Great Smoky Mountains

| Great Smoky Mountains | |

|

View from atop Mount Le Conte

|

|

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| States | North Carolina, Tennessee |

| Part of | Appalachian Mountains |

| Borders on | Bald Mountains, Unicoi Mountains |

| Highest point | Clingmans Dome |

| - elevation | 6,643 ft (2,025 m) |

| - coordinates | |

| Orogeny | Alleghenian |

Appalachian Mountain system

|

|

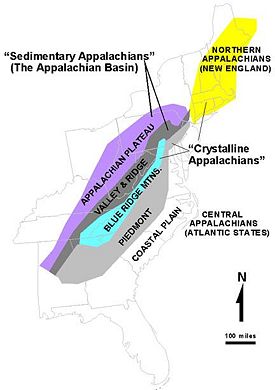

The Great Smoky Mountains are a mountain range rising along the Tennessee-North Carolina border in the southeastern United States. They are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains, and form part of the Blue Ridge Physiographic Province. The range is sometimes called the Smoky Mountains or the Smokey Mountains, and the name is commonly shortened to the Smokies. The Great Smokies are best known as the home of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which protects most of the range. The park was established in 1934, and with over 9 million visits per year, it is the most-visited national park in the United States.[1]

The Great Smokies are part of an International Biosphere Reserve. The range is home to approximately 38,000 acres (150 km2) of old growth forest, constituting the largest such stand east of the Mississippi River.[2] The cove hardwood forests in the range's lower elevations are among the most diverse ecosystems in North America, and a 13,000-acre (53 km2) boreal forest— one of only ten such stands in Southern Appalachia— coats the range's upper elevations.[3] The Great Smokies are also home to the densest black bear population in the Eastern United States and the most diverse salamander population outside of the tropics.[4]

Along with the Biosphere reserve, the Great Smokies have been designated a World Heritage Site. The U.S. National Park Service preserves and maintains 78 structures within the national park that were once part of the numerous small Appalachian communities scattered throughout the range's river valleys and coves. There are four National Historic Districts within the national park and ten individual structures within the park are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The name "Smoky" comes from the natural fog that often hangs over the range and presents as large smoke plumes from a distance. This fog, which is most common in the morning and after rainfall, is the result of warm humid air from the Gulf of Mexico cooling rapidly in the higher elevations of Southern Appalachia.[5]

Contents |

Geography

The Great Smoky Mountains stretch from the Pigeon River in the northeast to the Little Tennessee River to the southwest. The northwestern half of the range gives way to a series of elongate ridges known as the "Foothills," the outermost of which include Chilhowee Mountain and English Mountain. The range is roughly bounded on the south by the Tuckasegee River and to the southeast by Soco Creek and Jonathan Creek. The Great Smokies comprise parts of Blount County, Sevier County, and Cocke County in Tennessee and Swain County and Haywood County in North Carolina.

The sources of several rivers are located in the Smokies, including the Little Pigeon River, the Oconaluftee River, and Little River. Streams in the Smokies are part of the Tennessee River watershed and are thus entirely west of the Eastern Continental Divide. The largest stream wholly within the park is Abrams Creek, which rises in Cades Cove and empties into the Chilhowee Lake impoundment of the Little Tennessee River near Chilhowee Dam. Other major streams include Hazel Creek and Eagle Creek in the southwest, Raven Fork near Oconaluftee, Cosby Creek near Cosby, and Roaring Fork near Gatlinburg. The Little Tennessee River passes through four impoundments along the range's southwestern boundary, namely Tellico Lake, Chilhowee Lake, Calderwood Lake, and Fontana Lake.

Notable peaks

The highest point in the Smokies is Clingmans Dome, which rises to an elevation of 6,643 feet (2,025 m). The mountain is the highest in Tennessee and the third highest in the Appalachian range. Clingmans Dome also has the range's highest topographical prominence at 4,503 feet (1,373 m). Mount Le Conte is the tallest (i.e., from immediate base to summit) mountain in the range, rising 5,301 feet (1,616 m) from its base in Gatlinburg to its 6,593-foot (2,010 m) summit.

| Mountain | Elevation | Prominence | General location | Trail access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clingmans Dome | 6,643 ft/2,025 m | 4,503 ft/1,373 m | Central Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Mount Guyot | 6,621 ft/ 2,018m | 1,581 ft/482 m | Eastern Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Mount Le Conte | 6,593 ft/2,010 m | 1,360 ft/415 m | Central Smokies | Boulevard Trail |

| Mount Chapman | 6,417 ft/1,956 m | 577 ft/176 m | Eastern Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Old Black | 6,370 ft/1,942 m | 170 ft/52 m | Eastern Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Luftee Knob | 6,234 ft/1,900 m | 314 ft/96 m | Eastern Smokies | Balsam Mountain Trail |

| Mount Kephart | 6,217 ft/1,895 m | 657 ft/200 m | Central Smokies | Appalachian Trail/Jumpoff Trail |

| Mount Collins | 6,188 ft/1,886 m | 465 ft/142 m | Central Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Marks Knob | 6,169 ft/1,880 m | appx. 249 ft/76 m | Eastern Smokies | Balsam Mountain Trail |

| Tricorner Knob | 6,120 ft/1,865 m | 160 ft/48 m | Eastern Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Andrews Bald | 5,920 ft/1,804 m | 160 ft/48 m | Central Smokies | Forney Ridge Trail |

| Mount Sterling | 5,842 ft/1,781 m | 663 ft/202 m | Eastern Smokies | Mount Sterling Trail |

| Silers Bald | 5,607 ft/1,709 m | 337 ft/102 m | Western Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Thunderhead Mountain | 5,527 ft/1,684 m | 1087 ft/332 m | Western Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Gregory Bald | 4,949 ft/1,508 m | 1,107 ft/337 m | Western Smokies | Gregory Bald Trail |

| Mount Cammerer | 4,928 ft/1,502 m | 8 ft/2 m | Eastern Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

| Chimney Tops | 4,800 ft/1,463 m | appx. 200 ft/61 m | Central Smokies | Chimney Tops Trail |

| Blanket Mountain | 4,607 ft/1,404 m | appx. 500 ft/152 m | Western Smokies | Jakes Creek Trail |

| Shuckstack | 4,020 ft/1,225 m | 300 ft/91 m | Western Smokies | Appalachian Trail |

Climate

The Smokies rise prominently above the surrounding low terrain. For example, Mount Le Conte (6,593 feet or 2,010 m) rises more than a mile (1.6 km) above its base. Because of their prominence, the Smokies receive heavy annual amounts of precipitation. Annual precipitation amounts range from 50 to 80 inches (130–200 cm)[6], and snowfall in the winter can be heavy, especially on the higher slopes. For comparison, the surrounding terrain has annual precipitation of around 40 to 50 inches (100-130 cm).

Flooding often occurs after heavy rain. In 2004, the remnants of Hurricane Frances caused major flooding, landslides, and high winds, which was soon followed by Hurricane Ivan, making the situation worse. Other post-hurricanes, including Hurricane Hugo in 1989, have caused similar damage in the Smokies.

Geology

Most of the rocks in the Great Smoky Mountains consist of Class II Late Precambrian rocks that are part of a formation known as the Ocoee Supergroup. The Ocoee Supergroup consists primarily of slightly metamorphosed sandstones, phyllites, schists, and slate. Class I Precambrian rocks, which include the oldest rocks in the Smokies, comprise the dominant rock type in the Raven Fork Valley (near Oconaluftee) and upper Tuckasegee River between Cherokee and Bryson City. They consist primarily of metamorphic gneiss, granite, and schist. Class III Cambrian sedimentary rocks are found among the outer reaches of the Foothills to the northwest and in limestone coves such as Cades Cove.[7]

The Precambrian gneiss and schists— the oldest rocks in the Smokies— formed over a billion years ago from the accumulation of marine sediments and igneous rock in a primordial ocean. In the Late Precambrian period, this ocean expanded, and the more recent Ocoee Supergroup rocks formed from accumulations of the eroding land mass onto the ocean's continental shelf. By the end of the Paleozoic period, the ancient ocean had deposited a thick layer of marine sediments which left behind sedimentary rocks such as limestone. During the Ordovician period, the North American and African plates collided, destroying the ancient ocean and initiating the Alleghenian orogeny— the mountain-building epoch that created the Appalachian range. The Mesozoic period saw the rapid erosion of the softer sedimentary rocks from the new mountains, re-exposing the older Ocoee Supergroup formations.[8]

Around 20,000 years ago, subarctic glaciers advanced southward across North America, and although they never reached the Smokies, the advancing glaciers led to colder mean annual temperatures and an increase in precipitation throughout the range. Trees were unable to survive at the higher elevations, and were replaced by tundra vegetation. Spruce-fir forests occupied the valleys and slopes below approximately 4,950 feet (1,510 m). The persistent freezing and thawing during this period created the large blockfields that are often found at the base of large mountain slopes. Between 16,500 and 12,500 years ago, the glaciers to the north retreated and mean annual temperatures rose. The tundra vegetation disappeared, and the spruce-fir forests retreated to the highest elevations. Hardwood trees moved into the region from the coastal plains, replacing the spruce-fir forests in the lower elevations. The temperatures continued warming until around 6,000 years ago, when they began to gradually grow cooler.[9]

Flora

Heavy logging in the late 19th-century and early 20th-century devastated much of the forests of the Smokies, although 38,000 acres (150 km2) of old growth forest remains, comprising the largest old growth stand in the Eastern United States. Most of the forest is a mature second-growth hardwood forest. The range's 1,600 species of flowering plants include over 100 species of native trees and 100 species of native shrubs. The Great Smokies are also home to over 450 species of non-vascular plants, and 2,000 species of fungi.[10][11]

The forests of the Smokies are typically divided into three zones— the cove hardwood forests in the stream valleys, coves, and lower mountain slopes, the northern hardwood forests on the higher mountain slopes, and the spruce-fir or boreal forest at the very highest elevations. Balds— patches of land where trees are unexpectedly absent or sparse— are interspersed through the mid-to-upper elevations in the range. Balds include grassy balds, which are highland meadows covered primarily by thick grasses, and heath balds, which are dense thickets of rhododendron and mountain laurel typically occurring on narrow ridges. Mixed oak-pine forests are found on dry ridges, especially on the south-facing North Carolina side of the range.[12] Stands dominated by the Eastern Hemlock are occasionally found along streams and broad slopes above 3,500 feet (1,100 m).[13]

The cove hardwood forest

Cove hardwood forests, which are native to Southern Appalachia, are among the most diverse forest types in North America. The cove hardwood forests of the Smokies are mostly second-growth, although a notable 138-acre (0.56 km2) old growth patch known as Albright Grove still stands along the Maddron Bald Trail (between Gatlinburg and Cosby). Albright Grove contains some of the oldest and tallest trees in the entire range.[14]

Over 130 species of trees are found among the canopies of the cove hardwood forests in the Smokies. The dominant species include yellow birch, basswood, buckeye, tuliptree (commonly called "tulip poplar"), silverbell, sugar maple, magnolia, hickory, and hemlock.[15] The American chestnut, which was arguably the most beloved tree of the range's pre-park inhabitants, was killed off by a blight in the 1920s.

The understories of the cove hardwood forest contain thousands of species of shrubs and vines. Dominant species in the Smokies include the redbud, dogwood, rhododendron, mountain laurel, and hydrangea.[16]

The northern hardwood forest

The mean annual temperatures in the higher elevations in the Smokies are cool enough to support forest types more commonly found in the northern United States. The northern hardwood forests of the Smokies constitute the highest broad-leaved forest in the eastern United States.[17]

In the Smokies, the northern hardwood canopies are dominated by yellow birch and beech. White basswood, mountain and striped maple, and buckeye are also present. The northern hardwood understory is home to diverse species such as coneflower, skunk goldenrod, Rugels ragwort, bloodroot, hydrangea, and several species of grasses and ferns.[18]

One unique community in the northern hardwoods of the Smokies is the beech gap, or beech orchard. Beech gaps consist of high mountain gaps that have been monopolized by beech trees. The beech trees are often twisted and contorted by the high winds that occur in these gaps. Why other tree types such as the red spruce fail to encroach into the beech gaps is unknown.[19]

The spruce-fir forest

The spruce-fir forest— also called the "boreal" or "Canadian" forest— is a relic of the Ice Ages, when mean annual temperatures in the Smokies were too cold to support a hardwood forest. While the rise in temperatures between 12,500 and 6,000 years ago allowed the hardwoods to return, the spruce-fir forest has managed to survive on the harsh mountain tops, typically above 5,500 feet (1,700 m).

The spruce-fir forest consists primarily of two conifer species— red spruce and Fraser Fir. The Fraser Firs, which are native to Southern Appalachia, once dominated elevations above 6,200 feet (1,900 m) in the Great Smokies. Most of these firs were killed, however, by an infestation of the balsam wooly adelgid, which arrived in the Smokies in the early 1960s. Thus, red spruce is now the dominant species in the range's spruce-fir forest. Large stands of dead Fraser Firs remain atop Clingmans Dome and on the northwestern slopes of Old Black. While much of the red spruce stands in the Smokies were logged during World War I, the tree is still common throughout the range above 5,500 feet (1,700 m). Some of the red spruce trees in the Smokies are believed to be 300 years old, and the tallest rise to over 100 feet (30 m).[20]

The main difference between the spruce-fir forests of Southern Appalachia and the spruce-fir forests in northern latitudes is the dense broad-leaved understory of the former. The spruce-fir understories of the Smokies are home to catawba rhododendron, mountain ash, pin cherry, thornless blackberry, and hobblebush. The herbaceous and litter layers of the spruce-fir forests are pooly-lit year-round, and are thus dominated by shade-tolerant plants such as ferns, namely mountain woodfern and northern lady fern, and over 280 species of mosses.[21]

Wildflowers

- See also: Wildflowers of the Great Smoky Mountains

Many wildflowers grow in mountains and valleys of the Great Smokies, including bee balm, Solomon's seal, Dutchman's breeches, various trilliums, the Dragon's Advocate and even hardy orchids. There are two native species of rhododendron in the area. The Catawba rhododendron has purple flowers in May and June, while the rosebay rhododendron has longer leaves and blooms white or a light pink in June and July. The orange- to sometimes red-flowered and deciduous flame azalea closely follows along with the Catawbas. The closely-related mountain laurel blooms in between the two, and all of the blooms progress from lower to higher elevations. The reverse is true in autumn, when nearly-bare mountaintops covered in rime ice (frozen fog) can be separated from green valleys by very bright and varied leaf colors. The rhododendrons are broadleafs, whose leaves droop in order to shed wet and heavy snows that come through the region in winter.

Fauna

The Great Smoky Mountains are home to 66 species of mammals, over 240 species of birds, 43 species of amphibians, 60 species of fish, and 40 species of reptiles. The range has the densest black bear population east of the Mississippi River. The black bear has come to symbolize wildlife in the Smokies, and the animal frequently appears on the covers of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park's literature. Most of the range's adult eastern black bears weigh between 100 pounds (45 kg) and 300 pounds (140 kg), although some grow to more than 500 pounds (230 kg).[22]

Other mammals in the Great Smokies include the white-tailed deer, the population of which drastically expanded with the creation of the national park. The bobcat is the range's only remaining wild cat species, although sightings of mountain lions— which once thrived in the area— are still occasionally reported.[23] The coyote is not believed to be native to the range, but has moved into the area in recent years and is treated as a native species. Two species of fox— the red fox and the gray fox— are found in the Smokies, with red foxes being documented at all elevations.[24] Boars, a non-native species introduced in the early 1900s, thrive in Southern Appalachia but are considered a nuisance due to their tendency to root up and destroy plants.[25] The Smokies are home to over two dozen species of rodents, including the endangered northern flying squirrel, and 10 species of bats, including the endangered Indiana bat.[26] The National Park Service has successfully reintroduced river otters and elk into the Great Smokies. An attempt to reintroduce the red wolf in the early 1990s ultimately failed.[27]

The Smokies are home to a diverse bird population due to the presence of multiple forest types. Species that thrive in southern hardwood forests, such as the Red-eyed vireo, Wood Thrush, Wild turkey, Parula warbler, Ruby-throated hummingbird, and Tufted titmouse, are found throughout the range's lower elevations and cove hardwood forests. Species more typical of cooler climates, such as the Raven, Winter wren, Black-capped chickadee, Yellow-bellied sapsucker, Slate-colored Junco, and Blackburnian, Chestnut-sided, and Canada warblers, are found in the range's spruce-fir and northern hardwood zones.[28] Ovenbirds, Whip-poor-wills, and Downy woodpeckers live in the drier pine-oak forests and heath balds.[29] Bald eagles and Golden eagles have been spotted at all elevations in the park.[30] Peregrine falcon sightings are also not uncommon, and a Peregrine falcon eyrie is known to have existed near Alum Cave Bluffs throughout the 1930s.[31] Red-tailed hawks, the most common hawk species, have been sighted at all elevations in the range. Owl species residing in the Smokies include the Barred owl, Screech owl, and Saw-whet owl.[32]

Timber rattlesnakes— one of two poisonous snake species in the Smokies— are found at all elevations in the range. The other poisonous snake, the copperhead, is typically found at lower elevations. Other reptiles include the eastern box turtle, the fence lizard, the black rat snake, and the northern water snake.[33]

The Great Smokies are home to one of the world's most diverse salamander populations. Five of the world's nine families of salamanders are found in the range, consisting of up to thirty-one species.[34] A type of Jordan's salamander known as the redcheek salamander is found only in the Smokies.[35] The Imitator salamander is found only in the Smokies and the nearby Plott Balsams and Great Balsam Mountains.[36] Two other species— the Southern gray-cheeked salamander and the Southern Appalachian salamander— occur only in the general region.[37] Other species include the shovelnose, Blackbelly Salamander, Eastern Red-spotted Newt, and Spotted Dusky salamander.[38] The legendary hellbender inhabits the range's swifter streams.[39] Other amphibians include the American toad and the American bullfrog, wood frog, Upland chorus frog, Northern green frog, and spring peeper.[40]

Fish inhabiting the steams of the Smokies include trout, lamprey, darter, shiner, bass, and sucker. The brook trout is the only trout species native to the range, although rainbow trout were introduced in the first half of the 20th-century. Protected fish species in the range include the smoky and yellowfin madtom, the spotfin chub, and the duskytail darter.[41]

Ecosystem threats

Air pollution may be contributing to increased Red Spruce tree mortality at higher elevations and oak decline at lower elevations, while invasive hemlock woolly adelgids attack Hemlocks and balsam woolly adelgids attack Fraser Firs. Pseudoscymnus tsugae, a type of beetle in the ladybug family, Coccinellidae, has been introduced in an attempt to control the pests.[42].

Visibility now is dramatically reduced by smog from both the Southeastern United States and the Midwest, and smog forecasts are prepared daily by the Environmental Protection Agency for both nearby Knoxville, Tennessee and Asheville, North Carolina.

Culture and tourism

The culture of the area is that of Southern Appalachia, and previously the Cherokee people. Tourism is key to the area's economy, particularly in cities like Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg in Tennessee, and Cherokee, North Carolina.

Rafting, either leisurely river tubing or in full whitewater, is common all summer. Downhill skiing is also done in winter, though for a short season, at places like Cataloochee and Ober Gatlinburg.

Country music singer Dolly Parton was born and raised on a small farm in the Smokies along with her 11 other siblings (one of whom passed away in infancy). She writes many songs concerning her Tennessee upbringing, and starred in the 1986 film, A Smoky Mountain Christmas.

References

- ↑ National Park Service

- ↑ Rose Houk, Great Smoky Mountains National Park: A Natural History Guide (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993), 198.

- ↑ Houk, 50.

- ↑ Houk, 112, 119.

- ↑ Houk, 19.

- ↑ Southern Appalachian Precipitation Study

- ↑ Harry Moore, A Roadside Guide to the Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 32.

- ↑ Houk, 10-17.

- ↑ Moore, 40-44.

- ↑ Great Smoky Mountains - Nature & Science

- ↑ Houk, 41.

- ↑ Houk, 21-23.

- ↑ C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr., The Amphibians of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 46-47.

- ↑ Marti Davis, "Serene virgin forest gives respite from July heat." Knoxnews.com, 9 July 2006. Retrieved: 19 May 2008.

- ↑ Houk, 24-25.

- ↑ Houk, 25-26.

- ↑ Houk, 28.

- ↑ 28-29.

- ↑ Houk, 30.

- ↑ Houk, 50-53.

- ↑ Houk, 50, 54-55.

- ↑ Donald Linzey, Mammals of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Blackburg, Va.: McDonald & Woodward Publishing Co., 1995), 1.

- ↑ Linzey, 88-89.

- ↑ Linzey, 65-66.

- ↑ Linzey, 93-94.

- ↑ Linzey, 1, 21, 40.

- ↑ Great Smoky Mountains National Park — Mammals. 24 July 2006. Retrieved: 3 November 2008.

- ↑ Arthur Stupka, Notes on the Birds of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1963), 12.

- ↑ Stupka, 13-14.

- ↑ Stupka, 37-40.

- ↑ Stupka, 42.

- ↑ Stupka, 12, 67-72.

- ↑ Houk, 131.

- ↑ C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr., The Amphibians of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 7, 13.

- ↑ Dodd, 185-186.

- ↑ Dodd, 123.

- ↑ Dodd, 189-194.

- ↑ Dodd, 13, 120-129, 178.

- ↑ Dodd, 26.

- ↑ Dodd, 86-87, 230-231, 243.

- ↑ Great Smoky Mountains National Park — Fish. 8 March 2007. Retrieved: 3 November 2008.

- ↑ McClure, Mark S; Carole A S - J Cheah. "Pseudoscymnus tsugae (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)". Biological Control: A Guide to Natural Enemies in North America. Cornell University. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

External links

- National Park Service website

- Official Nonprofit Partner Event Calendars

- National Weather Service Southern Appalachian Precipitation study

- Cornell University study on invasive balsam woolly adelgid control

- History and maps

- The Great Smoky Mountains Regional Project — a collection of documents and early photographs regarding the Great Smokies and surrounding communities

- Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont

- Great Smoky Mountains landforms

- Photos of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- Smoky Mountains Online Radio Show