Double bass

|

|

| Classification | String instrument (bowed or plucked) |

|---|---|

| Playing range | |

|

|

| Other names | Bass, String Bass, Upright Bass, Standup Bass, Acoustic Bass, Contrabass, Contrabass Violin, Bass Violin, Bass Fiddle, Bull Fiddle, Contrabbasso |

| Related instruments | *Viol |

| Musicians | *List of double bassists |

The double bass or contrabass is the largest and lowest-pitched bowed string instrument used in the modern symphony orchestra. It is a standard member of the string section of the symphony orchestra [1] and smaller string ensembles [2] in Western classical music. In addition, it is used in other genres such as jazz, 1950s-style blues and rock and roll, rockabilly/psychobilly, bluegrass, and tango.

Double basses are constructed from several types of wood, including maple for the back, spruce for the top, and ebony for the fingerboard. It is uncertain whether the instrument is a descendant of the viola da gamba or from the violin, but it is traditionally considered to be a member of the violin family. While the double bass has features which are similar to those found on other violin family instruments, it also has features which may be derived from the viols.

Like many other string instruments, the double bass is played either with a bow (arco) or by plucking the strings (pizzicato). In orchestral repertoire and tango music, both bowing and plucking styles are used. In jazz music, the bass is mostly plucked, except for some solos which are performed with the bow. In most other genres, such as blues and rockabilly, the bass is plucked.

Contents |

History

The double bass is generally regarded as the modern descendant of the string family of instruments, a family which originated in Europe in the 15th century, and as such it has been described as a "bass violin."[3] Before the 20th century many double basses had only three strings, in contrast to the five to six strings typical of instruments in the string family or the four strings of instruments in the violin family. Some existing instruments, such as those by Gasparo da Salò, were converted from sixteenth-century six-string contrabass violoni.[4]

The double bass's proportions are dissimilar to those of the violin and cello; for example, it is deeper (the distance from top to back is proportionally much greater than the violin). In addition, while the violin has bulging shoulders, most double basses have shoulders carved with a more acute slope, like members of the viola da gamba family. Many very old double basses have had their shoulders cut or sloped to aid playing with modern techniques. Before these modifications, the design of their shoulders was closer to instruments of the violin family.

The double bass is the only modern bowed string instrument that is tuned in fourths (like viols), rather than fifths (see Tuning, below). The issue of the instrument's exact lineage is still a matter of some debate, and the supposition that the double bass is a direct descendant of the viola da gamba family is one that has not been entirely resolved.

In his A New History of the Double Bass, Paul Brun asserts, with many references, that the double bass has origins as the true bass of the violin family. He states that, while the exterior of the double bass may resemble the viola da gamba, the internal construction of the double bass is nearly identical to that of other instruments in the violin family, and is very different from the internal structure of viols.[5]

Terminology

A person who plays this instrument is called a bassist, double bassist, double bass player, contrabassist, contrabass player, or bass player. There are several theories behind the instrument's standard English name, double bass. Some music historians argue that it is a reference to the older notation of naming notes where notes below C3 were notated with two of the letter of the note name twice. (Such as, E2 would be EE, or Double E). This is similar to the term BBb Flat Tuba. Despite the prevalence of a folk etymology which purports that the name is a reference to fact that the bass is larger than the cello, the term "double bass" is not related to its physical size. The name may derive from its alleged viol family heritage, in that it is tuned lower than the standard bass viola da gamba. The name also refers to the fact that the sounding pitch of the double bass is an octave below the bass clef.

Other terms for the instrument among classical performers are contrabass (which comes from the instrument's Italian name, contrabasso), string bass, or bass. Jazz musicians often call it the upright bass, standup bass, or acoustic bass to distinguish it from the electric bass guitar. Especially when used in folk and bluegrass music, the instrument can also be referred to as a bass fiddle or bass violin (or more rarely as doghouse bass or bull fiddle). Other colourful nicknames are found in other languages; in Hungarian, for instance, the double bass is sometimes called nagy bőgő, which roughly translates as "big crier", referring to its large voice.

Design

In general there are two major approaches to the design outline shape of the double bass, these being the violin form, and the viol da gamba form. A third less common design called the busetto shape (and very rarely the guitar or pear shape) can also be found. The back of the instrument can vary from being a round, carved back similar to that of the violin, or a flat and angled back similar to the viol family.

The double bass features many parts that are similar to members of the violin family including a bridge, f-holes, a tailpiece, a scroll and a sound post. Unlike the rest of the violin family, the double bass still reflects influence and can be considered partly derived from the viol family of instruments, in particular the violone, the bass member of the viol family.

The double bass also differs from members of the violin family in that the shoulders are (sometimes) sloped, the back is often angled (both to allow easier access to the instrument, particularly in the upper range), and machine tuners are always fitted. Lack of standardization in design means that one double bass can sound and look very different from another. To see some of the variations and construction approaches discussed above visit the websites quoted below.

Construction

The double bass is closest in construction to violins, but has some notable similarities to the violone (literally "large viol"), the largest and lowest member of the viola da gamba family. Unlike the violone, however, the fingerboard of the double bass is unfretted, and the double bass has fewer strings (the violone, like most viols, generally had six strings, although some specimens had five or four).

An important distinction between the double bass and other members of the violin family is the construction of the pegbox. While the violin, viola, and cello all use friction pegs for gross tuning adjustments, the double bass has metal machine heads. The key on the tuning machine turns a metal "worm" which drives a worm gear that winds the string. While this development makes fine tuners unnecessary, a very small number of bassists use them nevertheless. At the base of the double bass is a metal rod with a spiked end called the endpin, which rests on the floor. This endpin is generally more robust than that of a cello, because of the greater mass of the double bass.

The soundpost and bass bar are components of the internal construction. The materials most often used are maple (back, neck, ribs), spruce (top), and ebony (fingerboard, tailpiece). Exceptions to this include less-expensive basses which have laminated (plywood) tops, backs, and ribs, and some newer mid-range basses made of willow. These basses are resistant to changes in heat and humidity, which can cause cracks in spruce tops. Plywood laminate basses, which are used in music schools, youth orchestras, and in bluegrass, are very resistant to humidity and heat, as well to the physical abuse they are apt to encounter in a school environment.

All the parts of a double bass are glued together, except the soundpost, bridge and tailpiece, which are held in place by string tension, although the soundpost will usually remain in place when the instrument's strings are loosened or removed. The metal tuning machines are attached to the sides of the pegbox with metal screws. While tuning mechanisms generally differ from the higher-pitched orchestral stringed instruments, some basses have non-functional, ornamental tuning pegs projecting from the side of the pegbox, in imitation of the tuning pegs on a cello or violin.

Strings

Prior to the mid-20th century, double bass strings were usually made of gut, but since that time, steel strings have largely replaced gut strings, because steel strings hold their pitch better and yield more volume when played with the bow.[6] Gut strings are also more vulnerable to changes of humidity and temperature, and they break much more easily than steel strings. Gut strings are nowadays mostly used by bassists who perform in baroque ensembles, rockabilly bands, traditional blues bands, and bluegrass bands [7] Gut strings create the dark, "thumpy" sound heard on 1940s and 1950s recordings. The late Jeff Sarli, a blues upright bassist, stated that "[s]tarting in the 1950s, they began to reset the necks on basses for steel strings", and double bass players switched from gut strings to steel strings.[8] Rockabilly and bluegrass bassists also prefer gut because it is much easier to perform the "slapping" upright bass style (in which the strings are percussively slapped and clicked against the fingerboard) with gut strings than with steel strings. (For more information on slapping, see the sections below on Modern playing styles, Double bass in bluegrass music, Double bass in jazz, and Double bass in popular music).

The change from gut to steel has also affected the instrument's playing technique over the last hundred years, because playing with steel strings allows the strings to be set up closer to the fingerboard, and, additionally, steel strings can be played in higher positions on the lower strings and still produce clear tone. The classic 19th century Franz Simandl method does not utilize the low E string in higher positions because with older gut strings set up high over the fingerboard, the tone was not clear in these higher positions. However, with modern steel strings, bassists can play with clear tone in higher positions on the low E and A strings, particularly when modern lighter-gauge, lower-tension steel strings (e.g., Corelli/Savarez strings) are used.

Bows

The double bass bow comes in two distinct forms (shown below). The "French" or "overhand" bow is similar in shape and implementation to the bow used on the other members of the orchestral string instrument family, while the "German" or "Butler" bow is typically broader and shorter, and is held in a "hand shake" position.

These two bows provide for different ways of moving the arm and distributing force on the strings. Proponents of the French bow argue that it is more maneuverable, due to the angle at which the player holds the bow. Advocates of the German bow claim that it allows the player to apply more arm weight on the strings. The differences between the two, however, are minute for a proficient player, and both bows are used by modern players in major orchestras.

German bow

The German bow (sometimes called Dragonetti bow) is the older of the two designs. The design of the bow and the manner of holding it are descended from the older viol family of instruments. With older viols, before screw threads were used to tighten the bow, players held the bow with two fingers between the stick and the hair to maintain tension of the hair. Proponents of the use of German bow claim that the German bow is easier to use for light bow strokes as staccato, spiccato, and detaché.

In comparison with the French bow, the German bow has a taller frog, and it is held with the palm angled upwards, as is done for the upright members of the viol family. When held in correct manner, the thumb rests on the side of the stick. The index finger balances the bow at the point where the frog meets the stick. The index finger is also used to apply an upward torque to the frog when tilting the bow. The little finger (or "pinky") supports the frog from underneath, while the ring finger and middle finger are used to apply the force to move the bow across the strings.

French bow

The French bow was not widely popular until its adoption by 19th-century virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. This style is more similar to the traditional bows of the smaller string family instruments. It is held as if the hand is resting by the side of the performer with the palm facing toward the bass. The thumb rests on the shaft of the bow, next to the frog while the other fingers drape on the other side of the bow. Various styles dictate the curve of the fingers and thumb, as do the style of piece; a more pronounced curve and lighter hold on the bow is used for virtuosic or more delicate pieces, while a flatter curve and sturdier grip on the bow provides more power for loud orchestral passages.

Bow construction and materials

Double bass bows vary in length, ranging from 60 cm (24") to 75 cm (30").Pernambuco, also known as Brazilwood, is regarded as an excellent quality stick material, but due to its scarcity and expense, other materials are increasingly being used. Less expensive student bows may be constructed of solid fiberglass, or of less valuable varieties of brazilwood. Snakewood and carbon fiber are also used in bows of a variety of different qualities. The frog of the double bass bow is usually made out of ebony, although Snakewood and buffalo horn are used by some luthiers. The wire wrapping is gold or silver in many quality bows, and the hair is usually horsehair. Some of the lowest-quality student bows are made from molded plastic and synthetic fiberglass "hair".

The double bass bow is strung with either white or black horsehair, or a combination of the two (known as "salt and pepper"), as opposed to the customary white horsehair used on the bows of other string instruments. Some bassists argue that the slightly rougher black hair "grabs" the heavier, lower strings better. As well, some bassists and luthiers believe that it is easier to produce a smoother sound with the white variety. Red hair is also used by some bassists.

Rosin

String players apply rosin to the hair of their bow so that the hair will "grip" the string and make it vibrate. Double bass rosin is generally softer and stickier than violin rosin to allow the hair to grab the thicker strings better, but players use a wide variety of rosins that vary from quite hard (like violin rosin) to quite soft, depending on the weather, the humidity, and the preference of the player. The amount used generally depends on the type of music being performed as well as the personal preferences of the player. Bassists may apply more rosin in works for large orchestra (e.g., Brahms symphonies) than for delicate chamber works. Some brands of rosin, such as Pop's double bass rosin, are softer and more prone to melting in hot weather. Other brands, such as Carlsson or Nyman Harts double bass rosin, are harder and less prone to melting.

Pitch

The lowest note of a double bass is an E1 (on standard four-string basses) at approximately 41 Hz or a B0 (when five strings are used) at approximately 31 Hz. This is slightly above the lowest frequency that the average human ear can perceive as a distinctive pitch--about 20 Hz. The highest notes are almost down at the bridge. Five string instruments either use the additional string tuned to a low B below the E string, or to a C above the G string. In many double bass concertos harmonic tones are used. The use of natural harmonics (a technique often used by Giovanni Bottesini) and sometimes even artificial harmonics, where the thumb stops the note and the octave or other harmonic is activated by lightly touching the string at the relative node point, extend the double bass' range considerably.

The double bass parts from most orchestral music rarely exceed three octaves. However, a virtuoso solo player could cover five or six octaves in solo bass repertoire, using natural and artificial harmonics. Since the range of the double bass lies largely below the standard bass clef, it is notated an octave higher (hence sounding an octave lower than written). This transposition applies even when reading the tenor and treble clef, which are used to avoid excessive ledger lines when notating the instrument's upper range.

Tuning

The double bass is generally tuned in fourths, in contrast to the other members of the orchestral string family, which are tuned in fifths. This avoids a too-long finger stretch (known among players as an "extension"). Modern double basses are usually tuned, low to high, E-A-D-G, one octave lower than a cello.

Throughout classical repertoire, there are notes that fall below the range of a standard double bass. Notes below low E appear regularly in double bass parts in the Baroque and Classical eras, when the double bass was typically doubling the cello part an octave below. In the Romantic era and the 20th-century, composers such as Mahler, Beethoven, and Prokofiev also requested notes below the low E. There are two common methods for making these notes available to the player. Major European orchestras generally use basses with a fifth string, tuned to B three octaves and a semitone below middle C.[9] Players with standard double basses (E-A-D-G) typically play the notes below "E" an octave higher.

In the United States, Canada and United Kingdom, most professional orchestral players use four-string double basses with a "C extension" which extends the lowest string down as far as low C, an octave below the lowest note on the cello (more rarely, this string may be tuned to a low B). The extension is an extra section of fingerboard mounted up over the head of the bass. There are several varieties of extensions. In the simplest version, there are no mechanical aids attached to the fingerboard extension. To play the extension notes, the player reaches back over the pegs to press the string to the fingerboard. The simplest type of mechanical aid is the use of wooden "fingers" that can be closed to press the string down and fret the C#, D, Eb, or E notes. This system is particularly useful for basslines that have a repeating pedal point such as a low D, because once the note is locked in place with the mechanical "finger", the lowest string then sounds a different note when it is played "open" (e.g., a low D).

The most complicated mechanical aid for use with extensions are mechanical lever systems nicknamed "machines". These lever systems, which superficially resemble the mechanisms of reed instruments such as the bassoon, include levers mounted beside the regular fingerboard (near the nut, on the "E" string side) which remotely activate metal "fingers" on the extension fingerboard. The most expensive metal lever systems also give the player the ability to "lock" down notes on the extension fingerboard, as with the wooden "finger" system. One criticism of these devices is that they may lead to unwanted metallic clicking noises.

A small number of bass players tune their strings in fifths, like a cello but an octave lower (C-G-D-A low to high). This tuning was used by the jazz player Red Mitchell and is increasingly used by classical players, notably the Canadian bassist Joel Quarrington. In classical solo playing the double bass is usually tuned a whole tone higher (F♯-B-E-A). This higher tuning is called "solo tuning," whereas the regular tuning is known as "orchestral tuning." String tension differs so much between solo and orchestral tuning that a different set of strings is often employed that has a lighter gauge. Strings are always labelled for either solo or orchestral tuning, and published solo music is arranged for either solo or orchestral tuning. Some popular solos and concerti, such as the Koussevitsky Concerto are available in both solo and orchestral tuning arrangements.

A variant and much less-commonly used form of solo tuning used in some Eastern European countries is (A-D-G-C), which uses three of the strings from orchestral tuning (A-D-G) and then adds a high "C" string. Some bassists with five string basses use a high "C" string as the fifth string, instead of a low "B" string. Adding the high "C" string facilitates the performance of solo repertoire with a high tessitura (range).

When using more than four strings, the player generally must choose between adding a higher or lower-tuned string, as construction of a six-stringed instrument is generally regarded as impractical. With the additional string, fingerboards must be made wider, and the tops must be made thicker in order to deal with the extra tension and stress from the additional string. Some five-stringed instruments are converted from ones originally constructed to utilize fewer strings, where the fingerboards have not been widened (often making for awkwardness and difficulties in fingering and bowing). Generally, however, there is no way around having a thicker top when an additional string is present.

Playing and performance considerations

Double bassists have the option to either stand or sit while playing the instrument. When standing, the double bass' height is set (by adjusting the endpin) so that the player may easily place the right hand close to the bridge, either with the bow (arco) or plucking (pizzicato). While personal opinions vary, often the endpin is set by aligning the first finger in either first or half position with the player's eye level. While sitting, a stool (which is measured by the player's seam length) is used. Traditionally, standing has been preferred by soloists although many now choose to play sitting down. Proponents of playing while sitting on a stool argue that it is easier to perform high-register passages.

When playing in the instrument's upper range (above the G below middle C), the player shifts his hand out from behind the neck and flattens it out, using the side of the thumb to press down the string. This technique is called thumb position and is also a technique used on the cello. While playing in thumb position, the fourth (little) finger is not used, as it is too short to produce a reliable tone.

Despite the size of the instrument, it does not project a loud volume, because its range is so low. When the bass is being used as an ensemble instrument in orchestra, usually between four and eight bassists will play the part in unison. When writing solo passages for the bass in orchestral or chamber music, composers typically ensure that the orchestration is light so it will not obscure the soloist's sound. In many non-orchestral settings, amplification via a specialized amplifier and loudspeakers is employed. In bluegrass and jazz, less amplification is used than in blues, psychobilly, or jam band-music. In the latter, the high overall volume due to other amplifiers and instruments may lead to acoustic feedback, a problem that is accentuated by the bass's large surface area and interior volume.

Performing on the bass can be physically demanding because the strings of the instrument are larger and thicker than those of smaller stringed instruments. Also, the spacing between notes on the fingerboard is larger due to the bass's size. This means that bass players have to shift positions more frequently. The increased use of playing techniques such as thumb position and modifications to the bass, such as the use of lighter-gauge strings at lower tension, have eased the difficulty of playing the instrument. Bass parts have relatively fewer fast passages, double stops, or large jumps in range.

As with all unfretted string instruments, performers must learn to precisely place their fingers to produce the correct pitch. Again, due to the instrument's size, more frequent hand movement is required, increasing the likelihood of intonation errors. For bassists with smaller hands, the large spaces between pitches may present a significant challenge, especially in the lowest range, where the spaces between notes are largest.

Until the 1990s, child-sized double basses were not widely available, and the large size of the bass meant that children were not able to start playing the instrument until their hand size and height would allow them to play a 3/4-size model (the most commonly available size). Starting in the 1990s, smaller half, quarter, eighth and even sixteenth-sized instruments became more widely available, which meant that children could start at a younger age.

The double bass's large size, combined with its relative fragility, causes some difficulty in safely transporting the instrument. As hard cases are both expensive and heavy, many bassists use soft cases, often referred to as "gig bags," to protect the instrument. Some players use wheeled carts or endpin-attached wheels to assist in transporting the instrument.

Classical repertoire

Solo works for double bass

1700s

The double bass as a solo instrument enjoyed a period of popularity during the 18th century and many of the most popular composers from that era wrote pieces for the double bass. The double bass, then often referred to as the Violone used different tunings from region to region. The "Viennese tuning" (A-D-F♯-A) was popular, and in some cases a fifth string or even sixth string was added. The popularity of the instrument is documented in Leopold Mozart's second edition of his Violinschulë, where he writes "One can bring forth difficult passages easier with the five-string violone, and I heard unusually beautiful performances of concertos, trios, solos, etc."

The earliest known concerto to exist for the double bass was written by Joseph Haydn ca.1763, which was presumably lost in the fire at the Eisenstadt library. The earliest concertos that exist today are by Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf, who composed two concertos for the double bass and a Sinfonia Concertante for viola and double bass. Other composers that have written concertos from this period include Johann Baptist Vanhal, Franz Anton Hoffmeister (3 concertos), Leopold Kozeluch, Anton Zimmermann, Antonio Capuzzi, Wenzel Pichl (2 concertos), and Johannes Matthias Sperger (18 concertos). While many of these names were leading figures to the music public of their time, they are generally unknown by contemporary audiences. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's concert aria, "Per Questa Bella Mano", K.612 for bass, double bass obbligato, and orchestra contains impressive writing for solo double bass of that period. It remains popular among both singers and double bassists today.

The double bass eventually evolved to fit the needs of orchestras that required lower notes and a louder sound. The leading double bassists from the mid- to late 18th century, such as Josef Kämpfer, Friedrich Pischelberger, and Johannes Mathias Sperger employed the "Viennese" tuning. Bassist Johann Hindle (1792-1862), who composed a concerto for the double bass, pioneered tuning the bass in fourths, which marked a turning point for the double bass and its role in solo works. Bassist Domenico Dragonetti was a prominent musical figure and an acquaintance of Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven. His playing was known all the way from his native Italy to the Tsar of Russia and he found a prominent place performing in concerts with the Philharmonic Society of London.

Beethoven's friendship with Dragonetti may have inspired Beethoven to write difficult, separate parts for the double bass in his symphonies which do not double the cello and the impressive passages in the third movement of the Fifth Symphony and last movement of the Ninth Symphony. Dragonetti wrote ten concertos for the double bass and many solo works for bass and piano. During Rossini's stay in London in the summer of 1824, he composed his Duetto for cello and double bass for Dragonetti and the cellist David Salomons. Dragonetti frequently played on a three string double bass tuned G-D-A from top to bottom. The use of only the top three strings was popular for bass soloists and Principal bassists in orchestras in the 19th century, because it reduced the pressure on the wooden top of the bass, which was thought to create a more resonant sound. As well, the low "E" strings used during the 19th century were thick cords made of gut, which were difficult to tune and play.

1800s

In the 19th century, the opera conductor, composer, and bassist Giovanni Bottesini was considered the "Paganini of the double bass" of his time. His compositions were written in the popular Italian opera style of the 19th century, which exploit the double bass in a way that was not seen beforehand. They require virtuosic runs and great leaps to the highest registers of the instrument, even into the realm of harmonics. These compositions were considered to be unplayable by many bassists in the early part of the 20th century, but now are frequently performed. During the same time, a prominent school of bass players in the Czech region arose, which included Franz Simandl, Theodore Albin Findeisen, Josef Hrabe, Ludwig Manoly, and Adolf Mišek . Simandl and Hrabe were also pedagogues whose method books and studies continue to be used in the modern day.

1900s-present

The leading figure of the double bass in the early 20th century was Serge Koussevitzky, best known as conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, who popularized the double bass in modern times as a solo instrument. Because of improvements to the double bass with steel strings and better set-ups, the bass is now played at a more advanced level than ever before and more and more composers have written works for the double bass. In the mid-century and in the following decades, many new concerti were written for the double bass, including Nikolaos Skalkottas's Concerto (1942), Eduard Tubin's Concerto (1948), Lars-Erik Larsson's Concertino (1957), Charles Wuorinen's Concert for Double Bass Alone (1961), Gunther Schuller's Concerto (1962), and Hans Werner Henze's Concerto (1966).

In the 1970s and 1980s, new concerti included Nino Rota's Divertimento for Double Bass and Orchestra (1973), Jean Françaix's Concerto (1975), Einojuhani Rautavaara's Angel Of Dusk (1980), Gian Carlo Menotti's Concerto (1983), Christopher Rouse's Concerto (1985), and Henry Brant's Ghost Nets (1988). In the 2000s, new concerti include Kalevi Aho's Concerto (2005), John Harbison's Concerto for Bass Viol (2006), and André Previn's Double Concerto for violin, double bass, and orchestra (2007). Krzysztof Penderecki and Wolfgang Rihm are currently writing concertos for the double bass .

Reinhold Glière wrote and Intermezzo and Tarantella for double bass and piano, Op. 9, No. 1 and No. 2 and a Praeludium and Scherzo for double bass and piano, Op. 32 No.1 and No.2. Paul Hindemith wrote a rhythmically-challenging Double Bass Sonata in 1949. Giacinto Scelsi wrote two double bass pieces called Nuits in 1972, and then in 1976, he wrote Maknongan, a piece for any low-voiced instrument, such as double bass, contrabassoon, or tuba. Vincent Persichetti wrote solo works for many instruments which he calle "Parables"; he wrote Parable XVII for Double Bass, Op. 131 in 1974. Sofia Gubaidulina penned a Sonata for double bass and piano in 1975. Fernando Grillo wrote the "Suite No.1" for double bass (1983/2005). Queen's John Deacon played a double bass for Brian May's song '39. Jacob Druckman wrote a piece for solo double bass entitled Valentine. US double bass soloist and composer Bertram Turetzky (born 1933) has performed and recorded more than 300 pieces written by and for him. He writes chamber music, baroque music, classical, jazz, renaissance music, improvisational music and world music

US minimalist composer Philip Glass wrote a prelude focused on the lower register which was scored for timpani and double bass. Italian composer Sylvano Bussotti, whose composing career spans from the 1930s to the 2000s, wrote a solo work for bass in 1983 entitled Naked Angel Face per contrabbasso. Fellow Italian composer Franco Donatoni wrote a piece called Lem for contrabbasso in the same year. In 1989, French composer Pascal Dusapin (born 1955) wrote a solo piece called In et Out for double bass. In 1996, the Sorbonne-trained Lebanese composer Karim Haddad composed Ce qui dort dans l'ombre sacrée ("He who sleeps in the sacred shadows") for Radio France's Presence Festival. Renaud Garcia-Fons (born 1962) is a French double-bass player and composer, notable for drawing on jazz, folk, and Asian music for recordings of his pieces like Oriental Bass (1997). In 2005, Mario Davidovsky wrote an electro-acoustic work called Synchronisms No. 11 for contrabass and magnetic tape.

Chamber music with double bass

A well-known chamber work that includes the double bass is Mozart's Serenade for strings in G major, "Eine kleine Nachtmusik" K.525, which is scored for two violins, viola, cello, and double bass. The work is more often performed today with more than one player to a part, such as by a chamber string orchestra. Mozart also included the double bass in addition to 12 wind instruments for his "Gran Partita" Serenade, K.361 (370a). One of Beethoven's most famous pieces during his lifetime was his Septet in E flat major, Op.20 for violin, viola, clarinet, horn, bassoon, cello, and double bass. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the common group to play at dance functions was two violins and a double bass. Beethoven also composed Six Minuets, WoO9 and Six Ländlers, WoO15 for this instrumentation.

Gioacchino Rossini composed six string sonatas for two violins, cello, and double bass at age twelve over the course of three days in 1804 which remain his most famous instrumental works. Luigi Boccherini, whose father was a double bass player, composed three string quintets for two violins, viola, cello, and double bass. Antonín Dvořák also used the string quartet with double bass for his String Quintet in G major, Op.77 as did Darius Milhaud for his second quintet for strings, Op.316. Franz Schubert's Trout Quintet is scored for piano, violin, viola, cello, and double bass. The piece is thought to have been influenced by Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Quintet for piano and strings, Op. 87 which uses the same instruments. The instrumentation was used again in the 20th century by Ralph Vaughan Williams for his Piano Quintet. Felix Mendelssohn wrote a Sextet for piano and strings, Op.110 using piano, violin, two violas, cello, and double bass.

During the 20th century, the double bass was used in a variety of chamber works including Erwin Schulhoff's Concertino for flute/piccolo, viola, and double bass; Paul Hindemith's Octet for clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, two violas, cello, and double bass; and Serge Prokofiev's Quintet, Op.39 for oboe, clarinet, violin, cello, and double bass. The double bass continues to be used in chamber music by more contemporary composers. Examples of such pieces include Fred Lerdahl's Waltzes for violin, viola, cello, and double bass; Mario Davidovsky's Festino for guitar, viola, cello, and double bass; and Iannis Xenakis's Morsima-Amorsima for piano, violin, cello, and double bass.

Orchestral passages and solos

The double bass in the baroque and classical periods would typically double the cello part in orchestral passages. A notable exception would be Haydn, who composed solo passages for the double bass in his Symphonies No.6 “Le Matin”, No.7 “Le midi”, No.8 “Le Soir”, No. 31 “Horn Signal, and No. 45 “Farewell”, but who otherwise would group the bass and cello parts together. Beethoven paved the way for separate double bass parts which would become more common in the romantic era. The scherzo and trio from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is a famous orchestral excerpt as is the recitative at the beginning of the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

While orchestral bass solos are somewhat rare, there are some notable examples. Johannes Brahms, whose father was a double bass player, wrote many difficult and prominent parts for the double bass in his symphonies. Richard Strauss assigned the double bass daring parts, and his symphonic poems and operas stretch the instrument to its limits. "The Elephant" from Camille Saint-Saëns' The Carnival of the Animals is a satirical portrait of the double bass. The third movement of Gustav Mahler's first symphony features a solo for the double bass which quotes the children's song "Frere Jacques", transposed into a minor key. Sergei Prokofiev's "Lieutenant Kijé Suite" features a difficult and very high double bass solo in the "Romance" movement. Benjamin Britten's The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra contains a prominent passage for the double bass section.

Double bass ensembles

Ensembles made up entirely of double basses, though relatively rare, also exist, and several composers have written or arranged for such ensembles. Gunther Schuller and Jacob Druckman both composed quartets for four basses. Larger ensemble works include Galina Ustvolskaya's Composition No. 2, “Dies Irae” (1973), for eight double basses, piano, and wooden cube, Jose Serebrier's George and Muriel (1986), for solo bass, double bass ensemble, and chorus, and Gerhard Samuel's What of my music! (1979), for soprano, percussion, and 30 double basses.

Active double bass ensembles include L'Orchestre de Contrebasses (6 members),[10] Bass Instinct (6 members),[11] Bassiona Amorosa (6 members),[12] the Chicago Bass Ensemble (4+ members),[13] The Bass Gang (4 members),[14] and the ensembles of Ball State University (12 members) and the Hartt School of Music. The Amarillo Bass Base of Amarillo, Texas once featured 52 double bassists,[15][16], and The London Double Bass Sound, who have released a CD on Cala Records, have 10 players.[17]

In addition, the double bass sections of some orchestras perform as an ensemble, such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's Wacker Consort.[18] There is an increasing number of published compositions and arrangements for double bass ensembles, and the International Society of Bassists regularly features double bass ensembles (both smaller ensembles as well as very large "mass bass" ensembles) at its conferences, and sponsors the biennial David Walter Composition Competition, which includes a division for double bass ensemble works.

Use in jazz

See also List of jazz bassists (which includes both double bass and electric bass guitar players)

Beginning around 1890, the early New Orleans jazz ensemble (which played a mixture of marches, ragtime, and dixieland music) was initially a marching band with sousaphone (or occasionally bass saxophone) supplying the bass line. As the music moved into bars and brothels, the double bass gradually replaced these wind instruments. Many early bassists doubled on both the "brass bass" and "string bass," as the instruments were then often referred to. Bassists played "walking" basslines, scale-based lines which outlined the harmony.

Because an unamplified double bass is generally the quietest instrument in a jazz band, many players of the 1920s and 1930s used the slap style, slapping and pulling the strings so that they make a rhythmic "slap" sound against the fingerboard. The slap style cuts through the sound of a band better than simply plucking the strings, and allowed the bass to be more easily heard on early sound recordings, as the recording equipment of that time did not favor low frequencies.[19] For more about the slap style, see "Modern playing styles," below.

Double bass players have contributed to the evolution of jazz. Examples include swing era players such as Jimmy Blanton, who played with Duke Ellington, and Oscar Pettiford, who pioneered the instrument's use in bebop. The "cool" style of jazz was influenced by players such as Scott LaFaro and Percy Heath, whose solos were melodic. Paul Chambers (who worked with Miles Davis on the famous Kind of Blue album) achieved renown for being one of the first jazz bassists to play bebop solos in arco (bowed) style.

Free jazz was influenced by the composer/bassist Charles Mingus (who also contributed to hard bop) and Charlie Haden, best known for his work with Ornette Coleman. Beginning in the 1970s, some jazz bandleaders such as saxophonist Sonny Rollins and fusion bassist Jaco Pastorius began to substitute the electric bass guitar for the double bass. Apart from the jazz styles of jazz fusion and Latin-influenced jazz, the double bass is still widely used in jazz. The sound and tone of the plucked double bass is distinct from that of the fretted bass guitar. The bass guitar produces a different sound than the double bass, because its strings are usually stopped with the aid of metal frets. As well, bass guitars usually have a solid wood body, which means that the sound is produced by electronic amplification of the vibration of the strings.

Use in bluegrass

The string bass is the most commonly-used bass instrument in bluegrass music and is almost always plucked, though some modern bluegrass bassists have also used a bow. The bluegrass bassist is part of the rhythm section, and is responsible for keeping a steady beat, whether fast, slow, in 4/4 time, 2/4 or 3/4 time. The Englehardt and Kay brands of laminate basses have long been popular choices for bluegrass bassists. Most bluegrass bassists use the 3/4 size bass, but the full-size and 5/8 size basses are also used.

Early pre-bluegrass traditional music was often accompanied by the cello; Natalie Haas points out that in the US, you can find "... old photographs, and even old recordings, of American string bands with cello." However, "the cello dropped out of sight in folk music and became associated with the orchestra". [20]The cello did not reappear in bluegrass until the 1990s and 2000s. Some contemporary bluegrass bands favor the electric bass, because it is easier to transport on tour that the large and delicate upright bass. However, the bass guitar has a different musical quality than the plucked upright bass. The slower attack and the percussive, woody tone of the upright bass gives it a more "earthy" or "natural" sound than an electric bass, particularly when gut strings are used.

Common rhythms in bluegrass bass playing involve (with some exceptions) plucking on beats 1 and 3 in 4/4 time; beats 1 and 2 in 2/4 time, and on the downbeat in 3/4 time (waltz time). Bluegrass bass lines are usually simple, typically staying on the root and fifth of each chord throughout most of a song. There are two main exceptions to this "rule". Bluegrass bassists often do a diatonic "walkup" or "walkdown" in which they play every beat of a bar for one or two bars, typically when there is a chord change. In addition, if a bass player is given a solo, they may play a walking bass line with a note on every beat or play a pentatonic scale-influenced bassline.

An early bluegrass bassist to rise to prominence was Howard Watts (also known as Cedric Rainwater), who played with Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys beginning in 1944.[21] One of the most famous classical bassists, Edgar Meyer, has frequently branched out into newgrass, Old Time, Jazz, and other genres.

Slap-style bass

Slap-style bass is sometimes used in bluegrass bass playing. When bluegrass bass players snap the string by pulling it until it hits the fingerboard or hit the strings against the fingerboard, it adds the high-pitched percussive "clack" or "slap" sound to the low-pitched bass notes, sounding much like the clacks of a tap dancer. Slapping is a subject of minor controversy in the bluegrass scene. Even slapping experts such as Mike Bub say, "...don't slap on every gig" or in songs where it is "not appropriate." As well, bluegrass bassists who play slap-style on live shows often slap less on records. Bub and his mentor Jerry McCoury rarely do slap bass on recordings. While bassists such as Jack Cook slap bass "...on the occasional faster Clinch Mountain boys song", bassists such as "...Gene Libbea, Missy Raines, Jenny Keel, or Barry Bales [rarely] slap bass."[22]

Bluegrass bassist Mark Schatz, who teaches slap bass in his Intermediate Bluegrass Bass DVD acknowledges that slap bass "...has not been stylistically very predominant in the music I have recorded." He notes that "Even in traditional bluegrass slap bass only appears sporadically and most of what I've done has been on the more contemporary side of that (Tony Rice, Tim O'Brien)." Schatz states that he would be "... more likely to use it [slap] in a live situation that on a recording - for a solo or to punctuate a particular place in a song or tune where I wouldn't be obliterating someone's solo.".[23] Another bluegrass method, Learn to Play Bluegrass Bass, by Earl Gately, also teaches bluegrass slap bass technique.

Use in popular music

In 1952, the upright bass was a standard instrument in rock and roll music, Marshall Lytle of Bill Haley & His Comets being but one example. In the 1940s, a new style of dance music called rhythm and blues developed, incorporating elements of the earlier styles of blues and swing. Louis Jordan, the first innovator of this style, featured a double bass in his group, the Tympany Five.[24] The double bass remained an integral part of pop lineups throughout the 1950s, as the new genre of rock and roll was built largely upon the model of rhythm and blues, with strong elements also derived from jazz, country, and bluegrass. However, double bass players using their instruments in these contexts faced inherent problems. They were forced to compete with louder horn instruments (and later amplified electric guitars), making bass parts difficult to hear. The double bass is difficult to amplify in loud concert venue settings, because it can be prone to feedback "howls". The double bass is large and awkward to transport, which also created transportation problems for touring bands.

In 1951, Leo Fender independently released his Precision Bass, the first commercially successful electric bass guitar.[25] The electric bass was easily amplified with its built-in pickups, easily portable (less than a foot longer than an electric guitar), and easier to play in tune, thanks to the metal frets. In the 1960s and 1970s bands were playing at louder volumes and performing in larger venues. The electric bass was able to provide the huge, highly-amplified stadium-filling bass tone that the pop and rock music of this era demanded, and the double bass receded from the limelight of the popular music scene.

The upright bass began making a modest comeback in popular music in the mid-1980s, in part due to a renewed interest in earlier forms of rock and country music. In the 1990s, improvements in pickups and amplifier designs for electro-acoustic horizontal and upright basses made it easier for bassists to get a good, clear amplified tone from an acoustic instrument. Some popular bands decided to anchor their sound with an upright bass instead of an electric bass. A trend for "unplugged" performances further helped to enhance the public's interest in the upright bass and acoustic bass guitars.

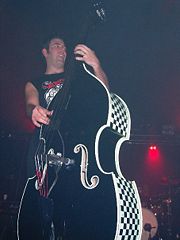

The double bass is also favored over the electric bass guitar in many rockabilly and psychobilly bands. In such bands the bassist often plays with great showmanship, using slapping technique, sometimes spinning the bass around or even physically climbing onto the instrument while performing; this style was pioneered c. 1953 by Marshall Lytle, the bassist for Bill Haley & His Comets,[26] and modern performers of such stunts include Lee Rocker of the Stray Cats, Scott Owen from The Living End and Jimbo from Reverend Horton Heat. Primus's Les Claypool used an upright bass for the song "Mr. Krinkle," from Pork Soda, and for the song "Over the Falls," from the Brown Album. Jeff Ament of Pearl Jam uses a double bass in the song "Nothing as It Seems," on the album Binaural. Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers uses a double bass for the song "Cabron," on the 2002 album By the Way. Rapper & producer Dr. Dre used a double bass during the beginning of the track Deep Cover, featuring Snoop Doggy Dogg. The same double bass was used later again for the Big Pun song "Twinz (Deep COver '98)" featuring Fat Joe off Big Pun's album, Capital Punishment. Shannon Burchell, of the australian folk-rock group The John Butler Trio, makes extensive use of double basses, performing extended live solo's in songs such as Betterman.

Modern playing styles

In popular music genres, the instrument is usually played with amplification and almost exclusively played with the fingers, pizzicato style. The pizzicato style varies between different players and genres. Some players perform with the sides of one, two, or three fingers, especially for walking basslines and slow tempo ballads, because this is purported to create a stronger and more solid tone. Some players use the more nimble tips of the fingers to play fast-moving solo passages or to pluck lightly for quiet tunes.The use of amplification allows the player to have more control over the tone of the instrument, because amplifiers have equalization controls which allow the bassist to accentuate certain frequencies (often the bass frequencies) while de-accentuating some frequencies (often the high frequencies, so that there is less finger noise).

An unamplified acoustic bass' tone is limited by the frequency responsiveness of the instrument's hollow body, which means that the very low pitches may not be as loud as the higher pitches. With an amplifier and equalization devices, a bass player can boost the low frequencies, which evens out the frequency response. As well, the use of an amplifier can increase the sustain of the instrument, which is particularly useful for accompaniment during ballads and for melodic solos with held notes.

In traditional jazz, swing, polka, rockabilly, and psychobilly music, it is sometimes played in the slap style. This is a vigorous version of pizzicato where the strings are "slapped" against the fingerboard between the main notes of the bass line, producing a snare drum-like percussive sound. The main notes are either played normally or by pulling the string away from the fingerboard and releasing it so that it bounces off the fingerboard, producing a distinctive percussive attack in addition to the expected pitch. Notable slap style bass players, whose use of the technique was often highly syncopated and virtuosic, sometimes interpolated two, three, four, or more slaps in between notes of the bass line.

"Slap style" may have influenced electric bass guitar players who from about 1970 developed a technique called "slap and pop," where the thumb of the plucking hand is used to hit the string, making a slapping sound but still allowing the note to ring, and the index or middle finger of the plucking hand is used to pull the string back so it hits the fretboard, achieving the pop sound described above.

Double bassists

Historical

- Domenico Dragonetti (1763-1846) Virtuoso, composer, conductor

- Giovanni Bottesini (1821-1889) Virtuoso, composer, conductor

- Franz Simandl (1840-1912) Virtuoso, composer

- Edouard Nanny (1872-1943) Virtuoso, composer

- Serge Koussevitzky (1874-1951) Conductor, virtuoso, composer

Contemporary (1900s-present)

Classical

Some of the most influential contemporary classical double bass players are known as much for their contributions to pedagogy than for their performing skills, such as US bassist Oscar G. Zimmerman (1910-1987), known for his teaching at the Eastman School of Music and, for 44 summers at the Interlochen National Music Camp in Michigan and French bassist François Rabbath (b. 1931) who developed a new bass method which divided the entire fingerboard into six positions. Bassists noted for their virtuoso solo skills include US player Gary Karr (b. 1941) and Finnish bassist-composer Teppo Hauta-Aho (born 1941). The Italien double bassist and composer Fernando Grillo. For a longer list, see the List of contemporary classical double bass players.

Jazz

Notable jazz bassists from the 1940s to the 1950s included bassist Jimmy Blanton (1918–1942) whose short tenure in the Duke Ellington Swing band (cut short by his death from tuberculosis) introduced new melodic and harmonic solo ideas for the instrument; bassist Ray Brown (1926–2002), known for backing Beboppers Dizzy Gillespie, Art Tatum and Charlie Parker, and forming the Modern Jazz Quartet; hard bop bassist Ron Carter (born 1937), who has appeared on 3,500 albums make him one of the most-recorded bassists in jazz history, including LPs by Thelonious Monk and Wes Montgomery and many Blue Note Records artists; and Paul Chambers (1935–1969), a member of the Miles Davis Quintet (including the landmark cool jazz recording Kind of Blue) and many other 1950s and 1960s rhythm sections, was known for his virtuosic improvisations.

In the experimental post 1960s eras, which saw the development of free jazz and jazz-rock fusion, some of the influential bassists included Charles Mingus (1922–1979), who was also a composer and bandleader whose music fused hard bop with black gospel music, free jazz and classical music; free jazz and post-bop bassist Charlie Haden (born 1937) is best known for his long association with saxophonist Ornette Coleman and for his role in the 1970s-era Liberation Music Orchestra, an experimental group; and fusion virtuoso Stanley Clarke (born 1951) is notable for his dexterity on both the double bass and the electric bass. In the 1990s and 2000s, one of the new "young lions" was Christian McBride (born 1972), who has performed with a range of veterans ranging from McCoy Tyner to fusion gurus Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, and who has released albums such as 2003's Vertical Vision. For a longer list, see the List of jazz bassists, which includes both double bass and electric bass players.

Other popular genres

Edgar Meyer (born 1960) is a notable bluegrass and newgrass player who has recorded for Sony. Well-known rockabilly bassists include Marshall Lytle (with Bill Haley & His Comets) and Lee Rocker (with 1980s-era rockabilly revivalists the Stray Cats). More recent rockabilly revivalists and psychobilly performers include Scott Owen (from the Australian rock band The Living End), "Jimbo" (from the US band Reverend Horton Heat), and Geoff Kresge (Tiger Army, ex-AFI).

See also

- Electric upright bass

- List of jazz bassists

- List of classical bassists

- Octobass

- Piccolo bass

- Bass guitar

- International Society of Bassists

- Bazantar

References

- ↑ The Orchestra: A User's Manual, Andrew Hugill with the Philharmonia Orchestra

- ↑ Chamber Music in the Vienna Double Bass Archive, Alfred Planyavsky

- ↑ The Double Bass, Jacob Head

- ↑ Planyavsky 1998

- ↑ A New History of the Double Bass, Paul Brun

- ↑ Gainesville Violins

- ↑ TheBassShop claims that gut strings recreate the tone used in bluegrass, rockabilly, Paul Chambers-era jazz, and baroque music. Available at: http://www.thebassshop.com/bass_accessories.html

- ↑ Jeff Sarli

- ↑ Bill Bentgen - 5 String Basses

- ↑ Official website of L'Orchestre de Contrebasses

- ↑ LOVEFiLM.com: Bass Instinct - Live In Vienna by none on DVD

- ↑ www.bassiona-amorosa.de

- ↑ Chicago Bass Ensemble - Home

- ↑ The Bass Gang, The Bass Gang, The Bass Gang, The Bass Gang, The Bass Gang,The Bass Gang

- ↑ http://home.mchsi.com/~donovan.stokes/volumeone.html

- ↑ http://www.bassgirls.com/bass_wyrickinez.htm

- ↑ Amazon.com: The London Double Bass Sound: Gary Karr, Ernest Bloch, Paul Desmond, Edward "Duke" Ellington, Jerome Kern, John & Paul McCartney Lennon, Niccolo Paganini, Cole Por...

- ↑ Wacker Consort and Northwestern Music Faculty to Perform, NewsCenter, Northwestern University

- ↑ Historic Jazz Fotos

- ↑ Looming Large: What's a cello got to do with a famous fiddler's tale? By Natalie Haas. Available at: http://www.allthingsstrings.com/article/default.aspx?articleid=21495

- ↑ Howard "Cedric Rainwater" Watts, Stewart Evans

- ↑ iBluegrass.com Article: The Low End February-02-2001 ©2001 iBluegrass.com. All rights reserved. By Kip Martin http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:opbTh79jK-8J:www.ibluegrass.com/vi_posting3.CFM%3Fp__i%3D1004%26p__r%3D%26p__a%3Dbass+bluegrass+%22slap+bass%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=2

- ↑ http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:0bSxq7Zh3tYJ:www.rockabillybass.com/markschatz.htm+bluegrass+%22slap+bass%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1

- ↑ Dallas Bartley - Small town Boy: Playing in the bands, Special Collections and Archives Department, Missouri State University

- ↑ The Electric Guitar: How We Got From Andrés Segovia To Kurt Cobain, Monica M. Smith

- ↑ Marshall Lytle: Granddaddy of the Doghouse, Rod Glaze

External links

- Bass at the Open Directory Project

- http://www.jazzdoublebass.com - Site featuring notable jazz Double Bass players and educational resources

- http://www.bluegrassbassplace.com - Site featuring Double Bass instruction as it relates to Bluegrass, New Grass & Rock-A-Billy

Kontrabaso]]