Spore

In biology, a spore is a reproductive structure that is adapted for dispersal and surviving for extended periods of time in unfavorable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, fungi and some protozoans.[1] A chief difference between spores and seeds as dispersal units is that spores have very little stored food resources compared with seeds.

Spores are usually haploid and unicellular and are produced by meiosis in the sporophyte. Once conditions are favorable, the spore can develop into a new organism using mitotic division, producing a multicellular gametophyte, which eventually goes on to produce gametes.

Two gametes fuse to create a new sporophyte. This cycle is known as alternation of generations, but a better term is "biological life cycle", as there may be more than one phase and so it cannot be a direct alternation. Haploid spores produced by mitosis (known as mitospores) are used by many fungi for asexual reproduction.

Spores are the units of asexual reproduction, because a single spore develops into a new organism. By contrast, gametes are the units of sexual reproduction, as two gametes need to fuse to create a new organism.

The term spore may also refer to the dormant stage of some bacteria or archaea; however these are more correctly known as endospores and are not truly spores in the sense discussed in this article. The term can also be loosely applied to some animal resting stages. Fungi that produce spores are known as sporogenous, and those that do not are asporogenous.

The term derives from the ancient Greek word σπορα ("spora"), meaning a seed.

Contents |

Classification

Spores can be classified in several ways:

By spore-producing structure

In fungi and fungus-like organisms, spores are often classified by the structure in which meiosis and spore production occurs. Since fungi are often classified according to their spore-producing structures, these spores are often characteristic of a particular taxon of the fungi.

- Sporangiospores: spores produced by a sporangium in many fungi such as zygomycetes.

- Zygospores: spores produced by a zygosporangium, characteristic of zygomycetes.

- Ascospores: spores produced by an ascus, characteristic of ascomycetes.

- Basidiospores: spores produced by a basidium, characteristic of basidiomycetes.

- Aeciospores: spores produced by a aecium in some fungi such as rusts or smuts.

- Urediospores: spores produced by a uredinium in some fungi such as rusts or smuts.

- Teliospores: spores produced by a telium in some fungi such as rusts or smuts.

- Oospores: spores produced by a oogonium, characteristic of oomycetes.

- Carpospores: spores produced by a carposporophyte, characteristic of red algae.

- Tetraspores: spores produced by a tetrasporophyte, characteristic of red algae.

By function

- Chlamydospores: thick-walled resting spores of fungi produced to survive unfavorable conditions.

By origin during life cycle

- Meiospores: spores produced by meiosis; they are thus haploid, and give rise to a haploid daughter cell(s) or a haploid individual. Examples are the precursor cells of gametophytes of seed plants found in flowers (angiosperms) or cones (gymnosperms).

- Microspores: meiospores that give rise to a male gametophyte, (pollen in seed plants).

- Megaspores (or macrospores): meiospores that give rise to a female gametophyte, (an ovule in seed plants).

- Mitospores (or conidia, conidiospores): spores produced by mitosis; they are characteristic of Ascomycetes. Fungi in which only mitospores are found are called “mitosporic fungi” or “anamorphic fungi”, and are previously classified under the taxon Deuteromycota (See Teleomorph, anamorph and holomorph).

By motility

Spores can be differentiated by whether they can move or not.

- Zoospores: mobile spores that move by means of one or more flagella, and can be found in some algae and fungi.

- Aplanospores: immobile spores that may nevertheless potentially grow flagella.

- Autospores: immobile spores that cannot develop flagella.

- Ballistospores: spores that are actively discharged from the body of the fungal fruiting body. Most basidiospores are also ballistospores, and another notable example is spores of Pilobolus.

- Statismospores: spores that are not actively discharged from the fungal fruiting body. Examples are puffballs.

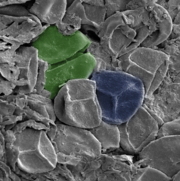

Trilete spores

-shaped scar. The spores are about 30-35 μm across.

-shaped scar. The spores are about 30-35 μm across.Trilete spores, formed by the dissociation of a spore tetrad, are taken as the earliest evidence of life on land,[2] dating to the mid-Ordovician (early Llanvirn, ~).[3]

Parlance

In common parlance, the difference between a "spore" and a "gamete" (both together called gonites) is that a spore will germinate and develop into a sporeling, while a gamete needs to combine with another gamete before developing further. However, the terms are somewhat interchangeable when referring to gametes.

A chief difference between spores and seeds as dispersal units is that spores have little food storage compared with seeds, and thus require more favorable conditions in order to successfully germinate. (This is not without its exceptions, however: many orchid seeds, although multicellular, are microscopic and lack endosperm, and spores of some fungi in the Glomeromycota commonly exceed 300µm in diameter.)[4] Seeds, therefore, are more resistant to harsh conditions and require less energy to start mitosis. Spores are produced in large numbers to increase the chance of a spore surviving in a number of notable examples.

The endospores of certain bacteria are often simply called "spores," as seen in the 2001 anthrax attacks, where the media called anthrax endospores "anthrax spores." Unlike eukaryotic spores, endospores are primarily a survival mechanism, not a reproductive method, and a bacterium only produces a single endospore.

Diaspores

In the case of spore-shedding vascular plants such as ferns, wind distribution of very light spores provides great capacity for dispersal. Also, spores are less subject to animal predation than seeds because they contain almost no food reserve; however they are more subject to fungal and bacterial predation. Their chief advantage is that, of all forms of progeny, spores require the least energy and materials to produce.

Vascular plant spores are always haploid and vascular plants are either homosporous or heterosporous. Plants that are homosporous produce spores of the same size and type. Heterosporous plants, such as spikemosses, quillworts, and some aquatic ferns produce spores of two different sizes: the larger spore in effect functioning as a "female" spore and the smaller functioning as a "male".

Under high magnification, spores can be categorized as either monolete spores or trilete spores. In monolete spores, there is a single line on the spore indicating the axis on which the mother spore was split into four along a vertical axis. In trilete spores, all four spores share a common origin and are in contact with each other, so when they separate, each spore shows three lines radiating from a center pole.

Parasitic Fungal spores

Parasitic fungal spores may be classified into internal spores, which germinate within the host, and external spores, also called environmental spores, released by the host to infest other hosts.[5]

See also

- A video of spores being ejected by fungus

- Alternation of generations

- Bioaerosol

- Sporophyte

- Endospore

- Fern

- Auxiliary cell

References

- ↑ Spore FAQ - Aerobiology Research Laboratory

- ↑ Gray, J. (1985). "The Microfossil Record of Early Land Plants: Advances in Understanding of Early Terrestrialization, 1970-1984". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (1934-1990) 309 (1138): 167–195. doi:. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0080-4622(19850402)309%3A1138%3C167%3ATMROEL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-E. Retrieved on 2008-04-26.

- ↑ Wellman, C.H., Gray, J. (2000). "The microfossil record of early land plants". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 355 (1398): 717–732. doi:. http://www.journals.royalsoc.ac.uk/index/2NWB35JF2C34PJHG.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-02-13.

- ↑ INVAM

- ↑ [1].

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||