Stockport

| Stockport | |

|

|

|

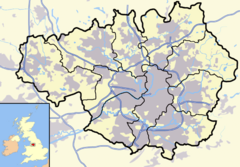

Stockport shown within Greater Manchester |

|

| Population | 136,082 (2001 Census) |

|---|---|

| - Density | 11,937 per mi² (4,613 per km²) |

| OS grid reference | |

| - London | 157 mi (253 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | Stockport |

| Metropolitan county | Greater Manchester |

| Region | North West |

| Constituent country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | STOCKPORT |

| Postcode district | SK1-SK3, SK5-SK8 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| European Parliament | North West England |

| UK Parliament | Stockport |

| List of places: UK • England • Greater Manchester | |

Stockport (pronunciation) is a large town in Greater Manchester, England. It lies on elevated ground on the River Mersey at the influx of the rivers Goyt and Tame, 6.1 miles (9.8 km) southeast of the city of Manchester. Stockport is the largest settlement of the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport, and has a population of 136,082, the wider borough being 281,000.

Stockport in the 16th century was known for the cultivation of hemp and rope manufacture and in the 18th century the town had one of the first mechanised silk factories in the United Kingdom. However, Stockport's predominant industries of the 19th century were the cotton and allied industries. Stockport was also at the centre of the country's hatting industry which by 1884 was exporting more than six million hats a year. In December 1997 the last Stockport hat works closed. The town's hatting heritage is preserved at 'Hat Works - the Museum of Hatting'.

Dominating the western approaches to the town is the Stockport Viaduct. Built in 1840, the viaduct's 27 brick arches over the River Mersey carry the mainline railways from Manchester to Birmingham and London. This structure featured as the background in many paintings by L.S. Lowry.

Contents |

History

Toponymy

Stockport was first recorded as "Stokeport" in 1170.[1][2] The currently accepted etymology is Old English stoc, a market place, with port, a hamlet (but more accurately a minor settlement within an estate); hence, a market place at a hamlet.[1][2]

Older derivations include stock or stoke, a stockaded place or castle, with port, a wood, hence a castle in a wood.[3] The castle part of the name probably refers to Stockport Castle, a 12th century motte-and-bailey first mentioned in 1173.[4] Other derivations have been formed, based on early variants of the name such as Stopford and Stockford. There is evidence that a ford across the Mersey existed at the foot of the town centre street now known as Bridge Street Brow. Stopford retains a use in the adjectival form, Stopfordian, used for Stockport-related items, and pupils at Stockport Grammar School style themselves as Stopfordians.[5] By contrast, former pupils of nearby Stockport School are known as Old Stoconians, perhaps from the Old English name for the town.

Stockport has never been a sea or river port. The Mersey is not navigable to anything much above canoe size, and in the centre of Stockport has been culverted and the main shopping street, Merseyway, is built above it.

Early history

The earliest evidence for human occupation in the wider area are microliths from the hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic period (the Middle Stone Age, about 8000–3500 BC) and weapons and tools from the Neolithic period (the New Stone age, 3500–2000 BC). Early Bronze Age (2000–1200 BC) remains include stone hammers, flint knives, palstaves (ie bronze) and funery urns; all finds have been chance discoveries, rather than a systematic search of a known site. There is a gap in the age of finds between about 1200 BC and the Roman period (ie after about 70 AD). This may indicate depopulation, possibly due to a poorer climate.[6]

There is little evidence of a Roman military station at Stockport, despite a strong local tradition.[7][8] It is assumed that roads from Cheadle to Ardotalia (Melandra) and Manchester to Buxton crossed close to the town centre. The preferred site is at a ford over the Mersey, known to be paved in the eighteenth century, but it has never been shown that this or any of the roads in the area are Roman. Hegginbotham reported (in 1892) the discovery of Roman mosaics at Castle Hill (the area around Stockport market) in the late eighteenth century, during the construction of a mill, but noted it was 'founded on tradition only'; substantial stonework found in the area has never been dated by modern methods. However, Roman coins and pottery were probably found there during the eighteenth century. A cache of coins dating 375–8 may have come from the banks of the Mersey at Daw Bank; these were possibly buried for safekeeping at the side of a road.[7]

Six coins from the reigns of the Anglo-Saxon English Kings Edmund (reigned 939–946) and Eadred (reigned 946–955) were found during ploughing at Reddish Green in 1789.[1][9] There is contrasting source material about the significance of this; Arrowsmith takes this as evidence for existence of a settlement at that time, but Morris states the find could be "an isolated incident". This small cache is the only Anglo-Saxon find in the area.[1] However, the etymology Stoc-port suggests inhabitation.[8]

No part of Stockport appears in the Domesday Book of 1086. The area north of the Mersey was part of the hundred of Salford, which was poorly surveyed. The area south of the Mersey was part of the Hamestan (Macclesfield) hundred. (Cheadle, Bramhall, Bredbury, and Romiley are mentioned, but these all lay just outside the town limits.) The survey includes valuations of the Salford hundred as a whole and Cheadle (etc) for the times of Edward the Confessor (ie just before the Norman invasion of 1066) and the time of the survey. The reduction in value is taken as evidence of destruction by William the Conqueror's men in the campaigns generally known as the Harrying of the North. The omission of Stockport was once taken as evidence that destruction was so complete that a survey was not needeed (see eg Husain[10]). Arrowsmith argues from the etymology that Stockport may have still been a market place associated with a larger estate, and so would not be surveyed separately. The Anglo-Saxon landholders in the area were dispossessed and the land divided amongst the new Norman rulers. The first borough charter was granted in about 1220 and was the only basis for local government for six hundred years.

A castle held by Geoffrey de Costentin is recorded as a rebel stronghold against Henry II in 1172–3. There is an incorrect local tradition that Geoffrey was the king's son, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, who was one of the rebels.[11] Dent gives the size of the castle as about 30x60 m, and suggests it was similar in pattern to those at Pontefract and Launceston. The castle was probably ruinous by the middle of the sixteenth century, and in 1642 it was agreed to demolish it. Castle Hill, possibly the motte, was levelled in 1775 to make space for Warren's mill, see below.[8][12] Nearby walls, once thought to be either part of the castle or of the town walls, are now thought to be revetments to protect the cliff face from erosion.[13]

Industrialisation

Stockport was one of the prototype textile towns.[14] In the early eighteenth century, England was not capable of producing silk of sufficient quality to be used as the warp in woven fabrics. Suitable thread had to be imported from Italy, where it was spun on water-powered machinery. In about 1717 John Lombe travelled to Italy and copied the design of the machinery. On his return he obtained a patent on the design, and went into production in Derby. When Lombe tried to renew his patent in 1732, silk spinners from towns including Manchester,Macclesfield, Leek, and Stockport successfully petitioned parliament to not renew the patent. Lombe was paid off, and in 1732 Stockport's first silk mill (indeed, the first water-powered textile mill in the north-west of England) was opened on a bend in the Mersey. Further mills were opened on local brooks. Silk weaving expanded until in 1769 two thousand people were employed in the industry. By 1772 the boom had turned to bust, possibly due to cheaper foreign imports; by the late 1770s trade had recovered.[15] The cycle of boom and bust would continue throughout the textile era.

The combination of a good water power site (described by Rodgers as "by far the finest of any site within the lowland" [of the Manchester region][14]) and a workforce used to textile factory work meant Stockport was well-placed to take advantage of the phenomenal expansion in cotton processing in the late eighteenth century. Warren's mill in the market place was the first. Power came from an undershot water wheel in a deep pit, fed by a tunnel from the River Goyt. The positioning on high ground, unusual for a water powered mill, contributed to an early demise, but the concept of moving water around in tunnels proved successful, and several tunnels were driven under the town from the Goyt to power mills. [16] In 1796, James Harrisson drove a wide cut from the Tame which fed several mills in the Park, Portwood.[17] Other water-powered mills were built on the Mersey.

Hatmaking was established in north Cheshire and south-east Lanchashire by the 16th century. In the early 1800s the number of hatters in the area began to increase, and a reputation for quality work was created. The London firm of Miller Christy bought out a local firm in 1826, a move described by Arrowsmith as 'a watershed'. By the latter part of the century hatting had changed from a manual to a mechanised process, and was one of Stockport's primary employers; the area, with nearby Denton, was the leading national centre. Support industries, such as blockmaking, trimmings, and leatherware, became established. The First World War cut off overseas markets, which established local industries and eroded Stockports eminence. Even so, in 1932 over 3000 people worked in the industry, making it the third biggest employer, after textiles and engineering. The depression of the 1930s and changes in fashion greatly reduced the demand for hats, and the demand that existed was met by cheaper wool products made elsewhere, for example the Luton area. By 1966–7 all the major companies merged to form Associated British Hat Manufacturers, leaving Christy's and Wilson's (at Denton) as the last two factories in production. First Wilson's, and then (in 1997) Christy's closed, bringing to an end over 400 years of hatting in the area.[18] The industry is commemorated the UK's only dedicated hatting museum, Hat Works.[19]

The town was connected to the national canal network by the 5 miles of the Stockport branch of the Ashton Canal opened in 1797 which continued in use until the 1930s. Much of it is now filled in, but there is an active campaign to re-open it for leisure uses.

From the 17th century Stockport became a centre for the hatting industry and later the silk industry. Stockport expanded rapidly during the Industrial Revolution, helped particularly by the growth of the cotton manufacturing industries. However, economic growth took its toll, and 19th century philosopher Friedrich Engels wrote in 1844 that Stockport was "renowned as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes in the whole of the industrial area".[20]

Recent history

Since the start of the 20th century Stockport has moved away from being a town dependent on cotton and its allied industries to one with a varied base. It makes the most of its varied heritage attractions, including a national museum of hatting, a unique system of underground Second World War air raid tunnel shelters in the town centre, and a late medieval merchants' house on the 700-year-old Market Place.

In 1967 the Stockport air disaster occurred, when a British Midland Airways C-4 Argonaut aeroplane crashed in the Hopes Carr area of the town, resulting in the deaths of 72 passengers.

In recent years, Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council has embarked on an ambitious regeneration scheme, known as Future Stockport. The plan is to bring over 3,000 residents into the centre of the town, and revitalise its residential property and retail markets, in a similar fashion to the nearby city of Manchester. Many ex-industrial areas around the town's core will be brought back into productive use as mixed-use residential and commercial developments.

Governance

Most of the town is within the historic county boundaries of Cheshire (south of the Mersey), although Reddish and the Four Heatons lay within the historic boundaries of Lancashire (north of the Mersey).

Civic history

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 made Stockport a municipal borough divided into six wards with a council consisting of 14 Aldermen and 42 Councillors. In 1888, its status was raised to County Borough, becoming the County Borough of Stockport. Since 1972, Stockport has been twinned with in Béziers in France.[21] In 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972 Stockport amalgamated with neighbouring districts to form the Unitary Authority of the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport in the now ceremonial metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.

Parliamentary representation

There are four parliamentary constituencies in the Stockport Metropolitan Borough: Stockport, Cheadle, Hazel Grove, and Denton and Reddish.

Stockport has been represented by Labour MP Ann Coffey since 1992.

Mark Hunter has been the Liberal Democrat MP for Cheadle since a 2005 by-election.

Andrew Stunell has been the Liberal Democrat MP for Hazel Grove since 1997.

The constituency of Denton and Reddish bridges Stockport and Tameside; the current member is Andrew Gwynne.

Geography

- Further information: Geography of Greater Manchester

| for Stockport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

70

6

1

|

50

7

1

|

60

9

3

|

50

12

4

|

60

15

7

|

70

18

10

|

70

20

12

|

80

20

12

|

70

17

10

|

80

14

8

|

80

9

4

|

80

7

2

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| temperatures in °C precipitation totals in mm source: "Records and averages". Yahoo! Weather (2008). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Imperial conversion

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At (53.408°, -2.149°), and 157 miles (253 km) northwest of London, Stockport stands on elevated ground, 6.1 miles (9.8 km) southeast of Manchester City Centre, at the confluence of the rivers Goyt and Tame. It shares a common boundary with the City of Manchester.

Divisions and suburbs

|

|||||

Demography

- Further information: Demography of Greater Manchester

| Stockport Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Stockport[22] | Stockport MB[23] | England |

| Total population | 136,082 | 284,528 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 95.5% | 95.7% | 91% |

| Asian | 2.0% | 2.1% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.5% | 0.4% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 74.9% | 75.4% | 72% |

| Muslim | 1.8% | 1.8% | 3.1% |

| No religion | 15.3% | 14.2% | 15% |

As of the 2001 UK census, Stockport had a population of 136,082. The 2001 population density was 11,937 per mi² (4,613 per km²), with a 100 to 94.0 female-to-male ratio.[24] Of those over 16 years old, 32%.0 were single (never married) and 50.2% married.[25] Stockport's 58,687 households included 33.1% one-person, 33.7% married couples living together, 9.7% were co-habiting couples, and 10.4% single parents with their children, these figures were similar to those of Stockport Metropolitan Borough and England.[26] Of those aged 16–74, 29.2% had no academic qualifications, significantly higher than that of 25.7% in all of Stockport Metropolitan Borough but significantly similar to 28.9% in all of England.[27][23]

Although suburbs such as Woodford, Greater Manchester, Bramhall and Hazel Grove rank amongst the wealthiest areas of the United Kingdom and 45% of the borough is green space, districts such as Edgeley,Adswood and Brinnington suffer from widespread poverty and post-industrial decay. In the north-west of the borough are the relatively prosperous areas of Heaton Moor and Heaton Mersey, which together with Heaton Chapel and Heaton Norris comprise the so-called Four Heatons.

Opinions on the general quality of life in Stockport greatly differ. In its favour, some highlight its proximity to Manchester, and its abundance of amenities; but its perceived grittiness and loutish youth culture earned it 12th place in the internet-based 2004 guide Crap Towns: The 50 Worst Places To Live In The UK (however, given that its fellows on this list were places such as Oxford, Winchester, Liverpool (European Capital of Culture 2008), and tiny London commuter belt villages, the relevance of the list is disputed).

Economy

Stockport's principal commercial district is located in the town centre, with branches of most high-street stores to be found in the Merseyway Shopping Centre or The Peel Centre. Grand Central Leisure boasts an Olympic sized swimming pool, a ten-screen cinema, bars, a bowling alley, health complex, and several restaurants. Stockport is located seven miles (10 km) from Manchester city centre, making it convenient for commuters and shoppers.

In 2008 the council's £500M plans to redevelop the town centre were cancelled. The construction company, Lend Lease Corporation, pulled out of the project, blaming the credit crunch for their choice.[28]

Culture

Landmarks and attractions

Stockport is home to the following:

- Stockport boasts the UK's only hat museum, the "Hat Works" based in Wellington Mill - a thriving hat factory in Victorian times.[29]

- Stockport Viaduct is one of the western Europe's biggest brick structures,[30] the 111 feet (34 m) high, four-track railway viaduct over the River Mersey on the line to Manchester which represents a major feat of Victorian engineering, built in 21 months at a cost of £70,000. Eleven million bricks were used in its construction, opening in 1842. The foundation stone was laid on March 10, 1839.

- Staircase House is a Grade II* listed medieval townhouse in the Market Place. The building has been modified several times, but is probably the oldest secular building in Stockport.[31]

- Stockport Story Museum, detailing over 10,000 years of Stockport's history. This museum has free admission and is housed within Staircase House.

- Stockport Town Hall, with its ballroom, described by Poet Laureate, John Betjeman as 'magnificent' containing the largest Wurlitzer theatre organ in Britain designed by Sir Alfred Brumwell Thomas.

- Stockport College with sites in the town centre and Heaton Moor

- Underbank Hall in the centre of Stockport is a late 16th century timber framed building, built as the townhouse of the Arderne family from nearby Bredbury. It remained in the family until 1823, and since 1824 has been used as a bank. The current main banking hall lies behind the 16th century part and dates from 1915.[31] The building is listed Grade II*.

- Stockport Air Raid Shelters is a museum based around the underground tunnels dug during World War II to protect local inhabitants during air raids

- Vernon Park. This is the main municipal park, located a short distance to the east towards Bredbury. It was opened on September 20th, 1858 on the anniversary of the Battle of Alma in the Crimean War. Named after Lord Vernon who presented the land for the park to the town.

- St. Elisabeth's church, Reddish, and model village. Mill community designed in the main by Alfred Waterhouse for the workers from Houldsworth Mill, at the time the largest cotton mill in the world.

- St Mary's Church on the Market Place is the town's oldest place of worship with parts dating to the early 14th century and houses the Stockport Heritage centre run by local volunteers on market days.

Sports

Stockport is home to two professional sports teams, both of which play at Edgeley Park stadium:

Stockport County F.C. play in Football League One;. Their claim to fame is that they currently hold the record for the most consecutive Football League wins without conceding a goal with nine, achieved in 2007.

Sale Sharks Rugby Union club, won the Guinness Premiership title in 2006 and boast current England internationals Mark Cueto, Charlie Hodgson and Andrew Sheridan; Scotland's Jason White as well as capped overseas stars including Sébastien Chabal, Sébastien Bruno.

Stockport Metro Swimming Club, based at Grand Central Pools is the most successful British swimming club, through the last three Olympic Games. Stockport Metro swimmers have claimed 50% of British swimming's medal haul. In the 1996 Atlanta games Graeme Smith won bronze in the 1500 m freestyle [32], in the 2004 Athens games Stephen Parry won bronze in the 200 m butterfly [33], and in the 2008 Beijing games Keri-Anne Payne and Cassie Patten won silver and bronze, respectively, in the 10km marathon swim. [34]

Stockport has three athletics clubs - Manchester Harriers & AC, Stockport Harriers & AC, and DASH Athletics Club. Manchester Harriers train at William Scholes' Playing Fields in Gatley, and they organise highly-regarded schools cross country races throughout the winter. Stockport Harriers are based at Woodbank Park in Offerton, and have several International middle-distance and endurance athletes including Steve Vernon. DASH Athletics Club are the newest Club in Stockport based at both Hazel Grove Recreation Centre,and the Regional Athletics Arena at Sportcity in Manchester. In 2006 DASH AC Coach Geoff Barratt was UK Athletics' Development Coach of the Year, and in 2007 the club won England Athletics North West Junior Club and North West Overall Club of The Year accolades.

It is also the birthplace of Fred Perry, the late tennis player. Perry is the last Briton to win both the Men's Singles titles in Wimbledon and the US Open (both in 1936), making him the last British male to win a Grand Slam title.

Transport

The Manchester orbital M60 motorway and A6 road to London cross at Stockport. Stockport railway station is a mainline station on the Manchester spur of the West Coast Main Line. Manchester Airport (Ringway), the busiest in the UK outside London, is located five miles (8 km) southwest of the town.

Notable people

As one of the larger towns in the UK, Stockport and its surrounding villages have had many notable residents throughout their history including dashing weatherman Chris Fawkes, actor Dominic Monaghan, best-known for his role in the movie adaptations of The Lord of the Rings (who attended Aquinas College in Stockport), John Amaechi, NBA Star and activist, novelist Christopher Isherwood, engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth, tennis player Fred Perry, TV presenter David Dickinson, judge John Bradshaw and architect Norman Foster. Distinguished first-class cricketers Fred Ridgway and Maurice Tremlett were born in Stockport and played test cricket for England.[35][36] Also, drummer Dominic Howard from the successful band Muse hails from Stockport.

See also

- Stockport Air Disaster

- St Mary's Church, Stockport

- St Peter's Church, Stockport

- St George's Church, Heaviley

- Stockport Peel Centre

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Arrowsmith (1997) p. 23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mills, A D (1997). Dictionary of English Place-Names (2nd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280074-4.

- ↑ "Local History". Stockport MBC web pages. Retrieved on 2007-04-02.

- ↑ "Stockport Castle". Pastscape.org.uk. Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- ↑ "Old Stopfordians' Association". Stockport Grammar School - an independent school near Manchester, England. Retrieved on 2007-04-03.

- ↑ Arrowsmith (1997) pp. 9–14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Arrowsmith (1997) pp. 18–19.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Dent (1977).

- ↑ Morris, Mike, ed.. Medieval Manchester; A Regional Study. The Archaeology of Greater Manchester volume 1. Manchester: Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit. pp. pp 13–15. ISBN 0-946126-02-X. "… foolhardy to attempt any historical interpretation of the pre-tenth century evidence. (it) could represent an isolated incident.".

- ↑ Husain (1973) p. 12

- ↑ See Dent (1977) for the traditional view; and Arrowmith (1997), p. 31 for the refutation.

- ↑ Pevsner and Hubbard (1971), p 338.

- ↑ Arrowsmith (1996).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rodgers (1962) p. 13.

- ↑ Arrowsmith (1997) pp. 97–101.

- ↑ Dranfield, Coral (2006). Rivers under your feet: the story of Stockport's water tunnels. Kevin Dranfield. ISBN 0-9553995-0-5.

- ↑ Arrowsmith (1997), p. 130; Ashmore (1975).

- ↑ McKnight, Penny (2000). Stockport hatting. Stockport: Stockport M.B.C., Community Services Division. pp. pp 1–9. ISBN 0-905164-84-9.

• Arrowsmith (1997), pp. 156–7, 225–6. - ↑ "Hat Works - about us". Hat Works. Retrieved on 2008-10-02.

• Williamson, Hannah (2006). "The Character of Hat Works". Manchester Region History Review 17 (2): 111–121. - ↑ Engels, Frederick (1969). "The great Towns". The Condition of the Working Class in England. Panther. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/ch04.htm. "Stockport is renowned throughout the entire district as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes, and looks, indeed, especially when viewed from the viaduct, excessively repellent.".

- ↑ "Twin towns". Stockport.gov.uk. Retrieved on 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "KS06 Ethnic group: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (25 January 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Stockport Metropolitan Borough key statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved on 17 August 2008.

•"Stockport Metropolitan Borough ethnic group data". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved on 17 August 2008. - ↑ "KS01 Usual resident population: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (7 February 2005). Retrieved on 17 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS04 Marital status: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS20 Household composition: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

•"Stockport Metropolitan Borough household data". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved on 17 August 2008. - ↑ "KS13 Qualifications and students: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "Town centre future on scrap heap". Stockport Express (13 August 2008). Retrieved on 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Hat Works Web Site

- ↑ "Stockport Railway Viaduct".

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Arrowsmith, Peter (1996). Recording Stockport's Past: Recent Investigations of Historic Sites in the Borough of Stockport. Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 0-905164-20-2.

- ↑ "The Water Zone Profiles - Graeme Smith". Retrieved on 2008-09-26.

- ↑ "It's a swimming bronze for Stockport". Retrieved on 2008-09-26.

- ↑ "British duo take 10km swim medals". Retrieved on 2008-09-26.

- ↑ "Fred Ridgway player profile". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-27.

- ↑ Wisden Cricket Monthly. "Maurice Tremlett player profile". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-27.

Bibliography

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1996). Recording Stockport's Past: Recent Investigations of Historic Sites in the Borough of Stockport. Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 0-905164-20-2.

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1997). Stockport: a History. Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 0-905164-99-7.

- Dent, JS (1977). "Recent investigations on the site of Stockport Castle". Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society 79: 1–13.

- Glen, Robert (1984). Urban workers in the early Industrial Revolution. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-1103-3.

- Harris, Brian; Alan Thacker and C. P. Lewis (1979). A history of the county of Chester. The Victoria history of the counties of England. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 0-19-722749-X.

- Hartwell, Clare; Matthew Hyde and Nikolaus Pevsner (2004). Lancashire : Manchester and the South-East. The buildings of England. New Haven, Conn. ; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10583-5.

- Holden, Roger N. (1998). Stott & Sons : architects of the Lancashire cotton mill. Lancaster: Carnegie. ISBN 1-85936-047-5.

- Husain, B M C (1973). Cheshire under the Norman Earls. A history of Cheshire. 4. Chester: Cheshire Community Council Publications Trust.

- Jenkins, Simon (1999). England's thousand best churches. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-713-99281-6.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1969). Lancashire. The buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-140-71036-1.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Edward Hubbard (1971). Cheshire. The buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-140-71042-6.

- Rodgers, H B (1962). "The landscapes of eastern Lancastria". in Carter, Charles Frederick (ed). Manchester and its region : a survey prepared for the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held in Manchester August 29 to September 5 1962. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. pp. 1–16.

- Williams, Mike; D A Farnie (1992). Cotton mills in Greater Manchester. Preston: Carnegie. ISBN 0-948789-69-7.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||