The Brothers Karamazov

| The Brothers Karamazov | |

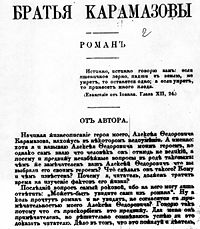

First page from The Russian Messenger. |

|

| Author | Fyodor Dostoevsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Братья Карамазовы (Brat'ya Karamazovy) |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre(s) | Philosophical novel |

| Publisher | The Russian Messenger (as Serial) |

| Publication date | November 1880 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | NA |

| Preceded by | A Gentle Creature |

| Followed by | A Writer's Diary |

The Brothers Karamazov (Russian: Братья Карамазовы; /'bratʲjə karə'mazəvɨ/) is the final novel by the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky, and is generally considered the culmination of his life's work. Dostoevsky spent nearly two years writing The Brothers Karamazov, which was published as a serial in The Russian Messenger and completed in November 1880. Dostoevsky intended it to be the first part in an epic story titled The Life of a Great Sinner,[1] but he died less than four months after its publication.

The book portrays a patricide in which each of the murdered man's sons share a varying degree of complicity. On a deeper level, it is a spiritual drama of moral struggles concerning faith, doubt, reason, free will and modern Russia. Dostoevsky composed much of the novel in Staraya Russa, which is also the main setting of the novel.

Since its publication, it has been acclaimed all over the world by thinkers as diverse as Sigmund Freud[2] and Albert Einstein[3] as one of the supreme achievements in world literature.

Context and background

Dostoevsky began his first notes for The Brothers Karamazov in April 1878. Several influences can be gleaned from the very early stages of the novel's genesis. The first involved the profound effect the Russian philosopher and thinker Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov had on Dostoevsky at this time of his life. Fyodorov advocated a Christianity in which human redemption and resurrection could occur on earth through sons redeeming the sins of their fathers to create human unity through a universal family. The tragedy of patricide in this novel becomes much more poignant as a result because it is a complete inversion of this ideology. The brothers in the story do not resurrect their father but instead are complicit in his murder, which in itself represents complete human disunity for Dostoevsky.

Though religion and philosophy profoundly influenced Dostoevsky in his life and in The Brothers Karamazov, a much more personal tragedy altered the course of this work. In May 1878 Dostoevsky's novel was interrupted by the death of his three-year-old son Alyosha. As tragic as this would be under any circumstances, Alyosha's death was especially devastating for Dostoevsky because the child died of epilepsy, a condition he inherited from his father. The novelist's grief for his young son is readily apparent throughout the book; Dostoevsky made Alyosha the name of the stated hero of the novel, as well as imbuing him with all of the qualities he himself most admired and sought after. This heartbreak also appears in the novel as the story of Captain Snegiryov and his young son Ilyusha.

A very personal experience also influenced Dostoevsky's choice for a patricide to dominate the external action of the novel. In the 1850s, while serving his katorga (forced labor) sentence in Siberia for circulating politically subversive texts, Dostoevsky encountered the young man Ilyinsky who had been convicted of killing his father to acquire an inheritance. Nearly ten years after this encounter Dostoevsky learned that Ilyinsky had been falsely convicted and later exonerated when the actual murderer confessed to the crime. The impact of this encounter on the author is readily apparent in the novel, as it serves as much of the driving force for the plot. Many of the physical and emotional characteristics of the character Dmitri Karamazov are closely paralleled to those of Ilyinsky.

Structure

Although it was written in the 19th century, The Brothers Karamazov displays a number of modern elements. Dostoevsky composed the book with a variety of literary techniques that led many of his critics to characterize his work as "slipshod". The most pertinent example that comes across to the reader is the omniscient narrator. Though he is privy to many of the thoughts and feelings of the protagonists, he is a self-proclaimed writer, and characterizes his own mannerisms so often throughout the novel that he becomes a character himself. Through his descriptions the narrator's voice merges imperceptibly into the tone of the people he is describing. Thus, there is no voice of authority in the story (see Mikhail Bakhtin "Problems of Dostoyevsky’s Art: Polyphony and Unfinalizability" for more on the relationship between Dostoevsky and his characters). This technique enhances the theme of truth, making the tale itself completely subjective.

Speech is another technique that Dostoevsky employs uniquely in this work. Every character has a unique manner of speaking which expresses much of the inner personality of each person. For example, The attorney Fetyukovich is characterized by malapropisms (e.g. 'robbed' for 'stolen', and at one point declares five possible suspects in the murder 'irresponsible' rather than innocent). Several plot digressions provide insight into other, apparently minor characters. For example, the narrative in Book Six is almost entirely devoted to the story of Zosima's biography, which in itself contains a confession from a man Zosima met many years before who seems to have nothing at all to do with the events chronicled in the main plot.

Translation

The diverse array of literary techniques and distinct voices in the novel makes the translation of special importance. The Brothers Karamazov has been translated from the original Russian into a number of languages. In English, the translation by Constance Garnett probably continues to be the most widely read. However, some have criticized Garnett for taking too much liberty with Dostoevsky's text while translating the novel in a Victorian manner. A case in point is that in Garnett's translation the lower class characters speak in Cockney English. Therefore, it would serve the reader well to sample many translations before deciding on a particular text.

In 1958, Manuel Komroff released a translation of the novel, published by The New American Library of World Literature, Inc. [4] In 1976, Ralph Matlaw made a thorough revision of Garnett's work the basis of his Norton Critical Edition volume,[5] which became the basis for Victor Terras' influential A Karamazov Companion.[6] In 1990 Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky released a new translation which won a PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Prize in 1991 and garnered positive reviews from The New York Times Book Review and Joseph Frank, who praised it for being the most faithful to Dostoevsky's original Russian.[7] The translation by Andrew R. MacAndrew is also highly regarded .

Major characters

Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov

The father, Fyodor Pavlovich, is a 55-year-old "sponger" and buffoon who had sired three sons during the course of his two marriages. He is also rumored to have fathered an illegitimate son, Pavel Smerdyakov whom he employed as his servant. Fyodor took no interest in any of his sons. As a result, they were all raised apart from each other and their father. The murder of Fyodor and the ensuing implication of his oldest son provides much of the plot in the novel.

Dmitri Fyodorovich Karamazov

Dmitri (Mitya, Mitka, Mitenka, Mitri) is 28 years old, Fyodor's eldest son and the only offspring of his first marriage. Dmitri is a sensualist much like his father, and the two men's personalities often clash. Dmitri spends large amounts of money on debauchery-filled nights with plenty of champagne, women, and whatever entertainment and stimulation money can buy, soon exhausting any source of cash he comes across. This leads to further conflict with his father, who he believes is withholding his rightful inheritance, and his lack of money will cast suspicion upon him in the murder investigation. He finally comes to the brink of murdering his father when they begin fighting over the same woman, Grushenka. He is close to Alyosha, referring to him as his "cherub".

Ivan Fyodorovich Karamazov

Variously called Vanya, Vanka, and Vanechka, Ivan is the middle son and first by Fyodor's second marriage. He is a 24-year-old fervent rationalist, disturbed especially by the apparently senseless suffering in the world. As he says to Alyosha in the chapter "Rebellion" (Bk. 5, Ch. 4), "It's not God that I don't accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return him the ticket."

From an early age, Ivan was sullen and isolated from everyone around him. He carries a hatred for his father that is not openly expressed but which leads to his own moral guilt over Fyodor's murder and contributes to his later insanity. His father told Alyosha that he feared Ivan more than Dmitri. Some of the most memorable and acclaimed passages of the novel involve Ivan, including the chapter "Rebellion," his "poem" "The Grand Inquisitor" immediately following, and his nightmare of the devil (Bk. 11, Ch. 9).

Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov

Variously referred to as Alyosha, Alyoshka, Alyoshenka, Alyoshechka, Alexeichik, Lyosha, and Lyoshenka, Alexei is the youngest of the Karamazov brothers at 20 years of age. He is proclaimed as the hero of the novel by the narrator in the opening chapter (as well as the author in his preface). At the outset of the events chronicled in the story Alyosha is a novice in the local monastery. In this way Alyosha's beliefs act as a counterbalance to his brother Ivan's atheism. He is sent out into the world by his Elder and subsequently becomes embroiled in the sordid details of his family's dysfunction. Alyosha is also involved in a secondary plotline in which he befriends a group of school boys whose fate adds a hopeful message to the conclusion of an otherwise tragic novel. Alyosha's place in the novel is usually that of a messenger or witness to the actions of his brothers and others. He is very close to Dmitri.

Pavel Smerdyakov

Smerdyakov was born from "Stinking Lizaveta", a mute woman of the street, from which his name came—"Son of the 'reeking one'". He is widely rumored to be the illegitimate son of Fyodor Karamazov. When the novel begins, Smerdyakov is Fyodor's lackey and cook. He is morose and sullen, and, like Dostoevsky himself, epileptic. As a child he would collect stray cats so he could hang and later bury them. Smerdyakov is aloof with most people but holds a special admiration for Ivan and shares his atheistic ideology. He later confesses to Ivan that he, and not Dmitri, was the murderer of Fyodor and claims to have acted with Ivan's blessing. However, Dmitri's defense attorney pointed out that in speaking with Smerdyakov, he found him to be "falsely naive" and able to tell people what they want to hear in order to subtly foist ideas on them. Smerdyakov could have been using this technique on Ivan as well.

Agrafena Alexandrovna Svetlova

Variously called Grushenka, Grusha, and Grushka, Agrafena Alexandrovna, a 22-year-old, is the local Jezebel and has an uncanny charm among men. She was jilted by a Polish officer in her youth and came under the protection of a tyrannical miser. Grushenka inspires complete admiration and lust in both Fyodor and Dmitri Karamazov. Their rivalry for her affection is one of the most damaging circumstances that leads to Dmitri's conviction for his father's murder. She seeks to torment and then deride both Dmitri and Fyodor as a wicked amusement, a way to inflict upon others the pain she has felt at the hands of her ‘former and indisputable one’. As the book progresses, she becomes almost magnanimous.

Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtseva

Called Katya, Katka, and Katenka, Katerina Ivanovna is Dmitri's fiancée, despite his very open forays with Grushenka. She became engaged to Dmitri after he bailed her father out of a debt. Katerina produces a further love triangle among the Karamazov brothers as Ivan falls in love with her, although she is characterized as exceedingly proud. Katya is arguably presented as a beacon of nobility, generosity, and magnanimity early in the book, and as a stark reminder of everyone’s guilt ‘before all and for all’ as her downfall progresses. By the end of the trial, it is evident that she is as base as any of the characters. Even in the epilogue, after she has confessed to Mitya and agreed to direct his escape, she cannot subdue her pride after Grushenka enters the hospital room.

Zossima, the elder

- See also: Saint Ambrose of Optina

Father Zossìma is an Elder and more importantly Starets in the town monastery and Alyosha's teacher. He is something of a celebrity among the townspeople as he displays certain prophetic and healing abilities. This fact inspires both admiration and jealousy amidst his fellow monks. Zossima provides a refutation to Ivan's atheistic arguments and helps to explain Alyosha’s character. Zossima’s teachings shape the way Alyosha deals with the young boys he meets in the Ilyusha storyline.

Ilyusha

Ilyusha, Ilyushechka, or simply Ilusha in some translations, is one of the local schoolboys, and the central figure of a crucial subplot in the novel. His father, Captain Snegiryov, is an impoverished officer who is insulted by Dmitri after Fyodor hires him to threaten the latter over his debts, and the Snegiryov family is brought to shame as a result. The reader is led to believe that it is partly because of this that Ilyusha falls ill, and eventually dies (his funeral is the concluding chapter of the novel), undoubtedly to illustrate the theme that even minor actions can touch heavily on the lives of others, and that we are "all responsible for one another".

Synopsis

Book One: A Nice Little Family

The opening of the novel introduces the Karamazov family and relates the story of their distant and recent past. The details of Fyodor's two marriages as well as his indifference to the upbringing of his three children is chronicled. The narrator also establishes the widely varying personalities of the three brothers and the circumstances that have led to their return to Fyodor's town. The first book concludes by describing the mysterious religious order of Elders to which Alyosha has become devoted.

Book Two: An Inappropriate Gathering

Book Two begins as the Karamazov family arrives at the local monastery so that the Elder Zosima can act as a mediator between Dmitri and his father Fyodor in their dispute over Dmitri's inheritance. Ironically, it was the atheist Ivan's idea to have the meeting take place in such a holy place in the presence of the famous Elder. Dmitri, in appropriate fashion for him, arrives late and the gathering soon degenerates and only exacerbates the feud between Dmitri and Fyodor. This book also contains a scene in which the Elder Zosima consoles a woman mourning the death of her three-year-old son. The poor woman's grief parallels Dostoevsky's own tragedy at the loss of his young son Alyosha.

Book Three: Sensualists

The third book provides more details of the love triangle that has erupted between Fyodor, his son Dmitri, and Grushenka. Dmitri's personality is explored in the conversation between him and Alyosha as Dmitri hides near his father's home to see if Grushenka will arrive. Later that evening, Dmitri bursts into his father's house and assaults him while threatening to come back and kill him in the future. This book also introduces Smerdyakov and his origins, as well as the story of his mother, Stinking Lizaveta. At the conclusion of this book, Alyosha is witness to Grushenka's bitter humiliation of Dmitri's betrothed Katerina, resulting in terrible embarrassment and scandal for this proud woman.

Book Four: Lacerations

This section introduces a side story which resurfaces in more detail later in the novel. It begins with Alyosha observing a group of schoolboys throwing rocks at one of their sickly peers named Ilyusha. When Alyosha admonishes the boys and tries to help, Ilyusha bites Alyosha's finger. It is later learned that Ilyusha's father, a former staff-captain named Snegiryov, was assaulted by Dmitri, who dragged him by the beard out of a bar. Alyosha soon learns of the further hardships present in the Snegiryov household and offers the former staff captain money as an apology for his brother and to help Snegiryov's ailing wife and children. After initially accepting the money with joy, Snegiryov throws the money back at Alyosha out of pride and runs back into his home.

Book Five: Pro and Contra

Here, the rationalist and nihilistic ideology that permeated Russia at this time is defended and espoused passionately by Ivan Karamazov while meeting his brother Alyosha at a café. In the chapter titled "Rebellion", Ivan proclaims that he rejects the world that God has created because it is built on a foundation of suffering. In perhaps the most famous chapter in the novel, "The Grand Inquisitor", Ivan narrates to Alyosha his imagined poem that describes a leader from the Spanish Inquisition and his encounter with Jesus, who has made his return to earth. Here, Jesus is rejected by a world leader who says, "Why hast thou come now to hinder us? For Thou hast come to hinder us, and Thou knowest that.. We are working not with Thee but with him [Satan]... We took from him what thou didst reject with scorn, that last gift he offered Thee, showing Thee all the kingdoms of the earth. We took from him Rome and the sword of Caesar, and proclaimed ourselves sole rulers of the earth... We shall triumph and shall be Caesars, and then we shall plan the universal happiness of man".

Book Six: The Russian Monk

The sixth book relates the life and history of the Elder Zosima as he lies near death in his cell. Zosima describes his rebellious youth and how he found his faith while in the middle of a duel, consequently deciding to become a monk. Some of Zosima's homilies and teachings are then described which preach that people must forgive others by acknowledging their own sins and guilt before others. He explains that no sin is isolated, making everyone responsible for their neighbor's sins. Zosima represents a philosophy that responds to Ivan's, which had challenged God's creation in the previous book.

Book Seven: Alyosha

The book begins immediately following the death of Zosima. It is a commonly held perception in the town, and the monastery as well, that true holy men's bodies do not succumb to putrefaction. Thus, the expectation concerning the Elder Zosima is that his deceased body will not decompose. It comes as a great shock to the entire town that Zosima's body not only decays, but begins the process almost immediately following his death. Within the first day, the smell of Zosima's body is already unbearable. For many this calls into question their previous respect and admiration for Zosima. Alyosha is particularly devastated by the sullying of Zosima's name due to nothing more than the corruption of his dead body. One of Alyosha's companions in the monastery named Rakitin uses Alyosha's vulnerability to set up a meeting between him and Grushenka. The book ends with the spiritual regeneration of Alyosha as he embraces the earth outside the monastery and cries convulsively until finally going back out into the world, as Zosima instructed, renewed.

Book Eight: Mitya

This section deals primarily with Dmitri's wild and distraught pursuit of money so he can run away with Grushenka. Dmitri owes money to his fiancée Katerina and will believe himself to be a thief if he does not find the money to pay her back before embarking on his quest for Grushenka. This mad dash for money takes Dmitri from Grushenka's benefactor to a neighboring town on a fabricated promise of a business deal. All the while Dmitri is petrified that Grushenka may go to his father Fyodor and marry him because he already has the monetary means to satisfy her. When Dmitri returns from his failed dealing in the neighboring town, he escorts Grushenka to her benefactor's home, but quickly discovers she deceived him and left early. Furious, he runs to his father's home with a brass pestle in his hand, and spies on him from the window. He takes the pestle from his pocket. Then, there is a discontinuity in the action, and Dmitri is suddenly running away off his father's property, knocking the servant Gregory in the head with the pestle.

Dmitri is next seen in a daze on the street, covered in blood, with thousands of rubles in his hand. He soon learns that Grushenka's former betrothed has returned and taken her to a lodge near where Dmitri just was. Upon learning this, Dmitri loads a cart full of food and wine and pays for a huge orgy to finally confront Grushenka in the presence of her old flame, intending all the while to kill himself at dawn. The "first and rightful lover", however, is a boorish Pole who cheats the party at a game of cards. When his deception is revealed, he flees, and Grushenka soon reveals to Dmitri that she really is in love with him. The party rages on, and just as Dmitri and Grushenka are about to consummate their love, the police enter the lodge and inform Dmitri that he is under arrest for the murder of his father.

Book Nine: The Preliminary Investigation

Book Nine introduces the details of Fyodor's murder and describes the interrogation of Dmitri as he is questioned for the crime he maintains he did not commit. The alleged motive for the crime is robbery. Dmitri was known to have been completely destitute earlier that evening, but is suddenly seen on the street with thousands of rubles shortly after his father's murder. Meanwhile, the three thousand roubles that Fyodor Karamazov had set aside for Grushenka has disappeared. Dmitri explains that the money he spent that evening came from three thousand roubles Katerina gave him to send to her sister. He spent half that at his first meeting with Grushenka--another drunken orgy--and sewed up the rest in a cloth, intending to give it back to Katerina in the name of honor, he says. The lawyers are not convinced by this. All of the evidence points against Dmitri; the only other person in the house at the time of the murder was Smerdyakov, who was incapacitated due to an epileptic seizure he apparently suffered the day before. As a result of the overwhelming evidence against him, Dmitri is formally charged with the patricide and taken away to prison to await trial.

Book Ten: Boys

Boys continues the story of the schoolboys and Ilyusha last referred to in Book Four. The book begins with the introduction of the young boy Kolya Krasotkin. Kolya is a brilliant boy who proclaims his atheism, socialism, and beliefs in the ideas of Europe. He seems destined to follow in the spiritual footsteps of Ivan Karamazov; Dostoevsky uses Kolya's beliefs especially in a conversation with Alyosha to pick fun at his Westernizer critics by putting their beliefs in what appears to be a young boy who doesn't exactly know what he is talking about. Kolya is bored with life and constantly torments his mother by putting himself in danger. As part of a prank Kolya lies underneath railroad tracks as a train passes over and becomes something of a legend for the feat. All the other boys look up to Kolya, especially Ilyusha. Since the narrative left Ilyusha in Book Four, his illness has progressively worsened and the doctor states that he will not recover. Kolya and Ilyusha had a falling out over Ilyusha's maltreatment of a dog: Ilyusha had fed it bread in which there was a pin on Smerdyakov's suggestion. But thanks to Alyosha's intervention the other schoolboys have gradually reconciled with Ilyusha, and Kolya soon joins them at his bedside. It is here that Kolya first meets Alyosha and begins to reassess his nihilist beliefs.

Book Eleven: Brother Ivan Fyodorovich

Book Eleven chronicles Ivan Karamazov's destructive influence on those around him and his descent into madness. It is in this book that Ivan meets three times with Smerdyakov, the final meeting culminating in Smerdyakov's dramatic confession that he had faked the fit, murdered Fyodor Karamazov, and stolen the money, which he presents to Ivan. Smerdyakov expresses disbelief at Ivan's professed ignorance and surprise. Smerdyakov claims that Ivan was complicit in the murder by telling Smerdyakov when he would be leaving Fyodor's house, and more importantly by instilling in Smerdyakov the belief that in a world without God "everything is permitted." The book ends with Ivan having a hallucination in which he is visited by the devil, who torments Ivan by mocking his beliefs. Alyosha finds Ivan raving and informs him that Smerdyakov killed himself shortly after their final meeting.

Book Twelve: A Judicial Error

This book details the trial of Dmitri Karamazov for the murder of his father Fyodor. The courtroom drama is sharply satirized by Dostoevsky. The men in the crowd are presented as resentful and spiteful, and the women are irrationally drawn to the romanticism of Dmitri's love triangle between himself, Katerina, and Grushenka. Ivan's madness takes its final hold over him and he is carried away from the courtroom after recounting his final meeting with Smerdyakov and the aforementioned confession. The turning point in the trial is Katerina's damning testimony against Dmitri. Impassioned by Ivan's illness which she believes is a result of her assumed love for Dmitri, she produces a drunken letter Dmitri wrote to her saying that he would kill Fyodor. The section concludes with the impassioned closing remarks of the prosecutor and the defense, and the verdict that Dmitri is guilty.

Epilogue

The final section opens with an ambiguous plan developed for Dmitri's escape from his sentence of twenty years of hard labor in Siberia. Dmitri and Katerina meet while Dmitri is in the hospital, recovering from an illness before he is due to be taken away. They agree to love each other for that one moment, and say they will love each other forever, even though both now love other people. The novel concludes at Ilyusha's funeral, where Ilyusha's schoolboy friends listen to Alyosha's "Speech by the Stone." Alyosha promises to remember Kolya, Ilyusha, and all the boys and keep them close in his heart, even though he will have to leave them and may not see them again until many years have passed. He implores them to love each other and to always remember Ilyusha, and to keep his memory alive in their hearts, and to remember this moment at the stone when they were all together and they all loved each other. In tears, the boys promise Alyosha that they will keep each other in their memories forever, join hands, and return to the Snegiryov household for the funeral dinner, chanting, "Hurrah for Karamazov!"

Influence

The Brothers Karamazov has had a deep influence on many writers and philosophers that followed it. Sigmund Freud called it "The most magnificent novel ever written" and was fascinated with the book for its Oedipal themes. In 1928 Freud published a paper titled "Dostoevsky and parricide" in which he investigated Dostoevsky's own neuroses and how they contributed to the novel. Freud claimed that Dostoevsky's epilepsy was not a natural condition but instead a physical manifestation of the author's hidden guilt over his father's death. According to Freud, Dostoevsky (and all sons for that matter) wished for the death of his father because of latent desire for his mother; and as evidence Freud cites the fact that Dostoevsky's epileptic fits did not begin until he turned 18, the year his father died. The themes of parricide and guilt, especially in the form of moral guilt illustrated by Ivan Karamazov, would then obviously follow for Freud as literary evidence of this theory. However, scholars have since discredited Freud's connection because of evidence showing that Dostoevsky's children inherited his epileptic condition, making the cause biological, rather than psychological.

Franz Kafka is another writer who felt immensely indebted to Dostoevsky and The Brothers Karamazov for influencing his own work. Kafka called himself and Dostoevsky "blood relatives," perhaps because of Dostoevsky's existential motifs. Another interesting parallel between the two authors was their strained relationships with their fathers. Kafka felt immensely drawn to the hatred Fyodor's sons demonstrate toward their father in The Brothers Karamazov and dealt with the theme of fathers and sons himself in many of his works, most explicitly in his short story "The Judgment".

James Joyce noted that, "[Leo] Tolstoy admired him but he thought that he had little artistic accomplishment or mind. Yet, as he said, 'he admired his heart', a criticism which contains a great deal of truth, for though his characters do act extravagantly, madly, almost, still their basis is firm enough underneath... The Brothers Karamazov... made a deep impression on me... he created some unforgettable scenes [detail]... Madness you may call it, but therein may be the secret of his genius... I prefer the word exaltation, exaltation which can merge into madness, perhaps. In fact all great men have had that vein in them; it was the source of their greatness; the reasonable man achieves nothing." [1]

In Kurt Vonnegut's novel Slaughterhouse-Five, the eccentric Eliot Rosewater, a science-fiction savant, says that "everything there was to know about life was in The Brothers Karamazov, by Feodor Dostoevsky". David James Duncan's 1992 novel, The Brothers K, takes many ideas from Dostoevsky's story, including the patriarch with four sons, the theme of religious and spiritual uncertainty, and even some character traits of the sons, as well as the eldest son's exile. Duncan was two years into the writing of The Brothers K when he reread Dostoevsky's novel. The "K" of Duncan's title refers to the box-score mark in baseball that indicates a strikeout. Dinaw Mengestu's 2007 novel, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears, uses The Brothers Karamazov as a tool to bond its central characters. One of the novel's themes is also the consideration of the existence of God.

Footnotes

- ↑ Hutchins, Robert Maynard, editor in chief (1952). Great Books of the Western World. Chicago: William Benton.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund Writings on Art and Literature

- ↑ The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 9: The Berlin Years: Correspondence, January 1919 - April 1920

- ↑ Manuel Komroff, "The Brothers Karamazov". New York, NY, 1957.

- ↑ Ralph E. Matlaw, The Brothers Karamazov. New York: W.W. Norton, 1976, 1981

- ↑ Victor Terras, A Karamazov Companion. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981, 2002.

- ↑ David Remnick (7 November 2005). "The Translation Wars", The New Yorker. Retrieved on 2008-04-23.

References

- Mochulsky, Konstantin translation by Minihan, Michael A. (1967). Dostoevsky: His Life and Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Dostoevsky Studies: Kafka and Dostoevsky as "Blood Relatives." http://www.utoronto.ca/tsq/DS/02/111.shtml

- Suzanne Fields (2005). "The new Pope, a good egg, Benedict". URL accessed on August 10, 2007

- Terras, Victor (1981, 2002). A Karamazov Companion. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Text

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor translation by Pevear, Richard and Volokhonsky, Larissa (1990). The Brothers Karamazov. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor, translation by Garnett, Constance, revised by Matlaw, Ralph E. (1976, 1981). The Brothers Karamazov. New York: W.W. Norton.

External links

- The Brothers Karamazov, e-text of Garnett's translation (1.9 MB).

- The Grand Inquisitor at Project Gutenberg

- The Brothers Karamazov Free PDF from PSU's Electronic Classics Series

- The Brothers Karamazov, HTML version of Garnett's translation (as one file) at the CCEL

- Full text in the original Russian

|

||||||||||||||||