Space Shuttle program

NASA's Space Shuttle, officially called Space Transportation System (STS), is the United States government's current manned launch vehicle. The winged Space Shuttle orbiter is launched vertically, usually carrying five to seven astronauts (although eight have been carried) and up to 50,000 lb (22 700 kg) of payload into low earth orbit. When its mission is complete, the shuttle can independently move itself out of orbit (by means of its maneuvering thrusters) and re-enter the Earth's atmosphere. During descent and landing, the orbiter acts as a glider and makes a completely unpowered landing.

The shuttle is the only winged manned spacecraft to achieve orbit and land, and the only reusable space vehicle that has ever made multiple flights into orbit. Its missions involve carrying large payloads to various orbits (including segments to be added to the International Space Station), providing crew rotation for the International Space Station, and performing service missions. The orbiter can also recover satellites and other payloads from orbit and return them to Earth, but its use in this capacity is rare. However, the shuttle has previously been used to return large payloads from the ISS to Earth, as the Russian Soyuz spacecraft has limited capacity for return payloads. Each vehicle was designed with a projected lifespan of 100 launches, or 10 years' operational life.

The program started in the late 1960s and has dominated NASA's manned operations since the mid-1970s. According to the Vision for Space Exploration, use of the space shuttle will be focused on completing assembly of the ISS by 2010, after which it will be retired from service, and eventually replaced by the new Orion spacecraft (now expected to be ready in about 2014).

Contents |

Conception

Even before the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, NASA began early studies of space shuttle designs. The early studies beginning in October, 1968 were denoted "Phase A." Further studies resulted in "Phase B" in June 1970. These plans were much more detailed and more specific.

In 1969 President Richard Nixon formed the Space Task Group, chaired by vice president Spiro T. Agnew. This group evaluated the shuttle studies to date, and recommended a national space strategy including building a space shuttle.[1]

In October 1969, at a space shuttle symposium held in Washington, George Mueller (NASA's deputy administrator) presented opening remarks:[1]

The goal we have set for ourselves is the reduction of the present costs of operating in space from the current figure of $1,000 a pound for a payload delivered in orbit by the Saturn V, down to a level of somewhere between $20 and $50 a pound. By so doing we can open up a whole new era of space exploration. Therefore, the challenge before this symposium and before all of us in the Air Force and NASA in the weeks and months ahead is to be sure that we can implement a system that is capable of doing just that. Let me outline three areas which, in my view, are critical to the achievement of these objectives. One is the development of an engine that will provide sufficient specific impulse, with adequate margin to propel its own weight and the desired payload. A second technical problem is the development of the reentry heat shield, so that we can reuse that heat shield time after time with minimal refurbishment and testing. The third general critical development area is a checkout and control system which provides autonomous operation by the crew without major support from the ground and which will allow low cost of maintenance and repair. Of the three, the latter may be a greater challenge than the first two.

The 1972 NASA/GAO REPORT TO THE CONGRESS, Cost-Benefit Analysis Used In Support Of The Space Shuttle Program states:[2]

NASA has proposed that a space shuttle be developed for U.S. Space Transportation needs for NASA, the Department of Defense (DOD), and other users in the 1980s. The primary objective of the Space Shuttle Program is to provide a new space transportation capability that will:

- reduce substantially the cost of space operations and

- provide a future capability designed to support a wide range of scientific, defense, and commercial uses.

Development

During early shuttle development there was great debate about the optimal shuttle design that best balanced capability, development cost and operating cost. Ultimately the current design was chosen, using a reusable winged orbiter, solid rocket boosters, and an expendable external tank.[1]

The shuttle program was formally launched on January 5, 1972, when President Nixon announced that NASA would proceed with the development of a reusable space shuttle system.[1] The final design was less costly to build and less technically ambitious than earlier fully reusable designs. The initial design parameters included a larger external fuel tank, which would have been carried to orbit, where it could be used as a section of a space station, but this idea was killed due to budgetary and political considerations.

The prime contractor for the program was North American Aviation (later Rockwell International, now Boeing), the same company responsible for building the Apollo Command/Service Module. The contractor for the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters was Morton Thiokol (now part of Alliant Techsystems), for the external tank, Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin), and for the Space shuttle main engines, Rocketdyne (now Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne, part of United Technologies).[1]

The first complete orbiter was originally planned to be named Constitution, but a massive write-in campaign from fans of the Star Trek television series convinced the White House to change the name to Enterprise.[3] Amid great fanfare, the Enterprise was rolled out on September 17, 1976, and later conducted a successful series of glide-approach and landing tests that were the first real validation of the design.

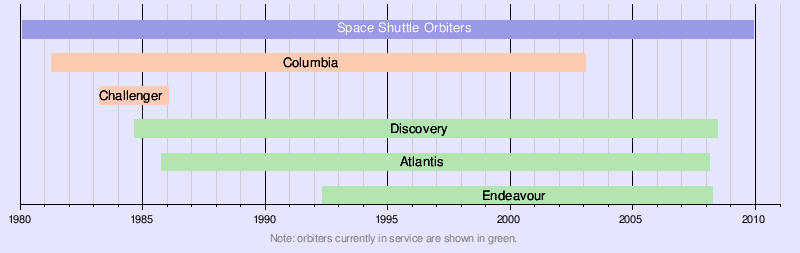

The first fully functional orbiter was the Columbia, built in Palmdale, California. It was delivered to Kennedy Space Center on March 25, 1979, and was first launched on April 12, 1981—the 20th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's space flight—with a crew of two. Challenger was delivered to KSC in July 1982, Discovery in November 1983, and Atlantis in April 1985. Challenger was destroyed during ascent due to O-Ring failure on the right SRB on January 28, 1986, with the loss of all seven astronauts on board. Endeavour was built to replace Challenger (using spare parts originally intended for the other orbiters) and delivered in May 1991; it was first launched a year later. Seventeen years after Challenger, Columbia was lost, with all seven crew members, during reentry on February 1, 2003, and has not been replaced. Out of the five fully functional shuttle orbiters built, three remain.

Shuttle applications

Current and past space shuttle applications include:

- Crew rotation and servicing of Mir and the International Space Station (ISS)

- Manned servicing missions, such as to the Hubble Space Telescope (HST)

- Manned experiments in Low Earth orbit (LEO)

- Carried to LEO:

- Large satellites — including the HST

- Components for the construction of the ISS

- Supplies in Spacehab modules or Multi-Purpose Logistics Modules

- Carried satellites with a booster, the Payload Assist Module (PAM-D) or the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), to the point where the booster sends the satellite to:

- A higher Earth orbit; these have included:

- Chandra X-ray Observatory

- Many TDRS satellites

- Two DSCS-III (Defense Satellite Communications System) communications satellites in one mission

- A Defense Support Program satellite

- An interplanetary orbit; these have included:

- Magellan probe

- Galileo spacecraft

- Ulysses probe

- A higher Earth orbit; these have included:

Flight statistics

| Shuttle | Flight days | Orbits | Distance | Flights [4] | Longest flight (in days) |

Crews | EVAs | Mir/ISS docking |

Satellites deployed |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mi | km | |||||||||

| Columbia † | 300.74 | 4,808 | 125,204,911 | 201,497,772 | 28 | 17.66 | 160 | 7 | 0 / 0 | 8 |

| Challenger † | 62.41 | 995 | 25,803,940 | 41,527,416 | 10 | 8.23 | 60 | 6 | 0 / 0 | 10 |

| Discovery | 296.84 | 4,671 | 115,140,673 | 185,300,951 | 35 | 15.39 | 209 | 39 | 1 / 8 | 31 |

| Atlantis | 245.58 | 3,873 | 89,533,755** | 144,090,611** | 29 | 13.84 | 174 | 25 | 7 / 8 | 14 |

| Endeavour | 219.35 | 3,461 | 90,347,054 | 145,399,490 | 22 | 16.63 | 137 | 33 | 1 / 7 | 3 |

| Total | 1137.17 | 17,808 | 446,030,333** | 717,816,240** | 123 | — | 830 | 113 | 9 / 23 | 66 |

(as of 21 August, 2007)

** Information for STS-117 not yet available, last updated 22 December 2006. Information for STS-118 not included either, 5,274,977 mi (8,489,253 km) as of _______. Info for STS-126 also not availible.

† No longer in service (destroyed).

Other shuttles

| Shuttle | Flight Days | Orbits | Distance -mi- |

Distance -km- |

Flights | Longest flight -days- |

Crew and passengers |

EVAs | Hubble repairs | Mir/ISS docking |

Satellites deployed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise | 0.014 | 0 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | 0.004 | >3 | 0 | 0 / 0 | 0 |

Disasters

As of April 2008, two shuttles have been destroyed in 123 missions, both with the loss of the entire crew (14 astronauts total):

- Challenger — lost 73 seconds after liftoff, STS-51-L, January 28, 1986

- Further information: Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

- Columbia — lost approximately 16 minutes before its expected landing, STS-107, February 1, 2003

- Further information: Space Shuttle Columbia disaster

This gives a 2% death rate per astronaut-flight, and an average failure rate of nearly 1 in every 60 missions. The original disaster potential, though disaster is not defined as fatal or non-fatal, was estimated during shuttle development at one every 75 missions. 87 successful missions were flown between STS-51-L and STS-107.

Current status

From September 2005 until early 2008, the manager of the space shuttle program was Wayne Hale. Hale then became NASA's deputy associate administrator for strategic partnerships. John Shannon, who had been Hale's deputy since November 2005, succeeded him as the Space Shuttle Program Manager.[5]

After the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, the International Space Station operated on a skeleton crew of two for more than two years and was serviced primarily by Russian spacecraft. While the "Return to Flight" mission STS-114 in 2005 was successful, a similar piece of foam from a different portion of the tank was shed. Although the debris did not strike the orbiter, the program was grounded once again for this reason.

The second "Return to Flight" mission, STS-121 launched on July 4, 2006, at 2:37 p.m. (EDT). Two previous launches were scrubbed because of lingering thunderstorms and high winds around the launch pad, and the launch took place despite objections from its chief engineer and safety head. A five-inch (13 cm) crack in the foam insulation of the external tank gave cause for concern; however, the Mission Management Team gave the go for launch.[6] This mission increased the ISS crew to three. Discovery touched down successfully on July 17, 2006 at 9:14 a.m. (EDT) on Runway 15 at Kennedy Space Center.

Following the success of STS-121, nine missions have been completed without major foam problems, and the construction of ISS has resumed. (During the STS-118 mission in August 2007, the orbiter was again struck by a foam fragment on liftoff, but this was a very small damage compared to the damage sustained to Columbia.)

On October 31, 2006, NASA announced approval of a shuttle servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope. This mission is designated STS-125 and is scheduled for launch in May 2009.

Retirement

The shuttle program is scheduled for mandatory retirement in 2010. The shuttle's planned successor is Project Constellation with its Ares I and Ares V launch vehicles and the Orion Spacecraft. NASA plans to launch 7 to 9 more shuttle missions before the program ceases. [7][8]

In an internal e-mail apparently sent August 18, 2008 to NASA managers and leaked to the press (published September 6, 2008 in the Orlando Sentinel, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin stated his belief that the current US administration has made no viable plan for U.S. crews to participate in the International Space Station beyond 2011, and that OMB and OSTP are actually seeking its demise.[9][10] The email appeared to suggest that Griffin believed the only reasonable solution was to extend the operation of the shuttle beyond 2010, but noted that Executive Policy (ie, the White House) is firm that there will be no extension of the shuttle retirement date, and thus no US capability to launch crews into orbit until the Ares I/Orion system becomes operational in 2014 at the very earliest. He appeared to indicate that he did not see purchase of Russian launches for NASA crews as politically viable following the 2008 South Ossetia war, and hoped the new US administration will resolve the issue in 2009 by extending shuttle operations beyond 2010.[9]

On September 7, 2008, NASA released a statement regarding the leaked email, in which Griffin said:

"The leaked internal email fails to provide the contextual framework for my remarks, and my support for the administration's policies. Administration policy is to retire the space shuttle in 2010 and purchase crew transport from Russia until Ares and Orion are available. The administration continues to support our request for an INKSNA exemption. Administration policy continues to be that we will take no action to preclude continued operation of the International Space Station past 2016. I strongly support these administration policies, as do OSTP and OMB."

—Michael D. Griffin, [11]

NASA Authorization Act of 2008

U.S. Representative Dave Weldon has introduced H.R. 4837, known as the SPACE Act.[12] This legislation would keep the shuttle flying past 2010 at a reduced rate until the Orion spacecraft is ready to replace it. It would allow both the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer as well as the completed-but-unused Centrifuge Accommodations Module to be launched to the ISS, which the current schedule does not allow.[13]

On October 15, 2008, President Bush signed the NASA Authorization Act of 2008, giving NASA funding for one additional mission to "deliver science experiments to the station".[14][15][16][17] The Act allows for an additional space shuttle flight, STS-134, to the ISS to install the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, which was previously canceled.[18]

Costs

The total cost of the shuttle program has been $145 billion USD as of early 2005, and is estimated to be $174 billion when the shuttle retires in 2010. NASA's budget for 2005 allocated 30%, or $5 billion, to space shuttle operations;[19] this was decreased in 2006 to a request of $4.3 billion.[20]

Per-launch costs can be measured by dividing the total cost over the life of the program (including buildings, facilities, training, salaries, etc) by the number of launches. With 115 missions (as of 6 August 2006), and a total cost of $150 billion ($145 billion as of early 2005 + $5 billion for 2005,[19] this gives approximately $1.3 billion per launch. Another method is to calculate the incremental (or marginal) cost differential to add or subtract one flight — just the immediate resources expended/saved/involved in that one flight. This is about $60 million U. S. dollars.[21]

Early cost estimates of $118 per pound ($260/kg) of payload were based on marginal or incremental launch costs, and based on 1972 dollars and assuming a 65,000 pound (30 000 kg) payload capacity.[22][23] Correcting for inflation, this equates to roughly $36 million incremental per launch costs. Compared to this, today's actual incremental per launch costs are about two thirds more, or $60 million per launch.

Criticism

The space shuttle program has been criticized for failing to achieve its promised cost and utility goals, as well as design, cost, management, and safety issues.[24]

After both the Challenger disaster and the Columbia disaster, high profile boards convened to investigate the accidents with both committees returning praise and serious critiques to the program and NASA management. One of the most famous of these criticisms came from Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman.

Terrestrial transportation vehicles

- The Crawler-Transporter carries the Mobile Launcher Platform and the space shuttle from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Complex 39.

- The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft are two modified Boeing 747s. Either can fly an orbiter from alternative landing sites back to Cape Canaveral.

- A 36-wheeled transport trailer, the Orbiter Transfer System, originally built for the U.S. Air Force's launch facility at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California (since then converted for Delta IV rockets) that would transport the orbiter from the landing facility to the launch pad, which allowed both "stacking" and launch without utilizing a separate VAB-style building and crawler-transporter roadway. Prior to the closing of the Vandenberg facility, orbiters were transported from the OPF to the VAB on its undercarriage, only to be raised when the orbiter was being lifted for attachment to the SRB/ET stack. The trailer allows the transportation of the orbiter from the OPF to either the SCA-747 "Mate-Demate" stand or the VAB without placing any additional stress on the undercarriage.

- The Crew Transport Vehicle (CTV), a modified airport "People Mover", is used to assist astronauts to egress from the orbiter after landing. Upon entering the CTV, astronauts can take off their launch and re-entry suits then proceed to chairs and beds for medical checks before being transported back to the crew quarters in the Operations and Checkout Building.

- The Astrovan is used to transport astronauts from the crew quarters in the Operations and Checkout Building to the launch pad on launch day. It is also used to transport astronauts back again from the Crew Transport Vehicle at the Shuttle Landing Facility.

See also

|

Fiction

Physics

|

Similar spacecraft

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Heppenheimer, T.A. The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA's Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1999.

- ↑ General Accounting Office. Cost Benefit Analysis Used in Support of the Space Shuttle Program. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office, 1972.

- ↑ Brooks, Dawn The Names of the Space Shuttle Orbiters. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Accessed July 26, 2006.

- ↑ "Space Shuttle Flights by Orbiter publisher=NASA". Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "NASA Selects New Deputy Associate Administrator of Strategic Partnerships and Space Shuttle Program Manager". NASA.

- ↑ Chien, Philip (June 27, 2006) "NASA wants shuttle to fly despite safety misgivings." The Washington Times

- ↑ [http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/structure/iss_manifest.html NASA -Consolidated Launch Manifest

- ↑ National Aeronautics and Space Administration. "NASA Names New Rockets, Saluting the Future, Honoring the Past" Press Release 06-270. 30 June 2006.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Michael Griffin (Attributed) (2008). "Internal NASA email from NASA Administrator Griffin". SpaceRef.com. Retrieved on November 25, 2008.

- ↑ Malik, Tariq (2008). "NASA Chief Vents Frustration in Leaked E-mail". Space.com. Retrieved on November 6, 2008.

- ↑ NASA (September 7, 2008). "Statement of NASA Administrator Michael Griffin on Aug. 18 Email". Press release.

- ↑ "HR 4837 Spacefaring Priorities for America's Continued Exploration Act". Retrieved on 2008-03-28.

- ↑ "H.R. 4837: Space Act (GovTrack.us)". Retrieved on 2008-03-28.

- ↑ "To authorize the programs of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.". Library of Congress (2008). Retrieved on October 25, 2008.

- ↑ Berger, Brian (June 19, 2008). "House Approves Bill for Extra Space Shuttle Flight". Space.com. Retrieved on October 25, 2008.

- ↑ NASA (September 27, 2008). "House Sends NASA Bill to President's Desk". Spaceref.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-23.

- ↑ Matthews, Mark (October 15, 2008). "Bush signs NASA authorization act". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved on October 25, 2008.

- ↑ Berger, Brian for Space.com (September 23, 2008). "Obama backs NASA waiver, possible shuttle extension". USA Today. Retrieved on November 6, 2008.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 David, Leonard (11 February 2005). "Total Tally of Shuttle Fleet Costs Exceed Initial Estimates", Space.com. Retrieved on 2006-08-06.

- ↑ Berger, Brian (7 February 2006). "NASA 2006 Budget Presented: Hubble, Nuclear Initiative Suffer", Space.com. Retrieved on 2006-08-06.

- ↑ The Inflation Calculator

- ↑ NASA (2003) Columbia Accident Investigation Board Public Hearing Transcript

- ↑ Comptroller General (1972). "Report to the Congress: Cost-Benefit Analylsis Used in Support of the Space Shuttle Program" (pdf). United States General Accounting Office. Retrieved on November 25, 2008.

- ↑ A Rocket to Nowhere, Maciej Ceglowski, Idle Words, 8 March 2005.

Further reading

- Shuttle Reference manual

- Orbiter Vehicles

- Shuttle Program Funding 1992 - 2002

- NASA Space Shuttle News Reference - 1981 (PDF document)

- R. A. Pielke, Space Shuttle Value open to Interpretation, Aviation Week Magazine, issue 26. July 1993, p.57 (.pdf)

External links

- Official NASA Mission Site

- NASA Johnson Space Center Space Shuttle Site

- Official Space Shuttle Mission Archives

- NASA Space Shuttle Multimedia Gallery & Archives

- Shuttle audio, video, and images – searchable archives from STS-67 (1995) to present

- Kennedy Space Center Media Gallery – searchable video/audio/photo gallery

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the Space Shuttle

- U.S. Space Flight History: Space Shuttle Program

- Weather criteria for Shuttle launch

- Consolidated Launch Manifest: Space Shuttle Flights and ISS Assembly Sequence

- USENET posting - Unofficial Space FAQ by Jon Leech

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||