Subduction

In geology, a subduction zone is an area on Earth where two tectonic plates meet and move towards one another, with one sliding underneath the other and moving down into the mantle, at rates typically measured in centimeters per year. An oceanic plate ordinarily slides underneath a continental plate or another oceanic plate; this often creates an orogenic zone or volcanic arc subject to many earthquakes. In a sense, subduction zones are the opposite of divergent boundaries, areas where material rises up from the mantle and plates are moving apart.

Contents |

General description

Subduction zones mark sites of convective downwelling of the Earth's lithosphere (the crust plus the strong portion of the upper mantle). Subduction zones exist at convergent plate boundaries where one plate of oceanic lithosphere converges with another plate and sinks below it to depth of approximately 100 km. At that depth the peridotite of the oceanic slab is converted to eclogite, the density of the edge of the oceanic lithosphere increases and it sinks into the mantle. It is at subduction zones that the Earth's lithosphere, oceanic crust, sedimentary layers, and trapped water are recycled into the deep mantle. Earth is the only planet where subduction is known to occur. Without subduction, plate tectonics could not exist.

Subduction results from the difference in density between lithosphere and underlying asthenosphere. Where, very rarely, lithosphere is denser than asthenospheric mantle, it can easily sink back into the mantle at a subduction zone; however, subduction is resisted where lithosphere is less dense than underlying asthenosphere. Whether or not lithosphere is denser than underlying asthenosphere depends on the nature of the associated crust. Crust is always less dense than asthenosphere or lithospheric mantle and continental lithosphere is always less dense than oceanic lithosphere. Exceptionally, the presence of the large areas of flood basalt that are called large igneous provinces (LIPs), which result in extreme thickening of the oceanic crust, can cause some sections of older oceanic lithosphere to be too buoyant to subduct. Where lithosphere on the downgoing plate is too buoyant to subduct, a collision occurs, hence the adage "Subduction leads to orogeny".

Theory on origin

There have been some recent theories on the beginnings of subduction and Plate tectonics generally. A recent paper by V.L. Hansen in Geology presented a hypothesis that mantle upwelling and similar thermal processes combined with an impact from an extraterrestrial source would give the early earth the discontinuities in the crust for the subduction of the denser material underneath lighter material.[1]

Associated volcanic activity

Volcanoes that occur above subduction zones, such as Mount St. Helens and Mount Fuji, often occur in arcuate chains, hence the term volcanic arc or island arc. Not all "volcanic arcs" are arced: trenches and arcs are often linear.

The magmatism associated with the volcanic arc occurs 100-300 km away from the trench. However, a relationship has been found, which relates volcanic arc location to depth of the subducted crust as defined by the Wadati-Benioff zone. Studies of many volcanic arcs around the world have revealed that volcanic arcs tend to form at a location where the subducted slab has reached a depth of about 100 km. This has interesting implications for the mechanism that causes the magmatism at these arcs. Arcs produce about 25% of the total volume of magma produced each year on Earth (~30-35 km³), much less than the volume produced at mid-ocean ridges. Nevertheless, arc volcanism has the greatest impact on humans, because many arc volcanoes lie above sea level and erupt violently. Aerosols injected into the stratosphere during violent eruptions can cause rapid cooling of the Earth's climate.

The absence of volcanism in the Norte Chico region of Chile is believed to be a result of a flat-slab subduction caused by the Juan Fernández Rise.

Earthquakes and tsunamis

Subduction zones are also notorious for producing devastating earthquakes because of the intense geological activity. The introduction of cold oceanic crust into the mantle depresses the local geothermal gradient and causes a larger portion of the earth to deform in a more brittle fashion than it would in a normal geothermal gradient setting. Because earthquakes can only occur when a rock is deforming in a brittle fashion, subduction zones have the potential to create very large earthquakes. If this earthquake occurs under the ocean it has the potential to create tsunamis, such as the earthquake caused by subduction of the Indo-Australian Plate under the Eurasian Plate on December 26, 2004, that devastated the areas around the Indian Ocean. Small tremors that create tiny, unnoticeable tsunamis happen all the time because of the dynamics of the earth.

Subduction zones are associated with the deepest earthquakes on the planet. Earthquakes are generally restricted to the shallow, brittle parts of the crust, generally at depths of less than 20 km. However, in subduction zones, earthquakes occur at depths as great as 700 km. These earthquakes define inclined zones of seismicity known as Wadati-Benioff zones (after the scientists who discovered them), which outline the descending lithosphere. Seismic tomography has helped outline subducted lithosphere in regions where there are no earthquakes. Some subducted slabs seem not to be able to penetrate the major discontinuity in the mantle that lies at a depth of about 670 km, whereas other subducted oceanic plates can penetrate all the way to the core-mantle boundary. The great seismic discontinuities in the mantle - at 410 and 670 km depth - are disrupted by the descent of cold slabs in deep subduction zones.

Importance

Subduction zones are important for several reasons:

- Subduction Zone Physics: Sinking of mantle lithosphere is the strongest force (but not the only one) needed to drive plate motion and is the dominant mode of mantle convection.

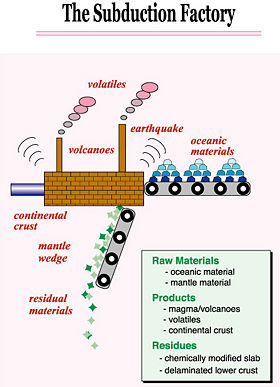

- Subduction Zone Chemistry: The cold material sinking in subduction zones releases water into the overlying mantle, causing mantle melting and fractionating elements (buffering) between surface and deep mantle reservoirs, producing island arcs and continental crust.

- Subduction Zone Biology: Because subduction zones are the coldest parts of the Earth's interior and life cannot exist at temperatures >150°C, subduction zones are almost certainly associated with the deepest (highest pressure) biosphere.

- Subduction zones mix subducted sediments, oceanic crust, and mantle lithosphere and mix this with mantle from the overriding plate to produce fluids, calc-alkaline series melts, ore deposits, and continental crust.

Subduction zones have also being considered as possible disposal sites for nuclear waste, where the action would carry the material into the planetary mantle, safely away from any possible influence on humanity or the surface environment, but this method of disposal is currently banned by international agreement[2].

See also

- Plate tectonics

- List of tectonic plate interactions

- Back-arc basin

- Oceanic rift

- Oceanic trench

- Obduction

- Orogeny

References

- ↑ Vicki L. Hansen, Univ. of Minnesota-Duluth. "Subduction origin on early Earth: A hypothesis" Geology, December 2007; v.35; no.12; pg. 1059 - 1062

- ↑ World Nuclear Association

- Stern, R.J., 2002, Subduction zones: Reviews of Geophysics, v. 40, 1012, doi: 10.1029/2001RG000108.

- Stern, R.J., 1998. A Subduction Primer for Instructors of Introductory Geology Courses and Authors of Introductory Geology Textbooks: J. Geoscience Education, 46, 221-228.

- Tatsumi, Y. 2005. The Subduction Factory: How it operates on Earth. GSA Today, v. 15, No. 7, 4-10.