Social Democratic and Labour Party

| Social Democratic and Labour Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Mark Durkan MP, MLA |

| Founded | 1970 |

| Headquarters | 121 Ormeau Road Belfast, BT7 1SH Northern Ireland |

| Political Ideology | Social democracy, Irish nationalism |

| Political Position | Centre-left |

| International Affiliation | Socialist International |

| European Affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| European Parliament Group | n/a |

| Colours | Green, red |

| Website | http://www.sdlp.ie |

| See also | Politics of the UK Political parties |

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP; Irish: Páirtí Sóisialta Daonlathach an Lucht Oibre) is one of the two major nationalist parties in Northern Ireland. During the Troubles, the SDLP was consistently the most popular nationalist party in Northern Ireland, but since the IRA cease-fire, it has been gaining fewer votes than the main republican rival, Sinn Féin.

During the troubles, the party was distinct from Sinn Féin above all in the SDLP rejection of violence to achieve Irish nationalist goals, while Sinn Féin supported IRA methods.

The SDLP is also a social democratic party, and is affiliated to the Socialist International. The party's youth group is SDLP Youth. Through the SDLP's membership of the Party of European Socialists, they are sister parties with social democratic parties throughout Europe, including the Irish Labour Party and British Labour Party, and it is understood the parties have an unspoken electoral agreement.

The party currently has three MPs in the British House of Commons, where they take the Labour whip, and 16 MLAs in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Unlike other Northern Ireland MPs, SDLP Members of Parliament sit with the Labour Party MPs on the government benches in the House of Commons.

Contents |

Leaders

- Gerry Fitt (1970–79)

- John Hume (1979–2001)

- Mark Durkan (2001–present)

Foundation

The party was founded in 1970, when six Stormont MPs and one Senator, former members of the Republican Labour Party (a fragment of the Irish Labour Party), the National Democrats (a small social democratic nationalist party), individual nationalists and members of the Northern Ireland Labour Party, joined to form a new party. The SDLP initially rejected the Nationalist Party's policy of abstentionism and sought to fight for civil rights within the Stormont system. The SDLP, though, quickly came to the view that Stormont was unreformable and withdrew from the Parliament of Northern Ireland. Within three years, the party was in government in Northern Ireland. Taking 19 of 75 seats in the Northern Ireland Assembly, the SDLP became the minority party in a power-sharing executive with Brian Faulkner's Unionists on 1 January 1974. The Assembly and Executive were short-lived, however, collapsing after only four months, and it was 25 years before the party sat on an executive again.

|

Irish Political History series |

|---|

Nationalism

|

|

Main articles

Parties & Organisations

Documents & Ideas

Songs

Cultural

Other movements

|

Aims

There is a debate over the intentions of the party's founders, with some now claiming that the aim was to provide a political movement to unite constitutional nationalists who opposed the paramilitary campaign of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and wished to campaign for civil rights for Catholics and a united Ireland by peaceful, constitutional means. However, others argue that, as the name implies, the emphasis was originally on creating a social democratic party rather than a nationalist party. This debate between social democracy/socialism and nationalism was to persist for the first decade of the party's existence. Founder and first leader Gerry Fitt — a former leader of the explicitly socialist Republican Labour Party — would later claim that it was the party's decision to demand a Council of Ireland as part of the Sunningdale Agreement that signified the point at which the party adopted a clear nationalist agenda. He would later leave the party in 1980, claiming that it was no longer the party it was intended to be.

However the party itself argues that its earliest publications show they have remained consistent in their search for a way out of an impasse in Northern Ireland that satisfies nationalist desires and calms unionist fears. The SDLP were the first to advocate the so-called principle of consent — recognising that fundamental changes in Northern Ireland's constitutional status could only come with the agreement of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland, despite the unionist majority partition had guaranteed there. However, the SDLP has always been clear that this should not mean that anybody should have a veto on change or equality.

For most of its existence Sinn Féin ridiculed the principle of consent. However, they grudgingly agreed to it when signing up to the Good Friday Agreement. The principle of consent, also widely accepted by moderate unionists, was explicitly endorsed by a large majority of Irish people in referendums (held on the same day) that endorsed the agreement.

Whilst anxious to achieve devolved government in Northern Ireland (which the British Government had prorogued in 1972), the SDLP were also insistent on what was then known as the Irish dimension — in other words a defined constitutional role for the Republic in northern affairs. This issue led to Gerry Fitt's decision to leave in 1980. Mr Fitt had agreed to enter into talks with Humphrey Atkins, the Secretary of State, which excluded an Irish dimension but was then rebuffed by his party conference.

John Hume was an advocate of a joint authority approach where both the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom would exercise political power. This was a central idea of the New Ireland Forum which brought together mainstream Irish parties in the 1980s. However, this was rejected out-of-hand by Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister, in a speech that became known as "out, out, out" because she dismissed every proposal of the forum by saying "that is out".

The horrified reaction of the Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald to this speech and the electoral success of Sinn Féin following the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike shocked the Thatcher Government and they were receptive to Fitzgerald's lobbying on behalf of the SDLP which eventually led to the Anglo Irish Agreement, which was opposed by both unionists and republicans. Republicans were concerned that the agreement did not go far enough. Unionists staged a demonstration of some 200,000 people in Belfast city centre.

While the SDLP's opponents claimed the party had become "post-nationalist" (following a speech where John Hume referred to "an increasingly post-nationalist Europe") after the Good Friday Agreement, Mark Durkan has recently described the party as republican. Durkan often emphasises to unionists that the protections and constitutional mechanisms of the Good Friday Agreement would remain in the United Ireland that the SDLP seeks.

Key proposals

- United Ireland

- Devolution as long as Northern Ireland remains part of the United Kingdom

- Social democracy

Belfast Agreement

The SDLP were key players in the talks throughout the 1990s that led to the signing of the Belfast Agreement in 1998. John Hume won a Nobel Peace Prize that year with Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble in recognition of their efforts.

Power-sharing government

The SDLP served in the power-sharing Executive in Northern Ireland, alongside the Ulster Unionist Party, the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin. Both Seamus Mallon and Mark Durkan served as Deputy First Minister alongside the UUP's First Minister David Trimble.

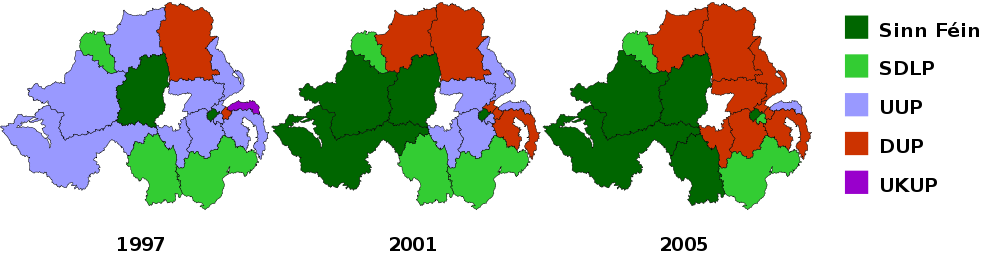

Recent electoral performance

The SDLP was the largest nationalist party in Northern Ireland from the time of its foundation until the beginning of the 21st century. In 1998, it became the biggest party overall in terms of votes received, the first (as so far, only) time this had been achieved by a nationalist party. In the 2001 General Election and in the 2003 Assembly Election, Sinn Féin won more seats and votes than the SDLP for the first time.

The retirement of John Hume was followed by a period when the party started slipping electorally. In the 2004 European elections, Hume stood down and the SDLP failed to retain the seat he had held since 1979, losing to Sinn Féin.

Some see the SDLP as first and foremost a party representing Catholic interests, with voters concentrated in rural areas and the professional classes, rather than a vehicle for Irish nationalism. The SDLP reject this argument, pointing to their strong support in Derry and their victory in South Belfast in the 2005 election. Furthermore, in the lead up to the 2005 Westminster Election, they published a document outlining their plans for a politically united Ireland. Their decline in Northern Ireland outside of two particular strongholds, has led some to dub the party the "South Down and Londonderry Party"[1]

The party claims that the 2005 Westminster elections — when they lost Newry and Armagh to Sinn Féin but Durkan comfortably held Hume's seat of Foyle whilst the SDLP also gained South Belfast with a slightly bigger share of the vote than in the 2003 assembly elections — shows that the decline caused by Sinn Féin's rejection of physical force republicanism has slowed and that their vote share demands they play a central role in any constitutional discussions. Signs are that the Irish government are receptive to this view, though the British Government remain focused on Sinn Féin and the Democratic Unionist Party, as the mechanisms of government outlined in the Agreement mean that it is only necessary that a majority of assembly members from each community (which these two parties currently have) agree a way forward.

In July 2005, the IRA announced an end to their campaign of armed resistance to British rule. The SDLP fear that the British Government will then withdraw pressure on the republicans to end their rôle in "criminality" — the illegal activities taken to fund the "struggle" but which, in the eyes of many critics, have now taken on a life of their own as a source of funds for the republican movement's infrastructure.

The SDLP endorsed and actively supported the replacement of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (a force which many nationalists opposed) with the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

Possible merger

In recent years there has been a debate in the party on the prospects of amalgamation with Fianna Fáil[2], a party in the Republic of Ireland, while the possibility of merger with the Irish Labour Party or even Fine Gael have been speculated about by others. However, little has come of this speculation and no merger seems likely as of now.

Fianna Fáil has said that it plans to organise in Northern Ireland in future, although it remains to be seen what form this will take and the effect it will have.[3]

Fianna Fáil has registered with the UK Electoral Commission and is now a recognised party in Northern Ireland.

Westminster Parliament

With the collapse of the UUP in the 2005 UK general election and Sinn Féin's continual abstention from Westminster, the SDLP is once more the second largest parliamentary grouping from Northern Ireland at Westminster. The SDLP sees this as a major opportunity to become the voice of Irish Nationalism in Westminster and to provide effective opposition to the much enlarged DUP group. The SDLP is consequently paying more attention to the Westminster Parliament and working to strengthen its ties with the Parliamentary Labour Party, whose whip they informally accept. The SDLP has been a vocal opponent at Westminster of the proposal to extend detention without trial to 42 days and previously opposed measures to extend detention to 90 days and 28 days. SDLP Leader Mark Durkan recently tabled an Early Day Motion on cluster munitions which gained cross-party support and was quickly followed by a decision by the UK government to support a ban.

Proposed Dáil participation

The SDLP, along with Sinn Féin, have long sought speaking rights in Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Republic's parliament. In 2005, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern put forward a tentative proposal to allow MPs and MEPs from Northern Ireland to participate in debates on the region. However, it met with vociferous opposition from the Republic's main opposition parties, and the plan was subsequently shelved.[4] Unionists had also strongly opposed the proposal.

SDLP elected representatives

MPs

- Mark Durkan — Foyle

- Alasdair McDonnell — Belfast South

- Eddie McGrady — South Down

MLAs

- John Dallat — East Londonderry

- Tommy Gallagher — Fermanagh & South Tyrone

- Mark Durkan — Foyle

- Pat Ramsey — Foyle

- Mary Bradley — Foyle

- Patsy McGlone — Mid Ulster

- Dominic Bradley — Newry and Armagh

- Declan O'Loan — North Antrim

- Alban Maginness — Belfast North

- Thomas Burns — South Antrim

- Alasdair McDonnell — Belfast South

- Carmel Hanna — Belfast South

- Margaret Ritchie — South Down

- PJ Bradley — South Down

- Dolores Kelly — Upper Bann

- Alex Attwood — Belfast West

References and notes

See also

- Category:Social Democratic and Labour Party politicians

- Demographics and politics of Northern Ireland

- List of Social Democratic and Labour Party MPs

External links

- SDLP

- SDLP Youth

- El Blogador, Irish political discussion forum with pro-SDLP slant

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||