Skåneland

- This region should not be confused with Skånland in Norway.

Halland Skåne Blekinge |

|

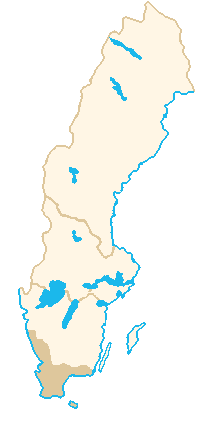

Sweden and part of Denmark, with the historic region Skåneland (the Scanian Provinces) in brown, consisting of the Swedish provinces Blekinge, Halland and Scania, and the Danish island Bornholm |

|

Flag of Skåneland, registered with Scandinavian Roll of Arms as a cultural symbol for the region, in official use by Skåne Regional Council since 1999, and used almost exclusively in the Swedish province Scania. Day of the Scanian Flag is celebrated on the third Sunday in July. |

Skåneland, or Skånelandskapen, (Scanian Provinces in English) are Swedish denominations based on the Latin name Terra Scaniae ("Scania Land"), used for the historical Danish land in southern Scandinavia, which as the autonomous polity Scania joined Zealand and Jutland in the formation of a Danish state in the early 800s.[1] As a cultural and historical region, it consists of the provinces Scania, Halland, Blekinge and Bornholm. It became a Danish province, sometimes referred to as the Eastern Province, after the 12th-century civil war called the Scanian Uprising.[2] The region was part of the territory ceded to Sweden in 1658 under the Treaty of Roskilde, but after an uprising on Bornholm, this island was returned to Denmark in exchange for the ownership of 18 crown estates in Scania. Since Bornholm and the small island of Anholt (once forming part of the parish Morup in Halland) have remained Danish,[3] the Danish part of the historical region is sometimes excluded in modern popular usage of the terms.[4]

Skåneland or Skånelandskapen are the Swedish equivalents to the Danish term Skånelandene. Today, the terms have no political implications as the region is not a geopolitical entity but a cultural region, without officially established political borders. In some circumstances, the term Skåneland, as opposed to the terms Skånelandskapen and Skånelandene, can also be used as a figure of speech for the province Scania, which has the only administrative entities connected to the name, namely Region Skåne and Skåne County, both created in the late 1990s.

Contents |

Official status

When Skåneland was an official entity, in its original Danish province configuration, its status was determined by the Danish king and the administrative authority under which it was governed, namely the Scanian Thing. Each of the four provinces of Skåneland had representation in the Scanian Thing, which, along with the other two Things of the Danish state (Jutland and Zealand), elected the Danish king.

Skåneland's four provinces were joined under the jurisdiction of the Scanian Law, dated 1200–1216,[5] the oldest Nordic provincial law. In the chapter "Constitutional history" in Danish Medieval History, New Currents, the three provincial Things are described as being the legal authority that instituted changes suggested by the elected king. The suggestions for changes submitted by the king had to be approved by the three Things before being passed into law in the Danish state.[2]

Status today

Skåneland has no political representation, but is strictly a historic and cultural region. Even though the Danish term Skånelandene is still used in official contexts in Denmark,[6] the use of the term in Sweden is not universally accepted,[7] although it has long appeared as a term used in historical contexts in a variety of sources.[8][9] With the exception of Region Skåne and Västra Götalandsregionen, the Swedish provinces are not officially divided into regional units or referred to as regions; instead, the names of the individual provinces are used in official contexts. The southern part of Sweden, including Skåneland, is considered to be included in Götaland, one of three historic "lands of Sweden". The "land" Götaland bears the same name used for the historic province Götaland (a province referred to as "Gothia" on the 17th-century maps); the inclusion of Skåneland is described as "historically inaccutare" by the Swedish Nationalencyklopedin.[7]

The term "Skåneland" is sometimes resisted in Sweden as being an expression of regionalism. As in other cultural regions, regionalism in Scania sometimes has a base in regional nationalism and sometimes in a more general opposition against centralized state nationalism or expansionist nationalism. In Scania, Swedish nationalism, which often alludes to slogans such as "Keep Sweden Swedish", is resisted by many regionalists as being intolerant of Scania's cultural diversity and Danish history, and as being non-inclusive of cultural expressions originating in areas outside the capital region. As noted about regionalism in Norway, Scandinavian regionalism is not necessarily separatist.[10]

Origin of the name

Origin of Latin name

The Latin names Scaniæ, Scania and Scandia is often believed to have the same etymology as Scandinavia, a name first appearing in Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia.[11] Pliny spelled the name Scatinavia and used it for Scania or the southern part of the Scandinavian peninsula, which he believed to be an island. Pliny wrote about the Hilleviones residing in 500 villages on this "island" (Book 4, Chapter 27), and the idea that the Hilleviones constituted an early population of Halland has gained acceptance among some scholars.[12] If so, the tribe could be the same as the Hallin of Scandza, who are mentioned by Jordanes.

The use of the name Scandia for Skåneland or the southern part of the Scandinavian peninsula is primarily found in Greek tradition and appeared in this meaning for the first time in Ptolemy's writings during the second century AD.[13] Ptolemy used the name Skandia to denote the main island in an island group he called Skandiai located by Cimbri, at the same location where Pliny the Elder placed Scatinavia. Pliny the Elder also mentioned an island called Scandia, but identified it as a different island from Scatinavia.

The use of the name Scandinavia for the Nordic countries only appeared in the 18th century, when it was adopted as a convenient general term for the entire peninsula region of which Skåneland or Scania was part.[14]

The term Scaniae, or Terra Scaniae, was reintroduced during the Middle Ages as a denomination for the region then forming the easternmost parts of Denmark.[15] At that time, dense forests and boggy ground blocked the southern provinces of Sweden from Skåneland, in comparison to the relative ease of travel by sea. It was therefore natural to draw the national borders on land. This is documented by Adam of Bremen in the 11th century when he visited Scania and Scandinavia and called it the richest and most important part of Denmark. Even in later periods as the roads gradually improved, some parts were still difficult to travel through, even through the 19th century.[16]

Origin of Swedish name

The Swedish Academy lists examples[17] of the usage of Skåneland in documents from as early as 1719, and from 1759 (by Carl von Linné). In many later examples of Swedish usage, Bornholm is no longer included. The Swedish term "Skåneland" has thus been used since at least the 1700s[17], but it was popularized by the Swedish historian and Scandinavist Martin Weibull in his political appeal Samlingar till Skånes historia in 1868 in order to illuminate the common pre-Swedish history of Skåne, Blekinge, and Halland. The term is basically a translation from the medieval Latin terra Scaniæ ("land of Skåne" or "Scania Land"). Weibull used the term as a combined term for the three provinces where Skånelagen ("The Scanian law", the oldest provincial law of the Nordic countries) had its jurisdiction, as well as the area of the archdiocese of Lund until the Reformation in 1536, later the Danish Lutheran diocese of Lund. This form of Skåneland was then used in the regional historical periodical Historisk tidskrift för Skåneland, beginning in 1901, published by Martin's son, Lauritz Weibull.[18]

Modern usage

The collective terms Skåneland or Skånelandskapen for the provinces are uncommon in state issued texts, but regionally revived notions of a common cultural heritage have made the usage more prominent; the terms are in general use among historians focused on the centuries immediately before and after 1658, and are often used in professional, peer-reviewed journals and history magazines aimed at the general public.[9]

The term Skåneland (Scania) is also used to denote the area accepted as an unrepresented nation into UNPO (Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation)[19] and FUEN (Federal Union of European Nationalities),[20] and in order to differentiate it from the historical province Scania proper (Skåne), the now Swedish province Scania (Skåne) and from the administrative Scania County (Skåne län), established in 1998 after having been split into Malmöhus County and Kristianstad County between 1719 and 1997.

In UNPO, Scania, like many other historic regions, is currently represented by a NGO, in the case of Scania, the private foundation Stiftelsen Skånsk Framtid (Scania Future Foundation).

The modern usage is mostly found in historical research as a way to refer to the common culture, language and history of Skåne, Blekinge, Halland and Bornholm before the Swedish acquisition of Skåne, Blekinge and Halland, as a way to stress the culturally unique features of the region. Although the term is rarer in official contexts, recent interest has spurred the national broadcaster Sveriges Television to examine the concept and the word is therefore becoming more familiar in Sweden.[21]

History

Early history

From 1104 the Danish archbishop had his residence in Lund; and it was also here the first Danish university was founded, the Lund Academy (1425–1536).

The earliest Danish historians, writing in the 12th and 13th century, believed that the Danish Kingdom had existed since king Dan, in a distant past. Eighth century sources mention the existence of Denmark as a kingdom. According to 9th century Frankish sources, by the early 9th century many of the chieftains in the south of Scandinavia acknowledged Danish kings as their overlords, though kingdom(s) were very loose confederations of lords until the last couple medieval centuries saw some increased centralization. The west and south coast of modern Sweden was so effectively part of the Danish realm that the said area (and not the today Denmark) was known as "Denmark" (literally the frontier of the Daner).[22][23] Svend Estridsen (King of Denmark 1047 – ca. 1074), who may have been from Scania himself, is often referred to as the king who along with his dynasty established Scania as an integral, and sometimes the more important, part of Denmark.

However, historians also argue that in the loose conditions of medieval kingdom-building of the 10th and 11th centuries, Scania sometimes attached itself to the Swedish kingdom instead of the Danish. In 1330s–1360s, Scania was held as the "third kingdom" by Magnus VII of Norway and Sweden, as a result of temporary dissolution of Danish central government. He was, from 1335, titled rex Suecie, Norwegie et Scanie or regnorum svechie et norwegie terreque scanie rex.

From the Kalmar Union to Denmark's Loss of Skåne, Blekinge and Halland

When the Kalmar Union was formed in 1397, the union was administered from Copenhagen. By 1471 Sweden rebelled under Sture family leadership. In 1503, when Sten Sture the Elder died, eastern Sweden’s independence from Denmark had been established.[24]

In 1600 Denmark controlled virtually all land bordering on the Skagerrak, Kattegat, and the restricted Sound (Øresund). The current Swedish provinces of Skåne, Blekinge and Halland were still Danish and the province of Båhuslen was still Norwegian. Skåneland became the site of bitter battles, especially in the 16th, 17th and 18th century, as Denmark and Sweden confronted each other for control of the Baltic and of Swedish access to western trade. Danish historians often represent this as a period of unending Swedish aggression during which Sweden was continuously at war, while Swedish historians often represent this as "Sweden's Age of Greatness".[25][26][27][28][29]

Sweden intervened in the Danish civil war known as the Count's Feud (1534–1536), launching a highly destructive invasion of Skåneland as the ally of King Christian III. Subsequently, in the period between the breakup of the Kalmar Union and 1814, Denmark and Sweden fought 11 times in Skåneland and other border provinces: 1563–70, 1611–1613, 1644–1645, 1657–1658; 1659–1661, 1674–1678, 1700, 1710–1721, 1788, 1808–1809, and 1814.[30][31][28][27]

- During the Northern Seven Years' War, attacks were launched on Sweden from Danish Halland in 1563, and Swedish counterattacks were launched against Danish provinces of Halland and Skåne in 1565 and 1569. In 1570 peace was finally agreed when the Swedish king withdrew the claims to Danish Skåne, Halland, Blekinge and Gotland, while the Danes withdrew their claims to Sweden as a whole.[28][27][32]

- During the Thirty Years' War extensive combat took place in the Danish provinces of Skåne, Halland, and Blekinge. By the Peace of Brömsebro (1645) Denmark ceded the Norwegian provinces of Jämtland and Härjedalen and agreed Sweden was to occupy the Danish province of Halland for 30 years as a guarantee of the treaty provisions.[28][27]

- During what has been described as the Northern War (1655–1658), Danish attempts to recover control of Halland ended in a serious defeat administered by Sweden. As a result, in the Treaty of Roskilde (1658) Denmark ceded the provinces of Skåne, Blekinge and Halland (i.e., Skåneland).[27]

Vilhelm Moberg, in his history of the Swedish people, provides a thoughtful discussion of the atrocities which were committed by both sides in the struggle over the border provinces, and identified them as the source of propaganda to inflame the peoples’ passions to continue the struggle. These lopsided representations were incorporated into history text books on the respective sides. As an example, Moberg compares the history texts he grew up with in Sweden which represented the Swedish soldier as ever pure and honorable to a letter written by Gustavus Adolphus celebrating the 24 Scanian parishes he had helped level by fire, with the troops encouraged to rape and murder the population at will, behavior that may well have been mirrored equally on the Danish side. Skåneland was a rather unpleasant place to dwell for an extended period.[30]

Assimilation with Sweden

Following the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658 – but in direct contradiction of its terms – the Swedish government in 1683 demanded that the elite groups (nobility, priests and burghers) in Skåneland accepted Swedish customs and laws. Swedish became the only language permitted in the Church liturgy and in schools, religious literature in Danish was not allowed to be printed, and all appointed politicians and priests were required to be Swedish. However the last Danish bishop, Peder Winstrup remained in charge of the Diocese of Lund until his death in 1679. To promote further Swedish assimilation the University of Lund was inaugurated in 1666; the inhabitants of Scania were not allowed to enroll in Copenhagen University until the 19th century.[16]

The population was initially opposed to the Swedish reforms, as can be ascertained from church records and court transcripts. The Swedes did encounter civil revolts in some areas, perhaps most notably in the Göinge district, in dense forest regions of northern Scania. The Swedish authorities resorted to extreme measures against the 17th-century rebels known as the "Snapphane", including the use of impalement, in which a stake was inserted between the spine and the victim's skin, the use of wheels to crush victims alive, as well as the nailing of bodies to church doors. In that way, it could take four to five days before the victim died.[33]

The transformation of age-old customs, commerce and administration to the Swedish model could not be effected quickly or easily. In the first fifty years of the transition, the treatment of the population was rather ruthless. Denmark made several attempts to recapture the territories – the last in 1710, during which it almost recovered the entire Skåneland.[25]

Before 1658, one of the provinces of Skåneland, Scania proper, had consisted of four counties: the counties of Malmöhus, Landskrona, Helsingborg and Kristianstad. When Skåneland was annexed by Sweden, one of the counties of the Scania proper, Kristianstad County, was merged with Blekinge to form one of a total of three Blekinge counties.

Bornholm Rebellion

In 1658, shortly after the Swedish general Printzenskiold was sent to Bornholm to start the "Swedification" process, the population of Bornholm rebelled against their new masters. Led by Jens Kofoed and Poul Anker, the rebellion formed in the town of Hasle, north of the largest city, Rønne. Before the rebel army reached the Swedish headquarters in Rønne, Printzenskiold was shot by Willum Clausen in the street of Sølvgade, in central Rønne. The Swedish fled the island as a result of the confusion and fear amongst the conscripts; Jens Kofoed installed an intermediate rule and send a message to King Frederick III of Denmark that Bornholm had liberated itself, and wished to return to Danish rule. This was confirmed in the 1660 peace settlement between Denmark and Sweden.[34][35]

Swedish administration

- Further information: Swedish Governors-General

Sweden appointed a Governor General, who in addition to having the highest authority of the government, also was the highest military officer. The first to hold the post of Governor General was Gustaf Otto Stenbock, between 1658 to 1664.[36] His residence was in the largest city, Malmö.

The office of Governor General was abandoned in 1669, deemed unnecessary. However, when the Scanian War erupted in 1675, the office was reinstated, and Fabian von Fersen held the office between 1675 to 1677, when he died in the defence of Malmö.

He was replaced by Rutger von Ascheberg, in 1680, who held it to his death in 1693. It was during Ascheberg's time in office that the stricter policy of Swedification was initiated, as a reaction to the threats of war and possible Danish repossession.

Following the death of Ascheberg, the Governor Generalship was dismantled into a separate county governor for each of the Swedish provinces Blekinge, Halland and Scania.[37] However, a Governor Generalship was reinstated in the province of Scania during the Napoleonic War, when Johan Christopher Toll became the last Governor-General in the region, a post he held 1801–09.

Recent history

The complete history of Skåneland was not taught for a long time in schools in Skåneland, especially during periods with the immediate threat of revolt. Instead a Swedish-centric history was taught, and the Scanian history before 1658, for instance concerning the list of monarchs, was disregarded as a component of Danish history. In reaction, a movement began in the late 19th century to revive awareness of the history and culture of Skåneland. The renewed focus resulted in the publication of several books about Scanian history.[16]

It is still disputed whether children of the Scanian provinces should learn the local Danish-era history or the Swedish history for the period before 1658. Proposals from representatives of the Scanian constituencies in the Swedish parliament to include Scanian history in the curriculum of Scanian schools have not been accepted in the decision-making plenary meetings at the Swedish Riksdag in Stockholm.[38][39]

Scanian regionalism

In addition to the preservation of Scanian culture and attention to Scanian history, most of the regionalist movements in Scania also advocate greater autonomy for regions like Skåneland within the current power structure, and thus more independence for the local councils in relation to the central government in Stockholm. The main thrust for most groups is thus not separatism, but decentralization and more local involvement in policy questions affecting the region.

This form of regionalism has a long history in Skåneland, starting in the days of armed resistance and political maneuvering in the Scanian Thing against the rise of Danish absolutism in the 13th century. It showed up again as the driving force in the peasant peace agreements between villages on either side of the Swedish-Danish border during the 17th–18th century, especially during the Scanian War, when the people along the border defied orders and offered shelter and support to each other during the assaults from the Swedish and Danish kings' troops.[40] It emerged again in the general support of the local peasant irregulars who joined the Snapphane guerilla movement against Sweden, and in the silent resistance from priests in their support of the parishioners during the most brutal periods of the "Swedification" process.[41] It also resulted in open rebellion, the last being the larger scale peasant rebellion against the Swedish king and state in 1811, when the king ordered 15,000 Scanian peasants to fight a war they wanted no part of.[42]

The Scanian regionalist movements embrace a host of different ideas for the region, ranging from support for the current regional county council model to opposition to it. Opponents criticize the regional council for its alleged role in diffusing the local support for more radical changes to the current political power structure, and for being too reliant on the party loyalty politics and centralist impulses from the Swedish capital, which are blamed for the lack of development and vision in the region. It also includes groups supporting a Swedish republic, but the federalists are a minority in Scania. The Scanian federalist party, Skånefederalisterna, received only 732 votes in the last election to the regional council. The long amalgamation of Skåneland with Sweden would suggest that the area is generally "Swedified", and that separatism represents a minority viewpoint.

A national trend towards state nationalism has also affected Scania, with the right-wing Swedish state-nationalist party Sverigedemokraterna voted into Scania's regional council in the 2006 election. The same situation is reflected around the country; the party took seats in around half of Sweden's local councils and is now receiving state support.[43]

The strong regionalist tendencies in today's Scania are in general not separatist, as demonstrated in 2006, at the end of the first trial period of the Skåne Regional Council (formed in 1999) in the newly established Scania county, created in 1998. The regional council model had solid support in Scania, in contrast to other counties, with the exception of Västra Götaland Regional Council.

See also

- History of Denmark

- History of Sweden

- Lands of Denmark

- Lands of Sweden

- Dominions of Sweden

- Sweden proper

Notes

- ↑ Thurston, Tina L. (1999). "The knowable, the doable and the undiscussed: tradition, submission, and the 'becoming' of rural landscapes in Denmark's Iron Age". Dynamic Landscapes and Socio-political Process. Antiquity, 73, 1999: 661-71. (On pp. 662-3, Dr. Thurston, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, SUNY-Buffalo, quotes Sten Tesch, archaeologist and head of Sigtuna Museum, and Märta Strömberg, Professor Em., Archaeology and Ancient History, Lund University: "Scania, [...] now part of modern Sweden, was, until 1658, a province of the Danish state, and has been rightly called 'a prehistoric country in the process of dissolution' (Strömberg 1977: 3) with a 'hidden, but disappearing cultural landscape’ (Tesch et al. 1980: 9), for at one time it was an autonomous polity with a distinct ethnic identity, and despite intensive modern farming the Iron Age 'country' is still remarkably preserved as a relict cultural landscape". See also p. 277: "Scania—Skåneland, Cultural region in Scandinavia and Europe."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hoffmann, Erich (1981). "The Unity of the Kingdom and the Provinces in Denmark During the Middle Ages." In Skyum-Nielsen, Niels and Niels Lund, eds. (1981). Danish Medieval History, New Currents. Museum Tusculanum Press, ISBN 8788073300. (On p. 101, Dr. Hoffmann, Professor at University of Kiel, argues that the contemporary descriptions of Scania as an autonomous polity had merit; Scania was often disagreeing in the choice of kings, which resulted in several, simultaneously elected kings in the early Danish state. Scania became officially integrated as a province in the late 12th century, with the Treaty of Lolland.

- ↑ According to local legend, the island of Anholt was simply "overlooked" when the final treaty was executed, as recounted on the official page for Anholt Turist- og Erhvervskontor, Uddrag af Anholts historie (in Danish): "Ved freden i Roskilde i 1658 måtte Danmark afstå Skåne, Halland, Blekinge og Bornholm til Sverige. Det siges at Anholt da ved et tilfælde forblev dansk, idet en af de danske forhandlere holdt sin hånd på landkortet så den dækkede Anholt. Eller var det, som det også fortælles, et krus øl?" ("At the peace in Roskilde 1658, Denmark had to give up Scania, Halland, Blekinge and Bornholm to Sweden. It is said that Anholt at the occasion remained Danish because the Danish negotiator held his hand on the map so that it covered Anholt. Or was it, as is also told, a mug of beer?".

- ↑ For popular usage, see for example the publication Populärhistoria: Hjälpreda om Skåneland: "Skåneland, d v s Halland, Skåne och Blekinge", Fredsfördraget firas i Altranstädt: "Sverige ingick mot slutet av århundradet i en västeuropeisk allians med Holland och England och kunde därigenom stoppa Danmarks revanschplaner för förlusten av Skåneland", Ett liv fyllt av skandaler: "År 1660, då Marie Grubbe anlänt till Köpenhamn, satt Fredrik III på Danmarks tron. Det var han som hade förlorat Skåneland till Sverige vid Roskildefreden 1658".

- ↑ Damsholt, Nanna. "Women in Medieval Denmark". In Skyum-Nielsen, Niels and Niels Lund, eds. (1981). Danish Medieval History, New Currents. Museum Tusculanum Press, ISBN 8788073300: p. 76.

- ↑ See for example the official site for the Danish Monarchy, the section Kongehusets historie: Kongerækken (The Royal Lineage), where the sub-section "Frederik IV" mentions the king’s abandonment of hope to regain Skånelandene ("opgivelse af håbet om generobring af Skånelandene"). Also see the Danish National Archives for documents relating to Skånelandene, for example Lensregnskaberne 1560-1658: "De vigtigste len i Skånelandene var: Helsingborg, Malmøhus, Landskrone, Christianstad, Varberg, Laholm, Halmstad, Froste herred, Christianopel, Sølvitsborg".)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Götaland" (2007). Nationalencyklopedin, 5 February 2008, (in Swedish): "Ehuru historiskt oegentligt, kom även Skåne, Halland, Blekinge och Bohuslän att räknas dit." (Although historically inaccurate, Scania, Blekinge and Bohuslän came to be counted [as part of Götaland]".

- ↑ Thurston, Tina L. (2001). Landscapes of Power, Landscapes of Conflict: State Formation in the South Scandinavian Iron Age. Kluwer Academic, NY, ISBN 0306463202. "Scania—Skåneland, Cultural Region in Scandinavia and in Europe", p. 277.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Skåneland". In Nationalencyklopedin. For usage in the Swedish publication Populär Historia, see Hjälpreda om Skåneland, Fredsfördraget firas i Altranstädt: "Sverige ingick mot slutet av århundradet i en västeuropeisk allians med Holland och England och kunde därigenom stoppa Danmarks revanschplaner för förlusten av Skåneland", Ett liv fyllt av skandaler: "År 1660, då Marie Grubbe anlänt till Köpenhamn, satt Fredrik III på Danmarks tron. Det var han som hade förlorat Skåneland till Sverige vid Roskildefreden 1658". For a recent example of academic usage, see Medeltida danskt järn, framställning av och handel med järn i Skåneland och Småland under medeltiden.

- ↑ Vikør, Lars S. (2000). "Northern Europe". In Language and Nationalism in Europe. Eds. Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198236719, p. 117: "Norway is a country were regionalism has always been strong, [...] a regionalism without any traces of separatism. The idea of unity in diversity has always been exceptionally strong in Norway".

- ↑ Skåne (Historia) - in Nordisk Familjebok (1917)

- ↑ Scandia, Scandinavia Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898)

- ↑ Forte, Angelo, Richard Oram and Frederick Pedersen (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521829925, p. 19.

- ↑ Østergård, Uffe (1997). "The Geopolitics of Nordic Identity – From Composite States to Nation States". The Cultural Construction of Norden. Øystein Sørensen and Bo Stråth (eds.), Oslo: Scandinavian University Press 1997, 25-71. Also published online at Danish Institute for International Studies.

- ↑ See for example Saxo Grammaticus: Gesta Danorum.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Skånelands historia, ved Ambrius, J, 1997 ISBN 91-971436-2-6

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Skåneland in Svenska Akademiens Ordbok (SAOB) on the Internet, and Skåneland in Nordisk Familjebok.

- ↑ Swedish National Encyclopedia article Skånelandskapen

- ↑ Scania - from UNPO Official Website. Accessed September 4, 2008

- ↑ FUEN No. 73 - The Scanians in the Scania region. Accessed September 4, 2008

- ↑ Sveriges Television. Del 3: Skåneland. Svenska Dialektmysterier. SVT Online, 25 Jan. 2006. In Swedish. Retrieved 17 Dec. 2006.

- ↑ Medieval Scandinavia, by Bridget and Peter Sawyer, University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

- ↑ Kings and Vikings, by P.H. Sawyer, Routledge, 1982. (Sawyer considered sources such as Saxo Grammaticus and Snorri Sturluson but validated their material against contemporary primary documents of the period).

- ↑ Sweden and the Baltic, 1523 - 1721, by Andrina Stiles, Hodder & Stoughton, 1992 ISBN 0-340-54644-1

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 A History of Sweden by Ingvar Andersson, Praeger, 1956

- ↑ Nordens Historie, ved Hiels Bache, Forslagsbureauet i Kjøbenhavn, 1884.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 The Northern Wars, 1558-1721 by Robert I. Frost; Longman, Harlow, England; 2000 ISBN 0-582-06429-5

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 The Struggle for Supremacy in the Baltic: 1600-1725 by Jill Lisk; Funk & Wagnalls, New York, 1967

- ↑ Sweden; the Nation's History", by Franklin D. Scott, Southern Illinois Press, 1988.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Min Svenska Historia II, by Vilhelm Moberg, P.A. Nordstedt & Söners Förlag, 1971.

- ↑ The most notable periods of combat for Skåneland were the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–1570), the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and the Northern War (1655–1658).

- ↑ Fra Bondeoppbud til Legdshær by Trygve Mathisen, Guldendal Norsk Forlag, 1952

- ↑ Herman Lindquist (1995). Historien om Sverige – storhet och fall. Norstedts Förlag, 2006 (ISBN 9113015354) (In Swedish), Sixten Svensson (2005). Sanningen om Snapphanelögnen. (ISBN 9197569518) (in Swedish), and Sten Skansjö (1997). Skånes historia. Lund (ISBN 9188930955) (in Swedish).

- ↑ (English) The Swedish Period - revolt against the Swedes - from bornholminfo.dk, a website of TV 2 (Denmark)-Bornholm and Destination Bornholm - an organisation for tourist enterprises on Bornholm. Accessed September 5, 2008.

- ↑ (Danish) 1658 - opstanden på Bornholm - Bornholms Museum, pp.1-6. Accessed September 5, 2008.

- ↑ Gustafsson, Harald (2003). "Att göra svenskar av danskar? Den svenske integrationspolitikens föreställningsvärld 1658-1693". Da Østdanmark blev Sydsverige. Otte studier i dansk-svenske relationer i 1600-tallet. Eds. Karl-Erik Frandsen and Jens Chr.V. Johansen. Narayana Press. ISBN 87 89224 74 4, p. 35-60.

- ↑ Terra Scania website, Terra Scania website, article Skåne Län Efter 1658 in Swedish.

- ↑ Wallin, Gunnel (1999). "Motion Skånelands och andra regioners historia". Motion till riksdagen 1999/2000:Ub239. (In Swedish). Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ↑ Roslund, Carl-Axel (2003). Motion Skånsk historia. 2003/04:Ub277. For previous proposals, see: Motion 2002/03:N340, Motion 2001/02:Ub224, Motion 2000/01:Ub208, Motion 1999/2000:Ub239, Motion 1999/2000:Ub240, Motion 1998/99:Ub204, Motion 1997/98:Ub203, Motion 1996/97:Ub202, Motion 1994/95:Ub301, Motion 1992/93:Ub491. (In Swedish). Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ↑ Andrén, Anders (2000). Against War! Regional Identity Across a National Border in Late Medieval and Early Modern Scandinavia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Vol. 4:4, Dec. 2000, pp. 315-334. ISSN 1092-7697.

- ↑ Alenäs, Stig (2003). Loyalty - Rural Deans - Language Studies of 'Swedification' in the Church in the Lund Diocese during the 1680s (Lojaliteten, prostarna, språket. Studier i den kyrkliga "försvenskningen" i Lunds stift under 1680-talet). Dissertation 2003, Lund Universitety.

- ↑ "Peasant Rebellion and War". In The Agricultural Revolution. Educational material for Scanian and Danish highschools, produced by Oresundstid.

- ↑ SR International - Radio Sweden. "Sweden Democrats to Collect State Support". Sveriges Radio, 21 Nov. 2006. Retrieved 17 Dec. 2006.

References

- Alenäs, Stig (2003). Loyalty - Rural Deans - Language Studies of 'Swedification' in the Church in the Lund Diocese during the 1680s. (Lojaliteten, prostarna, språket. Studier i den kyrkliga "försvenskningen" i Lunds stift under 1680-talet). Dissertation 2003, Lund Universitety.

- Ambrius, J (1997). Skånelands historia, ISBN 91-971436-2-6

- Andersson, Ingvar (1956). A History of Sweden. Praeger, 1956

- Andrén, Anders (2000). "Against War! Regional Identity Across a National Border in Late Medieval and Early Modern Scandinavia". International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Vol. 4:4, Dec. 2000, pp. 315-334. ISSN 10927697.

- Bache, Niels (1884). Nordens Historie. Forslagsbureauet i Kjøbenhavn, 1884.

- Damsholt, Nanna (1981). "Women in Medieval Denmark". In Danish Medieval History, New Currents. Eds. Niels Skyum-Nielsen and Niels Lund. Museum Tusculanum Press, 1981. ISBN 8788073300.

- "Del 3: Skåneland. Svenska Dialektmysterier. SVT Online, 25 January 2006

- Eringsmark Regnéll, Ann-Louise (2006). "Fredsfördraget firas i Altranstäd". Populär Historia, online edition, 31 August 2006.

- Forte, Angelo, Richard Oram and Frederick Pedersen (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521829925.

- "Frederik IV", Kongehusets historie: Kongerækken. The Danish Monarchy.

- Frost, Robert I. (2000). The Northern Wars, 1558-1721. Longman, Harlow, England; 2000 ISBN 0-582-06429-5

- "Götaland" (2007). Nationalencyklopedin, 5 February 2008.

- Gustafsson, Harald (2003). "Att göra svenskar av danskar? Den svenske integrationspolitikens föreställningsvärld 1658-1693". Da Østdanmark blev Sydsverige. Otte studier i dansk-svenske relationer i 1600-tallet. Eds.Karl-Erik Frandsen and Jens Chr.V. Johansen. Narayana Press. ISBN 87 89224 74 4, p. 35-60.

- Hoffmann, Erich (1981). "The Unity of the Kingdom and the Provinces in Denmark During the Middle Ages". In Danish Medieval History, New Currents. Eds. Niels Skyum-Nielsen and Niels Lund. Museum Tusculanum Press, ISBN 8788073300.

- "Lensregnskaberne 1560-1658". Danish National Archives.

- Lindquist, Herman (1995). Historien om Sverige – storhet och fall. Norstedts Förlag, 2006. ISBN 9113015354.

- Lisk, Jill (1967). The Struggle for Supremacy in the Baltic: 1600-1725. Funk & Wagnalls, New York, 1967.

- Mathisen, Trygve (1952). Fra Bondeoppbud til Legdshær. Guldendal Norsk Forlag, 1952.

- Moberg, Vilhelm (1971). History of the Swedish People Vol. 2: From Renaissance to Revolution. Transl. Paul Britten Austin, University of Minnesota Press, 2005, ISBN 0816646570. (Swedish original: Min Svenska Historia II. Nordstedt & Söners Förlag, 1971).

- Olsson, Sven-Olof (1995). Medeltida danskt järn, framställning av och handel med järn i Skåneland och Småland under medeltiden. Halmstad University. ISBN 9197257907.

- Østergård, Uffe (1997). "The Geopolitics of Nordic Identity – From Composite States to Nation States". The Cultural Construction of Norden. Øystein Sørensen and Bo Stråth (eds.), Oslo: Scandinavian University Press 1997, 25-71.

- "Peasant Rebellion". In The Agricultural Revolution. Educational material for Scanian and Danish highschools, produced by Oresundstid.

- Petrén, Birgitta (1995). "Ett liv fyllt av skandaler". Populär Historia 2/1995.

- Roslund, Carl-Axel (2003). Motion Skånsk historia. 2003/04:Ub277. (In Swedish).

- Sawyer, Bridget and Peter (1993). Medieval Scandinavia. University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

- Sawyer, P.H. (1982). Kings and Vikings. Routledge, 1982.

- Saxo Grammaticus. Gesta Danorum. Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Denmark.

- Scott, Franklin D. (1988). Sweden; the Nation's History. Southern Illinois Press, 1988.

- "Skånelandskapen" (2008). In Nationalencyclopedin.

- "Skåneland" (1917). In Nordisk Familjebok.

- "Skåneland" (2008). In Svenska Akademiens Ordbok (SAOB)

- Skansjö, Sten (1997). Skånes historia. Lund, ISBN 9188930955.

- Stiles, Andrina (1992). Sweden and the Baltic, 1523 - 1721. Hodder & Stoughton, 1992. ISBN 0-340-54644-1.

- Svensson, Sixten (2005). Sanningen om Snapphanelögnen. ISBN 9197569518.

- "Sweden Democrats to Collect State Support". Sveriges Radio, 21 November 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- Thurston, Tina L. (2001). Landscapes of Power, Landscapes of Conflict: State Formation in the South Scandinavian Iron Age. Kluwer Academic, NY, ISBN 0306463202.

- Thurston, Tina L. (1999). "The knowable, the doable and the undiscussed: tradition, submission, and the 'becoming' of rural landscapes in Denmark's Iron Age". Dynamic Landscapes and Socio-political Process. Antiquity, 73, 1999: 661-71

- Vikør, Lars S. (2000). "Northern Europe". In Language and Nationalism in Europe. Eds. Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198236719.

- Wallin, Gunnel (1999). "Motion Skånelands och andra regioners historia". Motion till riksdagen 1999/2000:Ub239. (In Swedish)

External links

- Scania at UNPO - Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation - an international organization for unrecognized regions

- Scania - Scania Future Foundation, a regionalist organization in Scania

- Terra Scaniae - a history project for Middle- and Highschool educators, supported by Region Scania's culture department – Kultur Skåne – and the Foundation Culture of the Future, established by the Swedish Government.

- Codex Runicus - a manuscript from c. 1300 containing Scanian law

- Øresundstid - a cooperative educational project established by Scanian and Danish history teachers, funded by EUs InterregIIIA-program, the Danish Department of Education and others, 2004-2006.

- Magnus of Norway and Sweden titled as King of Terra Scania - a history site

- Vår mörklagda historia - a history site

- Scania Institute - a regionalist organization in Halland

- Föreningen Skånelands Framtid - a cultural, regionalist organization in Scania

- Danish-Scanian Organization - a cultural, regionalist organization in Denmark

- Skaansk Fremtid - a cultural, regionalist organization in Denmark

- Skåneland on the web - links to various Scanian regionalist websites

- Scanian federalist party - a political party in Scania