sporting entertainment. The original wrestlers were probably samurai, often ronin, who needed to find an alternative form of income. Current professional sumo tournaments begun in the Tomioka Hachiman Shrine in 1684, and then were held in the Ekō-in in the Edo period. They have been held in the Kokugikan since 1909.

Nations adjacent to Japan, sharing many cultural traditions, also feature styles of traditional wrestling that bear resemblance to sumo. Notable examples include Mongolian wrestling, Chinese Shuai jiao (摔角), and Korean Ssireum. Examples of Chinese art from 220 BCE show the wrestlers stripped to the waist and their bodies pressed shoulder to shoulder.[1]

Winning a sumo bout

The winner of a sumo bout is either:

- The first wrestler to force his opponent to step out of the ring.

- The first wrestler to force his opponent to touch the ground with any part of his body other than the bottom of his feet.

On rare occasions the referee or judges may award the win to the wrestler who touched the ground first; this happens if both wrestlers touch the ground at nearly the same time and it is decided that the wrestler who touched the ground second had no chance of winning as, due to the superior sumo of his opponent, he was already in an irrecoverable position. The losing wrestler is referred to as being shini-tai (“dead body”) in this case.

There are also a number of other rarely used rules that can be used to determine the winner. For example a wrestler using an illegal technique (or kinjite) automatically loses, as does one whose mawashi (or belt) becomes completely undone. A wrestler failing to turn up for his bout (including through a prior injury) also automatically loses (fusenpai). After the winner is declared, an off-stage gyoji (or referee) determines the kimarite (or winning technique) used in the bout, which is then announced to the audience.

Matches often last only a few seconds, as usually one wrestler is quickly ousted from the circle or thrown to the ground. However, they can occasionally last for several minutes. Each match is preceded by an elaborate ceremonial ritual. The wrestlers themselves are renowned for their great girth, as body mass is often a winning factor in sumo, though with skill, smaller wrestlers can topple far larger opponents.[2]

The wrestling ring (dohyō)

Sumo matches take place in a dohyō (土俵): a ring, 4.55 metres in diameter, of rice-straw bales on top of a platform made of clay mixed with sand. Its area is 8281π/1600 metres squared and its perimeter is 91π/20 meters. A new dohyō is built for each tournament by the yobidashi. At the center are two white lines, the shikiri-sen, behind which the wrestlers position themselves at the start of the bout.[3] A roof resembling that of a Shinto shrine may be suspended over the dohyō.

Professional sumo

Professional sumo is organized by the Japan Sumo Association.[4] The members of the association, called oyakata, are all former wrestlers, and are the only people entitled to train new wrestlers. All practising wrestlers are members of a training stable (heya) run by one of the oyakata, who is the stablemaster for the wrestlers under him. Currently there are 54 training stables for about 700 wrestlers.[5]

All sumo wrestlers take wrestling names called shikona (しこ名), which may or may not be related to their real names. Often wrestlers have little choice in their name, which is given to them by their trainer (or stablemaster), or by a supporter or family member who encouraged them into the sport. This is particularly true of foreign-born wrestlers. A wrestler may change his wrestling name several times during his sumo career.[4] The current trend is for more wrestlers, particularly native Japanese, to keep their own name rather than change it.

Sumo wrestling is a strict hierarchy based on sporting merit. The wrestlers are ranked according to a system that dates back hundreds of years, to the Edo period. Wrestlers are promoted or demoted according to their previous performance, and a carefully prepared banzuke listing the full hierarchy is published two weeks prior to each sumo tournament.

Sumo divisions

There are six divisions in sumo: makuuchi (fixed at 42 wrestlers), jūryō (fixed at 28 wrestlers), makushita (fixed at 120 wrestlers), sandanme (fixed at 200 wrestlers), jonidan (approximately 230 wrestlers), and jonokuchi (approximately 80 wrestlers). Wrestlers enter sumo in the lowest jonokuchi division and, ability permitting, work their way up to the top division. Wrestlers in the top two divisions are known as sekitori, while lower division wrestlers are generally referred to by the generic term for wrestlers, rikishi.[6]

The topmost makuuchi division receives the most attention from fans and has the most complex hierarchy. The majority of wrestlers are maegashira and are numbered from one (at the top) down to about sixteen or seventeen. Above the maegashira are the three champion or titleholder ranks, called the sanyaku. These are, in ascending order, komusubi, sekiwake, and ōzeki. At the pinnacle of the ranking system is the rank of yokozuna.[6]

Yokozuna, or grand champions, are generally expected to be regularly in competition to win the top division tournament title. Hence the promotion criteria for yokozuna are very strict. In general, an ōzeki must win the championship for two consecutive tournaments or an "equivalent performance" to be considered for promotion to yokozuna.[4].

Exhibition competitions are held at regular intervals every year in Japan, and approximately once every two years the top ranked wrestlers visit a foreign country for such exhibitions. None of these displays are taken into account in determining a wrestler's future rank. Rank is determined only by performance in Grand Sumo Tournaments (or honbasho), which are described in more detail below.[3]

Foreign participation

Professional sumo is practiced exclusively in Japan, but wrestlers of other nationalities participate. There are currently 59 wrestlers officially listed as foreigners.[7] In July 2007, there were 19 foreigners in the top two divisions, an all-time record, and for the first time, a majority of wrestlers in the top sanyaku ranks were from overseas.[8]

A Japanese-American, Toyonishiki, and the Korean-born Rikidozan achieved sekitori status prior to World War II, but neither were officially listed as foreigners. The first non-Asian to achieve fame and fortune in sumo was Hawaii-born Takamiyama. He reached the top division in 1968 and in 1972 became the first foreigner to win the top division championship. He was followed by fellow Hawaii-born Konishiki, the first foreigner to reach the rank of ōzeki in 1987; and the native Hawaiian Akebono, who became the first foreign-born yokozuna in 1993. Musashimaru, born in Samoa but from Hawaii, became the second foreigner to reach sumo's top rank in 1999. Both of the current yokozuna, Asashōryū and Hakuhō, are Mongolian. They are among a group of Mongolian wrestlers who have achieved success in the upper ranks. Wrestlers from Eastern Europe countries such as Georgia and Russia have also found success in the upper levels of sumo. In 2005 Kotoōshū from Bulgaria became the first wrestler of European birth to attain the ōzeki ranking.

Until relatively recently, the Japan Sumo Association had no restrictions at all on the number of foreigners allowed in professional sumo. In May 1992, shortly after the Ōshima stable had recruited six Mongolians at the same time, the Sumo Association's new director Dewanoumi, the former yokozuna Sadanoyama, announced that he was considering limiting the number of overseas recruits per stable and in sumo overall.[4] There was no official ruling, but no stable recruited any foreigners for the next six years.[9] This unofficial ban was then relaxed, but only two new foreigners per stable were allowed, until the total number reached 40.[9] Then in 2002, a one foreigner per stable policy was officially adopted. (The ban was not retroactive, so foreigners recruited before the changes were unaffected). Though the move has been met with criticism, there are no plans to relax the restrictions at this time.[9] However, it is possible for a place in a heya to be opened up if a foreign born wrestler acquires Japanese citizenship. This occurred when Hisanoumi changed his nationality from Tongan at the end of 2006, allowing another Tongan to enter his stable,[10] and Kyokutenhō's change of citizenship allowed Ōshima stable to recruit Mongolian Kyokushuho in May 2007.

Professional sumo tournaments

There are six Grand Sumo tournaments (or honbasho) each year: three at The Sumo Hall (or Ryōgoku Kokugikan) in Ryōgoku, Tokyo (January, May, and September), and one each in Osaka (March), Nagoya (July) and Fukuoka (November). Each tournament begins on a Sunday and runs for 15 days, ending also on a Sunday.[11] Each wrestler in the top two divisions (sekitori) has one match per day, while the lower ranked rikishi compete in seven bouts, approximately one every two days.

Each day is structured so the highest-ranked contestants compete at the end of the day. Thus, wrestling will start in the morning with the jonokuchi wrestlers and end at around six o'clock in the evening with bouts involving the yokozuna, or the ōzeki in the case of the yokozuna's absence. The wrestler who wins the most matches over the fifteen days wins the tournament championship (yūshō). If two wrestlers are tied for the top, they wrestle each other and the winner takes the title. Three-way ties for the top position are rare, at least in the top division. In these cases the three wrestle each other in pairs with the first to win two in a row taking the tournament. More complex systems for championship playoffs involving four or more wrestlers also exist, but these are usually only seen in determining the winner of one of the lower divisions.

The matchups for each day of the tournament are announced a day in advance. They are determined by oyakata (or sumo elders) who are members of the judging division of the Sumo Association. As there are many more wrestlers in each division than matchups during the tournament each wrestler will only compete against a selection of opponents, mostly from the same division. With the exception of the sanyaku ranked wrestlers the first bouts tend to be between wrestlers who are within a couple of ranks of each other. Afterwards the selection of opponents takes into account a wrestler's prior performance. For example in the lower divisions the last matchups often involve undefeated wrestlers competing against each other, even if they are from opposite ends of the division. In the top division in the last few days wrestlers with exceptional records will often have matches against much more highly ranked opponents, including sanyaku wrestlers, especially if they are still in the running for the top division championship. Similarly more highly ranked wrestlers with very poor records may find themselves fighting wrestlers much further down the division. For the yokozuna and ōzeki the first week and a half of the tournament tends to be taken up with bouts against the top maegashira, the komusubi and sekiwake, with the bouts between them being concentrated into the last five days or so of the tournament (depending on the number of top ranked wrestlers competing). It is traditional that on the final day the last three bouts of the tournament are between the top six ranked wrestlers, with the top two competing in the very final matchup, unless injuries during the tournament prevent this.

There are certain match-ups that are prohibited in regular tournament play. Wrestlers who are from the same training stable cannot compete against each other, nor can wrestlers who are brothers, even if they join different stables. The one exception to this rule being that training stable partners and brothers can face each other in a championship deciding playoff match.

Bout preparation

A top division wrestler will arrive at the stadium in the afternoon and enter the changing room. There are 'East' and 'West' rooms so competing wrestlers do not meet their opponents of the day prior to the match. The wrestler will change first into his kesho-mawashi, an ornate, embroidered silk 'apron', which he will wear during the ring entering ceremony, or dohyō-iri. There are four dohyō-iri on each day, two for jūryō and two for makuuchi division wrestlers. In each case there is a procession of those in the east changing room and one for those in the west. During the ceremony the wrestlers are introduced to the crowd one by one in ascending rank order and form a circle around the ring facing outwards. Once the highest ranked wrestler is introduced they turn inwards and perform a brief ritual before filing off and returning to their changing rooms. Yokozuna have a separate, more elaborate dohyō-iri; see yokozuna.

Once in the changing room the wrestlers change into their fighting mawashi and await their bouts. The wrestlers reenter the arena two bouts prior to their own and sit down at the side of the ring. There are no weight divisions in sumo, and considering the range of body weights in sumo, an individual wrestler can sometimes face an opponent twice his own weight. When it is their turn they will be called into the ring by a yobidashi (announcer) and they will mount the dohyō.[12]

On mounting the dohyō the wrestler performs a number of rituals derived from Shinto practice. Facing the audience, he claps his hands and then performs the leg-stomping shiko exercise to drive evil spirits from the dohyō as the gyōji, or referee, who will coordinate the bout announces the wrestlers' names once more. Stepping out of the ring into their corners, each wrestler is given a ladleful of water, the chikara-mizu ("power water"), with which he rinses out his mouth; and a paper tissue, the chikara-gami ("power paper"), to dry his lips. Then both step back into the ring, squat facing each other, clap their hands, then spread them wide (traditionally to show they have no weapons). Returning to their corners, they each pick up a handful of salt which they toss onto the ring to purify it.

Finally the wrestlers crouch down at the shikiri-sen, or starting lines, each trying to stare the other down. When both reach unspoken agreement, they spring from their crouch for the initial charge, the tachi-ai. In the upper divisions, they almost never charge on the first occasion. Instead, after staring they return to their corners for more mental preparation. More salt is thrown whenever they step back into the ring. This can happen a number of times (about three, or even more in the case of the highest ranks) until on the last occasion the referee informs them they must start the bout. The total length of time for this preparation is around four minutes for the top division wrestlers, but in the lower divisions they are expected to start more or less immediately.

A professional sumo bout

At the tachi-ai both wrestlers must jump up from the crouch simultaneously at the start of the bout, and the referee can restart the bout if this does not occur. Upon completion of the bout, the referee must immediately designate his decision by pointing his gunbai or war-fan towards the winning side. The referee's decision is not final and may be disputed by the five shimpan (judges) seated around the ring. If this happens they will meet in the center of the ring to hold a mono-ii (lit: a talk about things). After reaching a consensus they can uphold or reverse the referee's decision or order a rematch, known as a torinaoshi. The wrestlers will then return to their starting positions and bow to each other before retiring. A winning wrestler may receive additional prize money in envelopes from the referee if the matchup has been sponsored. If a yokozuna is defeated by a lower ranked wrestler, it is common and expected for audience members to throw their seat cushions into the ring (and onto the wrestlers), though this practice is technically prohibited.

In contrast to the time in bout preparation, bouts are typically very short, usually less than a minute, and often only a few seconds. Extremely rarely a bout can go on for many minutes (up to four minutes), in which case the referee may call a mizu-iri or "water break". The wrestlers are carefully separated, have a brief break and then return to the exact position they left off in. It is the referee's responsibility to reposition the wrestlers. If after four more minutes they are still deadlocked they may have a second break, after which they start from the very beginning. Further deadlock with no end of the bout in sight can lead to a draw (hikiwake), an extremely rare result in modern sumo. The last draw in the top division was in September 1974.[4]

The last day of the tournament is called senshuraku, which literally means the pleasure of a thousand autumns. This colorful name for the culmination of the tournament echoes the words of the playwright Zeami to represent the excitement of the decisive bouts and the celebration of the victor. The Emperor's Cup is presented to the wrestler who wins the top division (makuuchi) championship. Numerous other (mostly sponsored) prizes are also awarded to him. These prizes are often rather elaborate, ornate gifts, such as giant cups, decorative plates, and statuettes. Others are obviously commercial, such as one trophy shaped like a giant Coca-Cola bottle.

Promotion and relegation are determined by a wrestler's score over the 15 days. The term kachikoshi indicates a record having more wins than losses, as opposed to makekoshi, which indicates more losses than wins. In the top division, kachikoshi means a score of 8–7 or better, while makekoshi means a score of 7–8 or worse. A wrestler who achieves kachikoshi will almost always be promoted further up the ladder, the level of promotion being higher for better scores. See the makuuchi article for more details on promotion and relegation.

A top division wrestler who is not an ozeki or yokozuna and who finishes the tournament with kachikoshi is also eligible to be considered for one of the three sanshō prizes awarded for "technique" (ginōshō), "fighting spirit" (kantōshō), and for the defeating the most yokozuna and ozeki (shukunshō), sometimes referred to as "outstanding performance".

Please see the list of sumo tournament winners for an overview of the yusho winners since 1909.

TOMMY LIKES MARY

Life as a professional sumo wrestler

A sumo wrestler leads a highly regimented way of life. The Sumo Association prescribes the behavior of its wrestlers in a way that would be more commonly associated with life in a commune. For example, in the wake of a serious car accident involving a wrestler the Association banned wrestlers from driving their own cars. Breaking the rules can result in fines and/or suspension, not only for the offending wrestler, but also for his stablemaster.

On entering sumo, they are expected to grow their hair long to form a topknot, or chonmage, similar to the samurai hairstyles of the Edo Period. Furthermore they are expected to wear the chonmage and traditional Japanese dress when in public. Consequently, sumo wrestlers can be identified immediately when in public.

The type and quality of the dress depends on the wrestler's rank. Rikishi in jonidan and below are allowed to wear only a thin cotton robe called a yukata, even in winter. Furthermore they must wear a form of wooden sandals called geta when outside. These make a clip-clop sound as one walks in them. Wrestlers in the makushita and sandanme divisions can wear a form of traditional short overcoat over their yukata and are allowed to wear straw sandals, called zori. The sekitori can wear silk robes of their own choice and the quality of the garb is significantly improved. They also are expected to wear a more elaborate form of topknot called an oichi-o (lit. big ginkgo leaf) on formal occasions.

Similar distinctions are made in stable life. The junior rikishi must get up earliest, around 5 a.m., for training whereas the sekitori may start around 7 a.m. When the sekitori are training the junior rikishi may have chores to do, such as assisting in cooking the lunch, cleaning and preparing the bath, or holding a sekitori's towel for him for when he needs it. The ranking hierarchy is preserved for the order of precedence in bathing after training, and in eating lunch.

Rikishi are not normally allowed to eat breakfast and are expected to have a form of siesta after a large lunch. The most common type of lunch served is the traditional "sumo meal" of chankonabe which consists of a simmering stew cooked at table which contains various fish, meat, and vegetables. It is usually eaten with rice and washed down with beer. This regimen of no breakfast and a large lunch followed by a sleep helps rikishi put on weight so as to compete more effectively.

In the afternoon the junior rikishi will again usually have cleaning or other chores to do, while their sekitori counterparts may relax, or deal with work issues related to their fan clubs. Younger rikishi will also attend classes, although their education differs from the typical curriculum of their non-sumo peers. In the evening sekitori may go out with their sponsors while juniors stay at home in the stable, unless they are to accompany the stablemaster or a sekitori as his manservant (or tsukebito) when he is out (this is normally a more privileged role given to a rikishi who may be nearing sekitori status himself). Becoming a tsukebito (or personal assistant) for a senior member of the stable is a typical chore. A sekitori will have many tsukebito, with the most junior responsible for cleaning and other mundane tasks. Only the most senior tsukebito will accompany the sekitori when he goes out.

The sekitori also are given their own room in the stable or, may live in their own apartments. In contrast, the junior rikishi sleep in communal dormitories. Thus the world of the sumo wrestler is split broadly between the junior rikishi, who serve, and the sekitori, who are served. Life is especially harsh for new recruits, to whom the worst jobs tend to be allocated, and there is a high dropout rate at this stage.

The negative effects of the sumo lifestyle become dangerously apparent later in life. Sumo wrestlers have a life expectancy of between 60 and 65, more than 10 years shorter than the average Japanese male. They often develop diabetes and high blood pressure, and are prone to heart attacks. The excessive intake of alcohol can lead to liver problems and the stress on their joints can cause arthritis. Recently, the standards of weight gain are becoming less strict, in an effort to improve the overall health of the wrestlers.[13][14] The average height of sumo wrestlers is around 178 cm (5' 10").

Salary and payment

As of 2006, the monthly salary figures for makuuchi (in Japanese Yen) were:[15]

- yokozuna: 2,820,000 or about $24,500 USD

- ōzeki: 2,347,000 or about $20,400 USD

- sanyaku: 1,693,000 or about $14,800 USD

- maegashira: 1,309,000 or about $11,300 USD

- jūryō: 1,036,000 or about $9,000 USD

Wrestlers lower than Juryo, who are considered to be trainees, do not receive a salary, but only a fairly small allowance.

In addition to the basic salary, sekitori wrestlers also receive additional bonus income, called mochikyukin, six times a year (once every tournament, or basho) based on the cumulative performance in their career to date. This bonus increases every time that the rikishi scores a kachikoshi (with larger kachikoshi giving larger raises.) Special increases in this bonus are also awarded for winning the top division championship (with an extra large increase for a "perfect" championship victory with no losses), and also for scoring a kinboshi (an upset of a yokozuna by a maegashira).

sanyaku wrestlers also receive a relatively small additional tournament allowance, depending on their rank, and yokozuna receive an additional allowance every second tournament, associated with the making of a new tsuna.

There is also prize money for the winner of each divisional championship, which increases from 100,000 yen for a jonokuchi victory up to 10,000,000 yen for winning the top division. For wrestlers in the top division giving an exceptional performance in the eyes of a judging panel there are also three special prizes (the sansho) which are worth 2,000,000 yen each.[16]

Individual top division matches can also be sponsored by companies. In such cases the winner of the bout typically receives around 30,000 yen net per sponsor (out of the sponsors contribution of 60,000 yen -- much of the remainder goes in paying the wrestler's tax on the prize). These bout prizes are called kenshokin. For bouts involving yokozuna and ozeki the number of sponsors of the matchup can be quite large, whereas for lower ranked matchups there may be no bout sponsors at all unless one of the wrestlers is particularly popular, or unless a company has a policy of sponsoring all his matchups. No bout prize money is awarded for a bout decided by a fusensho (forfeit victory).

Sumo and Shinto

Shinto has historically been used as a means for Japanese nationalism and ethnic identity, especially prior to the end of World War II. It has served to symbolize and provide a sense of belonging, to identify and unify the Japanese people culturally, and to serve as a barrier demarcating the Japanese from other peoples, providing them with a sense of cultural uniqueness. In its association with Shinto, sumo has also been seen as a bulwark of Japanese tradition.[17]

Shinto ritual pervades every aspect of sumo. Before a tournament, two of the gyōji functioning as Shinto priests enact a ritual to consecrate the newly-constructed dohyō, and various Shinto rituals are associated even with the practice dohyō at heya. Both the dohyō-iri, or ring-entering ceremonies performed by the top two divisions before the start of their wrestling day, and in the rituals performed by both combatants immediately before a bout, are derived from Shinto.[18] It retains other Shinto associations as well. The yokozuna's ring-entering ceremony is regarded as a purification ritual in its own right, and is occasionally performed at Shinto shrines for this purpose. Every newly-promoted yokozuna performs his first ring-entering ceremony at the Meiji Shrine in Tokyo.

Controversies

Match-fixing

Due to the amount of money changing hands depending on rank, and prize money, there have been accusations of yaocho (corruption, bout-fixing) in sumo from time to time. In 2002, Steven Levitt and Mark Duggan published a paper using econometrics in order to prove that corruption in sumo exists.[19] Popularized in Levitt's book Freakonomics, the study found that 70% of wrestlers with 7–7 records on the final day of the tournament (i.e., seven wins and seven losses, and one fight to go) won. The percentage was found to rise the more times the two wrestlers had met, and decrease when the wrestler was due to retire. The study, which was detailed in , found the 7–7 wrestler wins around 80% of the time when statistics suggest they have a probability of winning only 48.7% of the time against their opponent. The authors conclude that those who already have 8 wins collude with those who are 7–7 and let them win, since they have already secured their ranking.

A possible counter-argument to the Freakonomics conclusion is that a 7–7 rikishi is highly motivated to win his last match to gain promotion, rather than demotion, while the 8–6 rikishi has already guaranteed his promotion, so is not as motivated. The authors revealed a more damning statistic, however. According to their research, the next tournament in which the two wrestlers met, there was a significant advantage to the 8–6 wrestler over the 7–7, regardless of the performance of either wrestler. The 7–7 wrestler would win only 40% percent of the rematches with the 8–6 wrestler. The authors suggest that winning 80% in the first match and then only 40% in the rematch (and back to the expected 50% in subsequent matches) between the same wrestlers suggest a rigging of the bouts. Additionally, the authors find that after allegations of rigging by the media, 7–7 wrestlers won only 50% of their matches against 8–6 wrestlers instead of 80%.

Gender Issues

Other ongoing criticisms towards sumo revolve around its general exclusion of women from competition and ceremonies. Women are not allowed to enter or touch the sumo wrestling ring (dohyō), as this is traditionally seen by Shintoists to be a violation of the purity of the dohyō.[20] The female Governor of Osaka in the late 1990s, Fusae Ohta, when called upon to present the Governor's Prize to the champion of the annual Osaka tournament, was required to do so on the walkway beside the ring or send a male representative in her place. She repeatedly challenged the Sumo Association's policy by requesting to be allowed to fulfill her traditional role as Governor. Her requests were repeatedly rejected until she stepped down from office in 2007. Additionally, female-based sumo, even though it is popular in areas of the West, is not considered to be authentic by most Japanese and is prohibited from taking place in anything but amateur settings.[21]

The view of those who criticize this continuing "men-only" policy in sumo is that it is discriminatory and oppressive.[20] In general, women in the Sumo world are only expected to be supportive wives of rikishi, and, in the case that their husband has become a stable master, a surrogate mother for all of his disciples.[3] The view of the Sumo Association is that this is a tradition that has been firmly maintained through the centuries, so it would be a dishonor to all of their ancestors to change it.[20]

The only noted case of a woman stepping onto a dohyō in recent times during a nationally televised tournament occurred on September 19, 2007. On this day the woman in question approached the dohyō carrying several large sheets of paper only to be stopped by a female security guard. After the woman pushed her aside, she managed to climb onto the dohyō before popular rikishi Takamisakari, ring-side judge Nishikido, and attendants managed to pull her away. When questioned the woman appeared incoherent.[22]

Hazing

It has been well-known and accepted for many years that sumo stables engage in the systematic hazing and physical punishment of young disciples in order to "toughen them up".[3] Stable masters have often been proud to show to the media how they frequently use a shinai to beat up on those who make mistakes, and elder rikishi are often put in charge of bullying younger ones to keep them in line, for instance, by making them hold heavy objects for long periods of time.[3] However, this system of hazing was widely criticized in late 2007 when it came to light that a 17 year-old-sumo trainee named Takashi Saito from the Tokitsukaze stable had died after a serious bullying incident involving his stablemaster Futatsuryu Junichi hitting him in the head with a large beer bottle and fellow rikishi being subsequently ordered to physically abuse him further. The (now ex-)stablemaster and three other wrestlers who were involved were arrested in February 2008, after which Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda demanded the Sumo Association take steps to ensure such an incident never happens again.[23]

Memorabilia

As with many sports, there are a wide variety of souvenirs and memorabilia that fans may acquire. Fans purchasing box seats or front row seats usually purchase the tickets through so-called tea houses, which provide sumo related items in a package that includes the purchase of the ticket. This sort of memorabilia can also be purchased separately. Plates, and cups with sumo related themes are a common item. One of the more unusual items that can be purchased is the tegata (lit. hand shape) of the wrestlers of whom one is a fan—the sumo version of an autograph. Tegata consist of a hand print of the wrestler using black or red ink accompanied by his fighting name written in calligraphic style by the wrestler himself. Original tegata can be quite expensive, but printed copies of the most popular wrestlers can be obtained very inexpensively. Only wrestlers in the top two jūryō and makuuchi divisions are permitted to make them. Another popular collectible is a copy of the banzuke for a tournament. A banzuke is a document that has been meticulously handwritten in calligraphic script and lists every wrestler who participates in a tournament in order of rank.

Sumo in contrast to other Eastern martial arts

Sumo, while considered a martial art, diverges from the typical Eastern style both at the surface and at its heart. Whereas most martial arts award promotions through time and practice, sumo ranks can be gained and lost every two months in the official tournaments. Conversely, in more common Japanese martial arts (such as karate), ranks are gained after passing a single test, and practitioners of karate are not normally demoted, even after repeated poor performances at tournaments. This divergence from other martial arts creates a high-pressure, high-intensity environment for sumo wrestlers. All the benefits that sekitori wrestlers receive can be taken from them if they fail to maintain a high level of achievement in each official tournament.

Furthermore, sumo does not provide any means of achievement besides the official tournaments. Rank is determined solely by winning records during an official tournament. On the other hand, in many other Eastern martial arts, competitors can display their skill by performing standard routines, called kata or forms, to receive recognition. Thus, sumo wrestlers are very specialized fighters who train to win their bouts using good technique, as this is their only means of gaining better privileges in their stables and higher salaries.

Amateur sumo

Sumo is also an amateur sport, with participants in college, high school and grade school in Japan. In addition to college and school tournaments, there are also open amateur tournaments. The sport at this level is stripped of most of the ceremony. The most successful amateur wrestlers in Japan (usually college champions) can be allowed to enter professional sumo at makushita (third division) rather than from the very bottom of the ladder. This rank is called makushita tsukedashi, and is currently makushita 10. Many of the current top division wrestlers entered professional sumo by this route. All entry by amateur athletes into the professional ranks is subject to them being young enough (23 or under) to satisfy the entry requirements.

The sport is very popular among young children, especially those who are considered to be overweight, or whose father also participates in sumo. It is generally seen as an advantage if a child is obese, their oversized body mass allows them to better stabilize themselves and take down their opponent.

There is also an International Sumo Federation, which encourages the sport's development worldwide, including holding international championships. A key aim of the federation is to have Sumo recognized as an Olympic sport. Accordingly, amateur tournaments are divided into weight classes (men: Lightweight up to 187 lb (85 kg) [85 kg], Middleweight up to 253 lb (115 kg) [115 kg], Heavyweight 253+ lb [115+ kg] and Open Weight [unrestricted entry]), and include competitions for female wrestlers (Lightweight up to 143 lb (65 kg) [65 kg], Middleweight up to 176 lb (80 kg) [80 kg], Heavyweight 176+ lb [80+ kg] and Open Weight).

Amateur Sumo clubs are gaining in popularity in the United States, with competitions regularly being held in major cities across the country. The sport has long been popular on the West Coast and in Hawai'i, where it has played a part in the festivals of the Japanese ethnic communities. Now, however, the sport has grown beyond the sphere of Japanese diaspora and athletes come from a variety of ethnic, cultural and sporting backgrounds.

Amateur sumo is particularly strong in Europe. Many athletes come to the sport from a background in judo, freestyle wrestling, or other grappling sports such as Sambo. Some Eastern European athletes have been successful enough to be scouted into professional sumo in Japan, much like their Japanese amateur counterparts. The most proficient of these to date is the Bulgarian Kotooshu, who is the highest ranking foreign wrestler who was formerly an amateur sumo athlete.

See also

- Glossary of sumo terms

- List of active sumo wrestlers

- List of past sumo wrestlers

- List of sumo beya

- List of sumo records

- List of sumo tournament winners

- List of yokozuna

- E. Honda

References

- Benjamin, David (1991). The Joy of Sumo: A Fan's Notes. Rutland, Vermont, U.S.A. & Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 0-8048-1679-4.

- Schilling, Mark (1994). Sumo: A Fan's Guide. Tokyo, Japan: The Japan Times, Ltd.. ISBN 4-7890-0725-1.

- Shapiro, David (1995). Sumo: A Pocket Guide. Rutland, Vermont, U.S.A. & Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 0-8048-2014-7.

- Tablero, Fco. Javier (2002). Parentesco y organización del sumo en Japón. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. ISBN 84-8466-257-8.

Notes

- ↑ Young, Robert W. (2007). "History and Overview of the Martial Arts". USADOJO.COM. Retrieved on 2007-06-29.

- ↑ "Rules of Sumo". Beginner's Guide of Sumo. Japan Sumo Association. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Hall, Mina (1997). The Big Book of Sumo: History, Practice, Ritual, Fight. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-880656-28-0.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Sharnoff, Lorna (1993). Grand Sumo. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0283-x.

- ↑ "Sumo Beya Guide". Japan Sumo Association. Retrieved on 2007-07-08.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Banzuke". Beginner's Guide of Sumo. Japan Sumo Association. Retrieved on 2007-06-27.

- ↑ "Foreigners in Sumo". dichne.com. Retrieved on 2007-06-27.

- ↑ McCurry, Justin (3 July 2007). "Last of the Sumo - Japanese youth turn their backs on gruelling sport of emperors". The Guardian. Retrieved on 2007-07-08.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hiroyuki Tai (2005-11-25). "Foreign sumo aspirants' numbers kept in check by stable quota policy". japantimes.co.jp. Retrieved on 2007-09-20.

- ↑ Buckton, Mark (2007-01-23). "Numbers break records, character creates legends". Japan Times. Retrieved on 2008-06-12.

- ↑ An exception to this rule occurred when Hirohito, the former Emperor of Japan, died on Saturday, January 7, 1989. The tournament which was to start on the following day was postponed; starting on Monday, January 9 and finishing on Monday, January 24.

- ↑ Schuler, Nicolas; Macan, Jelena (trans.) (April 2004). "Detailed description of a sumo bout". Le Monde de Sumo N°3. Retrieved on 2007-08-03.

- ↑ "Becoming a Sumo Wrestler". Sumo East and West. Discovery Channel. Retrieved on 2005-11-18.

- ↑ "United Nations Statistics Division - Demographic and Social Statistics". Retrieved on 2005-11-18.

- ↑ "Rikishi Salaries" (in Japanese). Retrieved on 2007-10-29.

- ↑ "Sumo Questions". Retrieved on 2005-11-18.

- ↑ Reader, Ian (December 1989). "Sumo: The Recent History of an Ethical Model for Japanese Society". International Journal of the History of Sport 6 (3): 285–298. doi:.

- ↑ "Sumo Ceremonies". Beginner's Guide of Sumo. Japan Sumo Association. Retrieved on 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Duggan, Mark; Levitt, Steven D. journal = The American Economic Review. Winning isn't Everything: Corruption in Sumo Wrestling. 92. pp. 1594-1605. http://pricetheory.uchicago.edu/levitt/Papers/DugganLevitt2002.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-11-20.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "ReDotPop Sumo". PopMatters (2000-04-05). Retrieved on 2008-03-12.

- ↑ "An Inside Look at Shin Sumo". Eastwest Lifestyle (2005-June). Retrieved on 2008-03-12.

- ↑ "女性が土俵乱入、高見盛ら取り押さえ". Nikkan Sports (2007-09-28). Retrieved on 2008-03-30.

- ↑ "Japan PM angry over Sumo death". BBC (2008-02-08). Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

External links

- Nihon Sumo Kyokai Official Grand Sumo Home Page

- The Sumo Forum

- Banzuke.com

- Sumo FAQ

- Sumo introduction including biographies and autographs

- Searchable Sumo Database

- Szumo.hu

- Sumo Fan Magazine

- Sumo News and Analysis

- Info-Sumo.net

- Mainichi Daily News: Sports Sumo News

- History of Women's Sumo

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||