Walter Scott

| Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet | |

|---|---|

Raeburn's portrait of Sir Walter Scott in 1822. |

|

| Born | 15 August 1771 Edinburgh, Scotland, Great Britain |

| Died | 21 September 1832 (aged 61) Melrose, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Historical novelist, poet |

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832) was a prolific Scottish historical novelist and poet popular throughout Europe during his time.

In some ways Scott was the first English-language author to have a truly international career in his lifetime, with many contemporary readers all over Europe, Australia, and North America. His novels and poetry are still read, and many of his works remain classics of both English-language literature and of Scottish literature. Famous titles include Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, The Lady of The Lake, Waverley, The Heart of Midlothian and The Bride of Lammermoor.

Contents[hide] |

Early days

Born in College Wynd in the Old Town of Edinburgh in 1771, the son of a solicitor, the young Walter Scott survived a childhood bout of polio in 1773 that would leave him lame. To cure his lameness he was sent in that year to live in the rural Borders region at his grandparents' farm at Sandyknowe, adjacent to the ruin of Smailholm Tower, the earlier family home. Here he was taught to read by his aunt Jenny, and learned from her the speech patterns and many of the tales and legends which characterized much of his work. In January 1775 he returned to Edinburgh, and that summer went with his aunt Jenny to take spa treatment at Bath in England. In the winter of 1776 he went back to Sandyknowe, with another attempt at a water cure being made at Prestonpans during the following summer.[1]

In 1778 Scott returned to Edinburgh for private education to prepare him for school, and in October 1779 he began at the Royal High School of Edinburgh. He was now well able to walk and explore the city as well as the surrounding countryside. His reading included chivalric romances, poems, history and travel books. He was given private tuition by James Mitchell in arithmetic and writing, and learned from him the history of the Kirk with emphasis on the Covenanters. After finishing school he was sent to stay for six months with his aunt Jenny in Kelso, attending the local Grammar School where he met James Ballantyne who later became his business partner and printed his books.[2]

Scott's meeting with Blacklock and Burns

Scott began studying classics at the University of Edinburgh in November 1783, at the age of only twelve, so he was a year or so younger than most of his fellow students. In March 1786 he began an apprenticeship in his father's office, to become a Writer to the Signet. While at the university Scott had become a friend of Adam Ferguson, the son of Professor Adam Ferguson who hosted literary salons. Scott met the blind poet Thomas Blacklock who lent him books as well as introducing him to James Macpherson's Ossian cycle of poems. During the winter of 1786–87 the fifteen year old Scott saw Robert Burns at one of these salons, for what was to be their only meeting. When Burns noticed a print illustrating the poem "The Justice of the Peace" and asked who had written the poem, only Scott could tell him it was by John Langhorne, and was thanked by Burns.[3] When it was decided that he would become a lawyer he returned to the university to study law, first taking classes in Moral Philosophy and Universal History in 1789–90.[2]

After completing his studies in law, he became a lawyer in Edinburgh. As a lawyer's clerk he made his first visit to the Scottish Highlands directing an eviction. He was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1792. He had an unsuccessful love suit with Williamina Belsches of Fettercairn, who married Sir William Forbes, 6th Baronet.

Literary career launched

At the age of 25 he began dabbling in writing, translating works from German, his first publication being rhymed versions of ballads by Bürger in 1796. He then published a three-volume set of collected Scottish ballads, The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. This was the first sign of his interest in Scottish history from a literary standpoint.

Scott then became an ardent volunteer in the yeomanry and on one of his "raids" he met at Gilsland Spa Margaret Charlotte Charpentier (or Charpenter), daughter of Jean Charpentier of Lyon in France whom he married in 1797. They had five children. In 1799 he was appointed Sheriff-Deputy of the County of Selkirk, based in the Royal Burgh of Selkirk.

In his earlier married days, Scott had a decent living from his earnings at the law, his salary as Sheriff-Deputy, his wife's income, some revenue from his writing, and his share of his father's rather meagre estate.

After Scott had founded a printing press, his poetry, beginning with The Lay of the Last Minstrel in 1805, brought him fame. He published a number of other poems over the next ten years, including the popular The Lady of the Lake, printed in 1810 and set in the Trossachs. Portions of the German translation of this work were later set to music by Franz Schubert. One of these songs, Ellens dritter Gesang, is popularly labelled as "Schubert's Ave Maria".

Another work from this period, Marmion, produced some of his most quoted (and most often mis-attributed) lines. Canto VI. Stanza 17 reads:

- Yet Clare's sharp questions must I shun,

- Must separate Constance from the nun

- Oh! what a tangled web we weave

- When first we practice to deceive!

- A Palmer too! No wonder why

- I felt rebuked beneath his eye;

In 1809 his sympathies led him to become a co-founder of the Quarterly Review, a review journal to which he made several anonymous contributions.

Novels

When the press became embroiled in pecuniary difficulties, Scott set out, in 1814, to write a cash-cow. The result was Waverley, a novel which did not name its author. It was a tale of the "Forty-Five" Jacobite rising in the Kingdom of Great Britain with its English protagonist Edward Waverley, by his Tory upbringing sympathetic to Jacobitism, becoming enmeshed in events but eventually choosing Hanoverian respectability. The novel met with considerable success. There followed a succession of novels over the next five years, each with a Scottish historical setting. Mindful of his reputation as a poet, he maintained the anonymous habit he had begun with Waverley, always publishing the novels under the name Author of Waverley or attributed as "Tales of..." with no author. Even when it was clear that there would be no harm in coming out into the open he maintained the façade, apparently out of a sense of fun. During this time the nickname The Wizard of the North was popularly applied to the mysterious best-selling writer. His identity as the author of the novels was widely rumoured, and in 1815 Scott was given the honour of dining with George, Prince Regent, who wanted to meet "the author of Waverley".

In 1819 he broke away from writing about Scotland with Ivanhoe, a historical romance set in 12th-century England. It too was a runaway success and, as he did with his first novel, he wrote several books along the same lines. Among other things, the book is noteworthy for having a very sympathetic Jewish major character, Rebecca, considered by many critics to be the book's real heroine — relevant to the fact that the book was published at a time when the struggle for the Emancipation of the Jews in England was gathering momentum.

As his fame grew during this phase of his career, he was granted the title of baronet, becoming Sir Walter Scott. At this time he organized the visit of King George IV to Scotland, and when the King visited Edinburgh in 1822 the spectacular pageantry Scott had concocted to portray George as a rather tubby reincarnation of Bonnie Prince Charlie made tartans and kilts fashionable and turned them into symbols of Scottish national identity.

Scott included little in the way of punctuation in his drafts which he left to the printers to supply.[4]

Financial woes

Beginning in 1825 he went into dire financial straits again, as his company nearly collapsed. That he was the author of his novels became general knowledge at this time as well. Rather than declare bankruptcy he placed his home, Abbotsford House, and income into a trust belonging to his creditors, and proceeded to write his way out of debt. He kept up his prodigious output of fiction (as well as producing a biography of Napoléon Bonaparte) until 1831. By then his health was failing, and he died at Abbotsford in 1832. Though not in the clear by then, his novels continued to sell, and he made good his debts from beyond the grave. He was buried in Dryburgh Abbey where nearby, fittingly, a large statue can be found of William Wallace—one of Scotland's most romantic historical figures.

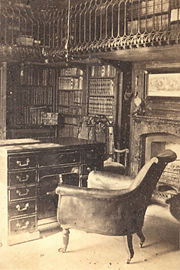

His home, Abbotsford House

When Sir Walter Scott was a boy he sometimes travelled with his father from Selkirk to Melrose, in the Border Country where some of his novels are set. At a certain spot the old gentleman would stop the carriage and take his son to a stone on the site of the battle of Melrose (1526). Not far away was a little farm called Cartleyhole, and this he eventually purchased. In due course the farmhouse developed into a wonderful home that has been likened to a fairy palace. Through windows enriched with the insignia of heraldry the sun shone on suits of armour, trophies of the chase, fine furniture, and still finer pictures. Panelling of oak and cedar and carved ceilings relieved by coats of arms in their correct colour added to the beauty of the house. More land was purchased, until Scott owned nearly 1,000 acres (4 km²), and it is estimated that the building cost him over £25,000. A neighbouring Roman road with a ford used in olden days by the abbots of Melrose suggested the name of Abbotsford.

The last of his direct descendants to inhabit Abbotsford House was his great-great-great granddaughter Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott (8 June 1923 - 7 July 2004). She inherited it from her elder sister Patricia in 1998. Patricia and Jean turned the house into one of Scotland's premier tourist attractions, after they had to rely on paying visitors to afford the upkeep of the house. It had electricity installed only in 1962. Dame Jean was at one time a lady-in-waiting to Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester; patron of the Dandie Dinmont Club, for a breed of dog named after one of Sir Walter Scott's characters; and a horse trainer, one of whose horses, Sir Wattie, ridden by Ian Stark, won two silver medals at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea.[5]

Critical assessment

Alternative View

Among the early critics of Scott was Mark Twain, who blamed Scott's "romanticization of battle" for what he saw as the South's decision to fight the American Civil War. Twain's ridiculing of chivalry in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, in which Twain has the main character repeatedly utter "great Scott" as an oath, is considered as specifically targeting Scott's books. Twain also targeted Scott in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn where he names a sinking boat the Walter Scott. Three crooks drown on this wreck.

From being one of the most popular novelists of the 19th century, Scott suffered from a disastrous decline in popularity after the First World War. The tone was set early on in E.M. Forster's classic "Aspects of the Novel" (1927), where Scott was savaged as being a clumsy writer who wrote slapdash, badly plotted novels. Scott also suffered from the rising star of Jane Austen. Considered merely an entertaining "woman's novelist" in the 19th century, in the 20th Austen began to be seen as perhaps the major English novelist of the first few decades of the 19th century. As Austen's star rose, Scott's sank, although, ironically, he had been one of the few male writers of his time to recognize Austen's genius.

Scott's ponderousness and prolixity were fundamentally out of step with Modernist sensibilities. Nevertheless, Scott was responsible for two major trends that carry on to this day. First, he essentially invented the modern historical novel; an enormous number of imitators (and imitators of imitators) would appear in the 19th century. It is a measure of Scott's influence that Edinburgh's central railway station, opened in 1854 for the North British Railway, is called Waverley Station. Second, his Scottish novels followed on from James Macpherson's Ossian cycle in rehabilitating the public perception of Highland culture after years in the shadows following southern distrust of hill bandits and the Jacobite rebellions. As enthusiastic chairman of the Celtic Society of Edinburgh he contributed to the reinvention of Scottish culture. It is worth noting, however, that Scott was a Lowland Scot, and that his re-creations of the Highlands were more than a little fanciful. His organisation of the visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822 was a pivotal event, leading Edinburgh tailors to invent many "clan tartans" out of whole cloth, so to speak. After being essentially unstudied for many decades, a small revival of interest in Scott's work began in the 1970s and 1980s. Ironically, postmodern tastes (which favoured discontinuous narratives, and the introduction of the 'first person' into works of fiction) were more favourable to Scott's work than Modernist tastes. Despite all the flaws, Scott is now seen as an important innovator, and a key figure in the development of Scottish and world literature.

Many of his works were illustrated by his friend, William Allan.

Memorials and commemoration

In addition to Landseer, fine portraits of him were painted by fellow-Scots Sir Henry Raeburn and James Eckford Lauder.

Sir Walter Scott is commemorated in Makars' Court, outside The Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh.

Selections for Makars' Court are made by The Writers' Museum; The Saltire Society; The Scottish Poetry Library.

Appearance on banknotes

Scott has been credited with rescuing the Scottish banknote. In 1826, there was outrage in Scotland at the attempt of the United Kingdom Parliament to prevent the production of banknotes of less than five pounds face value. Sir Walter Scott wrote a series of letters to the Edinburgh Weekly Journal under the pseudonym "Malachi Malagrowther" for retaining the right of Scottish banks to issue their own banknotes. This provoked such a response that the government was forced to relent and allow the Scottish banks to continue printing £1 notes. This campaign is commemorated to this day by his continued appearance on the front of all notes issued by the Bank of Scotland. The image on the 2007 series of banknotes is based on the portrait of Scott painted by Henry Raeburn.[6]

Works

The Waverley Novels

- Waverley (1814)

- Guy Mannering (1815)

- The Antiquary (1816)

- Rob Roy (1817)

- Ivanhoe (1819)

- Kenilworth (1821)

- The Pirate (1822)

- The Fortunes of Nigel (1822)

- Peveril of the Peak (1822)

- Quentin Durward (1823)

- St. Ronan's Well (1824)

- Redgauntlet (1824)

- Tales of the Crusaders, consisting of The Betrothed and The Talisman (1825)

- Woodstock (1826)

- Chronicles of the Canongate, 2nd series, The Fair Maid of Perth (1828)

- Anne of Geierstein (1829)

Tales of My Landlord

- 1st series The Black Dwarf and Old Mortality (1816)

- 2nd series, The Heart of Midlothian (1818)

- 3rd series, The Bride of Lammermoor and A Legend of Montrose (1819)

- 4th series, Count Robert of Paris and Castle Dangerous (1832)

Tales from Benedictine Sources

- The Abbot (1820)

- The Monastery (1820)

Short stories

- Chronicles of the Canongate, 1st series (1827). Collection of three short stories:

The Highland Widow, The Two Drovers and The Surgeon's Daughter.

- The Keepsake Stories (1828). Collection of three short stories:

My Aunt Margaret's Mirror, The Tapestried Chamber and Death Of The Laird's Jock.

Poems

- William and Helen, Two Ballads from the German (translator) (1796)

- The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802-1803)

- The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805)

- Ballads and Lyrical Pieces (1806)

- Marmion (1808)

- The Lady of the Lake (1810)

- The Vision of Don Roderick (1811)

- The Bridal of Triermain (1813)

- Rokeby (1813)

- The Field of Waterloo (1815)

- The Lord of the Isles (1815)

- Harold the Dauntless (1817)

- Young Lochinvar

- Bonnie Dundee (1830)

- patriotism

Other

- Introductory Essay to The Border Antiquities of England and Scotland (1814-1817)

- The Chase (translator) (1796)

- Goetz of Berlichingen (translator) (1799)

- Paul's Letters to his Kinsfolk (1816)

- Provincial Antiquities of Scotland (1819-1826)

- Lives of the Novelists (1821-1824)

- Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and Drama Supplement to the 1815–24 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Halidon Hill (1822)

- The Letters of Malachi Malagrowther (1826)

- The Life of Napoleon Buonaparte (1827)

- Religious Discourses (1828)

- Tales of a Grandfather, 1st series (1828)

- History of Scotland, 2 vols. (1829-1830)

- Tales of a Grandfather, 2nd series (1829)

- The Doom of Devorgoil (1830)

- Essays on Ballad Poetry (1830)

- Tales of a Grandfather, 3rd series (1830)

- Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft (1831)

- The Bishop of Tyre

Quote

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land!

from The Lay of the Last Minstrel by Walter Scott

Further reading

- Bautz, Annika. Reception of Jane Austen and Walter Scott: A Comparative Longitudinal Study. Continuum, 2007. ISBN-10 082649546X, ISBN-13 978-0826495464

- Brown, David. Walter Scott and the Historical Imagination. Routledge, 1979. ISBN 0710003013

References

- ↑ Sandyknowe and Early Childhood

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 School and University

- ↑ Literary Beginnings

- ↑ Stuart Kelly quoted by Arnold Zwicky in The Book of Lost Books at Language Log

- ↑ Obituary of Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 July 2004, p. 32

- ↑ "Bank of Scotland to launch new series of banknotes". Bank of Scotland press releases. HBOS plc (2007-06-21). Retrieved on 2008-10-14.

- Sir Walter Scott, John Buchan, Coward-McCann Inc., New York, 1932

See also

- Jedediah Cleishbotham (fictional editor of Tales of My Landlord, and Scott's alter ego)

- Alexandre Dumas, père

- Karl May

- Baroness Orczy

- Rafael Sabatini

- Emilio Salgari

- Samuel Shellabarger

- Lawrence Schoonover

- Jules Verne

- Frank Yerby

- GWR Waverley Class steam locomotives

External links

- Walter Scott Digital Archive at the University of Edinburgh library: includes much primary material

- The Edinburgh Sir Walter Scott Club

- Sir Walter Scott, biography by Richard H. Hutton, 1878, from Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Walter Scott at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Works by Walter Scott at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- University of Pennsylvania e-texts of some of Walter Scott's works

- Sir Walter Scott's death mask

- Dandie Dinmont Terriers named after a character in Guy Mannering

- The Keepsake Stories at Arthur's Classic Novels website.

- My Native Land audio - Bullwinkle voice impression

- Works by or about Walter Scott in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Scott, Walter |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Novelist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 15 August 1771 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Old Town, Edinburgh |

| DATE OF DEATH | 21 September 1832 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Abbotsford House, Scotland |