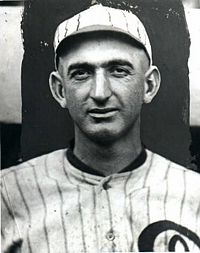

Shoeless Joe Jackson

| Shoeless Joe Jackson | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Outfielder | ||

| Born: July 16, 1888 Pickens County, South Carolina |

||

| Died: December 5, 1951 (aged 63) Greenville, South Carolina |

||

| Batted: Left | Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | ||

| August 25, 1908 for the Philadelphia Athletics |

||

| Final game | ||

| September 27, 1920 for the Chicago White Sox |

||

| Career statistics | ||

| Batting average | .356 | |

| Hits | 1,772 | |

| Run batted in | 785 | |

| Teams | ||

|

||

| Career highlights and awards | ||

|

||

Joseph Jefferson Jackson (July 16, 1888 – December 5, 1951), nicknamed "Shoeless Joe", was an American baseball player who played Major League Baseball in the early part of the 20th century. He is remembered for his performance on the field and for his association with the Black Sox Scandal, when members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox participated in a conspiracy to fix the World Series. As a result of Jackson's association with the scandal, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Major League Baseball's first commissioner, banned Jackson from playing after the 1920 season.[1]

Jackson played for three different Major League teams during his twelve-year career. He spent 1908-09 as a member of the Philadelphia Athletics; 1910 through the first part of the 1915 with the Cleveland Naps/Indians;[2] and the remainder of the 1915 season through 1920 with the Chicago White Sox.

Jackson, who played left field for most of his career, currently has the third highest career batting average. With his career having been cut short, the usual decline of a batter's hitting skills toward the end of a career did not have a chance to occur. In 1911, Jackson hit for a .408 average. That average is still the sixth highest single-season total since 1901, which marked the beginning of the modern era for the sport. His average that year set the record for highest batting average in a single season by a rookie.[3] Babe Ruth claimed that he modeled his hitting technique after Jackson's.[4]

Jackson still holds the White Sox franchise records for triples in a season and career batting average.[5] In 1999, he ranked Number 35 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players and was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

Jackson ranks 33rd on the all-time list for non-pitchers according to the win shares formula developed by Bill James.

Contents |

Early life

Joe Jackson was born in Pickens County, South Carolina. As a young child, Jackson worked in a textile mill in nearby Brandon Mill. Jackson's job prevented him from devoting any significant time to formal education.[6] His lack of education would be an issue throughout Jackson's life. It would become a factor during the Black Sox Scandal and has even affected the value of his collectibles. Because Jackson was uneducated, he often had his wife sign his signature. Consequently, anything actually autographed by Jackson himself brings a premium when sold.[7] In 1900, at the age of 13, Jackson started to play for the Brandon Mill baseball team.[8]

Jackson gets a nickname

According to Jackson, he got his nickname during a game against the Brandon Mill team. Jackson suffered from a blister on his foot from a new pair of cleats. They hurt so much that he had to take his shoes off before an at bat. Once he was on base, a fan started yelling inappropriate and vulgar comments at him. One of the things Jackson was called was a "Shoeless son of a gun." The name stuck with him throughout the remainder of his life.[9]

Professional career

Early professional career

1908 was an eventful year for Joe Jackson. Jackson began his professional baseball career when he joined the Greenville Spinners of the Carolina Association. He married Katie Wynn and eventually signed with Connie Mack to play Major League baseball for the Philadelphia Athletics.[9]"Chicago Historical Society". chicagohs.com. Retrieved on 2006-12-11.</ref> For the first two-years of his career, Jackson had some trouble adjusting to life with the Athletics. Consequently, he spent a portion of that time in the minor leagues. Between 1908 and 1909, Jackson appeared in ten games.[10] During the 1909 season, Jackson played 118 games for the South Atlantic League team in Savannah, Georgia. He batted .358 for the year.

Major League career

The Athletics finally gave up on Jackson in 1910 and traded him to the Cleveland Naps. After spending time with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association, he was called up to play on the big league team. He appeared in 20 games for the Naps that year and hit .387. In 1911, Jackson's first full-season, he set a number of rookie records. His .408 batting average that season is a record that still stands. The following season, Jackson batted .395 and led the American League in triples. The next year Jackson led the league with 197 hits and .551 slugging average.

In August of 1915 Jackson was traded to the Chicago White Sox. Two years later, Jackson and the White Sox won the World Series. During the series, Jackson batted .307 as the White Sox defeated the New York Giants.

In 1919, Jackson batted .351 during the regular season and .375 with perfect fielding in the World Series. The heavily favored White Sox lost the series to the Cincinnati Reds though. During the next year, Jackson batted .385 and was leading the American league in triples when he was suspended, along with seven other members of the White Sox, after allegations surfaced that the team had thrown the previous World Series.

Black Sox scandal

After the White Sox unexpectedly lost the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, eight players, including Jackson, were accused of throwing the Series to the Reds. In September 1920, a grand jury was convened to investigate.

During the Series, Jackson had 12 hits and a .375 batting average—in both cases leading both teams. He committed no errors, and even threw out a runner at the plate.[11] Jackson did bat far worse in the five games that the White Sox lost, hitting .286, with no RBI until the final contest, Game 8, when he hit a home run in the 3rd inning and added two more RBI on a double in the 8th, when the White Sox were way behind.

The Cincinnati Reds also hit an unusually high number of triples to left field during the series, far exceeding the amount that Jackson—generally considered a strong defensive player—normally allowed.[12]

In testimony before the grand jury, Jackson admitted under oath that he agreed to participate in the fix. He also admitted to complaining to other conspirators that he had not received his full $20,000 share. Legend has it that as Jackson was leaving the courthouse during the trial, a young boy begged of him, "Say it ain't so, Joe," and that Joe did not respond. In his 1949 interview in Sport Magazine, Jackson debunked this story as a myth.[13]

In 1921, a Chicago jury acquitted him and his seven White Sox teammates of wrongdoing. Nevertheless, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the newly appointed Commissioner of Baseball, banned all eight accused players, claiming baseball's need to clean up its image took precedence over legal judgments. As a result, Jackson never played major league baseball after the 1920 season.

Aftermath

During the remaining twenty years of his baseball career, Jackson played and managed with a number of minor league teams, most located in Georgia and South Carolina.[14] In 1922, Jackson returned to Savannah and opened a dry cleaning business.

In 1933, the Jacksons moved back to Greenville, South Carolina. After first opening a barbecue restaurant, Jackson and his wife opened "Joe Jackson's Liquor Store," which they operated until his death. One of the better known stories of Jackson's post-major league life took place at his liquor store. Ty Cobb and sportswriter Grantland Rice entered the store, with Jackson showing no sign of recognition towards Cobb. After making his purchase, the incredulous Cobb finally asked Jackson, "Don't you know me, Joe?" Jackson replied, "Sure, I know you, Ty, but I wasn't sure you wanted to know me. A lot of them don't."[15]

As he aged, Joe Jackson began to suffer from heart trouble. In 1951, at the age of 63, Jackson died of a heart attack.[8] He is buried at nearby Woodlawn Memorial Park.

Was Jackson innocent?

To this day, his name remains on the Major League Baseball Ineligible list. Jackson cannot be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame unless his name is removed from that list. However, he spent most of the last 30 years of his life proclaiming his innocence. In November 1999, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a motion to honor his sporting achievements, supporting a move to have the ban posthumously rescinded, so that he could be admitted to the Hall of Fame.[16] The motion was symbolic, as the U.S. Government has no jurisdiction in the matter. At the time, MLB commissioner Bud Selig confirmed that Jackson's case was under review, but to date, no action has been taken that would allow Jackson's admittance.

In recent years, evidence has come to light that casts doubt on Jackson's role in the fix. For instance, Jackson initially refused to take a payment of $5,000, only to have Lefty Williams toss it on the floor of his hotel room. Jackson then tried to tell White Sox owner Charles Comiskey about the fix, but Comiskey refused to meet with him. Also, before Jackson's grand jury testimony, team attorney Alfred Austrian coached Jackson's testimony in a manner that would be considered highly unethical even by the standards of the time, and would probably be considered criminal by today's standards. For instance, Austrian got Jackson to admit a role in the fix by pouring a large amount of whiskey down Jackson's throat. He also got the nearly illiterate Jackson to sign a waiver of immunity. Years later, the other seven players implicated in the scandal confirmed that Jackson was never at any of the meetings. Williams, for example, said that they only mentioned Jackson's name to give their plot more credibility.[11]

Career statistics

see: Baseball statistics for an explanation of these statistics.

| G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | R | RBI | BB | SO | AVG | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,332 | 4,981 | 1,772 | 307 | 168 | 54 | 873 | 785 | 519 | 158 | .356 | .423 | .517 |

Films and plays

- Eight Men Out, film directed by John Sayles, based on the Asinof book and starring D.B. Sweeney as Jackson

- Field of Dreams, film based on the Kinsella book, with Ray Liotta as Jackson

Jackson's nickname was also worked into the musical play Damn Yankees. The lead character, baseball phenomenon Joe Hardy, alleged to be from a small town in Missouri, is dubbed by the media as "Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, MO". The play also contains a plot element alleging that Joe had thrown baseball games in his earlier days.

Jackson was also an inspiration, in part, for the character Roy Hobbs in The Natural. Hobbs has a special name for his bat, and is offered a bribe to throw a game. In the book (but not the film) a youngster pleads with Hobbs, "Say it ain't so, Roy!"

See also

- Chicago White Sox all-time roster

- List of Major League Baseball doubles champions

- List of Major League Baseball triples champions

- List of Major League Baseball triples records

References

- ↑ "Joe Jackson FAQ". blackbetsy.com. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

- ↑ During Jackson's time with the franchise, Cleveland was known as the Naps during his years with them except for 1915

- ↑ Although he was in the majors as early as 1908, Major League rules at the time stipulated that a player was considered a rookie until he has had more than 130 at-bats in a season.[1]

- ↑ "The Baseball Page". thebaseballpage.com/players/jacksjo01.php. Retrieved on 2006-12-11.

- ↑ Listed at .340, his batting average while with the franchise.

- ↑ "Black Betsy Sale". shoelessjoejackson.com. Retrieved on 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "Signature Sale". jondube.com. Retrieved on 2007-01-01.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Joe Jackson Timeline". blackbetsy.com. Retrieved on 2006-11-26.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Chicago Historical Society". chicagohs.com. Retrieved on 2006-12-11.

- ↑ "JoeJackson.com Biography". shoelessjoejackson.com. Retrieved on 2006-12-11.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0761139435.

- ↑ Neyer, Rob. Say it ain't so ... for Joe and the Hall. ESPN Classic.com. 30 August 2007.

- ↑ Joe Jackson: This is the Truth

- ↑ "Joe Jackson Timeline". blackbetsy.com. Retrieved on 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "Ty Cobb & Joe Jackson story" (PDF). www.pde.state.pa.us. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

- ↑ "U.S. House Backs Shoeless Joe". CBS.com. Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

Bibliography

- "Shoeless: The Life And Times of Joe Jackson", by David L. Fleitz (2001, McFarland & Company Publishers)

- Shoeless Joe, a novel by W. P. Kinsella

- 8 Men Out, by Eliot Asinof

- Joe Jackson: A Biography, by Kelly Boyer Sagert

- Say It Ain't So, Joe!: The True Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson, by Donald Gropman

- A Man Called Shoeless, by Howard Burman

- "Burying the Black Sox" (Potomac, Spring 2006) by Gene Carney

- "Shoeless Joe & Me" (HarperCollins, 2002) by Dan Gutman

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube

- Shoeless Joe Jackson at Find A Grave

- hallyes.com Petition asking Bud Selig to reinstate Shoeless Joe

- shoelessjoejackson.com The Official Web Site

- See the letter written by Commissioner Landis banning Shoeless Joe Jackson from baseball

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||