Solstice

| UTC date and time of solstices and equinoxes[1] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | Equinox Mar |

Solstice June |

Equinox Sept |

Solstice Dec |

||||

| day | time | day | time | day | time | day | time | |

| 2002 | 20 | 19:16 | 21 | 13:24 | 23 | 04:55 | 22 | 01:14 |

| 2003 | 21 | 01:00 | 21 | 19:10 | 23 | 10:47 | 22 | 07:04 |

| 2004 | 20 | 06:49 | 21 | 00:57 | 22 | 16:30 | 21 | 12:42 |

| 2005 | 20 | 12:33 | 21 | 06:46 | 22 | 22:23 | 21 | 18:35 |

| 2006 | 20 | 18:26 | 21 | 12:26 | 23 | 04:03 | 22 | 00:22 |

| 2007 | 21 | 00:07 | 21 | 18:06 | 23 | 09:51 | 22 | 06:08 |

| 2008 | 20 | 05:48 | 20 | 23:59 | 22 | 15:44 | 21 | 12:04 |

| 2009 | 20 | 11:44 | 21 | 05:45 | 22 | 21:18 | 21 | 17:47 |

| 2010 | 20 | 17:32 | 21 | 11:28 | 23 | 03:09 | 21 | 23:38 |

| 2011 | 20 | 23:21 | 21 | 17:16 | 23 | 09:04 | 22 | 05:30 |

| 2012 | 20 | 05:14 | 20 | 23:09 | 22 | 14:49 | 21 | 11:11 |

| 2013 | 20 | 11:02 | 21 | 05:04 | 22 | 20:44 | 21 | 17:11 |

| 2014 | 20 | 16:57 | 21 | 10:51 | 23 | 02:29 | 21 | 23:03 |

Of the many ways in which solstice can be defined, one of the most common (and perhaps most easily understood) is by the astronomical phenomenon for which it is named, which is readily observable by anyone on Earth: a "sun-standing." This modern scientific word descends from a Latin scientific word in use in the late Roman republic of the 1st century BC: solstitium. Pliny uses it a number of times in his Natural History with the meaning it still has, but the word is in common use in other authors. It contains two Latin-language segments, sol, "sun", and -stitium, "stoppage."[2] By this "standing" the Romans meant a component of the relative velocity of the sun as it is observed in the sky. Relative velocity is the motion of an object from the point of view of an observer in a frame of reference; for example, if it is true that seen from a space ship the Earth orbits the sun, it is also true that seen from the Earth the sun orbits the Earth. Relative velocity is quite real; that is, the perceived motions of objects are entirely relative to point of view; one and the same motion appears different from different frames of reference, and there is no absolute frame of reference from which all other motions are to be described.[3]

To an observer in inertial space, perhaps in a space craft, the Earth rotates about an axis and revolves around the sun in an elliptical path with the sun at one focus. This is the point of view of writers of astronomy textbooks. The Earth's axis is tilted rather than perpendicular to the plane of the Earth's orbit and this axis maintains a position that changes little (but does change) with respect to the background of stars. An observer on Earth therefore sees a solar path that is the result of both rotation and revolution.

The component of the sun's motion seen by an Earth-bound observer caused by the revolution of the tilted axis, which, keeping the same angle in space, is oriented toward or away from the sun, is an observed diurnal increment (and lateral offset) of the elevation of the sun at noon for roughly six months and observed daily decrement for the remaining six months. At maximum or minimum elevation the relative motion at 90° to the horizon stops and changes direction by 180°. The maximum is the summer solstice and the minimum is the winter solstice. The path of the sun, or ecliptic, sweeps north and south between the northern and southern hemispheres. Around the summer solstice the days are longest and the shortest around the winter solstice. When the path crosses the equator the days and nights are of equal length, a condition called an equinox. There are two solstices and two equinoxes.[4]

The term solstice can also be used in a wider sense, as the date (day) that such a passage happens. The solstices, together with the equinoxes, are connected with the seasons. In some languages they are considered to start or separate the seasons; in others they are considered to be centre points (in English, in the Northern hemisphere, for example, the period around the June solstice is known as midsummer, and Midsummer's Day is 24 June, about three days after the solstice itself). Similarly 25 December is the start of the Christmas celebration, which was a pagan festival in pre-Christian times, and is the day the sun begins to return to the northern hemisphere.

Contents[hide] |

Names and concepts of the solstices

Ancient Greek names and concepts

The concept of the solstices was embedded in ancient Greek celestial navigation. As soon as they discovered that the Earth is spherical[5] they devised the concept of the celestial sphere,[6] an imaginary spherical surface rotating with the heavenly bodies (ouranioi) fixed in it (the modern one does not rotate, but the stars in it do). As long as no assumptions are made concerning the distances of those bodies from Earth or from each other, the sphere can be accepted as real and is in fact still in use.

The stars move across the inner surface of the celestial sphere along the circumferences of circles in parallel planes[7] perpendicular to the Earth's axis extended indefinitely into the heavens and intersecting the celestial sphere in a celestial pole.[8] The sun and the planets do not move in these parallel paths but along another circle, the ecliptic, whose plane is at an angle, the obliquity of the ecliptic, to the axis, bringing the sun and planets across the paths of and in among the stars.*

Cleomedes says:[9]

The band of the Zodiac (zōdiakos kuklos, "zodiacal circle") is at an oblique angle (loksos) because it is positioned between the tropical circles and equinoctial circle touching each of the tropical circles at one point ... This Zodiac has a determinable width (set at 8° today) ... that is why it is described by three circles: the central one is called "heliacal" (hēliakos, "of the sun").

The term heliacal circle is used for the ecliptic, which is in the center of the zodiacal circle, conceived as a band including the noted constellations named on mythical themes. Other authors use Zodiac to mean ecliptic, which first appears in a gloss of unknown author in a passage of Cleomedes where he is explaining that the moon is in the zodiacal circle as well and periodically crosses the path of the sun. As some of these crossings represent eclipses of the moon, the path of the sun is given a synonym, the ekleiptikos (kuklos) from ekleipsis, "eclipse."

English names

The two solstices can be distinguished by different pairs of names, depending on which feature one wants to stress.

- Summer solstice and winter solstice are the most common names. However, these can be ambiguous since seasons of the northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere are opposites, and the summer solstice of one hemisphere is the winter solstice of the other. These are also known as the 'longest' or 'shortest' days of the year.

- Northern solstice and southern solstice indicate the direction of the sun's apparent movement. The northern solstice is in June on Earth, when the sun is directly over the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere, and the southern solstice is in December, when the sun is directly over the Tropic of Capricorn in the Southern Hemisphere.

- June solstice and December solstice are an alternative to the more common "summer" and "winter" terms, but without the ambiguity as to which hemisphere is the context. They are still not universal, however, as not all people use a solar-based calendar where the solstices occur every year in the same month (as they do not in the Islamic Calendar and Hebrew calendar, for example), and the names are not useful for other planets (Mars, for example), even though these planets do have seasons.

- First point of Cancer and first point of Capricorn. One disadvantage of these names is that, due to the precession of the equinoxes, the astrological signs where these solstices are located no longer correspond with the actual constellations.

- Taurus solstice and Sagittarius solstice are names that indicate in which constellations the two solstices are currently located. These terms are not widely used, though, and until December 1989 the first solstice was in Gemini, according to official IAU boundaries.

- The Latin names Hibernal solstice (winter), and Aestival solstice (summer) are sometimes used.

Solstice terms in East Asia

The traditional East Asian calendars divide a year into 24 solar terms (節氣). Xiàzhì (pīnyīn) or Geshi (rōmaji) (Chinese and Japanese: 夏至; Korean: 하지(Haji); Vietnamese: Hạ chí; literally: "summer's extreme") is the 10th solar term, and marks the summer solstice. It begins when the Sun reaches the celestial longitude of 90° (around June 21) and ends when the Sun reaches the longitude of 105° (around July 7). Xiàzhì more often refers in particular to the day when the Sun is exactly at the celestial longitude of 90°.

Dōngzhì (pīnyīn) or Tōji (rōmaji) (Chinese and Japanese: 冬至; Korean: 동지(Dongji); Vietnamese: Đông chí; literally: "winter's extreme") is the 22nd solar term, and marks the winter solstice. It begins when the Sun reaches the celestial longitude of 270° (around December 22 ) and ends when the Sun reaches the longitude of 285° (around January 5). Dōngzhì more often refers in particular to the day when the Sun is exactly at the celestial longitude of 270°.

The solstices (as well as the equinoxes) mark the middle of the seasons in East Asian calendars. Here, the Chinese character 至 means "extreme", so the terms for the solstices directly signify the summits of summer and winter, a linkage that may not be immediately obvious in Western languages.

Heliocentric view of the seasons

The cause of the seasons is that the Earth's axis of rotation is not perpendicular to its orbital plane (the flat plane made through the center of mass (barycenter) of the solar system (near or within the Sun) and the successive locations of Earth during the year), but currently makes an angle of about 23.44° (called the "obliquity of the ecliptic"), and that the axis keeps its orientation with respect to inertial space. As a consequence, for half the year (from around 20 March to 22 September) the northern hemisphere tips to the Sun, with the maximum around 21 June, while for the other half year the southern hemisphere has this distinction, with the maximum around 21 December. The two moments when the inclination of Earth's rotational axis has maximum effect are the solstices.

The table at the top of the article gives the instances of equinoxes and solstices over several years. Refer to the equinox article for some remarks.

At the northern solstice the subsolar point reaches to 23.44° north, known as the tropic of Cancer. Likewise at the southern solstice the same thing happens for latitude 23.44° south, known as the tropic of Capricorn. The subsolar point will cross every latitude between these two extremes exactly twice per year.

Also during the northern solstice places situated at latitude 66.56° north, known as the Arctic Circle will see the Sun just on the horizon during midnight, and all places north of it will see the Sun above horizon for 24 hours. That is the midnight sun or midsummer-night sun or polar day. On the other hand, places at latitude 66.56° south, known as the Antarctic Circle will see the Sun just on the horizon during midday, and all places south of it will not see the Sun above horizon at any time of the day. That is the polar night. During the southern solstice the effects on both hemispheres are just the opposite.

At the temperate latitudes, during summer the Sun remains longer and higher above the horizon, while in winter it remains shorter and lower. This is the cause of summer heat and winter cold.

- Further information: effect of sun angle on climate

The seasons are not caused by the varying distance of Earth from the Sun due to the orbital eccentricity of the Earth's orbit. This variation does make such a contribution, but is small compared with the effects of exposure because of Earth's tilt. Currently the Earth reaches perihelion at the beginning of January, which is during the northern winter and the southern summer. The Sun, being closer to Earth and therefore hotter, does not cause the whole planet to enter summer. Although it is true that the northern winter is somewhat warmer than the southern winter, the placement of the continents, ice-covered Antarctica in particular, may also play an important factor. In the same way, during aphelion at the beginning of July, the Sun is farther away, but that still leaves the northern summer and southern winter as they are with only minor effects.

Due to Milankovitch cycles, the Earth's axial tilt and orbital eccentricity will change over thousands of years. Thus in 10,000 years one would find that Earth's northern winter occurs at aphelion and its northern summer at perihelion. The severity of seasonal change — the average temperature difference between summer and winter in location — will also change over time because the Earth's axial tilt fluctuates between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees.

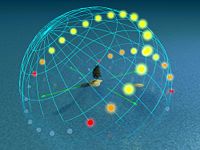

Geocentric view of the seasons

The explanation given in the previous section is useful for observers in outer space. They would see how the Earth revolves around the Sun and how the distribution of sunlight on the planet would change over the year. To observers on Earth, it is also useful to see how the Sun seems to revolve around them. These pictures show such a perspective as follows. They show the day arcs of the Sun, the paths the Sun tracks along the celestial dome in its diurnal movement. The pictures show this for every hour on both solstice days. The longer arc is always the summer track and the shorter one the winter track. The two tracks are at a distance of 46.88° (2 × 23.44°) away from each other.

In addition, some 'ghost' suns are indicated below the horizon, as much as 18° down. The Sun in this area causes twilight. The pictures can be used for both the northern and southern hemispheres. The observer is supposed to sit near the tree on the island in the middle of the ocean. The green arrows give the cardinal directions.

- On the northern hemisphere the north is to the left, the Sun rises in the east (far arrow), culminates in the south (to the right) while moving to the right and sets in the west (near arrow). Both rise and set positions are displaced towards the north in summer, and towards the south for the winter track.

- On the southern hemisphere the south is to the left, the Sun rises in the east (near arrow), culminates in the north (to the right) while moving to the left and sets in the west (far arrow). Both rise and set positions are displaced towards the south in summer, and towards the north for the winter track.

The following special cases are depicted.

- On the equator the Sun is not overhead every day, as some people think. In fact that happens only on two days of the year, the equinoxes. The solstices are the dates that the Sun stays farthest away from the zenith, only reaching an altitude of 66.56° either to the north or the south. The only thing special about the equator is that all days of the year, solstices included, have roughly the same length of about 12 hours, so that it makes no sense to talk about summer and winter. Instead, tropical areas often have wet and dry seasons.

- The day arcs at 20° latitude. The Sun culminates at 46.56° altitude in winter and 93.44° altitude in summer. In this case an angle larger than 90° means that the culmination takes place at an altitude of 86.56° in the opposite cardinal direction. For example in the southern hemisphere, the Sun remains in the north during winter, but can reach over the zenith to the south in midsummer. Summer days are longer than winter days, but the difference is no more than two or three hours. The daily path of the Sun is steep at the horizon the whole year round, resulting in a twilight of only about one hour.

- The day arcs at 50° latitude. The winter Sun does not rise more than 16.56° above the horizon at midday, and 63.44° in summer above the same horizon direction. The difference in the length of the day between summer and winter is striking. Likewise is the difference in direction of sunrise and sunset. Also note the different steepness of the daily path of the Sun above the horizon in summer and winter. It is much shallower in winter. Therefore not only is the Sun not reaching as high, it also seems not to be in a hurry to do so. But conversely this means that in summer the Sun is not in a hurry to dip deeply below the horizon at night. At this latitude at midnight the summer sun is only 16.56° below the horizon, which means that astronomical twilight continues the whole night. This phenomenon is known as the grey nights, nights when it does not get dark enough for astronomers to do their observations. Above 60° latitude the Sun would be even closer to the horizon, only 6.56° away from it. Then civil twilight continues the whole night. This phenomenon is known as the white nights. And above 66° latitude, of course, one would get the midnight sun.

- The day arcs at 70° latitude. At local noon the winter Sun culminates at −3.44°, and the summer Sun at 43.44°. Said another way, during the winter the Sun does not rise above the horizon, it is the polar night. There will be still a strong twilight though. At local midnight the summer Sun culminates at 3.44°, said another way, it does not set, it is the polar day.

- The day arcs at the pole. All the time the Sun is 23.44° above or below the horizon, depending on whether it is the summer or winter solstice. In the latter case, that is enough to not even have any twilight. All directions are north at the South Pole and south at the North pole. There is also no south at the South Pole, no north at the North Pole, and neither east nor west is discernible at either pole.

Due to atmospheric refraction, the Sun may already appear above the horizon when the real, geometric Sun is still below it.

Cultural aspects

Many cultures celebrate various combinations of the winter and summer solstices, the equinoxes, and the midpoints between them, leading to various holidays arising around these events. For the December solstice, Christmas is the most popular holiday to have arisen. In addition, Yalda, Saturnalia, Karachun, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and Yule (see winter solstice for more) are also celebrated around this time. For the June solstice, Catholic and Nordic Protestant cultures celebrate the feast of St. John from June 23 to June 24 (see St. John's Eve, Ivan Kupala Day, Midsummer), while Neopagans observe Midsummer. For the vernal (spring) equinox, several spring-time festivals are celebrated, such as the observance in Judaism of Passover. The autumnal equinox has also given rise to various holidays, such as the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. At the midpoints between these four solar events, cross-quarter days are celebrated.

In many cultures the solstices and equinoxes traditionally determine the midpoint of the seasons, which can be seen in the celebrations called midsummer and midwinter. Along this vein, the Japanese celebrate the start of each season with an occurrence known as Setsubun. The cumulative cooling and warming that result from the tilt of the planet become most pronounced after the solstices.

In the Hindu calendar, two sidereal solstices are named Uttarayana and Dakshinayana. The former occurs around January 14 each year, while the latter occurs around July 14 each year. These mark the movement of the Sun along a sidereally fixed zodiac (precession is ignored) into Mesha, a zodiacal sign which corresponded with Aries about 285, and into Tula, the opposite zodiacal sign which corresponded with Libra about 285.

See also

References

- ↑ United States Naval Observatory (01/28/07). "Earth's Seasons: Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion, 2000-2020".

- ↑ "solstice" (html). The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition (2000). Retrieved on 2008-10-23.

- ↑ The Principle of relativity was first applied to inertial frames of reference by Albert Einstein. Before then the concepts of absolute time and space applied by Isaac Newton prevailed. The motion of the sun across the sky is still called "apparent motion" in celestial navigation in deference the the Newtonian view, but the reality of the supposed "real motion" has no special laws to commend it, both are visually verifiable and both follow the same laws of physics.

- ↑ For an introduction to these topics of astronomy refer to Bowditch, Nathaniel (1995 Edition) (pdf). The American Practical Navigator: an Epitome of Navigation. Bethesda, Maryland: National Imagery and Mapping Agency. Chapter 15 Navigational Astronomy. http://www.irbs.com/bowditch/pdf/chapt15.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

- ↑ Strabo. The Geography. pp. II.5.1. "sphairikē ... tēs gēs epiphaneia, spherical is the surface of the Earth".

- ↑ Strabo. The Geography. pp. II.5.2. "sphairoeidēs ... ouranos, spherical in appearance ... is heaven".

- ↑ Strabo II.5.2., "aplaneis asteres kata parallēlōn pherontai kuklōn", "the fixed stars are borne in parallel circles"

- ↑ Strabo II.5.2, "ho di'autēs (gē) aksōn kai tou ouranou mesou tetagmenos", "the axis through it (the Earth) extending through the middle of the sky"

- ↑ Cleomedes; Alan C. Bowen; Robert B. Todd (Translators) (2004). Cleomedes' Lectures on Astronomy: A Translation of The Heavens. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 41. ISBN 0520233255, ISBN 9780520233256. This translation cites this passage at the end of Book I Chapter 2 but other arrangements have it at the start of Chapter 3. In the Greek version of Cleomedes; Hermann Ziegler (Editor) (1891). Cleomedis De motu circulari corporum caelestium libri duo. B. G. Teubneri. pp. 32. the passage starts Chapter 4.

External links

Calculations, plots and tables

- "Earth's Seasons, Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion, 2000–2020". United States Naval Observatory, Astronomical Applications Department.

- Weisstein, Eric (1996-2007). "Summer Solstice". Eric Weisstein's World of Astronomy. Retrieved on 2008-10-24. "The above plots show how the date of the summer solstice shifts through the Gregorian calendar according to the insetion of leap years."

- Solstice Dates and Times

- Solstice, Equinox & Cross-Quarter Moments for 2006 and other years, for several timezones

- Calculation of Length of Day (Formulas and Graphs)

- Calculate the Time of Solstices in Excel, CAD or your other programs. The Sun API is freeware and claimed accurate. For Microsoft® Windows® Operating Systems (presumably 32-bit only) (Note DLL may run under Wine (software)).

Debate about season start

- The seasons begin at the time of the solstice or equinox (from the Bad Astronomer)

- Solstice does not signal season's start? (from the Bad Astronomer)

Pictures and videos

|

|||

|

||