South Vietnam

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- "RVN" redirects here. RVN is also the former callsign of a TV station in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Australia.

South Vietnam refers to an internationally recognized state which governed Vietnam south of the 17th parallel until 1975. Its capital was Saigon and its origin can be traced to the French colony of Cochinchina, which consisted of the southern third of Vietnam. After World War II, the French reestablished this colony and then proclaimed it a republic in June 1946. When former emperor Bảo Đại agreed to serve as head of state in 1949, the name was changed to State of Vietnam. The Bảo Đại government received international recognition in 1950. American support began in 1950 and gradually replaced French. Communists led by Hồ Chí Minh gained control of North Vietnam and set up a rival government based in Hanoi following the Geneva Conference in 1954. Bảo Đại was deposed in 1955 and a "Republic of Vietnam" with Catholic leader Ngô Đình Diệm as president was proclaimed. After Diệm was deposed in a military coup in 1963, there was a series of short-lived military governments. General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu led the country from 1967 until 1975. The Vietnam War began in 1959 with an uprising by Vietcong forces supplied by North Vietnam. Fighting climaxed during the Tet Offensive of 1968, when there were 500,000 U.S. soldiers in South Vietnam. Despite a peace treaty concluded in January 1973, fighting continued until the North Vietnamese army overran Saigon in April 1975.

- 1946-47: Republic of Cochinchina

- 1947-48: Republic of South Vietnam[1]

- 1948-49: Provisional Central Government of Vietnam

- 1949–55: State of Vietnam.

- 1955–75: the Republic of Vietnam.

Contents |

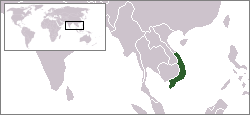

Location

South Vietnam, officially the State of Vietnam, (Vietnamese: Quốc gia Việt Nam) from 1949 to 1955, the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), (Vietnamese: Việt Nam Cộng Hòa) from 1955 to 1975, and the Republic of South Vietnam (Vietnamese: Cộng Hòa Miền Nam Việt Nam) from 1975 to 1976, was a country that existed from 1949 to 1975 in the territory of Vietnam that lay south of the 17th parallel.

History

Founding: the Nation of Vietnam

- See also: Geneva Conference (1954), Operation Passage to Freedom, and 1955 State of Vietnam referendum

Unlike the rest of French Indochina, Cochinchina, the southern third of Vietnam, was a colony rather than a protectorate. It had been annexed by France in 1862, and even elected a deputy to the French National Assembly. French interests were stronger in Cochinchina than in other parts of French Indochina. In 1946, France declared Cochinchina a republic within an Indochinese Federation. In 1949, this republic was united with the Central and North regions to form the State of Vietnam.

The State of Vietnam was created through co-operation between anti-communist Vietnamese and the French government on June 14, 1949 during the French Indochina War, and the Emperor Bao Dai took up the position of Chief of State (Quoc Truong). This was known as the 'Bao Dai Solution', and was an attempt by the French to grant partial independence to Vietnam, while still retaining substantial control over the country, and keeping it from communist rule. Such a formulation was rejected by the communist Vietminh, led by Ho Chi Minh, who were fighting the French for full independence for Vietnam.

In 1954, France and the Vietminh agreed at the Geneva Conference that the State of Vietnam would rule the territory south of the 17th parallel, pending unification on the basis of supervised elections in 1956. At the time of the conference, it was expected that the South would continue to be a French dependency. However, South Vietnamese Premier Ngô Ðình Diệm, who preferred American sponsorship to French, rejected the agreement. When Vietnam was divided, 800,000 to 1 million North Vietnamese, mainly but not exclusively Roman Catholics, sailed south (Operation Passage to Freedom) due to a fear of religious persecution in the North, which turned out to be well-founded.

1955–1963

- See also: 1955 State of Vietnam referendum and Battle for Saigon

In July 1955, Diệm announced in a broadcast that South Vietnam would not participate in the elections specificed in the Geneva accords.[2] As Saigon's delegation did not sign the Geneva accords, it was not bound by it, Diệm said.[2] He also claimed the communist government in the North created conditions that made a fair election impossible in that region.

Diệm held a referendum in October 1955 to determine the future of the country. He asked voters to approve a Republic, thus removing Bảo Ðại as head of state. The poll was supervised and rigged by his younger brother Ngo Dinh Nhu. Diệm's Republic was said to have been approved by 98 percent of voters. In many districts, there were more votes to remove Bảo Ðại than there were registered voters. In Saigon, 133 percent of the registered population reportedly voted to remove Bảo Ðại. On October 26, Diệm declared himself as the president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Vietnam. The French, who needed troops to fight in Algeria, completely withdrew from Vietnam by April 1956.[3]

Diệm attempted to consolidate his rule on Vietnam by eliminating rival groups. He launched an Anti-communist denunciation campaign (To Cong) against remnants of the communist Vietminh. He also crushed rival factions by launching military campaigns against the three main sects; the Cao Dai, Hoa Hao and the Binh Xuyen organised crime syndicate whose military strength combined amounted to approximately 350,000 soldiers. Throughout this period the level of U.S. aid and political support increased.

1963–1973

See Vietnam War for military history of the Republic of Vietnam in this period.

1973–1975

In accordance with the Paris Peace Accords signed with North Vietnam on January 27, 1973, U.S. military forces withdrew from South Vietnam. North Vietnam was allowed to continue supplying communist troops in the South, but only to the extent of replacing materials that were consumed.

The communist leaders had expected that the ceasefire terms would favor their side. But as Saigon began to roll back the Vietcong, they found it necessary to adopt a new strategy, hammered out at a series of meetings in Hanoi in March 1973, according to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà. As the Vietcong's top commander, Trà participated in several of these meetings. A plan to improve logistics was prepared so that the North Vietnamese army would be able to launch a massive invasion of the South, projected for 1976, before Saigon's army could be fully trained. A gas pipeline would be built from North Vietnam to Vietcong headquarters in Loc Ninh, about 60 miles (97 km) north of Saigon.

On March 15, 1973, U.S. President Richard Nixon implied that the U.S. would intervene militarily if the communist side violated the ceasefire. Public reaction was unfavorable and on June 4, 1973 the U.S. Senate passed the Case-Church Amendment to prohibit such intervention. The oil price shock of October 1973 caused significant damage to the South Vietnamese economy. The Vietcong resumed offensive operations and by January 1974 it had recaptured the territory that it had lost earlier. After two clashes that left 55 South Vietnamese soldiers dead, President Thieu announced on January 4 that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accord was no longer in effect. There were over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period.[4]

In August 1974, Nixon was forced to resign as a result of the Watergate scandal and the U.S. Congress voted to reduce assistance to South Vietnam from $1 billion a year to $700 million. By this time, Ho Chi Minh Trail, once an arduous mountain trek, had been upgraded into a drivable highway with gas stations.

In 1975 the communists of North Vietnam launched an offensive in the South, which became known as the Ho Chi Minh Campaign. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam unsuccessfully attempted a defense and a counterattack. It had few remaining operational tanks and artillery pieces, as well as a shortage of spare parts, and ammunition. The NVA had a vastly greater supply of new equipment and ammunition. As a consequence, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu was forced to withdraw key army units from the Central Highlands, which exacerbated an already-perilous military situation and undercut the confidence of the ARVN soldiers in their leadership.

The retreat became a rout. The cities of Huế, Da Nang and Da Lat in central Vietnam quickly fell, and the North Vietnamese advanced southwards. As the military situation deteriorated, ARVN troops started deserting.

Thieu requested aid from U.S. President Gerald Ford, but the U.S. Senate would not release extra money to provide aid to South Vietnam, and had already passed laws to prevent further involvement in Vietnam. In desperation, Thieu called back Nguyen Cao Ky from retirement as a military commander, but resisted calls to name his old rival prime minister.

Fall of Saigon, April 1975

Nguyen Van Thieu resigned on April 21, 1975, and fled to Taiwan. He nominated his Vice President Tran Van Huong as his successor. A last-ditch defense was made by the ARVN 18th Division at the Battle of Xuan Loc led by Major General Le Minh Dao. After only one week in office, Tran Van Huong handed over the presidency to General Duong Van Minh. Minh was seen as a more conciliatory figure toward the North, and it was hoped he might be able to negotiate a more favorable settlement to end the war. The North was not interested in negotiations, however, and its tanks rolled into Saigon largely unopposed which led to the fall of Saigon. Acting President Minh unconditionally surrendered the capital city of Saigon and the rest of South Vietnam to North Vietnam on April 30, 1975.

During the hours leading up to the surrender, the United States undertook a massive evacuation of its embassy in Saigon, Operation Frequent Wind. The evacuees included U.S. government personnel as well as high-ranking members of the ARVN and other South Vietnamese who had aided the U.S.-backed administration and were seen as potential targets for persecution by the Communists. Many of the evacuees were taken directly by helicopter to multiple aircraft carriers waiting off the coast. An iconic image of the evacuation is the widely-seen footage of empty Huey helicopters being jettisoned over the side of the carriers, to provide more room on the ship's deck for more evacuees to land. The evacuation was forced to stop by the U.S. Navy. All the marines and diplomats were evacuated, but thousands of South Vietnamese waited vainly atop the U.S. Embassy for helicopters that never came.

Relationship with America

The history of the relationship with the United States is controversial. Some historians say the founding of South Vietnam was based on the United States' desire to create an "anti-communist" base in Southeast Asia. Opponents argue that it was based on popular support of the South Vietnamese people. However, the U.S. and the Diem government agreed that elections mandated by the Geneva Conference (1954) should not occur, claiming that the communists could not be trusted to conduct a fair election in the North. Moreover, most contemporary observers, including U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, estimated that if an election were held in the 1954–55 period (when South Vietnam was under Bao Dai's rule), around 80% of the Vietnamese population would vote for Ho Chi Minh.[5] The dominant political rationale for supporting the South Vietnamese government was America's containment policy, which was designed to hold back the spread of communism during the Cold War.

The failure to unify the country in 1956, along with Diem's persecution of communists, led in 1959 to the foundation of the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (abbrievated NLF but also known as the Viet Cong), which initiated an organised and widespread guerrilla insurgency against the South Vietnamese government. Although initially cautious, Hanoi backed the insurgency, which grew in support and intensity. The United States, under President Eisenhower, initially sent military advisers to train the South Vietnamese army. President John F. Kennedy increased the size of the advisory force fourfold and allowed the advisors to participate in combat operations, and later acquiesced in the removal of President Diem in a military coup. After promising not to do so during the 1964 election campaign, in 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to send in much larger numbers of combat troops, and conflict steadily escalated to become what is commonly known as the Vietnam War. In 1968, the NLF ceased to be an effective fighting organization after the Tet Offensive and the war was largely taken over by regular army units of North Vietnam. Following American withdrawal from the war in 1973, the South Vietnamese government continued fighting the North Vietnamese, until, overwhelmed by a conventional invasion by the North, it finally unconditionally surrendered on April 30, 1975, the day of the surrender of Saigon. North Vietnam controlled South Vietnam under military occupation, while the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam, which had been proclaimed in June 1969 by the NLF, established the Republic of South Vietnam but the republic never really had any of the authority of a government. The North Vietnamese quickly moved to marginalise non-communist members of the PRG and integrate South Vietnam into the communist north. The unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam was inaugurated on July 2, 1976.

Controversial history

| History of Vietnam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There is much controversy about how closely the South Vietnamese government was linked to the United States. While it is clear that Ngo Dinh Diem was initially the favored candidate of the United States to rule South Vietnam, he later displayed a sufficiently independent and nationalistic streak that the American government assented to his removal by a coup.

It has been claimed that, in particular, the South Vietnamese government of Nguyen Van Thieu was nothing more than an American puppet, and point to American connivance in Thieu's manipulation of the 1971 South Vietnamese Presidential election as evidence. On the other hand, some point to sharp differences between Thieu and Nixon at the time of the Paris Peace Accord to demonstrate that he was not a puppet. The historical consensus is that there existed a symbiotic relationship between the Thieu government and US military involvement in Indochina: without American support the Thieu government could not survive; while the US needed to maintain the Thieu government to be able to continue its involvement in Indochina. The removal of one of these factors would inevitably bring about the end of the other.

Politics

- See also: 1955 South Vietnamese election, 1963 South Vietnamese coup, Arrest and assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem, and 1964 South Vietnamese coup

South Vietnam went through many political changes during its short life. Initially, the nation was a constitutional monarchy, with Emperor Bao Dai as Head of State. The Vietnamese monarchy was unpopular however, largely because monarchical leaders were considered collaborators during French rule.

In 1955 a republican referendum, which is largely considered to have been rigged due to the active presence of pro-republican military forces at voting booths, ended with a 98% vote in favour of abolishing the monarchy. In Saigon, Diem received 133% of the vote. This abolished the monarchy and made Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem the country's first president. Despite successes in politics, economics, and social change in the first 5 years, Diem quickly became a dictatorial leader. With the acquiescence of the United States government, ARVN officers led by General Duong Van Minh staged a coup and killed him in 1963. The military held a brief interim government until General Nguyen Khanh deposed Minh in a January 1964 coup. Until late 1965, multiple coups and changes of government occurred, with some civilians being allowed to give a semblance of legislative rule overseen by a military junta.

In 1965 the feuding civilian government voluntarily resigned and handed power back to the nation's military, in the hope this would bring stability and unity to the nation. A joint assembly with representatives of all the branches of the military decided to switch the nation's system of government to a parliamentary system with a strong Prime Minister and a figurehead President. There was a bicameral National Assembly consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. Military rule initially failed to provide much stability however, as internal conflicts and political inexperience caused various factions of the army to launch coups and counter-coups against one another, making leadership very tumultuous. The situation stabilized when the Vietnam Air Force chief Nguyen Cao Ky became Prime Minister, with former General Nguyen Van Thieu as his deputy.

In 1967 South Vietnam held its first elections under the new system. Following the elections, however, it switched back to a presidential system. The military nominated Nguyen Van Thieu as their candidate, and he was elected with a plurality of the popular vote. Thieu quickly consolidated power much to the dismay of those who hoped for an era of more political openness. He was re-elected unopposed in 1971, receiving a suspiciously high 94% of the vote on an 87% turn-out. Thieu ruled until the final days of the war, resigning in 1975. Duong Van Minh was the nation's last president and unconditionally surrendered to the Communist forces a few days after assuming office.

South Vietnam was formerly a member of ACCT, Asian Development Bank (ADB), World Bank (IBRD), International Development Association (IDA), International Finance Corporation (IFC), IMF, International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (Intelsat), Interpol, IOC, ITU, League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (LORCS), UNESCO and Universal Postal Union (UPU).

Leaders of the Republic of Vietnam

- See the Leaders of South Vietnam.

- Ngo Dinh Diem (1955–1963)

- Duong Van Minh (1963–1964)

- Nguyen Khanh (1964)

- Phan Khac Suu (1964–1965)

- Nguyen Van Thieu (1965–1975)

- Tran Van Huong (1975)

- Duong Van Minh (2nd time) (1975)

Republic of South Vietnam

Following the surrender of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975, the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam established itself in Saigon as the government of the Republic of South Vietnam. However, it lacked real autonomy and was largely under the control of the North Vietnamese. The Republic of South Vietnam was dissolved in July 1976 when it merged with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) to become the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Army

On October 26, 1956, the military was reorganized by the administration of President Ngo Dinh Diem who established the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN, pronounced "arvin"). Early on, the focus of the army was combatting the guerrilla fighters of the Vietcong, or National Liberation Front, an insurgent movement supplied by North Vietnam. The United States, under President John F. Kennedy sent advisors and a great deal of financial support to aid ARVN in combating the Vietcong. ARVN and President Diem began to be criticized by the foreign press when the troops were used to crush southern religious groups like the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao as well as to raid Buddhist temples, which Diem claimed were harboring Communist guerrillas.

In 1963 Ngo Dinh Diem was killed in a coup d'état carried out by ARVN officers led by Duong Van Minh ('Big Minh'). In the confusion that followed Big Minh took power, but was only the first in a succession of ARVN generals to assume the presidency of South Vietnam in a period of intense political instability. During these years, the United States began taking full control of the war against the NLF and the role of the ARVN became less and less significant. They were also plagued by continuing problems of severe corruption among the officer corps. Although the U.S. was highly critical of them, the ARVN continued to be entirely U.S. armed and funded.

The value of the ARVN was highly questionable in this period. In 1963 at the Battle of Ap Bac some 1,400 ARVN troops were defeated by only 350 Vietcong guerrillas. The battle of Dong Xoai in 1965 was another humiliating ARVN defeat. Although they always outnumbered their nationalist enemies, most were inexperienced, poorly trained, and not motivated to fight hard for the generals and politicians behind them. Generals tended to be political appointees and corruption was rampant. Their relations with the civilian population were never good and relations with the U.S. military were often very cold.

Starting in 1969, President Richard M. Nixon started the process of "Vietnamization," pulling out American forces and leaving the ARVN to fight the war against the North Vietnamese. Slowly, ARVN began to expand from its counter-insurgency role to become the primary ground defense against the Vietcong and North Vietnamese. From 1969–1971 there were about 22,000 ARVN combat deaths per year. Starting in 1968, South Vietnam began calling up every available man for service in the ARVN, reaching a strength of a million soldiers by 1972. In 1970 they performed well in Cambodia and were executing 3 times as many operations as they had during the American war period. However, the officer corps was still the biggest problem. Leaders were often poorly trained, inept and the equipment continued to sub-standard as the U.S. tried to upgrade ARVN technology.

Relations with the public also remained poor as their only counter to Vietcong organizing was to resurrect the Strategic Hamlet Program, which many peasants resented. Disapproving Americans called this "barbed wire diplomacy." However, forced to carry the burden left by the Americans, the South Vietnamese army actually started to perform rather well, and in 1970 was winning the war against the Communists, though with continued American air support. The exhaustion of the North was becoming evident, and the Paris talks gave some hope of a negotiated peace, if not a victory.

The most crucial moment of truth for the ARVN came with General Vo Nguyen Giap's 1972 "Easter Offensive," the first all-out invasion of South Vietnam by the communist North. It was code-named "Nguyen Hue" after the historic Vietnamese hero who defeated the Chinese in 1778. The assault combined infantry wave assaults, artillery and the first massive use of tanks by the North Vietnamese. ARVN took heavy losses, but to the surprise of many, managed to hold their ground.

U.S. President Richard Nixon dispatched more bombers to provide air support for ARVN when it seemed that South Vietnam was about to be overrun. In desperation, President Nguyen Van Thieu fired the incompetent General Hoàng Xuân Lãm and replaced him with ARVN's best commander, General Ngo Quang Truong. He gave the order that all deserters would be executed and pulled enough forces together so that the North Vietnamese army failed to take Hue. Finally, largely as a result of U.S. air and naval support, as well as some surprising determination by the ARVN soldiers, the Easter Offensive was halted.

After the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973 all U.S. military forces withdrew from South Vietnam and the war officially ended, however clashes between ARVN and Vietcong forces continued.

In 1975 the North Vietnamese again invaded the South. Lacking U.S. air support the ARVN could not hold them back. City after city fell to the Communists with ARVN soldiers joining the civilians trying to flee south. The North called this the "Hồ Chí Minh Campaign." All resistance crumbled. Faced with few viable options, the South tried to form a coalition government that would be palatable to the Communists, one that favored negotiated peace and neutrality. The new coalition government was headed by General Duong Van Minh (Big Minh), one of the organizers of the coup in November 1963, with the full support of the CIA and President Kennedy, that killed President Ngo Dinh Diem. General Cao Van Vien, then Colonel and Commander of the Airborne Brigade, had been captured and held by the Big Minh faction and threatened with execution unless he ordered his troops to join the coup. He refused and was held captive until the end of the coup and was released only because of his close friendship with one of the coup leaders.

Because the new coalition government would be headed by Big Minh, General Vien immediately submitted his resignation to then President of South Vietnam Tran Van Huong, who succeeded President Thieu as President. President Huong, knowing the 1963 coup history, granted General Vien's resignation request (Vien had submitted his resignation to President Thieu many times and had always been turned down).General Vien then escaped to the US as a civilian once his resignation was effective and formalized.

The situation in South Vietnam deteriorated.

The ARVN tried to defend Xuan Loc, their last line before Saigon. These men fought very well, but it was not enough. They were greatly outnumbered and overwhelmed by the entire army of North Vietnam. Xuan Loc was taken and on April 30, 1975, initiated the Fall/Liberation of Saigon. The North Vietnamese army captured the city, placing the Vietcong flag over the Independence Palace even though the Vietcong had accomplished almost nothing during the battles and had almost no authority within the country. General Duong Van Minh, recently appointed president by Tran Van Huong, unconditionally surrendered the city and government bringing the Republic of Vietnam and also the Army of the Republic of Vietnam to a final end.

Provinces

South Vietnam's capital was Saigon which was renamed Hồ Chí Minh City on May 1, 1975 after unconditionally surrendering to the North.

Before surrendering, the South was divided into forty-four provinces (tỉnh, singular and plural).

Geography

The South was divided into coastal lowlands, the mountainous Central highlands (Cao-nguyen Trung-phan), and the Mekong River Delta.

Economy

South Vietnam maintained a free-market economy and ties to the west. It established an airline under Head of State Bao Dai named Air Vietnam. The economy was greatly assisted by American aid and the presence of large numbers of Americans in the country between 1961 and 1973. Electrical production increased fourteen-fold between 1954 and 1973 while industrial output increase by an average of 6.9 percent annually.[6] During the same period, rice output increased by 203 percent and the number of students in university increased from 2,000 to 90,000.[6] U.S. aid peaked at $2.3 billion in 1973, but dropped to $1.1 billion in 1974.[7] Inflation rose to 200 percent as the country suffered economic shock due the decrease of American aid as well as the oil price shock of October 1973.[7] The unification of Vietnam in 1976 led to the imposition of North Vietnam's centrally planned economy into the South. The country made no significant economic progress for the next twenty years. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of Soviet aid, the leadership of Vietnam accepted the need for change. Their occupation armies were withdrawn from Laos and Cambodia. Afterward, the country introduced economic reforms that created a market economy in the mid 1990s. The government remains a collective dictatorship under the close control of the communist party.

Demographics

About 90% of population was Kinh, and 10% was Hoa, Montagnard, French, Cham, Eurasians and others. (1970)

Culture

Principal religions were Buddhism, Roman Catholic, Cao Dai, Hoa Hao, animists and others.

Vietnamese culture

Cultural life was strongly influenced by China until French domination in the 19th century. At that time, the traditional culture began to acquire an overlay of western characteristics. Many families have three generations living under one roof.

See also

- Republic of Vietnam Navy

- Vietnam Air Force

- Republic of Vietnam Marine Corps

- Air Vietnam

- Civilian Irregular Defense Group

- Independence Palace

- Leaders of South Vietnam

- Vietnam

- Vietnam War

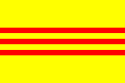

- Flag of South Vietnam

- National anthem of South Vietnam

| Preceded by State of Việt Nam |

Ruler of South Vietnam 1955 - 1975 |

Succeeded by Republic of South Việt Nam |

References

- ↑ "French Cochinchina Sept. 1945 - 1949"

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cheng Guan Ang, Vietnamese Communists' Relations with China and the Second Indochina War (1956-62) p. 11. McFarland (1997)

- ↑ The History Place - Vietnam War 1945-1960

- ↑ This Day in History 1974: Thieu announces war has resumed

- ↑ Brigham, Guerrulla Diplomacy, p. 6; Marcus Raskin & Bernard Fall, The Viet-Nam Reader, p. 89; William Duiker, U.S. Containment Policy and the Conflict in Indochina, p. 212

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kim, Youngmin, "The South Vietnamese Economy During the Vietnam War, 1954-1975"

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wiest, Andrew A., The Vietnam War, 1956-1975, p. 80.

External links

- The Constitution of the Republic of Vietnam 1956 (English language)

- HIẾN PHÁP VIỆT NAM CỘNG HOÀ 1967 (Vietnamese language)

- 1975: Saigon surrenders

- Timeline of NVA invasion of South Vietnam