Standard Model

| Standard model of particle physics | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Standard model | ||||||||

History of...

|

||||||||

The Standard Model of particle physics is a theory of three of the four known fundamental interactions and the elementary particles that take part in these interactions. These particles make up all visible matter in the universe.

The standard model is a gauge theory of the electroweak and strong interactions with the gauge group SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1). To date, all experimental tests of the three forces described by the Standard Model have agreed with its predictions.

The Standard Model falls short of being a complete theory of fundamental interactions because it does not include gravity and because it is incompatible with the recent observation of neutrino oscillations. In order to introduce neutrino masses, the standard model can be modified by adding a non-renormalizable interaction of lepton fields with the square of the Higgs field. This is natural in certain grand unified theories, and if new physics appears at about 1016 GeV, the neutrino masses are of the right order of magnitude.

Contents |

Historical background

The way in which the electromagnetic and weak interactions are mixed together in the Standard Model was discovered by Sheldon Glashow in 1963. Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam incorporated the Higgs mechanism in 1967, giving the theory its modern form.[1][2] The same Higgs mechanism gives masses to all the fundamental fermions (quarks and leptons) in the model.

After the discovery at CERN of neutral weak currents,[3][4][5][6] caused by Z boson exchange, the electroweak model became widely accepted. For their discoveries, Glashow, Salam, and Weinberg shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics. The W and Z bosons were produced experimentally in 1981, confirming their predicted masses.

The theory of the strong interaction evolved thanks to the efforts of many people, aquiring its modern form around 1973 and 1974, when it became clear that fractionally charged quarks were physical constituents of hadrons.

Overview

In physics, the dynamics of both matter and energy in nature is presently best understood in terms of the kinematics and interactions of fundamental particles. To date, science has managed to reduce the laws which seem to govern the behavior and interaction of all types of matter and energy we are aware of, to a small core of fundamental laws and theories. A major goal of physics is to find the 'common ground' that would unite all of these into one integrated model of everything, in which all the other laws we know of would be special cases, and from which the behavior of all matter and energy can be derived (at least in principle). "Details can be worked out if the situation is simple enough for us to make an approximation, which is almost never, but often we can understand more or less what is happening." (Feynman's lectures on Physics, Vol 1. 2–7)

The standard model is a grouping of two major theories — quantum electroweak and quantum chromodynamics — which provides an internally consistent theory describing interactions between all experimentally observed particles. Technically, quantum field theory provides the mathematical framework for the standard model. The standard model describes each type of particle in terms of a mathematical field. For a technical description of the fields and their interactions, see standard model (mathematical formulation).

Particle Content

Particles of matter

All fermions in the Standard Model are spin-½, and follow the Pauli Exclusion Principle in accordance with the spin-statistics theorem.

| Generation 1 | Generation 2 | Generation 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quarks | Up |

u | Charm |

c | Top |

t |

| Down |

d | Strange |

s | Bottom |

b | |

| Leptons | Electron Neutrino |

νe | Muon Neutrino |

νμ | Tau Neutrino |

ντ |

| Electron | e− | Muon | μ− | Tau |

τ− | |

Apart from their antiparticle partners, a total of twelve different fermions are known and accounted for. They are classified according to how they interact (or equivalently, what charges they carry): six of them are classified as quarks (up, down, charm, strange, top, bottom), and the other six as leptons (electron, muon, tau, and their corresponding neutrinos).

Pairs from each classification are grouped together to form a generation, with corresponding particles exhibiting similar physical behavior (see table of fermions).

The defining property of the quarks is that they carry color charge, and hence, interact via the strong force. The infrared confining behavior of the strong force results in the quarks being perpetually bound to one another forming color-neutral composite particles (hadrons) of either two quarks (mesons) or three quarks (baryons). The familiar proton and the neutron are examples of the two lightest baryons. Quarks also carry electric charges and weak isospin. Hence they interact with other fermions electromagnetically and via the weak nuclear interactions.

The remaining six fermions that do not carry color charge are defined to be the leptons. The three neutrinos do not carry electric charge either, so their motion is directly influenced only by means of the weak nuclear force. For this reason neutrinos are notoriously difficult to detect in laboratories. However, the electron, muon and the tau lepton carry an electric charge so they interact electromagnetically, too.

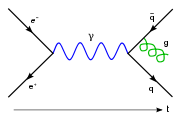

Force mediating particles

Forces in physics are the ways that particles interact and influence each other. At a macro level, the electromagnetic force allows particles to interact with one another via electric and magnetic fields, and the force of gravitation allows two particles with mass to attract one another in accordance with Newton's Law of Gravitation. The standard model explains such forces as resulting from matter particles exchanging other particles, known as force mediating particles. When a force mediating particle is exchanged, at a macro level the effect is equivalent to a force influencing both of them, and the particle is therefore said to have mediated (i.e., been the agent of) that force. Force mediating particles are believed to be the reason why the forces and interactions between particles observed in the laboratory and in the universe exist.

The known force mediating particles described by the Standard Model also all have spin (as do matter particles), but in their case, the value of the spin is 1, meaning that all force mediating particles are bosons. As a result, they do not follow the Pauli Exclusion Principle. The different types of force mediating particles are described below.

- Photons mediate the electromagnetic force between electrically charged particles. The photon is massless and is well-described by the theory of quantum electrodynamics.

- The W+, W−, and Z gauge bosons mediate the weak interactions between particles of different flavors (all quarks and leptons). They are massive, with the Z being more massive than the W±. The weak interactions involving the W± act on exclusively left-handed particles and right-handed antiparticles. Furthermore, the W± carry an electric charge of +1 and −1 and couple to the electromagnetic interactions. The electrically neutral Z boson interacts with both left-handed particles and antiparticles. These three gauge bosons along with the photons are grouped together which collectively mediate the electroweak interactions.

- The eight gluons mediate the strong interactions between color charged particles (the quarks). Gluons are massless. The eightfold multiplicity of gluons is labeled by a combination of color and an anticolor charge (e.g., red–antigreen).[7] Because the gluon has an effective color charge, they can interact among themselves. The gluons and their interactions are described by the theory of quantum chromodynamics.

The interactions between all the particles described by the Standard Model are summarized in the illustration immediately above and to the right.

| Electromagnetic Force | Weak Nuclear Force | Strong Nuclear Force | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photon | γ | W+, W−, and Z Gauge Bosons |

W+, W−, Z | Gluons | g |

The Higgs boson

The Higgs particle is a hypothetical massive scalar elementary particle predicted by the Standard Model, and the only fundamental particle predicted by that model which has not been directly observed as of yet. This is because it requires an exceptionally large amount of energy and beam luminosity to create and observe at high energy colliders. It has no intrinsic spin, and thus, (like the force mediating particles, which also have integral spin) is also classified as a boson.

The Higgs boson plays a unique role in the Standard Model, and a key role in explaining the origins of the mass of other elementary particles, in particular the difference between the massless photon and the very heavy W and Z bosons. Elementary particle masses, and the differences between electromagnetism (caused by the photon) and the weak force (caused by the W and Z bosons), are critical to many aspects of the structure of microscopic (and hence macroscopic) matter. In electroweak theory it generates the masses of the massive leptons (electron, muon and tau); and also of the quarks.

As yet, no experiment has directly detected the existence of the Higgs boson, but there is some indirect evidence for it. It is hoped that Large Hadron Collider experiments conducted at CERN will bring experimental evidence confirming the existence of the particle.

Science, a journal of original scientific research, has reported: "...experimenters may have already overlooked a Higgs particle, argues theorist Chien-Peng Yuan of Michigan State University in East Lansing and his colleagues. They considered the simplest possible supersymmetric theory. Ordinarily, theorists assume that the lightest of theory's five Higgses is the one that drags on the W and Z. Those interactions then feed back on Higgs and push its mass above 121 times the mass of the proton, the highest mass searched for at CERN's Large Electron–Positron (LEP) collider, which ran from 1989 to 2000. But it's possible that the lightest Higgs weighs as little as 65 times the mass of a proton and has been missed, Yuan and colleagues argue in a paper to be published in Physical Review Letters`."[8]

Field content

The standard model has the following fields:

Spin 1

- A U(1) gauge field Y with coupling y (weak hypercharge or weak U(1))

- An SU(2) gauge field W with coupling w (weak SU(2) or weak isospin )

- An SU(3) gauge field G with coupling g (gluons or strong color)

Spin 1/2

The spin 1/2 particles are in representations of the gauge groups. For the U(1), the representation is the value of the weak hypercharge.

The fermionic fields are:

- left-handed SU(3) singlet, SU(2) doublet with U(1) charge -1 (left-handed lepton)

- a right-handed SU(3) singlet, SU(2) singlet with U(1) charge 2 (right-handed lepton)

- A left-handed SU(3) triplet, SU(2) doublet, with U(1) charge 1 (left handed quarks)

- A right-handed SU(3) triplet, SU(2) singlet, with U(1) charge -4/3(right handed up-type quark)

- A right-handed SU(3) triplet, SU(2) singlet, U(1) charge 1/3 (right handed down-type quark)

This describes one generation of leptons and quarks, and there are three generations, so there are three copies of each field. Note that there are twice as many left-handed lepton field components as right handed components in each generation, but an equal number of left-handed and right-handed quark fields.

Spin 0

- An SU(2) doublet H with U(1) charge -1 (Higgs field)

note that  , summed over the two SU(2) components, is invariant under both SU(2) and under U(1), and so it can appear as a renormalizable term in the Lagrangian, as can its square.

, summed over the two SU(2) components, is invariant under both SU(2) and under U(1), and so it can appear as a renormalizable term in the Lagrangian, as can its square.

This field acquires a vacuum expectation value, leaving a combination of the weak isospin and hypercharge unbroken. This is the electromagnetic gauge group, and the photon remains massless. The standard formula for the electric charge (which defines the normalization of the weak hypercharge, which would otherwise be somewhat arbitrary) is:

Lagrangian

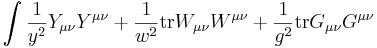

The Lagrangian for the spin 1 and spin 1/2 fields is the most general renormalizable gauge field Lagrangian with no fine tunings:

Spin 1:

where the traces are over the SU(2) and SU(3) indices hidden in W and G respectively. The two-index objects are the field strengths derived from W and G the vector fields. There are also two extra hidden parameters: the theta angles for SU(2) and SU(3).

Note that the spin 1/2 particles can have no mass terms, because there is no right/left helicity pair with the same SU(2) and SU(3) representation and the same weak hypercharge. This means that if the gauge charges were conserved in the vacuum, none of the spin 1/2 particles could ever swap helicity, and they would all be massless.

For a neutral fermion, for example, a hypothetical right-handed lepton N, or  in relatvistic two-spinor notation, with no SU(3),SU(2) representation and zero charge, it is possible to add the term:

in relatvistic two-spinor notation, with no SU(3),SU(2) representation and zero charge, it is possible to add the term:

and this term gives the neutral fermion a Majorana mass. Since the generic value for M will be of order 1, such a particle would generically be unacceptably heavy.

Note that the interactions are completely determined by the theory--- the leptons introduce no extra parameters.

Higgs Mechanism

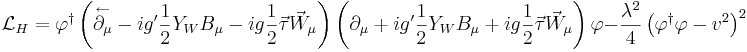

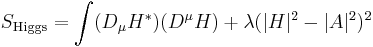

The Lagrangian for the Higgs includes the most general renormalizable self interaction:

The parameter A2 has dimensions of mass, and it gives the location where the classical Lagrangian is at a minimimum. In order for the Higgs mechanism to work, A^2 must be a positive number. A has units of mass, and it is the only parameter in the standard model which is not dimensionless. It is also much smaller than the Planck scale, it is approximately equal to the Higgs mass and sets the scale for the mass of everything else. This is the only real fine-tuning to a small nonzero value in the standard model, and it is called the Hierarchy problem.

It is traditional to choose the SU(2) gauge so that the Higgs doublet in the vacuum has expectation value (H_0,0).

Masses and CKM matrix

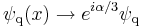

The rest of the interactions are the most general spin-0 spin 1/2 Yukawa interactions, and there are many of these. These consitute most of the free parameters in the model. The Yukawa couplings generate the masses and mixings once the Higgs gets its vacuum expectation value.

The terms L^*HR generate a mass term for each of the three generations of leptons. There are 9 of these terms, but by relabeling L and R, the matrix can be diagonalized. Since only the upper component of H is nonzero, the upper SU(2) component of L mixes with R to make the electron, the muon, and the tau, leaving over a lower massless component, the neutrino.

The terms QHU generate up masses, while QHD generate down masses. But since there is more than one right-handed singlet in each generation, it is not possible to diagonalized both with a good basis for the fields, and there is an extra CKM matrix.

Theoretical Aspects

Construction of the Standard Model Lagrangian

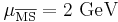

| Symbol | Description | Renormalization scheme (point) |

Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Electron mass | 511 keV | |

|

Muon mass | 106 MeV | |

|

Tau lepton mass | 1.78 GeV | |

|

Up quark mass | ( ) ) |

1.9 MeV |

|

Down quark mass | ( ) ) |

4.4 MeV |

|

Strange quark mass | ( ) ) |

87 MeV |

|

Charm quark mass | ( ) ) |

1.32 GeV |

|

Bottom quark mass | ( ) ) |

4.24 GeV |

|

Top quark mass | (on-shell scheme) | 172.7 GeV |

|

CKM 12-mixing angle | 0.229 | |

|

CKM 23-mixing angle | 0.042 | |

|

CKM 13-mixing angle | 0.004 | |

|

CKM CP-Violating Phase | 0.995 | |

|

U(1) gauge coupling | ( ) ) |

0.357 |

|

SU(2) gauge coupling | ( ) ) |

0.652 |

|

SU(3) gauge coupling | ( ) ) |

1.221 |

|

QCD Vacuum Angle | ~0 | |

|

Higgs quadratic coupling | Unknown | |

|

Higgs self-coupling strength | Unknown |

Technically, quantum field theory provides the mathematical framework for the standard model, in which a Lagrangian controls the dynamics and kinematics of the theory. Each kind of particle is described in terms of a dynamical field that pervades space-time. The construction of the standard model proceeds following the modern method of constructing most field theories: by first postulating a set of symmetries of the system, and then by writing down the most general renormalizable Lagrangian from its particle (field) content that observes these symmetries.

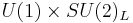

The global Poincaré symmetry is postulated for all relativistic quantum field theories. It consists of the familiar translational symmetry, rotational symmetry and the inertial reference frame invariance central to the theory of special relativity. The local SU(3) SU(2)

SU(2) U(1) gauge symmetry is an internal symmetry that essentially defines the standard model. Roughly, the three factors of the gauge symmetry give rise to the three fundamental interactions. The fields fall into different representations of the various symmetry groups of the Standard Model (see table). Upon writing the most general Lagrangian, one finds that the dynamics depend on 19 parameters, whose numerical values are established by experiment. The parameters are summarized in the table at right.

U(1) gauge symmetry is an internal symmetry that essentially defines the standard model. Roughly, the three factors of the gauge symmetry give rise to the three fundamental interactions. The fields fall into different representations of the various symmetry groups of the Standard Model (see table). Upon writing the most general Lagrangian, one finds that the dynamics depend on 19 parameters, whose numerical values are established by experiment. The parameters are summarized in the table at right.

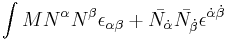

The QCD sector

The electroweak sector

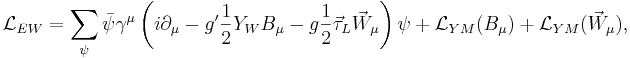

The electroweak sector is a Yang-Mills gauge theory with the symmetry group  ,

,

where  is the

is the  gauge field;

gauge field;  is the weak hypercharge — the generator of the U(1) group;

is the weak hypercharge — the generator of the U(1) group;  is the three-component SU(2) gauge field;

is the three-component SU(2) gauge field;  are the Pauli matrices — infinitesimal generators of the SU(2) group, the subscript

are the Pauli matrices — infinitesimal generators of the SU(2) group, the subscript  indicates that they only act on left fermions;

indicates that they only act on left fermions;  and

and  are coupling constants.

are coupling constants.

The Higgs sector

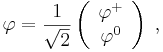

In the standard model the Higgs field is a complex spinor of the group  ,

,

where the indexes  and

and  indicate the

indicate the  -charges of the components; the

-charges of the components; the  -charge of both components is equal 1.

-charge of both components is equal 1.

Before the symmetry breaking the Higgs Lagrangian is given as

Additional Symmetries of the Standard Model

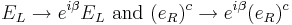

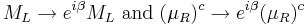

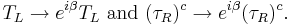

From the theoretical point of view, the standard model exhibits additional global symmetries that were not postulated at the outset of its construction. There are four such symmetries and are collectively called accidental symmetries, all of which are continuous U(1) global symmetries. The transformations leaving the Lagrangian invariant are

The first transformation rule is shorthand to mean that all quark fields for all generations must be rotated by an identical phase simultaneously. The fields  ,

,  and

and  ,

,  are the 2nd (muon) and 3rd (tau) generation analogs of

are the 2nd (muon) and 3rd (tau) generation analogs of  and

and  fields.

fields.

By Noether's theorem, each of these symmetries yields an associated conservation law. They are the conservation of baryon number, electron number, muon number, and tau number. Each quark carries 1/3 of a baryon number, while each antiquark carries -1/3 of a baryon number. The conservation law implies that the total number of quarks minus number of antiquarks stays constant throughout time. Within experimental limits, no violation of this conservation law has been found.

Similarly, each electron and its associated neutrino carries +1 electron number, while the antielectron and the associated antineutrino carry -1 electron number, the muons carry +1 muon number and the tau leptons carry +1 tau number. The standard model predicts that each of these three numbers should be conserved separately in a manner similar to the baryon number. These numbers are collectively known as lepton family numbers (LF). The difference in the symmetry structures between the quark and the lepton sectors is due to the masslessness of neutrinos in the standard model. However, it was recently found that neutrinos have small mass, and oscillate between flavors, signaling the violation of these three quantum numbers.

In addition to the accidental (but exact) symmetries described above, the standard model exhibits a set of approximate symmetries. These are the SU(2) Custodial Symmetry and the SU(2) or SU(3) quark flavor symmetry.

| Symmetry | Lie Group | Symmetry Type | Conservation Law |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poincaré | Translations×SO(3,1) | Global symmetry | Energy, Momentum, Angular momentum |

| Gauge | SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1) | Local symmetry | Electric charge, Weak isospin, Color charge |

| Baryon phase | U(1) | Accidental Global symmetry | Baryon number |

| Electron phase | U(1) | Accidental Global symmetry | Electron number |

| Muon phase | U(1) | Accidental Global symmetry | Muon number |

| Tau phase | U(1) | Accidental Global symmetry | Tau-lepton number |

List of standard model fermions

This table is based in part on data gathered by the Particle Data Group (QuarksPDF (54.8 KB)).

| Generation 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermion (left-handed) |

Symbol | Electric charge |

Weak isospin |

Weak hypercharge |

Color charge * |

Mass ** | |

| Electron |  |

|

|

|

|

511 keV | |

| Positron |  |

|

|

|

|

511 keV | |

| Electron-neutrino |  |

|

|

|

|

< 2 eV **** | |

| Up quark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 3 MeV *** | |

| Up antiquark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 3 MeV *** | |

| Down quark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 6 MeV *** | |

| Down antiquark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 6 MeV *** | |

| Generation 2 | |||||||

| Fermion (left-handed) |

Symbol | Electric charge |

Weak isospin |

Weak hypercharge |

Color charge * |

Mass ** | |

| Muon |  |

|

|

|

|

106 MeV | |

| Antimuon |  |

|

|

|

|

106 MeV | |

| Muon-neutrino |  |

|

|

|

|

< 2 eV **** | |

| Charm quark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 1.337 GeV | |

| Charm antiquark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 1.3 GeV | |

| Strange quark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 100 MeV | |

| Strange antiquark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 100 MeV | |

| Generation 3 | |||||||

| Fermion (left-handed) |

Symbol | Electric charge |

Weak isospin |

Weak hypercharge |

Color charge * |

Mass ** | |

| Tau lepton |  |

|

|

|

|

1.78 GeV | |

| Anti-tau lepton |  |

|

|

|

|

1.78 GeV | |

| Tau-neutrino |  |

|

|

|

|

< 2 eV **** | |

| Top quark |  |

|

|

|

|

171 GeV | |

| Top antiquark |  |

|

|

|

|

171 GeV | |

| Bottom quark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 4.2 GeV | |

| Bottom antiquark |  |

|

|

|

|

~ 4.2 GeV | |

Notes:

|

|||||||

Tests and predictions

The Standard Model predicted the existence of W and Z bosons, the gluon, the top quark and the charm quark before these particles had been observed. Their predicted properties were experimentally confirmed with good precision.

The Large Electron-Positron Collider at CERN tested various predictions about the decay of Z bosons, and found them confirmed.

To get an idea of the success of the Standard Model a comparison between the measured and the predicted values of some quantities are shown in the following table:

| Quantity | Measured (GeV) | SM prediction (GeV) |

|---|---|---|

| Mass of W boson | 80.398±0.025 | 80.3900±0.0180 |

| Mass of Z boson | 91.1876±0.0021 | 91.1874±0.0021 |

Challenges to the standard model

The Standard Model of particle physics has been empirically determined through experiments over the past fifty years. Currently the Standard Model predicts that there is one more particle to be discovered, the Higgs boson. One of the reasons for building the Large Hadron Collider is that the increase in energy is expected to make the Higgs observable. However, as of August 2008, there are only indirect experimental indications for the existence of the Higgs boson and it can not be claimed to be found.

There has been a great deal of both theoretical and experimental research exploring whether the Standard Model could be extended into a complete theory of everything. This area of research is often described by the term 'Beyond the Standard Model'. There are several motivations for this research. First, the Standard Model does not attempt to explain gravity, and it is unknown how to combine quantum field theory which is used for the Standard Model with general relativity which is the best physical model of gravity. This means that there is not a good theoretical model for phenomena such as the early universe.

Another avenue of research is related to the fact that the standard model seems very ad-hoc and inelegant. For example, the theory contains many seemingly unrelated parameters of the theory — 21 in all (18 parameters in the core theory, plus G, c and h; there are believed to be an additional 7 or 8 parameters required for the neutrino masses, although neutrino masses are outside the standard model and the details are unclear). Research also focuses on the Hierarchy problem (why the weak scale and Planck scale are so disparate), and attempts to reconcile the emerging Standard Model of Cosmology with the Standard Model of particle physics. Many questions relate to the initial conditions that led to the presently observed Universe. Examples include: Why is there a matter/antimatter asymmetry? Why is the Universe isotropic and homogeneous at large distances?

See also

- The theoretical formulation of the standard model

- Weak interactions, Fermi theory of beta decay and electroweak theory

- Strong interactions, flavour, quark model and quantum chromodynamics

- For open questions, see quark matter, CP violation and neutrino masses

- Beyond the Standard Model

- noncommutative standard model

- BTeV

- Penguin diagram

Notes

- ↑ S. Weinberg Phys. Rev.Lett. 19 1264–1266 (1967).

- ↑ "Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons".

- ↑ F. J. Hasert et al. Phys. Lett. 46B 121 (1973).

- ↑ F. J. Hasert et al. Phys. Lett. 46B 138 (1973).

- ↑ F. J. Hasert et al. Nucl. Phys. B73 1(1974).

- ↑ "The discovery of the weak neutral currents". CERN courier (2004-10-04). Retrieved on 2008-05-08.

- ↑ Technically, there are nine such color–anticolor combinations. However there is one color symmetric combination that can be constructed out of a linear superposition of the nine combinations, reducing the count to eight.

- ↑ "Higgs Hiding in Plain Sight?". ScienceNOW (2008-01-23). Retrieved on 2008-05-08.

- ↑ Particle Data Group: Neutrino mass, mixing, and flavor change (2006v)

References

Introductory textbooks

- Griffiths, David J. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. Wiley, John & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- D.A. Bromley (2000). Gauge Theory of Weak Interactions. Springer. ISBN 3-540-67672-4.

- Gordon L. Kane (1987). Modern Elementary Particle Physics. Perseus Books. ISBN 0-201-11749-5.

Advanced textbooks

- Cheng, Ta Pei; Li, Ling Fong. Gauge theory of elementary particle physics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-851961-3.

- — introduction to all aspects of gauge theories and the Standard Model.

- Donoghue, J. F.; Golowich, E.; Holstein, B. R.. Dynamics of the Standard Model. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521476522.

- — highlights dynamical and phenomenological aspects of the Standard Model.

- O'Raifeartaigh, L.. Group structure of gauge theories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34785-8.

- — highlights group-theoretical aspects of the Standard Model.

Journal articles

- S.F. Novaes, Standard Model: An Introduction, hep-ph/0001283

- D.P. Roy, Basic Constituents of Matter and their Interactions — A Progress Report, hep-ph/9912523

- Y. Hayato et al., Search for Proton Decay through p → νK+ in a Large Water Cherenkov Detector. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1529 (1999).

- Ernest S. Abers and Benjamin W. Lee, Gauge theories. Physics Reports (Elsevier) C9, 1–141 (1973).

External links

- New Scientist story: Standard Model may be found incomplete

- The Universe Is A Strange Place, a lecture by Frank Wilczek

- Observation of the Top Quark at Fermilab

- PDF version of the Standard Model Lagrangian (after electroweak symmetry breaking, with no explicit Higgs boson)

- PDF, PostScript, and LaTeX version of the Standard Model Lagrangian with explicit Higgs terms

- The particle adventure.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

,

,  )

)

,

,  )

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)