Ciconiiformes

| Storks | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oriental Stork, Ciconia boyciana

|

||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Genera | ||||||||||||||||

|

Anastomus |

Traditionally, the order Ciconiiformes has included a variety of large, long-legged wading birds with large bills: storks, herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, and several others. However recent DNA evidence might suggest that every member, except storks, are more related the Pelecaniformes, and thus belong to that group.[1] Ciconiiformes are known from the Late Eocene.

They occur in most of the warmer regions of the world and tend to live in drier habitats than the very similar herons, spoonbills, and ibises; they also lack the powder down that those groups use to clean off fish slime. Storks have no syrinx and are mute, giving no bird call; bill-clattering is an important mode of stork communication at the nest. Many species are migratory. Most storks eat frogs, fish, insects, earthworms, and small birds or mammals. There are 19 living species of storks in six genera.

Storks tend to use soaring, gliding flight, which conserves energy. Soaring requires thermal air currents. Ottomar Anschütz's famous 1884 album of photographs of storks inspired the design of Otto Lilienthal's experimental gliders of the late 19th century. Storks are heavy, with wide wingspans: the Marabou Stork, with a wingspan of 3.2 m (10.5 ft), joins the Andean Condor in having the widest wingspan of all living land birds.

Their nests are often very large and may be used for many years. Some have been known to grow to over 2 m (6 ft) in diameter and about 3 m (10 ft) in depth. Storks were once thought to be monogamous, but this is only partially true. They may change mates after migrations, and may migrate without a mate. They tend to be attached to nests as much as partners.

Storks' size, serial monogamy, and faithfulness to an established nesting site contribute to their prominence in mythology and culture.

Contents |

Taxonomic issues with Ciconiiformes

Following the development of research techniques in molecular biology in the late 20th century, in particular methods for studying DNA-DNA hybridisation, a great deal of new information has surfaced, much of it suggesting that many birds, although looking very different from one another, are in fact more closely related than was previously thought. Accordingly, the radical and influential Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy greatly enlarged the Ciconiiformes, adding many more families, including most of those usually regarded as belonging to the Sphenisciformes (penguins), Gaviiformes (divers), Podicipediformes (grebes), Procellariiformes (tubenosed seabirds), Charadriiformes, (waders, gulls, terns and auks), Pelecaniformes (pelicans, cormorants, gannets and allies), and the Falconiformes (diurnal birds of prey). The flamingo family, Phoenicopteridae, is related, and is sometimes classed as part of the Ciconiiformes.

However, morphological evidence suggests that the traditional Ciconiiformes should be split between two lineages, rather than expanded, although some non-traditional Ciconiiformes may be included in these two lineages.

The exact taxonomic placement of New World Vultures remains unclear.[2] Though both are similar in appearance and have similar ecological roles, the New World and Old World Vultures evolved from different ancestors in different parts of the world and are not closely related. Just how different the two families are is currently under debate, with some earlier authorities suggesting that the New World vultures belong in Ciconiiformes.[3] More recent authorities maintain their overall position in the order Falconiformes along with the Old World Vultures[4] or place them in their own order, Cathartiformes.[5] The South American Classification Committee has removed the New World Vultures from Ciconiiformes and instead placed them in Incertae sedis, but notes that a move to Falconiformes or Cathartiformes is possible.[2]

Some official bodies have adopted the proposed Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy almost entirely, however a more common approach worldwide has been to retain the traditional groupings, and modify rather than replace them in the light of new evidence as it comes to hand. The family listing here follows this more conservative practice. Bird taxonomy has been in a state of flux for some years, and it is reasonable to expect that the large differences between different classification schemes will continue to gradually resolve themselves as more evidence becomes available.

However, recently a DNA study found that the families Ardeidae, Balaenicipitidae, Scopidae and the Threskiornithidae belong to the Pelecaniformes. This would make Ciconiidae the only group.

Distinct and possibly widespread by the Oligocene, like most families of aquatic birds storks seem to have arisen in the Paleogene, maybe 40-50 million years ago (mya). For the fossil record of living genera, documented since the Middle Miocene (about 15 mya) at least in some cases, see the genus articles.

Though some storks are highly threatened, no species or subspecies are known to have gone extinct in historic times. A Ciconia bone found in a rock shelter on Réunion was probably of a bird taken there as food by early settlers; no known account mentions the presence of storks on the Mascarenes.

Living storks

Order Ciconiiformes

- Family Ciconiidae

- Genus Mycteria

- Milky Stork, Mycteria cinerea

- Yellow-billed Stork, Mycteria ibis

- Painted Stork, Mycteria leucocephala

- Wood Stork, Mycteria americana

- Genus Anastomus

- Asian Openbill Stork, Anastomus oscitans

- African Openbill Stork, Anastomus lamelligerus

- Genus Ciconia

- Abdim's Stork, Ciconia abdimii

- Woolly-necked Stork, Ciconia episcopus

- Storm's Stork, Ciconia stormi

- Maguari Stork, Ciconia maguari

- Oriental Stork, Ciconia boyciana (formerly in C. ciconia)

- White Stork, Ciconia ciconia

- Black Stork, Ciconia nigra

- Genus Ephippiorhynchus

- Black-necked Stork, Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus

- Saddle-billed Stork, Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis

- Genus Jabiru

- Jabiru, Jabiru mycteria

- Genus Leptoptilos

- Lesser Adjutant, Leptoptilos javanicus

- Greater Adjutant, Leptoptilos dubius

- Marabou Stork, Leptoptilos crumeniferus

- Genus Mycteria

Fossil storks

- Genus Palaeoephippiorhynchus (fossil: Early Oligocene of Fayyum, Egypt)

- Genus Grallavis (fossil: Early Miocene of Saint-Gérand-le-Puy, France, and Djebel Zelten, Libya) - may be same as Prociconia

- Ciconiidae gen. et sp. indet. (Ituzaingó Late Miocene of Paraná, Argentina)[6]

- Ciconiidae gen. et sp. indet. (Puerto Madryn Late Miocene of Punta Buenos Aires, Argentina)[7]

- Genus Prociconia (fossil: Late Pleistocene of Brazil) - may belong to modern genus Jabiru or Ciconia

- Genus Pelargosteon (fossil: Early Pleistocene of Romania)

- Ciconiidae gen. et sp. indet. - formerly Aquilavus/Cygnus bilinicus (fossil: Early Miocene of Břešťany, Czechia)

- cf. Leptoptilos gen. et sp. indet. - formerly L. siwalicensis (fossil: Late Miocene? - Late Pliocene of Siwalik, India)[8]

- Ciconiidae gen. et sp. indet. (fossil: Late Pleistocene of San Josecito Cavern, Mexico)[9]

The fossil genera Eociconia (middle Eocene of China) and Ciconiopsis (Deseado Early Oligocene of Patagonia, Argentina) are often tentatively placed with this family. A "ciconiiform" fossil fragment from the Touro Passo Formation found at Arroio Touro Passo (Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) might be of the living Wood Stork M. americana; it is at most of Late Pleistocene age, a few 10.000s of years<r

Etymology

The modern English word can be traced back to Proto-Germanic *sturkaz. Nearly every Germanic language has a descendant of this proto-language word to indicate the (White) stork. Related names also occur in many Eastern European, especially Slavonic languages, originating as Germanic loanwords.

According to the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, the Germanic root is probably related to the modern English "stark", in reference to the stiff or rigid posture of a European species, the White Stork. A non-Germanic word linked to it may be Greek torgos ("vulture").

In some West Germanic languages cognate words of a different etymology exist. They originate from *uda-faro, uda being related to water meaning something like swamp or moist area and faro being related to fare, so *uda-faro being he who walks in the swamp. In later times this name got reanalyzed as *ōdaboro, ōda "fortune, wealth" + boro "bearer" meaning he who brings wealth adding to the myth of storks as maintainers of welfare and bringing the children:

In Estonian, "stork" is toonekurg, which is derived from toonela (underworld in Estonian folklore) + kurg (crane). It may seem not to make sense to associate the now-common white stork with death, but at the times they were named, the now-rare black stork was probably the more common species. ef>Schmaltz Hsou (2007)</ref>.

Symbolism of storks

Childbirth

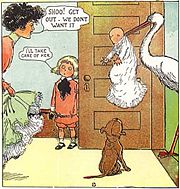

In Western culture the White Stork is a symbol of childbirth. In Victorian times the details of human reproduction were difficult to approach, especially in reply to a younger child's query of "Where did I come from?"; "The stork brought you to us" was the tactic used to avoid discussion of sex. This habit was derived from the once popular superstition that storks were the harbingers of happiness and prosperity, and possibly from the habit of some storks of nesting atop chimneys, down which the new baby could be imagined as entering the house.

The image of a stork bearing an infant wrapped in a sling held in its beak is common in popular culture. The small pink or reddish patches often found on a newborn child's eyelids, between the eyes, on the upper lip, and on the nape of the neck are sometimes still called "stork bites". In fact they are clusters of developing veins that often soon fade.

The stork's folkloric role as a bringer of babies and harbinger of luck and prosperity may originate from the Netherlands and Northern Germany, where it is common in children's nursery stories.

The Bible references the stork e.g. in Leviticus 11:19.

In popular culture

In Walt Disney's 4th classic Dumbo, the stork (more generally "Mr. Stork") delivers babies to their animal mothers. At the beginning of the film, he delivers Dumbo to Mrs. Jumbo. He is voiced by Sterling Holloway.

Several Warner Bros. cartoons — including Stork Naked and Apes of Wrath — cast a stork as a perpetually drunken employee of a baby-delivery service. Always losing his cargo en route to the intended recipients, the stork would find a replacement (always the wrong species) and deliver it to his clients. The stork was a bit player in these shorts, appearing at only the beginning and the end (where he returns to correct his mistake); the rest of the cartoons played out the interaction between the parents and the mismatched "child" they attempted to raise.[10]

Vlasic uses this child-bearing stork as a mascot in North America for its brand of pickles, merging the stork-baby mythology with the notion that pregnant women have an above-average appetite for pickles.

Regional symbolism

The white stork is the symbol of The Hague in the Netherlands, where about 25 percent of European storks breed, as well as of Poland, where the majority of the remainder breed. It is also a symbol of the region of Alsace in eastern France. It is also the national bird of Belarus. In Vietnam, the stork symbolize the strenuousness of poor Vietnamese farmers and the diligence of Vietnamese women.

Mythology of storks

If not otherwise indicated, these usually refer to the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia).

- The motto "Birds of a feather flock together" is appended to Aesop's fable of the farmer and the stork his net caught among the cranes that were robbing his fields of grain. The stork vainly pleaded to be spared, being no crane.

- The Hebrew word for stork - "Hasida" (חסידה) was equivalent to "devotee" (namely a devout, God-fearing, religiously observant or righteous, pious and kind woman); it is in fact the female form of the word "Hasid" (חסיד) which became identitied with the Hassidic movement of Judaism. And the care of storks for their young, in their highly visible nests, made the stork a widespread emblem of parental care. It was widely noted in ancient natural history that a stork pair will be consumed with the nest in a fire, rather than fly and abandon it.

- In Greek mythology, Gerana was an Æthiope, the enemy of Hera, who changed her into a stork, a punishment Hera also inflicted on Antigone, daughter of Laomedon of Troy (Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.93). Stork-Gerana tried to abduct her child, Mopsus. This accounted, for the Greeks, for the mythic theme of the war between the pygmies and the storks. In popular Western culture, there is a common image of a stork bearing an infant wrapped in cloths held in its beak; the stork, rather than absconding with the child Mopsus, is pictured as delivering the infant, an image of childbirth.

- An ancient etymology about the Pelasgians, ancient pre-Hellenic inhabitnats of Greece, links pelasgos to pelargos "stork", and postulates that the Pelasgians were migrants like storks, possibly from Egypt, where they nest.[11] Aristophanes deals effectively with this etymology in his comedy the Birds. One of the laws of "the storks" in the satirical cloud-cuckoo-land (punning on the Athenian belief that they were originally Pelasgians) is that grown-up storks must support their parents by migrating elsewhere and conducting warfare.[12]

- The stork is alleged in folklore to be monogamous although in fact this monogamy is serial monogamy, the pair bond lasting one season (see above). For Early Christians the stork became an emblem of a highly respected white marriage, that is, a chaste marriage. This symbolism endured to the seventeenth century, as in Henry Peacham's emblem book Minerva Britanna (1612) (see link).

- In Norse mythology, Hoenir gives to mankind the spirit gift, the óðr that includes will and memory and makes us human (see Rydberg link). Hoenir's epithets langifótr "long-leg" and aurkonungr "mire-king" identify him possibly as a kind of stork. Such a Stork King figures in northern European myths and fables. However, it is possible that there is confusion here between the White Stork and the more northerly-breeding Common Crane, which superficially resembles a stork but is completely unrelated.

- In rural Denmark, it means bad luck if a stork builds a nest on your roof; it means, that someone in the house will die before the end of the year.

- Though "Stork" is rare as an English surname, the Czech surname "Čapek" means "little stork".

- In Bulgarian folklore, the stork is a symbol of the coming spring (as this is the time when the birds return to nest in Bulgaria after their winter migration) and in certain regions of Bulgaria it plays a central role in the custom of Martenitsa: when the first stork is sighted it is time to take off the red-and-white Martenitsa tokens, for spring is truly come.

- For the Chinese, the stork was able to snatch up a worthy man, like the flute-player Lan Ts'ai Ho, and carry him to a blissful life.

- In Ancient Egypt the Saddle-billed Stork was associated with the human ba; they had the same phonetic value. The ba was the unique individual character of each human being: a stork with a human head was an image of the ba-soul, which unerringly migrates home each night, like the stork, to be reunited with the body during the Afterlife. [1]

- A series of sightings of a mysterious pterodactyl-like creature in South Texas' Rio Grande Valley in the 1970s has been attributed to an errant jabiru that become lost during a migratory flight and wound up in an unfamiliar region, or an Ephippiorhynchus stork escaped from captivity (see Big Bird).

Footnotes

- ↑ A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History. Shannon J. Hackett, et al. Science 320, 1763 (2008).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Remsen, J. V., Jr.; C. D. Cadena; A. Jaramillo; M. Nores; J. F. Pacheco; M. B. Robbins; T. S. Schulenberg; F. G. Stiles; D. F. Stotz & K. J. Zimmer. 2007. A classification of the bird species of South America. South American Classification Committee. Retrieved on 2007-10-15

- ↑ Sibley, Charles G. and Burt L. Monroe. 1990. Distribution and Taxonomy of the Birds of the World. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04969-2. Accessed 2007-04-11.

- ↑ Sibley, Charles G., and Jon E. Ahlquist. 1991. Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: A Study in Molecular Evolution. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04085-7. Accessed 2007-04-11.

- ↑ Ericson, Per G. P.; Anderson, Cajsa L.; Britton, Tom; Elżanowski, Andrzej; Johansson, Ulf S.; Kallersjö, Mari; Ohlson, Jan I.; Parsons, Thomas J.; Zuccon, Dario & Mayr, Gerald (2006): Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils. Biology Letters online: 1-5. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523 PDF preprint Electronic Supplementary Material (PDF)

- ↑ Tarsometatarsus fragments somewhat similar to Mycteria: Cione et al. (2000), Noriega & Cladera (2005)

- ↑ Specimen MEF 1363: Incomplete skeleton of a large stork somewhat similar to Jabiru but apparently more plesiomorphic: Noriega & Cladera (2005)

- ↑ Specimens BMNH 39741 (holotype, left proximal tarsometatarsus) and BMNH 39734 (right distal tibiotarsus). Similar to Ephippiorhynchus and Leptotilos, may be from a small female of Leptotilos falconeri, from L. dubius, or from another species: Louchart et al. (2005)

- ↑ Distal radius of a mid-sized Ciconia or smallish Mycteria: Steadman et al. (1994)

- ↑ Friedwald & Beck (1981)

- ↑ Strabo refers to this in Geography Book V, Section II, Part 4.

- ↑ Line 1355 and following.

References

- Cione, Alberto Luis; de las Mercedes Azpelicueta, María; Bond, Mariano; Carlini, Alfredo A.; Casciotta, Jorge R.; Cozzuol, Mario Alberto; de la Fuente, Marcelo; Gasparini, Zulma; Goin, Francisco J.; Noriega, Jorge; Scillatoyané, Gustavo J.; Soibelzon, Leopoldo; Tonni, Eduardo Pedro; Verzi, Diego & Guiomar Vucetich, María (2000): Miocene vertebrates from Entre Ríos province, eastern Argentina. [English with Spanish abstract] In: Aceñolaza, F.G. & Herbst, R. (eds.): El Neógeno de Argentina. INSUGEO Serie Correlación Geológica 14: 191-237. PDF fulltext

- Friedwald, Will & Beck, Jerry (1981): The Warner Brothers Cartoons. Scarecrow Press Inc., Metuchen, N.J.. ISBN 0-8108-1396-3

- Louchart, Antoine; Vignaud, Patrick; Likius, Andossa; Brunet, Michel & and White, Tim D. (2005): A large extinct marabou stork in African Pliocene hominid sites, and a review of the fossil species of Leptoptilos. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 50(3): 549–563. PDF fulltext

- Noriega, Jorge Ignacio & Cladera, Gerardo (2005): First Record of Leptoptilini (Ciconiiformes: Ciconiidae) in the Neogene of South America. Abstracts of Sixth International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution: 47. PDF fulltext

- Schmaltz Hsou, Annie (2007): O estado atual do registro fóssil de répteis e aves no Pleistoceno do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil ["The current state of the fossil record of Pleistocene reptiles and birds of Rio Grande do Sul"]. Talk held on 2007-JUN-20 at Quaternário do RS: integrando conhecimento, Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. PDF abstract

- Steadman, David W.; Arroyo-Cabrales, Joaquin; Johnson, Eileen & Guzman, A. Fabiola (1994): New Information on the Late Pleistocene Birds from San Josecito Cave, Nuevo Leon, Mexico. Condor 96(3): 577-589. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

External links

- 24 h Camera Live 24h camera from Stork's nest in Poland

- Scott MacDonald, "The Stork" emblematic uses

- Storks Image documentation

- Stork family Live webcam image from Hungary. Please allow a few seconds to download.

- Stork videos on the Internet Bird Collection

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||