Slovaks

| Slovaks |

|---|

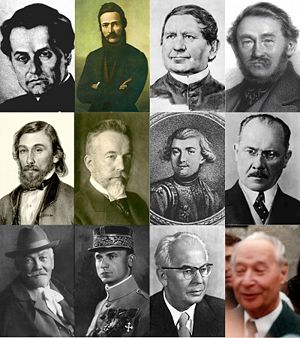

Anton Bernolák, Ľudovít Štúr, Jozef Maximilián Petzval, Štefan Anián Jedlík, Jozef Miloslav Hurban, Aurel Stodola, Móric Beňovský, Milan Hodža, Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav, Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Gustáv Husák, Alexander Dubček Anton Bernolák, Ľudovít Štúr, Jozef Maximilián Petzval, Štefan Anián Jedlík, Jozef Miloslav Hurban, Aurel Stodola, Móric Beňovský, Milan Hodža, Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav, Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Gustáv Husák, Alexander Dubček |

| Total population |

|

~7 million |

| Regions with significant populations |

|

| Languages |

| Slovak |

| Religion |

| Roman Catholic 68.9%, Byzantine Rite Catholic 4.1%, Protestant 10.8%, Eastern Orthodox, other or unspecified 3.2%, no denomination, agnostic or non-religious 13% (2001 census within Slovakia, extrapolated to outside Slovaks) |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other West Slavs |

The Slovaks or Slovakians are a western Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language, which is closely related to the Czech language.

Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia (circa 5,000,000). There are Slovak minorities in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Serbia and sizable populations of immigrants and their descendants in the U.S. and in Canada.

Contents |

History

Early Slovaks

The people of Slovakia are descended from the Slavic settlers of the Danube river basin around 500 C.E. The first known Slavic state on the territory of present-day Slovakia was the Empire of Samo. The first known state of the Proto-Slovaks was the Principality of Nitra founded sometime in the 8th century.

Great Moravia

Great Moravia (833 - ?907) was an ancestral state of the present-day Moravians and Slovaks in the 9th and early 10th century A.D. Its formation and rich cultural heritage attract somewhat more note today due to Slovakia's newfound independence. Important developments took place at this time, including the mission of Cyril and Methodius, the development of the Glagolitic alphabet, an early form of the Cyrillic alphabet, and the use of Old Church Slavonic as the official and literary language.

The original territory inhabited by the (proto-)Slovaks included present-day Slovakia, parts of present-day south-eastern Moravia and approximately the entire northern half of present-day Hungary.

Kingdom of Hungary

Slovakia came under Hungarian rule gradually from 907 to the early 14th century (major part by 1100) and remained a part of the Kingdom of Hungary (see also Upper Hungary or Uhorsko) until the formation of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Politically, Slovakia formed (again) the separate entity called Nitra Frontier Duchy, this time within the Kingdom of Hungary. This duchy was abolished in 1107. The territory inhabited by the Slovaks in present-day Hungary was gradually reduced, but in the 14th century, there were still many Slovak settlements in northern eastern present-day Hungary.

When present-day Hungary was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1541, Slovakia became the core of the "reduced" kingdom, officially called Royal Hungary. Many Magyars (Hungarians) fleeing from present-day Hungary to the north settled in large parts of present-day southern Slovakia, thereby creating the considerable Magyar minority in southern Slovakia today. Some Croats settled around and in present-day Bratislava for similar reasons. Also, many Germans settled in Slovakia, especially in the towns, as work-seeking colonists and mining experts from the 13th to the 15th century. German settlers outnumbered the native populace in almost all towns in the Kingdom of Hungary, but their numbers began to stagnate in the 16th century and to decrease later. Jews and Gypsies also formed significant populations within the territory.

After the Ottoman Empire was forced to retreat from present-day Hungary around 1700, thousands of Slovaks were gradually settled in depopulated parts of the restored Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Hungary, Romania, Serbia, and Croatia) under Maria Theresia, and that is how present-day Slovak enclaves (like Slovaks in Vojvodina) in these countries arose.

After Transylvania, Slovakia was the most advanced part of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries (the most urbanized part, intense mining of gold and silver), but in the 19th century, when Buda/Pest became the new capital of the kingdom, the importance of Slovakia as well as other parts within the Kingdom fell, and many Slovaks were relegated to the indigence. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Slovaks emigrated to North America, especially in the late 19th century and early 20th century (between cca. 1880–1910), and a total of at least 1.5 million (~2/3 of them were part of some minority).

Slovakia exhibits a very rich folk culture. A part of Slovak customs and social convention are common with those of other nations of the former Habsburg monarchy (the Kingdom of Hungary was in personal union with the Habsburg monarchy from 1526 to 1918).

Czechoslovakia

People of Slovakia spent most part of the 20th century within the framework of Czechoslovakia, a new state formed after World War I. Significant reforms and post-World War II industrialization took place during this time. The Slovak language has been strongly influenced by the Czech language during this period.

Contemporary Slovaks

The political transformations of 1989, 1993 and the accession to the EU in 2004 brought new liberties, which have considerably improved the outlook and prospects of all Slovaks.

Contemporary Slovak society organically combines elements of both folk traditions and Western European lifestyles.

Name and ethnogenesis

The Slovaks and Slovenes are the only current Slavic nations that have preserved the old name of the Slavs (singular: slověn) in their name - the adjective "Slovak" is still slovenský and the feminine noun "Slovak" is still Slovenka in the Slovak language, only the masculine noun "Slovak" changed to Slovenin probably in the High Middle Ages and finally (under Czech and Polish influence) to Slovák around 1400. For Slovenes the adjective is still slovenski, the feminine noun "Slovene" is still Slovenka, but the masculine noun has since changed to Slovenec. The Slovak name for their language is slovenčina and the Slovene name for theirs is slovenščina. The Slovak term for the Slovene language is slovinčina; and the Slovenes call Slovak slovaščina.

According to Nestor and modern Slavic linguists, the above mentioned word slověn probably was the original name of all Slavs, but most Slavs (Czechs, Poles, Croats etc.) have taken other names in the Early Middle Ages. Although the Slovaks themselves seem to have had a slightly different word for "Slavs" (Slovan), they were called by Latin texts "Slavs" approximately up to the High Middle Ages. Thus, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish when Slavs in general and when Slovaks are meant. A good proof of the use of "Slavs" in the sense of "Slovaks" are documents of the Kingdom of Hungary which mention Bohemians (Czechs), Poles, Croats "and Slavs" (not: and "other Slavs"), implying that the "Slavs" are Slovaks.

Since this is a very difficult topic, some Slovak "extreme" scholars derive from the above that all references to Slavs in the territory of present-day Slovakia are references to Slovaks (e.g. as early as in the 7th century), while on the other hand, some scholars from Hungary or Czechia derive from the above, that all references to Slovaks are just references to Slavs. The current position of the most prominent Slovak ethnographers and linguists is that the Slavs in the territory of Slovakia have to be called "Slovaks" not later than from 955 or 1000 onwards (when the Magyars settled in Hungary) and that this Slovak ethnogenesis (i.e. separation from the other Slavs) started approximately in the 8th century. Considering, however, that the Slavs that came to present-day Slovakia around 500 are the direct predecessors of present-day Slovaks (they have never been "replaced" by "other" Slavs) and that it is usual today to call the Slovenes, Poles and other nations by their later names well before 1000 (although the ethnic situation is not different from that of the Slovaks at that time), the 1000 limit is rather arbitrary and it is not completely wrong to call the Slavs in this territory "Proto-Slovaks" or "Old Slovaks" or even "Slovaks" even before 1000 in certain contexts.

Quotes from important chronicles

This is how Nestor in his Primary Chronicle (historically correctly) describes the Slovaks: Slavs that were settled along the Danube, which have been occupied by the Hungarians, the Czechs, the Lachs, and Poles that are now known as the Rus. Nestor calls these Slavs "Slavs of Hungary" in another place of the text, and mentions them in the first place in a list of Slavic nations (besides Moravians, Bohemians, Poles, Russians, etc.), because he considers the Carpathian Basin (including what is today Slovakia) the original Slavic territory.

Anonymus, in his Gesta Hungarorum, calls the Slovaks (around 1200 with respect to past developments) Sclavi , i.e. Slavs (as opposed to "Boemy" - the Bohemians, and "Polony" - the Poles) or in another place Nytriensis Sclavi, i.e. Nitrian Slavs.

And this is how Slovaks were called in various very precise sources approximately from 1200 to about 1400: Slovyenyn, Slowyenyny; Sclavus, Sclavi, Slavus, Slavi; Tóth; Winde, Wende, Wenden.

Culture

- See also List of Slovaks

Slovaks have a very rich, old and diverse folk culture (songs, fairy tales, dances), literature, music and art.

The art of Slovakia can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when some of the greatest masterpieces of the country's history were created. Significant figures from this period included the many Masters, among them the Master Paul of Levoča and Master MS. More contemporary art can be seen in the shadows of Koloman Sokol, Albín Brunovský, Martin Benka, Mikuláš Galanda, and Ľudovít Fulla. The most important Slovak composers have been Eugen Suchoň, Ján Cikker, and Alexander Moyzes.

The most famous Slovak names can indubitably be attributed to invention and technology. Such people include Jozef Murgaš, the inventor of wireless telegraphy; Ján Bahýľ, the inventor of the motor-driven helicopter; Jozef Maximilián Petzval, inventor of the camera zoom and lens (although he considered himself an ethnic Hungarian); Jozef Karol Hell (although German by heritage), inventor of the industrial water pump; Štefan Banič, inventor of the modern parachute; Aurel Stodola, inventor of the bionic arm and pioneer in thermodynamics; and, more recently, John Dopyera, father of modern acoustic string instruments. Štefan Anián Jedlík Slovakia is also known for its polyhistors, of whom include Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Matej Bel, Ján Kollár, and its political revolutionaries, such Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Alexander Dubček.

There were two leading persons who codified the Slovak language. The first one was Anton Bernolák whose concept was based on the dialect of western Slovakia (1787). It was the enactment of the first national literary language of Slovaks ever. The second notable man was Ľudovít Štúr. His formation of the Slovak language had principles in the dialect of central Slovakia (1843).

The best known Slovak hero was Juraj Jánošík (the Slovak equivalent of Robin Hood). Prominent explorer Móric Beňovský had Slovak ancestors.

In terms of sports, the Slovaks are probably best known (in North America) for their hockey personalities, especially Stan Mikita, Peter Šťastný, Peter Bondra, Žigmund Pálffy and Marián Hossa. For a list see List of Slovaks.

For a list of the most notable Slovak writers and poets, see List of Slovak authors.

Statistics

There are approximately 4.6 million autochthonous Slovaks in Slovakia. Further Slovaks live in the following countries (the list shows estimates of embassies etc. and of associations of Slovaks abroad in the first place, and official data of the countries as of 2000/2001 in the second place).

The list stems from Claude Baláž, a Canadian Slovak, the current plenipotentiary of the Government of the Slovak Republic for Slovaks abroad (see e.g.: 6) :

- USA (1 200 000 / 821 325*) [*(1)there were, however, 1 882 915 Slovaks in the US according to the 1990 census, (2) there are some 400 000 "Czechoslovaks" in the US, a large part of which are Slovaks] - 19th - 21st century emigrants; see also [10]

- Czech Republic (350 000 / 183 749*) [*there were, however, 314 877 Slovaks in the Czech Republic according to the 1991 census] - due to the existence of former Czechoslovakia

- Hungary (39 266 / 17 693)

- Canada (100 000 / 50 860) - 19th - 21st century migrants

- Serbia (60 000 / 59 021*) [especially in Vojvodina;*excl. the Rusins] - 18th & 19th century settlers

- Poland(2002) (47 000 / 2 000*) [* The Central Census Commission has accepted the objection of the Association of Slovaks in Poland with respect to this number ]- ancient minority and due to border shifts during the 20th century

- Romania (18 000 / 17 199) - ancient minority

- Ukraine (17 000 / 6 397) [especially in Carpathian Ruthenia] - ancient minority and due to the existence of former Czechoslovakia

- France (13 000/ n.a.)

- Australia (12 000 / n.a.) - 20th - 21st century migrants

- Austria (10 234 / 10 234) - 20th - 21st century migrants

- United Kingdom (10 000 / n.a.)

- Croatia (5 000 / 4 712) - 18th & 19th century settlers

- other countries

The number of Slovaks living outside Slovakia in line with the above data was estimated at max. 2 016 000 in 2001 (2 660 000 in 1991), implying that, in sum, there were max. some 6 630 854 Slovaks in 2001 (7 180 000 in 1991) in the world. The estimate according to the right-hand site chart yields an approximate population of Slovaks living outside Slovakia of 1.5 million.

Other (much higher) estimates stemming from the Dom zahraničných Slovákov (House of Foreign Slovaks) can be found here(in Slovak).

References

- Slovaks in the US PDF

- Slovaks in Czech Republic

- Slovaks in Serbia

- Slovaks in Canada

- Slovaks in Hungary

- Baláž, Claude: Slovenská republika a zahraniční Slováci. 2004, Martin

- Baláž, Claude: (a series of articles in:) Dilemma. 01/1999 – 05/2003

See also

- List of Slovaks

- List of Slovak Americans

- Slovaks in Vojvodina

- Slovaks in Bulgaria

- History of the Slovak language

- Slovakia