Shetland

| Shetland Sealtainn |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Location | |||||

|

|||||

| Geography | |||||

| Area | Ranked 12th | ||||

| - Total | 1,466 km2 (566 sq mi) | ||||

| - % Water | ? | ||||

| Admin HQ | Lerwick | ||||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-ZET | ||||

| ONS code | 00RD | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Population | Ranked 31st | ||||

| - Total (2007) | 22,000 | ||||

| - Density | 15 /km² (39 /sq mi) | ||||

| Politics | |||||

| Shetland Islands Council http://www.shetland.gov.uk/ |

|||||

| Control | Independent | ||||

| MPs |

|

||||

| MSPs |

|

||||

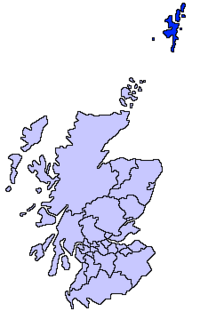

Shetland (formerly spelled Zetland, from Ȝetland; Old Norse Hjaltland; Scottish Gaelic: Sealtainn[1]) is an archipelago off the northeast coast of mainland Scotland. The islands lie to the northeast of Orkney, 280 km (170 mi) from the Faroe Islands and form part of the division between the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the North Sea to the east. The total area is approximately 1,466 km² (566 sq mi). Shetland constitutes one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. The islands' administrative centre and only burgh is Lerwick.

The largest island, known as "Mainland," has an area of 967 km² (374 sq mi), making it the third-largest Scottish island and the fifth-largest of the British Isles.

Shetland is also a lieutenancy area, comprises the Shetland constituency of the Scottish Parliament, and was formerly a county.

Contents |

History

Prehistory

Shetland has been populated since at least 3400 BC.[2] The early people subsisted on cattle-farming and agriculture. During the Bronze Age, around 2000 BC, the climate cooled and the population moved to the coast. During the Iron Age, many stone fortresses were erected, some ruins of which remain today. Around A.D. 297, Roman sources describe a people known as the Picts who ruled much of north Scotland, and Shetland eventually became part of the Pictish kingdom. Shetland's Picts were later conquered by the Vikings. Due to the practice, dating to at least the early Neolithic, of building in stone on the virtually tree-less islands, Shetland is extremely rich in physical remains of all these periods,[3] though fewer are preserved as Ancient Monuments than in Orkney.

The artefacts of all the eras of Shetland's past can be studied at the newly built (2007) Shetland Museum in Lerwick.

Norwegian colonisation

The image is from the Icelandic manuscript Flateyjarbók from the 1400s

By the end of the ninth century the Vikings shifted their attention from plundering to invasion, mainly due to the overpopulation of Norway in comparison to resources and arable land available there. Vikings colonised much of northern Europe, including Normandy, England, Scotland, Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, the Isle of Man, the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland, and subsequently North America. The Norwegians tended to follow a northern route to the islands and less populous places whereas the Danes went to more populated areas such as England and France, and the Swedes went east.[4]

Hjaltland was colonised by Norwegian Vikings in the 9th century, the fate of the existing indigenous population being uncertain. The colonisers gave it that name and established their laws and language. That language evolved into the West Nordic language Norn, which survived into the 1800s.

After Harald Hårfagre took control of all Norway, many of his opponents fled, some to Orkney and Shetland. From the Northern Isles they continued to raid Scotland and Norway, prompting Harald Hårfagre to raise a large fleet which he sailed to the islands. In about 875 he and his forces took control of Shetland and Orkney. Ragnvald, Earl of Møre received Orkney and Shetland as an earldom from the king as reparation for his son's being killed in battle in Scotland. Ragnvald gave the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.

Shetland was Christianised in the tenth century.

Conflict with Norway

In 1194 when king Sverre Sigurdsson (ca 1145 - 1202) ruled Norway and Harald Maddadsson was Earl of Orkney and Shetland, the Lendmann Hallkjell Jonsson and the Earl's brother-in-law Olav raised an army called the eyjarskeggjar on Orkney and sailed for Norway. Their pretender king was Olav's young foster son Sigurd, son of king Magnus Erlingsson. The eyjarskeggjar were beaten in the Battle of Florvåg near Bergen. The body of Sigurd Magnusson was displayed for the king in Bergen in order for him to be sure of the death of his enemy, but he also demanded that Harald Maddadsson (Harald jarl) answer for his part in the uprising. In 1195 the earl sailed to Norway to reconcile with King Sverre. As a punishment the king placed the earldom of Shetland under the direct rule of the king, from which it was probably never returned.

Increased Scottish interest

When Alexander III of Scotland turned twenty-one in 1262 and became of age he declared his intention of continuing the aggressive policy his father had begun towards the western and northern isles. This had been put on hold when his father had died thirteen years earlier. Alexander sent a formal demand to the Norwegian King Håkon Håkonsson.

After decades of civil war, Norway had achieved stability and grown to be a substantial nation with influence in Europe and the potential to be a powerful force in war. With this as a background, King Håkon rejected all demands from the Scots. The Norwegians regarded all the islands in the North Sea as part of the Norwegian realm. To add weight to his answer, King Håkon activated the leidang and set off from Norway in a fleet which is said to have been the largest ever assembled in Norway. The fleet met up in Breideyarsund in Shetland (probably today's Bressay Sound) before the king and his men sailed for Scotland and made landfall on Arran. The aim was to conduct negotiations with the army as a backup.

Alexander III drew out the negotiations while he patiently waited for the autumn storms to set in. Finally, after tiresome diplomatic talks, King Håkon lost his patience and decided to attack. At the same time a large storm set in which destroyed several of his ships and kept others from making landfall. The Battle of Largs in October 1263 was not decisive and both parties claimed victory, but King Håkon Håkonsson's position was hopeless. On 5 October, he returned to Orkney with a discontented army, and there he died of a fever on 17 December 1263. His death halted any further Norwegian expansion in Scotland.

King Magnus Lagabøte broke with his father's expansion policy and started negotiations with Alexander III. In the Treaty of Perth of 1266 he surrendered his furthest Norwegian possessions including Man and the Sudreyar (Hebrides) to Scotland in return for 4,000 marks sterling and an annuity of 100 marks. The Scots also recognised Norwegian sovereignty over Orkney and Shetland.

One of the main reasons behind the Norwegian desire for peace with Scotland was that trade with England was suffering from the constant state of war. In the new trade agreement between England and Norway in 1223 the English demanded Norway make peace with Scotland. In 1269, this agreement was expanded to include mutual free trade.

Pawned to Scotland

In the 14th century Norway still treated Orkney and Shetland as a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing, and in 1379 the Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson.[5] In 1348 Norway was severely weakened by the Black Plague and in 1397 it entered the Kalmar Union. With time Norway came increasingly under Danish control. King Christian I of Denmark and Norway was in financial trouble and, when his daughter Margaret became engaged to James III of Scotland in 1468, he needed money to pay her dowry. Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Riksråd (Council of the Realm) he entered into a contract on 8 September 1468 with the King of Scotland in which he pawned Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilders.[6] On 28 May the next year he also pawned Shetland for 8,000 Rhenish guilders.[7] He secured a clause in the contract which gave future kings of Norway the right to redeem the islands for a fixed sum of 210 kilograms (460 lb) of gold or 2,310 kilograms (5,100 lb) of silver. Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success.[8]

Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by an Act of Parliament on 27 December 1669 which officially made the islands a Crown dependency and exempt from any "dissolution of His Majesty’s lands". In 1742 a further Act of Parliament returned the estates to a later Earl of Morton, although the original Act of Parliament specifically ruled that any future act regarding the islands status would be "considered null, void and of no effect".

The Hansa era

After the decline of the Vikings, four centuries followed where the Shetlanders sold their goods through the Hanseatic League of German merchantmen in Bergen, and later to merchants from Bremen, Lübeck and Hamburg. The Hansa would buy shiploads of salted cod and ling. In return, the island population received cash, grain, cloth, beer and other goods. The trade with the North German towns lasted until the 1707 Act of Union prohibited the German merchants from trading with Shetland. Shetland then went into an economic depression as the Scottish and local traders were not as skilled in trading with salted fish. However, some local merchant-lairds took up where the German merchants had left off, and fitted out their own ships to export fish from Shetland to the Continent. For the independent farmers of Shetland this had negative consequences, as they now had to fish for these merchant-lairds.[9] With the passing of the Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886 the Liberal prime minister William Ewart Gladstone emancipated crofters from the rule of the landlords. The Act enabled those who had effectively been landowners' serfs to become owner-occupiers of their own small farms.[10][11]

Napoleonic wars

Some 3000 Shetlanders served in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars from 1800 to 1815.[12]

World War II

During World War II a Norwegian naval unit nicknamed the "Shetland Gang" was established by the Special Operations Executive Norwegian Section in the autumn of 1940 with a base first at Lunna and later in Scalloway in order to conduct operations on the coast of Norway. About 30 fishing vessels used by Norwegian refugees were gathered in Shetland. Many of these vessels were rented, and Norwegian fishermen were recruited as volunteers to operate them.

The Shetland Gang sailed in covert operations between Norway and Shetland, carrying men from Company Linge, intelligence agents, refugees, instructors for the resistance, and military supplies. Many people on the run from the Germans, and much important information on German activity in Norway, were brought back to the Allies this way. Some mines were laid and direct action against German ships was also taken. At the start the unit was under a British command, but later Norwegians joined in the command.

The fishing vessels made 80 trips across the sea. German attacks and bad weather caused the loss of 10 boats, 44 crewmen, and 60 refugees. Because of the high losses it was decided to procure faster vessels. The Americans gave the unit the use of three submarine chasers (HNoMS Hessa, HNoMS Hitra and HNoMS Vigra). None of the trips with these vessels incurred loss of life or equipment.[13]

The Shetland Gang made over 200 trips across the sea and the most famous of the men, Leif Andreas Larsen (Shetlands-Larsen) made 52 of them.[14]

Shetland today

In the early 1970s, oil and gas were found off Shetland. The East Shetland Basin is one of the largest petroleum sedimentary basins in Europe and the oil extracted there is sent to the terminal at Sullom Voe (Norse: Solheimavagr). Sullom Voe terminal opened in 1978 and is the largest oil export harbour in the United Kingdom with a volume of 25 million tons per year.

Income from oil, and the improved economic state that oil-related development has brought, has resulted in reduced emigration and vastly improved infrastructure throughout Shetland, leading to an improved quality of life.

As a result of the oil revenue and the cultural links with Norway, a small independence movement developed briefly within Shetland. It saw as its model the Isle of Man, as well as its closest neighbour, Faroe, an autonomous dependency of Denmark.[15]

Sheep farming also plays a big part in Shetland today. Fishing is also important, but not as much as it used to be.

Timeline

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 3400 BC | First sign of settlement |

| 297 AD | Roman sources mention the Picts |

| 43 & 77 AD | Roman authors Pomponius Mela and Pliny the Elder refers to the seven islands they call Haemodae and Acmodae respectively, assumed to be Shetland.[16] |

| 875 | Harald Hårfagre took control of the islands |

| 1195 | Harald Maddadsson lost the earldom of Shetland and the islands are put directly under the Norwegian king Sverre Sigurdsson |

| 1379 | The Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson |

| 1469 | Christian I pawned Shetland to the Scottish king James III |

| 1700-1760 | Smallpox hit the islands hard |

| 1700s | Norn language gradually dies out |

| 1707 | The German merchants lost their trading rights in Shetland |

| 1708 | Capital moved from Scalloway to Lerwick |

| 1861 | 32,000 inhabitants |

| 1880s | William Ewart Gladstone freed the serfs |

| 1940 | Shetland bus established by the Special Operations Executive |

| 1961 | 17,814 inhabitants |

| 1969 | Shetland marks 500 years under both Norwegian and Scottish rule |

| 1975 | Lerwick Town Council and Zetland County Council merged to Shetland Islands Council |

| 1978 | Oil terminal in Sullom Voe opened |

| 2001 | 21,990 inhabitants |

| 2005 | Lord Lyon King of Arms, the heraldic authority of Scotland, approved the blue and white flag of Shetland as an official flag |

Culture

The main cultural influences on Shetland are Scandinavian (especially Norwegian) and British (especially Scottish) but North Sea and North Atlantic commerce have ensured various other influences. Shetland's fiddle music is a blend of ancient Norwegian folk music, Scots reels, jigs and slow airs, and tunes brought home by sailors from Ireland, Germany, North America and even Greenland. Notable exponents of Shetland folk music include fiddle players, the late Tom Anderson and Aly Bain, and the guitarist, the late Peerie Willie Johnson.

The landscape and the light found in Shetland have been an inspiration to many artists in the fields of painting, drawing and sculpturing, both local and from elsewhere. There are several local art galleries. As with other Scottish dialects, the Shetland dialect, a mixture of old English, Scots and Norse words, was actively discouraged in schools, churches and civic life until the late twentieth century, but has since then been restored as a language of culture. It is used both in local radio and dialect writing, and kept alive by the Shetland Folk Society and the quarterly New Shetlander magazine.[17]

Up Helly Aa is one of a variety of fire festivals held in Shetland annually in the middle of winter. The festival is just over 100 years old in its present, highly organised form. Originally a temperance festival held to break up the long nights of winter the festival has become one celebrating the isles heritage and includes a procession of men dressed as Vikings, the burning of a replica longship and copious amounts of alcohol. The main Up Helly Aa in Lerwick bars women from taking part in the processions of guizers. Instead, women prepare food for the big night.[18]

Shetland competes in the bi-annual Island Games, which it hosted in 2005.

Language

The Pictish language died out during the Viking occupation to be replaced by Old Norse, which in turn evolved into Norn. This remains the most prominent remnant of Norse culture on the islands. Almost every place name in use there can be traced back to the Vikings.[19] Norn continued to be spoken until the 18th century when it was replaced by an insular dialect of Scots also known as Shetlandic, which in turn is being replaced by Scottish English.

Although Norn was spoken for hundreds of years it is now extinct and few written sources remain.

Example of the Lord's Prayer in Shetland Norn:

|

Shetland Norn

|

Translation to modern Norwegian (nynorsk)

|

Old Norse version

|

|

English version (not literal translation)

Jakob Jakobsen was a Faroese linguist and leading documentarist of Norn

|

For a comparison with Orkney Norn and other languages please see: The Lord's Prayer in different languages.

Name

The original Norse name for Shetland was Hjaltland. Hjalt in Old Norse meaning the hilt or crossguard of a sword. As with all western dialects of Norse, the stressed 'a' shifts to 'e' and so the ja became je as with Norse hjalpa which became hjelpa. Then the pronunciation of the combination of the letters hj changed to sh. This is also found in some Norwegian dialects in for instance the word hjå (with) and the place names Hjerkinn and Sjoa (from *Hjó). Lastly the l before the t disappeared.[20].

As Norn was gradually replaced by Scots Shetland became Ȝetland (the initial letter being the Middle Scots letter, yogh (which can also be found in the name Menzies). This sounded almost identical to the original Norn sound, /hj/). When the letter yogh was discontinued, it was often replaced by the similar-looking letter 'z', hence Zetland, the mispronounced form used to describe the pre-1975 county council.

Norse names

The old Norse names of the principal islands were:

- Hjaltland (Mainland)

- Jell (Yell) - might be pre-Norse Pictish

- Unst - might be pre-Norse Pictish

- Fetlar - might be pre-Norse Pictish

- Hvalsey (Whalsay) - literally whale island (Hvalsøy/Kvalsøy in modern Norwegian)

- Brusey (Bressay) - most likely named after a Norse nobleman Bruse

- Fugley (Foula) - literally bird's island (Fugløy in modern Norwegian)

- Frjóey (Fair Isle) - literally fertile island (Froøy/Fræøy in modern Norwegian)

Shetland on film

Michael Powell made The Edge of the World in 1937. This film is a dramatisation based on the true story of the evacuation of the last 36 inhabitants of the remote island of St Kilda on 29 August 1930. St Kilda lies in the Atlantic Ocean, 64 kilometres west-northwest of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides; the inhabitants spoke Gaelic. Powell was unable to get permission to film on St. Kilda. Undaunted, he made the film over four months during the summer of 1936 on the island of Foula, in the Shetland Isles. The film transposes these events to one of the islands of Shetland. 40 years later, the documentary Return To The Edge Of The World (1978) was filmed, capturing a reunion of cast and crew of the film as they visited the island.

A number of other films have been made on or about Shetland:

- The Rugged Island: A Shetland Lyric (1934)[21]

- A Crofter's Life in Shetland (1932)[22]

- Devil's Gate (2003).

- It's Nice Up North (2006) comedy documentary by Graham Fellows as John Shuttleworth.

Shetland in literature

The first section of Raman Mundair's book A Choreographer's Cartography is "60 degrees north" - a series of poems, some in the Shetland dialect, that reflect the poet's experiences of Shetland and offers a unique British Asian perspective on the landscape.[23]

Hugh MacDiarmid, the Scots poet and writer lived in Whalsay from the mid-1930s through 1942, and wrote many poems there, including a number that directly address or reflect the Shetland environment (e.g. "On A Raised Beach").

Churches

There are churches of many different denominations in Shetland, with the largest variety found in Lerwick. Unlike much of Scotland, the Methodist Church has a relatively high membership in Shetland. Shetland comprises a District of the Methodist Church (the rest of Scotland comprises a separate District). The Church of Scotland has a Presbytery of Shetland; the largest church is Lerwick and Bressay Parish Church.[24]

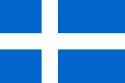

Flag

Roy Grönneberg founded the local chapter of the Scottish National Party in 1966 and was active in the struggle for Shetland autonomy. In 1969 he designed the flag of Shetland in cooperation with Bill Adams to mark the 500 year anniversary of the transfer of Shetland from Norway to Scotland.[25]

The reasons behind the design was the desire to illustrate the Shetland had been a part of Norway for 500 years and a part of Scotland for 500 years. The colours are identical to the ones in Flag of Scotland, but shaped in the Nordic cross and is the same design Icelandic republicans used in the early 20th century known in Iceland as Hvítbláinn, the white-blue.

In 1975 when the new Shetland Islands Council came into being Grönneberg wanted his proposed flag to become the official flag of Shetland, but was unsuccessful. A plebiscite in 1985 also failed to give it official status. Finally, in 2005 the Lord Lyon King of Arms approved the flag as the official flag of Shetland.

Geography

- See also: List of Shetland islands

Out of the approximately 100 islands, only 15 are inhabited. The main island of the group is known as Mainland. The other inhabited islands are: Bressay, Burra, Fetlar, Muckle Roe, Papa Stour, Trondra, Vaila, Unst, Whalsay, Yell in the main Shetland group, plus Foula to the south-west, Fair Isle to the south, and Housay and Bruray in the Out Skerries to the east (see below).

Fair Isle lies approximately halfway between Shetland and Orkney, but it is administered as part of Shetland. The Out Skerries lie east of the main group. Due to the islands' latitude, on clear winter nights the aurora borealis or "northern lights" can sometimes be seen in the sky, while in summer there is almost perpetual daylight, a state of affairs known locally as the "simmer dim".

| County of Zetland until circa 1890 |

|

| Geography | |

| Area - Total |

Ranked 15th 352,876 acres (142,804 ha) |

|---|---|

| County town | Lerwick |

| Chapman code | SHI |

Climate

Shetland has a Maritime Subarctic climate. The climate all year round is mild due to the influence of the relative warmth of the surrounding seas, the surface temperature of which falls to 5 °C (41 °F) in early March and peaks at 13 to 14°C (55-57°F) in late August. However, summers are cool and temperatures over 21 °C (70 °F) are rare. The warmest month on record was August 1947, when the average maximum temperature was 17.2 °C (63.0 °F).

The general character of the climate is windy and cloudy with at least 1 mm (0.039 in) of rain falling on about 200 days a year. Average yearly precipitation at Lerwick is 1,238 mm (48.7 in), with November and December the wettest months, together receiving about a quarter of annual precipitation. Snowfall can occur at any time from July to early June although it seldom lies on the ground for more than a day. Less rain falls from April to August although no month receives less than 50 mm (2.0 in). Fog is common in the east of the islands during summer due to the cooling effect of the sea on mild southerly airflows.

There is a wide variation in day length during the course of the year due the islands' northerly location. On the shortest day at the winter solstice sunlight lasts 3 hours and 45 minutes and this stretches to 23 hours at the summer solstice, with twilight occupying the remainder of the time. However, the remoteness of the islands from warm and dry airflows means that all months are cloudy. Annual sunshine hours average 1065 hours so fine days are rare and overcast days are common.[26]

| Average maximum temperature coldest month | 4.9 °C (40.8 °F) (February) |

| Average maximum temperature warmest month | 14 °C (57 °F) (August) |

| Number of days with air frost | 33 days |

| Annual precipitation | 1,037 mm (40.8 in) |

| Number of days a year with snowfall | 60 days |

| Number of days a year with rain or showers | 285 days[27] |

Flora

The landscape in Shetland is marked by the grazing of sheep and the rarity of trees. The flora is dominated by Arctic-alpine plants, wild flowers, moss and lichen. Shetland Mouse-ear (Cerastium nigrescens) is an endemic plant found only in Shetland. It was first recorded in 1837 by botanist Thomas Edmondston. Although reported from two other sites in the 19th century, it currently grows only on two serpentine hills on the island of Unst.[28][29]

Fauna

Shetland is the site of one of the largest bird colonies in the North Atlantic, home to more than one million birds. Most birds are found in colonies on Hermaness, Foula, Mousa, Noss, Sumburgh Head and Fair Isle. Some of the birds found on the islands are Atlantic Puffin, Storm-petrel, Northern Lapwing and Winter Wren. Many arctic birds spend the winter on Shetland and among those are Whooper Swan and Great Northern Diver. The Shetland Isles are also the home of the Shetland Sheepdog or 'Sheltie' which is a small, robust and graceful dog.

The geographical isolation and recent glacial history of Shetland have resulted in a depleted mammalian fauna. The Wood Mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus L.), along with the Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus Berkenhout) and the House Mouse (Mus musculus domesticus), are the only recorded types of rodent present on the island. Based largely on morphological studies of epigenetic variations, the source of the original founding population has been attributed to Norway with the most obvious date of introduction being presumed to be around the 9th century AD with the arrival of the Vikings. However, archaeological evidence now suggests that this species was present during the Middle Iron Age (around 200 BC - AD 400), and one theory proposes that Apodemus was in fact introduced from Orkney where a population had existed since at the least the Bronze Age.[30]

Notable places

- Clickimin broch

- Fort Charlotte

- Jarlshof archaeological site

- Mavis Grind

- Mousa Broch

- Muness Castle the most northerly castle in the United Kingdom

- Old Scatness archaeological site

- Scalloway Castle

- Selivoe

- St Ninian's Isle

- Sullom Voe oil terminal

- Sumburgh Head

- Skaw the most northerly settlement in the United Kingdom

- The most northerly phone box in the United Kingdom

Subdivisions

Shetland is subdivided into 22 parishes or wards that no longer have administrative significance but are used for statistical purposes:

- Sound

- Clickimin

- North Central

- Breiwick

- South Central

- Harbour and Bressay

- North

- Upper Sound, Gulberwick and Quarff

- Unst and Island of Fetlar

- Yell

- Northmavine, Muckle Roe and Busta

- Delting West

- Delting East and Lunnasting

- Nesting, Whiteness, Girlsta and Gott

- Scalloway

- Whalsay/Skerries

- Sandsting, Aithsting and Weisdale

- Walls, Sandness and Clousta

- Burra/Trondra

- Cunningsburgh and Sandwick

- Sandwick, Levenwick and Bigton

- Dunrossness

Economy

Fishing has been an integral part of Shetland's economy since prehistory and it remains central to the islands' economy even today. It was also important in bringing in commerce from outside the isles, for example the 17th century Hanseatic traders and Victorian-era herring activities.

The main revenue producers in Shetland today are agriculture, aquaculture, fishing and the petroleum industry (crude oil and natural gas production). Farming is mostly concerned with the raising of Shetland sheep,[31] known for their unusually fine wool. Crops raised include oats and barley; however, the cold, windswept islands make for a harsh environment for most plants. Crofting, the farming of small plots of land on a legally restricted tenancy basis, is still practiced and viewed as a key Shetland tradition as well as important source of income. The Shetland Pony is another important aspect of the Shetland farming tradition.

More recently, oil reserves discovered in the 20th century out to sea have provided a much needed alternative source of income for the islands. The East Shetland Basin is one of Europe's largest oil fields. Oil produced there is landed at the Sullom Voe terminal in Shetland. Taxes from the oil have increased spending on social welfare, art, sport, environmental measures and financial development. Three quarters of the islands work force is employed in the service sector. Even though oil makes up 15% of the islands' economy, (£116 million a year), the fish-related industry generates twice as much income and employs three times as many workers.[32] The oil revenue allows increased expenditure by the Shetland Islands Council, which alone accounted for 27.9% of employment in 2003.[33]

For the last 25 years unemployment has been under 5% and as of 2004 was 2%, but the fluctuations in the market for farmed salmon and trawled white fish leads to seasonal changes in unemployment.

In January 2007, the Shetland Islands Council signed a partnership agreement with Scottish and Southern Energy for a 200 turbine wind farm and subsea cable. The renewable energy project would produce about 600 megawatts and contribute about £20 million to the Shetland economy per year.[34] The plan is meeting significant opposition within the islands, primarily resulting from the anticipated visual impact of the development.

Media

Shetland is served by a weekly local newspaper, The Shetland Times (one of the first UK newspapers to publish on the internet), two monthly magazines, Shetland Life and i'i' Shetland and a news website, www.shetland-news.co.uk.

Radio service is provided by BBC Radio Shetland (the local opt-out of BBC Radio Scotland) and SIBC, a commercial radio station.

Transport

Transport between islands is primarily by ferry. Shetland is served by a domestic ferry connection from Lerwick to the mainland, operated by Northlink Ferries to Aberdeen.

Sumburgh Airport, the main airport on Shetland, is located close to Sumburgh, 40 km (25 miles) south of Lerwick. Loganair operates flights for FlyBe to other parts of the British Isles seven times a day. The destinations are Kirkwall, Aberdeen, Inverness, Glasgow and Edinburgh. In the summer months, there are also flights to London Stansted and the Faeroes operated by the Faeroese airliner Atlantic Airways.

Inter-Island flights from the Shetland Mainland to Fair Isle, Foula, Papa Stour, and Out Skerries are operated from Tingwall Airport 11 km west of Lerwick, by Directflight Ltd., using Islander aircraft owned by the Shetland Islands Council.

There are frequent charter flights from Aberdeen to Scatsta (near Sullom Voe), which are used to transport oilfield workers.

Public services

The Shetland Islands Council provide services in the areas of Environmental Health , Roads, Social Work, Community Development, Organisational Development, Economic Development, Building Standards, Trading Standards, Housing, Waste, Education, Burial Grounds, Fire Service, Port and Harbours and others.

The political composition of the Council is 22 Independents.

In Shetland there are a total of 34 schools: two High Schools, seven Junior High Schools with primary and nursery departments, and 25 Primary Schools. The High Schools are Anderson High School and Brae High School. Shetland is also home to the North Atlantic Fisheries College.

The Shetland NHS is the local Scottish health service in the Shetland Islands.

People

It is believed that the island group had an original population about which little is known who were replaced or assimilated by the Picts. Historical, archaeological, place-name and linguistic evidence indicates Norse cultural dominance of Shetland during the Viking period.[35] A few place names might have Pictish origin, but this is disputed. Several genetic studies have been conducted investigating the genetic makeup of the islands' population today in order to establish its origin. Shetlanders are less than half Scandinavian in origin. They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives.[36] After the islands were transferred to Scotland thousands of Scots families emigrated to Shetland in the 16th and 17th centuries. Contacts with Germany and the Netherlands through the fishing trade brought smaller numbers of immigrants from those countries. World War II and the oil industry have also contributed to population increase through immigration.[37]

Population development

The population development on Shetland has through the times been affected by deaths at sea and epidemics. Smallpox afflicted the islands in the 17th and 18th centuries, but as vaccines became common after 1760 the population increased to 40,000 in 1861. The population increase led to a lack of food and many young men went away to serve in the British merchant fleet. 100 years later the islands' population was more than halved. This decrease was mainly caused by the large number of Shetlandic men being lost at sea during the two world wars and the waves of emigration in the 1920s and 1930s. Now more people of Shetlandic background live in Canada, Australia and New Zealand than in Shetland.

| District | Population 1961 | Population 1971 | Population 1981 | Population 1991 | Population 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bound Skerry (& Grunay) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bressay | 269 | 248 | 334 | 352 | 384 |

| Bruray | 34 | 35 | 33 | 27 | 26 |

| East Burra | 92 | 64 | 78 | 72 | 66 |

| Fair Isle | 64 | 65 | 58 | 67 | 69 |

| Fetlar | 127 | 88 | 101 | 90 | 86 |

| Foula | 54 | 33 | 39 | 40 | 31 |

| Housay | 71 | 63 | 49 | 58 | 50 |

| Mainland | 13,282 | 12,944 | 17,722 | 17,562 | 17,550 |

| Muckle Flugga | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muckle Roe | 103 | 94 | 99 | 115 | 104 |

| Noss | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Papa Stour | 55 | 24 | 33 | 33 | 25 |

| Trondra | 20 | 17 | 93 | 117 | 133 |

| Unst | 1,148 | 1,124 | 1,140 | 1,055 | 720 |

| Vaila | 9 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| West Burra | 561 | 501 | 767 | 817 | 753 |

| Whalsay | 764 | 870 | 1,031 | 1,041 | 1,034 |

| Yell | 1,155 | 1,143 | 1,191 | 1,075 | 957 |

| Total | 17,814 | 17,327 | 22,768 | 22,522 | 21,990 |

See also: List of Shetland islands

Notable Shetlanders

- Arthur Anderson (1792-1868), co-founder of P&O.

- Tom Anderson MBE (1910-1991), a fiddler, composer, folklorist and teacher who was a profoundly influential figure in the development of Shetland music.

- Aly Bain (b. 1946), fiddle player.

- Ian Bairnson (b. 1953), session guitarist for The Alan Parsons Project.

- Professor Stanley Bowie (1917-2008), world authority on uranium geology and a leader in the field of geochemistry and mineralogy.[38]

- Sir William Watson Cheyne of Leagarth (b. 14 December 1852, d. 19 April 1932). Pioneer in the development of antiseptic[39]

- Morgan Goodlad (b. 1950), controversial Chief Executive of Shetland Islands Council who was found guilty of maladministration by the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman on 23 May 2007.[40][41][42]

- Sir Herbert John Clifford Grierson (1866-1960), a literary scholar and critic.

- Neil Hughes from Seven Up!.

- Stuart Hill (b. 1943), eccentric campaigner for Shetland independence.

- Willie Hunter (1934-1994), player and composer of Shetland fiddle music.

- Robert Alan Jamieson (b. 1958), poet and novelist.

- Peerie Willie Johnson (1920-2007), a highly renowned pioneer of jazz swing influenced folk guitar who played with the likes of Tom Anderson and Willie Hunter.

- Norman Lamont (b. 1942), Conservative MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1990 to 1993.

- Christine De Luca, poet.

- Steven Robertson (b. 1980), a theatre and film actor from Vidlin.

- Robert Stout (1844-1930), Prime Minister of New Zealand on two occasions in the late 19th century.

- Hazel Tindall, world champion knitter.

- Astrid Williamson, musician.

- "Vagaland" (1903-1973), often considered the national poet.

- Sandra Voe (b. 1936), actress appearing in many small film and TV roles (including Coronation Street) and mother of Pulp keyboard player Candida Doyle.

References

- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 075242517X

- Fleming, Andrew (2005) St. Kilda and the Wider World: Tales of an Iconic Island. Windgather Press ISBN 1905119003

- Nicolson, James R. (1972) Shetland. Newton Abbott. David & Charles.

- Turner, Val (1998) Ancient Shetland. London. B. T. Batsford/Historic Scotland. ISBN 0713480009

Notes

- ↑ It should be noted that there is no evidence of Gaelic as a community language in Shetland

- ↑ The Scourd of Brouster site in Walls includes a cluster of six or seven walled fields and three stone circular houses that contains the earliest hoe-blades found so far in Scotland. See Fleming (2005) p. 47 quoting Clarke, P.A. (1995) Observations of Social Change in Prehistoric Orkney and Shetland based on a Study of the Types and Context of Coarse Stone Artefacts. M. Litt. thesis. University of Glasgow.

- ↑ Turner (1998) p. 18 states that there are over 5,000 archaeological sites all told.

- ↑ James Graham-Campbell: Cultural Atlas of the Viking World, 1999. Page 38. ISBN 0816030049

- ↑ Julian Richards, Vikingblod, page 235, Hermon Forlag, ISBN 8283200165

- ↑ Acquisition of Orkney and Shetland 1468-9

- ↑ University Library, University in Bergen: Article on Shetland (Norwegian)

- ↑ Universitas, Norsken som døde (Norwegian article on the history of the islands) (Norwegian)

- ↑ Visit Shetland history page

- ↑ "A History of Shetland" visitshetland.com. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ McLean, Duncan (20 September 1998) "Getting on the Map". London. The Independent. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Ursula Smith" Shetlopedia. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ University in Bergen, Historical institute page on the Shetland Gang(Norwegian)

- ↑ Kulturnett Hordaland page on Shetlands-Larsen(Norwegian)

- ↑ New Statesman - Independence thinking

- ↑ Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Ballin Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Visit Shetland page on culture

- ↑ Visit Shetland page on Up Helly Aa

- ↑ Julian Richards, Vikingblod, page 236, Hermon Forlag, ISBN 8283200165

- ↑ Norwegian language council: Placenames with -a, hjalt, Leirvik, vin in placenames(Norwegian)

- ↑ "The Rugged Island: A Shetland Lyric" IMDb. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ "A Crofter's Life in Shetland" screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Mundair, Raman (2007) A Choreographer's Cartography. Leeds. Peepal Tree Press. ISBN 9781845230517

- ↑ "Lerwick and Bressay Parish Church, St Columba's, " shetland-museum. Retrieved 12 October 2008. "It... is the largest church in Shetland... affectionately known as "the Big Kirk" ".

- ↑ Flags of the Worlds page on the flag of Shetland

- ↑ UK Meteorological Office, www.meto.gov.uk

- ↑ Shetlands tourist agency climate page. visitshetland.com. Retrieved 19 April 2007

- ↑ Scott, W. & Palmer, R. (1987) The Flowering Plants and Ferns of the Shetland Islands. Shetland Times. Lerwick.

- ↑ Scott, W. Harvey, P., Riddington, R. & Fisher, M. (2002) Rare Plants of Shetland. Shetland Amenity Trust. Lerwick.

- ↑ Nicholson, R.A., Barber, P., and Bond, J.M. (2005). New Evidence for the Date of Introduction of the House Mouse, Mus musculus domesticus Schwartz & Schwartz, and the Field Mouse, Apodemus sylvaticus (L.) to Shetland. Environmental Archaeology 10 (2): 143-151

- ↑ Shetland sheep

- ↑ Visit Shetland's economy page

- ↑ Shetland Islands Council. "Shetland In Statistics 2005".

- ↑ BBC News 'Powering on with Island wind plan', 19 Jan 2007

- ↑ Jones G. (1984) A History of the Vikings Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- ↑ Article: Genetic evidence for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods

- ↑ Visit Shetland page on the people

- ↑ [1] timesonline.co.uk Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ "Sir William Watson Cheyne" watson-cheyne.com. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Private Eye No 1144 p. 27

- ↑ "News From Around the Fish Farms, April 2004" The Salmon Farm Monitor. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ "Morgan's "maladministration" " The Shetland News Retrieved 12 October 2008.

External links

- Shetland travel guide from Wikitravel

- VisitShetland.com

- Shetland.org

- Up-Helly-Aa: Insideoot, a book by Vertigo

- Shetland in Statistics (pdf file)

- Shetland Dialect

- Shetlink - Shetland's Online Community

- Undiscovered Scotland - Shetland Islands

- Shetland Islands Council

- Shetland Scenes

- Virtual Tour of Shetland

- Shetlopedia.com - The Shetland Encyclopedia that anyone can edit

- Tom Weir on the Shetland Language

- ShetlandDictionary.com - Online Shetland Dictionary

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||