Scottish Gaelic

| Scottish Gaelic Gàidhlig |

||

|---|---|---|

| Bilingual roadsign in Mallaig: |

|

|

| Pronunciation: | [ˈgɑːlʲɪkʲ] | |

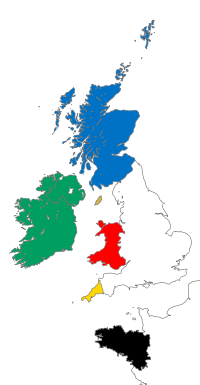

| Spoken in: | Scotland United Kingdom, Canada, United States, Australia | |

| Region: | Parts of the Scottish Highlands, Western Isles, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Formerly all of mainland Scotland, albeit marginally in the southeast (parts of Lothian and Borders) | |

| Total speakers: | 58,552 in Scotland. [1]

92,400 people aged three and over in Scotland had some Gaelic language ability in 2001[2] with an additional 2000 in Nova Scotia. [3] 1,610 speakers in the United States in 2000.[4] 822 in Australia in 2001.[5] 669 in New Zealand in 2006.[6] |

|

| Language family: | Indo-European Celtic Insular Celtic Goidelic Scottish Gaelic |

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | Scotland | |

| Regulated by: | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | gd | |

| ISO 639-2: | gla | |

| ISO 639-3: | gla | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages. This branch also includes the Irish and Manx languages. It is distinct from the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages, which includes Welsh, Cornish, and Breton. Scottish, Manx and Irish Gaelic are all descended from Old Irish. The language is often described as Scottish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic, or Gàidhlig to avoid confusion with the other two Goidelic languages. Outside Scotland, it is occasionally also called Scottish, a usage dating back over 1,500 years; for example Old English Scottas. Scottish Gaelic should not be confused with Scots, because since the 16th century the word Scots has by-and-large been used to describe the Lowland Anglic language, which developed from the northern form of early Middle English. In Scottish English, Gaelic is pronounced [ˈgaːlɪk]; outside Scotland, it is usually pronounced /ˈgeɪlɪk/.

History

Scottish Gaelic, a descendant of the Goidelic branch of Celtic and closely related to Irish, is the traditional language of the Scotti or Gaels, and became the historical language of the majority of Scotland after it replaced Cumbric, Pictish and Old Norse. It also replaced English in considerable areas.[7] It is not clear how long Gaelic has been spoken in what is now Scotland; it has lately been proposed that it was spoken in Argyll before the Roman period, but no consensus has been reached on this question. However, the consolidation of the kingdom of Dál Riata around the 4th century, linking the ancient province of Ulster in the north of Ireland and western Scotland, accelerated the expansion of Gaelic, as did the success of the Gaelic-speaking church establishment. Placename evidence shows that Gaelic was spoken in the Rhinns of Galloway by the 5th or 6th century.

The Gaelic language eventually displaced Pictish north of the Forth, and until the late 15th century it was known in English as Scottis. Gaelic began to decline in mainland Scotland by the beginning of the 13th century, and with this went a decline in its status as a national language. By the beginning of the 15th century, the highland-lowland line was beginning to emerge.

By the early 16th century, English speakers gave the Gaelic language the name Erse (meaning Irish) and thereafter it was invariably the collection of Middle English dialects spoken within the Kingdom of the Scots that they referred to as Scottis (whence Scots). This was ironic as it was at this time that Gaelic was developing its distinctly Scottish forms characteristic of the Modern period[8]. Nevertheless, Gaelic has never been entirely displaced of national language status, and is still recognised by many Scots, whether or not they speak Gaelic, as being a crucial part of the nation's culture. Of course, others may view it primarily as a regional language of the highlands and islands.

Gaelic has a rich oral (beul-aithris) and written tradition, having been the language of the bardic culture of the Highland clans for several centuries. The language preserved knowledge of and adherence to pre-feudal laws and customs (as represented, for example, by the expressions tuatha and dùthchas). The language suffered especially as Highlanders and their traditions were persecuted after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, and during the Highland Clearances, but pre-feudal attitudes were still evident in the complaints and claims of the Highland Land League of the late 19th century: this political movement was successful in getting members elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Land League was dissipated as a parliamentary force by the 1886 Crofters' Act and by the way the Liberal Party was seen to become supportive of Land League objectives.

The first translation of the Bible into Scottish Gaelic was not made until 1767 when Dr James Stuart of Killin and Dugald Buchanan of Rannoch produced a translation of the New Testament [compare Talk:Scottish Gaelic#Bible in Gaelic though]. Very few European languages have made the transition to a modern literary language without an early modern translation of the Bible. The lack of such a translation until the late eighteenth century undoubtedly contributed to the decline of Scottish Gaelic.[9]

Scottish Gaelic may be more correctly known as Highland Gaelic to distinguish it from the now defunct Lowland Gaelic. Lowland Gaelic was a form of Irish Gaelic spoken in Galloway, where extensive settlement from the Norse/Gaelic communities of the Isles[10] as the language of a significant proportion of the elite that governed communities that spoke either the 'native' Brythonic language of the region or the Old English that had greatly increased in significance since the Northumbrian conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries. By the end of the Middle Ages, Lowland Gaelic had largely been replaced by the Middle English/Lowland Scots that descended from the Anglo-Saxon tongue, while the Brythonic language had disappeared. There is, however, no evidence of a linguistic border following the topographical north-south differences. Similarly, there is no evidence from placenames of significant linguistic differences between, for example, Argyll and Galloway. Dialects on both sides of the Straits of Moyle (the North Channel) linking Scottish Gaelic with Irish are now extinct.

According to a reference in The Carrick Covenanters by James Crichton (Undated. “Printed at the Office of Messrs. Arthur Guthrie and Sons Ltd., 49 Ayr Road, Cumnock.”), the last place in the Lowlands where Gaelic was still spoken was the village of Barr in Carrick (only a few miles inland to the east of Girvan, but at one time very isolated).

| Year | Scottish population | Speakers of Gaelic only | Speakers of Gaelic and English | Speakers of Gaelic and English as % of population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1755 | 1,265,380 | 289,798 | N/A | N/A (22.9 monoglot Gaelic) |

| 1800 | 1,608,420 | 297,823 | N/A | N/A (18.5 monoglot Gaelic) |

| 1881 | 3,735,573 | 231,594 | N/A | N/A (6.1 monoglot Gaelic) |

| 1891 | 4,025,647 | 43,738 | 210,677 | 5.2 |

| 1901 | 4,472,103 | 28,106 | 202,700 | 4.5 |

| 1911 | 4,760,904 | 18,400 | 183,998 | 3.9 |

| 1921 | 4,573,471 | 9,829 | 148,950 | 3.3 |

| 1931 | 4,588,909 | 6,716 | 129,419 | 2.8 |

| 1951 | 5,096,415 | 2,178 | 93,269 | 1.8 |

| 1961 | 5,179,344 | 974 | 80,004 | 1.5 |

| 1971 | 5,228,965 | 477 | 88,415 | 1.7 |

| 1981 | 5,035,315 | N/A | 82,620 | 1.6 |

| 1991 | 5,083,000 | N/A | 65,978 | 1.4 |

| 2001 | 5,062,011 | N/A | 58,652 | 1.2 |

Current distribution in Scotland

The 2001 UK Census showed a total of 58,652 Gaelic speakers in Scotland (1.2% of population over three years old).[11] Compared to the 1991 Census, there has been a diminution of approximately 7,300 people (11% of the total), meaning that Gaelic decline (language shift) in Scotland is continuing. To date, attempts at language revival or reversing language shift have been met with limited success.

Considering the data related to Civil Parishes (which permit a continuous study of Gaelic status since the 19th century), two new circumstances have taken place, which are related to this decline:

- No parish in Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 75% any more (the highest value corresponds to Barvas, Lewis, with 74.7%).

- No parish in mainland Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 25% any more (the highest value corresponds to Lochalsh, Highland, with 20.8%).

The main stronghold of the language continues to be the Western Isles (Na h-Eileanan Siar), where the overall proportion of speakers remains at 61.1% and all parishes return values over 50%. The Parish of Kilmuir in Northern Skye is also over this threshold of 50%.

Proportions over 20% register throughout the isles of Skye, Raasay, Tiree, Islay and Colonsay, and the already mentioned parish of Lochalsh in Highland.

Regardless of this, the weight of Gaelic in Scotland is now much reduced. From a total of almost 900 Civil Parishes in Scotland:

- Only 9 of them have a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 50%.

- Only 20 of them have a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 25%.

- Only 39 of them have a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 10%.

Outside the main Gaelic-speaking areas a relatively high proportion of Gaelic-speaking people are, in effect, socially isolated from other Gaelic-speakers and as a result they obtain few opportunities to use the language.

Orthography

- Further information: Scottish Gaelic alphabet

Prehistoric (or Ogham) Irish, the precursor to Old Irish, in turn the precursor to Modern Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx Gaelic, was written in a carved writing called Ogham. Ogham consisted of marks made above or below a horizontal line. With the advent of Christianity in the 5th century the Latin alphabet was introduced to Ireland. The Goidelic languages have historically been part of a dialect continuum stretching from the south of Ireland, the Isle of Man, to the north of Scotland.

Classical Gaelic was used as a literary language in Ireland until the 17th century and in Scotland until the 18th century. Later orthographic divergence is the result of more recent orthographic reforms resulting in standardised pluricentric diasystems.

The 1767 New Testament historically set the standard for Scottish Gaelic. Around the time of World War II, Irish spelling was reformed and the Official Standard or Caighdeán Oifigiúil introduced. Further reform in 1957 eliminated some of the silent letters which are still used in Scottish Gaelic. The 1981 Scottish Examinations Board recommendations for Scottish Gaelic, the Gaelic Orthographic Conventions, were adopted by most publishers and agencies, although they remain controversial among some academics, most notably Ronald Black.[12]

The modern Scottish Gaelic alphabet has 18 letters:

- A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, T, U.

The letter h, now mostly used to indicate lenition of a consonant, was in general not used in the oldest orthography, as lenition was instead indicated with a dot over the lenited consonant. The letters of the alphabet were traditionally named after trees (see Scottish Gaelic alphabet), but this custom has fallen out of use.

The quality of consonants is indicated in writing by the vowels surrounding them. So-called "slender" consonants are palatalised while "broad" consonants are velarised. The vowels e and i are classified as slender, and a, o, and u as broad. The spelling rule known as caol ri caol agus leathann ri leathann ("slender to slender and broad to broad") requires that a word-medial consonant or consonant group followed by a written i or e be also preceded by an i or e; and similarly if followed by a, o or u be also preceded by an a, o, or u. Consonant quality (palatalised or non-palatalised) is then indicated by the vowels written adjacent to a consonant, and the spelling rule gives the benefit of removing possible uncertainty about consonant quality at the expense of adding additional purely graphic vowels that may not be pronounced. For example, compare the t in slàinte [slaːntʃə] with the t in bàta [paːtə].

The rule has no effect on the pronunciation of vowels. For example, plurals in Gaelic are often formed with the suffix -an, for example, bròg [proːk] (shoe) / brògan [proːkən] (shoes). But because of the spelling rule, the suffix is spelled -ean (but pronounced the same) after a slender consonant, as in taigh [tʰɤj] (house) / taighean [tʰɤjən] (houses) where the written e is purely a graphic vowel inserted to conform with the spelling rule because an i precedes the gh.

In changes promoted by the Scottish Examination Board from 1976 onwards, certain modifications were made to this rule. For example, the suffix of the past participle is always spelled -te, even after a broad consonant, as in togte "raised" (rather than the traditional togta).

Where pairs of vowels occur in writing, it is sometimes unclear which vowel is to be pronounced and which vowel has been introduced to satisfy this spelling rule.

Unstressed vowels omitted in speech can be omitted in informal writing. For example:

- Tha mi an dòchas. ("I hope.") > Tha mi 'n dòchas.

Once Gaelic orthographic rules have been learned, the pronunciation of the written language is in general quite predictable. However learners must be careful not to try to apply English sound-to-letter correspondences to written Gaelic, otherwise mispronunciations will result. Gaelic personal names such as Seònaid [ˈʃɔːnɛdʒ] are especially likely to be mispronounced by English speakers.

Scots English orthographic rules have also been used at various times in Gaelic writing. Notable examples of Gaelic verse composed in this manner are the Book of the Dean of Lismore and the Fernaig manuscript.

Pronunciation

Vowels

Gaelic vowels can have a grave accent, with the letters à, è, ì, ò, ù. Traditional spelling also uses the acute accent on the letters á, é and ó, but texts which follow the spelling reform only use the grave.

-

A table of vowels with pronunciations in the IPA Spelling Pronunciation English equivalent As in a, á [a], [a] cat bata, lochán à [aː] father/calm bàta e [ɛ], [e] get le, teth è, é [ɛː], [eː] wary, late/lady sèimh, fhéin i [i], [iː] tin, sweet sin, ith ì [iː] evil, machine mìn o [ɔ], [o] top poca, bog ò, ó [ɔː], [oː] jaw, boat/go pòcaid, mór u [u] brute tur ù [uː] brood tùr

Note: The English equivalents given are only approximate, and refers most closely to the Scottish pronunciation of Standard English. The vowel most commonly found in 'Southern' English cat is not [a] but [æ], just as the [a:] in English father is [ɑː]. The "a" in English late in Scots English is the pure vowel [e:] rather than the more general diphthong [eɪ]. The same is true for the "o" in English boat, [o:] in Scots, instead of the diphthong [əʊ].

Digraphs

-

A table of diphthongs with pronunciations in the IPA Spelling Pronunciation As in ai [a], [ə], [ɛ], [i] (stressed syllable) caileag, ainm [ɛnʲəm]; (unstressed syllables) iuchair, geamair, dùthaich ài [aː], [ai] àite, bara-làimhe ao; aoi [ɯː]; [ɯi] caol; gaoil, laoidh ea [ʲa], [e], [ɛ] geal, deas, bean eà [ʲaː] ceàrr èa [ɛː] nèamh ei [e], [ɛ] eile, ainmeil èi [ɛː] cèilidh éi [eː] fhéin eo [ʲɔ] deoch eò(i) [ʲɔː] ceòl, feòil eu [eː], (Northern) [ia] ceum, feur ia [iə], [ia] biadh, dian io [i], [ᴊũ] fios, fionn ìo [iː], [iə] sgrìobh, mìos iu [ᴊu] piuthar iù(i) [ᴊuː] diùlt, diùid oi [ɔ], [ɤ] boireannach, goirid òi [ɔː] fòill ói [oː] còig ua(i) [uə], [ua] ruadh, uabhasach, duais ui [u], [ɯ], [ui] muir, uighean, tuinn ùi [uː] dùin

Consonants

Most letters are pronounced similarly to other European languages. The broad consonants t and d and often n have a dental articulation (as in Irish and the Romance and Slavic languages) in contrast to the alveolar articulation common in English and other Germanic languages). Non-palatal r is an alveolar trill (like Italian or Spanish rr.)

-

Labial Dental/

AlveolarPost

alveolarPalatal Velar Nasal m n̪ ɲ ŋ Plosive p, b t̪, d̪ k, g Affricate ʧ, ʤ Fricative f, v s ʃ x, ɣ Approximant j Lateral l, ɫ ʎ Trill r Flap ɾ

Aspiration vs Voicing of Gaelic Stops

The "voiced" stops /b, d, g/ are not phonetically voiced [+voice] in Gaelic, but rather voiceless unaspirated. Thus Gaelic /b, d, g/ are really phonetically [p, t, k] [-voice, -aspirated]. Note that in the dialects of the far south and far north-east, /b, d, g/ are voiced, just as they are in Manx and Irish.

The "voiceless" stops /p, t, k/ are voiceless and strongly aspirated (postaspirated in initial position, preaspirated in medial or final position). That is, in syllable onsets Gaelic /p, t, k/ are phonetically [ph,th,kh], but they are [hp,ht,xk] in syllable-final position. Note that preaspirated stops can also be found in Icelandic. Thus, Gaelic /p, t, k/ are [-voice, +aspirated].

In some Gaelic dialects (particularly thew north-west), stops at the beginning of a stressed syllable become voiced when they follow a nasal consonant, for example: taigh 'a house' is [tʰɤi] but an taigh 'the house' is [ən dʰɤi]; cf. also tombaca 'tobacco' [tʰomˈbaxkə]. In such dialects the -aspirate stops /b, d, g/ tend to be completely nasalised, thus dorus 'a door' is [tɔrəs]], but an dorus 'the door' is [ə nɔrəs]. This can cause confusion for second language speakers, such as mispronouncing an mòd 'the meeting' so that it sounds like an bod 'the penis'.

Broad vs Slender

Scottish Gaelic along with Modern Irish, Manx (and in all three a characteristic descending from Old and Middle Irish) contains what are traditionally referred to as broad (velarization/velarized) and slender (palatalized) consonants. Historically, Primitive Irish consonants preceding the front vowels /e/ and /i/ developed a [j] offglide similar to the palatalized consonants found in Russian (Thurneysen 1946, 1980). Celtic linguists traditionally transcribe slender consonants as /C´/, while the consonants preceding the non-front vowels /a/, /o/ abd /u/ developed a velarised offglide, normally not marked by Celtic linguists, leaving it as the unmarked part of the velarised-palatilised contrast.

In the modern languages, there is sometimes a stronger contrast from Old Gaelic in the assumed meaning of "broad" and "slender". In the modern languages, the phonetic difference between "broad" and "slender" consonants can be more complex than mere 'velarization'/'palatalization'. For instance, the Gaelic slender s, phonetically transcribed as /s´/, is actually pronounced as the postalveolar fricative [ʃ], not as [sʲ]. See the consonant chart below for details. Note that not all such 'variant' phonetic forms are shown in the chart; for example, in some dialects, broad /l/ (dental), is actually pronounced as either a /w/ or a /ɣʷ/, and slender /r/ in some dialects sounds more like a /z/.

Lenition and spelling

The lenited consonants have special pronunciations: bh and mh are [v]; ch is [x] or [ç]; dh, gh is [ʝ] or [ɣ]; th is [h], [ʔ], or silent; ph is [f]. Lenition of l n r is not shown in writing. The digraph fh is almost always silent, with only the following three exceptions: fhèin, fhathast, and fhuair, where it is pronounced as [h].

-

A table of consonants with pronunciations in the IPA. Based on Gillies (1993). Radical Lenited Orthography Broad Slender Orthography Broad Slender b (initial) [p] [pj] bh [v] [vj] b (final) [p] [jp] bh [v] [vj] c (initial) [kʰ] [kʰʲ] ch [x] [ç] c (final) [xk] [kʰʲ] ch [x] [ç] d [t̪] [ʤ] dh [ɣ] [ʝ] f (initial) [f] [fj] fh silent silent f (final) [f] [jf] fh silent silent g [k] [kʲ] gh [ɣ] [ʝ] l [ɫ̪] [ʎ] l no change [ʎ] or [l] m [m] [mj] mh [v] [vj] n [n̪] [ɲ] n [n] [ɲ] or [n] p (initial) [pʰ] [pjʰ] ph [f] [fj] p (final) [hp] [jhp] ph [f] [fj] r' [r] same as broad r [ɾ] [ɾ] s [s̪] [ʃ] sh [h] [hʲ] t (initial) [t̪ʰ] [tʃʰ] th [h] [hʲ] t (final) [ht̪] [htʃ] th [h] or silent [hj] or [j]

Stress

Stress is usually on the first syllable: for example drochaid 'a bridge' [ˈtroxaʤ]. (Knowledge of this fact alone would help avoid many a mispronunciation of Highland placenames, for example Mallaig is [ˈmaɫakʲ].) Note, though, that when a placename consists of more than one word in Gaelic, the Anglicised form is liable to have stress on the last element: Tyndrum [taɪnˈdrʌm] < Taigh an Droma [tʰɤin ˈdromə]. This is because, unlike English, Gaelic word order places the adjective and nominal genitives after the noun.

Epenthesis

A distinctive characteristic of Gaelic pronunciation (which has influenced Scottish Engli9sh dialects – cf. girl [gʌrəl] and film [fɪləm]) is the insertion of epenthetic vowels between certain adjacent consonants, specifically, between sonorants (l or r) and certain following consonants:

- tarbh (bull) — [t̪ʰarav]

- Alba (Scotland) — [aɫ̪apa].

Elision

Schwa [ə] at the end of a word is dropped when followed by a word beginning with a vowel. For example:

- duine (a man) — [ˈt̪ɯɲə]

- an duine agad (your man) — [ən ˈt̪ɯɲ akət̪]

Tones

Word tones are a linguistic device for distinguishing otherwise identical-sounding words. Among the most well-known cases of languages using word tones are Chinese and Vietnamese, but tonal languages are also to be found in Europe, e.g. Norwegian and Swedish. Of all the Celtic languages, only the dialects of Lewis (Ternes 1980) and Sutherland (Dorian 1978, 60-1) in the extreme north of the Gaelic-speaking area have tones. Phonetically and historically, these resemble the tones of Norway, Sweden and western Denmark. We may assume that the presence of these tones in Lewis and Sutherland is to be attributed to Viking influence. Several hundred pairs can be found in the Scandinavian languages differentiated by having Tone 1 and Tone 2. In Lewis Gaelic it is difficult to find minimum pairs. Among the rare examples are: bodh(a) (underwater rock) and bò (cow), both pronounced as bò; and fitheach (raven) and fiach (debt), both pronounced as fiach. Another example (with svaranhakti) is the tonal difference between ainm (Tone 2) and anam which has the tonal contour appropriate to a disyllable. These tonal differences are not to be found in Ireland or elsewhere in the Scottish Gaeltachd.[13]

Grammar

Official recognition

Gaelic has long suffered from its lack of use in educational and administrative contexts and has even been suppressed in the past[14] but it has achieved a degree of official recognition with the passage of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005.

Media

As well as being taught in schools, including some in which it is the medium of instruction, it is also used by the local council in the Western Isles, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. The BBC also operates a Gaelic language radio station Radio nan Gàidheal (which regularly transmits joint broadcasts with its Irish counterpart Raidió na Gaeltachta), and there are also television programmes in the language on the BBC and on the independent commercial channels, usually subtitled in English. The ITV franchisee in the north of Scotland, STV North (formerly Grampian Television) produces some non-news programming in Scottish Gaelic. The ITV franchise in central Scotland, STV Central produces an number of Scottish Gaelic programmes for both BBC Alba and its own main channel. Viewers of Freeview, a non-subscription digital TV service, can receive the channel TeleG, which broadcasts for an hour every evening. On 19 September 2008 a new Gaelic TV service launched, broadcasting across Europe on Sky Digital and across the UK on Freesat. Despite initial announcements to the contrary, the channel is not yet available on digital cable television. The channel BBC Alba is being operated in partnership between BBC Scotland and MG ALBA - a new organisation funded by the Scottish Government, which works to promote the Gaelic language in broadcasting.

Geography

Bilingual road signs (in both Gaelic and English) are gradually being introduced throughout the Gaelic-speaking regions in the Highlands (recently revealed roadsigns for Castletown in Caithness seem to indicate the Highland Council's intention to introduce bilingual signage into all areas of the Highlands, whether they have a tradition of Gaelic or not, against the wishes of the residents[2]) which have and elsewhere across the nation. In many cases, this has simply meant re-adopting the traditional spelling of a name.

The Ordnance Survey has acted in recent years to correct many of the mistakes that appear on maps. They announced in 2004 that they intended to make amends for a century of Gaelic ignorance and set up a committee to determine the correct forms of Gaelic place names for their maps.

Parliament

Historically, Gaelic has not received the same degree of official recognition from the UK Government as Welsh. With the advent of devolution, however, Scottish matters have begun to receive greater attention, and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act was enacted by the Scottish Parliament on 21 April 2005.

The key provisions of the Act are[15]:

- Establishing the Gaelic development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, (BnG), on a statutory basis with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language and to promote the use and understanding of Gaelic.

- Requiring BnG to prepare a National Gaelic Language Plan for approval by Scottish Ministers.

- Requiring BnG to produce guidance on Gaelic Education for education authorities.

- Requiring public bodies in Scotland, both Scottish public bodies and cross border public bodies insofar as they carry out devolved functions, to develop Gaelic language plans in relation to the services they offer, if requested to do so by BnG.

Fàilte gu stèisean Dùn Èideann

("Welcome to Edinburgh station")

Following a consultation period, in which the government received many submissions, the majority of which asked that the bill be strengthened, a revised bill was published with the main improvement that the guidance of the Bòrd is now statutory (rather than advisory).

In the committee stages in the Scottish Parliament, there was much debate over whether Gaelic should be given 'equal validity' with English. Due to Executive concerns about resourcing implications if this wording was used, the Education Committee settled on the concept of 'equal respect'. It is still not clear if the ambiguity of this wording will provide sufficient legal force to back up the demands of Gaelic speakers against the whims of public bodies.

The Act was passed by the Scottish Parliament unanimously, with support from all sectors of the Scottish political spectrum on the 21st of April 2005.

Education

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872, which completely ignored Gaelic, and led to generations of Gaels being forbidden to speak their native language in the classroom, is now recognised as having dealt a major blow to the language. People still living can recall being beaten for speaking Gaelic in school.[16] The first modern solely Gaelic-medium secondary school, Sgoil Ghàidhlig Ghlaschu (‘Glasgow Gaelic School’), was opened at Woodside in Glasgow in 2006 (61 partially Gaelic-medium primary schools and approximately a dozen Gaelic-medium secondary schools also exist). A total of 2,092 primary pupils are enrolled in Gaelic-medium primary education in 2006-7.

In Nova Scotia, there are somewhere between 500 and 1,000 native speakers, most of them now elderly. In May 2004, the Provincial government announced the funding of an initiative to support the language and its culture within the province.

In Prince Edward Island, the Colonel Gray High School is now offering two courses in Gaelic, an introductory and an advanced course, both language and history are taught in these classes. This is the first recorded time that Gaelic has ever been taught as an official course on Prince Edward Island.

The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of Gaelic. Along with Irish and Welsh, Gaelic is designated under Part III of the Charter, which requires the UK Government to take a range of concrete measures in the fields of education, justice, public administration, broadcasting and culture.

The Columba Initiative, also known as colmcille (formerly Iomairt Cholm Cille), is a body that seeks to promote links between speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Irish.

However, given there are no longer any monolingual Gaelic speakers,[17] following an appeal in the court case of Taylor v Haughney (1982), involving the status of Gaelic in judicial proceedings, the High Court ruled against a general right to use Gaelic in court proceedings.[18]

Under the provisions of the 2005 Act, it will ultimately fall to BnG to secure the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland.

Church

In the Western Isles, the isles of Lewis, Harris and North Uist have a Presbyterian majority (largely Church of Scotland - Eaglais na h-Alba in Gaelic, Free Church of Scotland and Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland.) The isles of South Uist and Barra have a Catholic majority. All these churches have Gaelic-speaking congregations throughout the Western Isles.

There are Gaelic-speaking congregations in the Church of Scotland, mainly in the Highlands and Islands, but also in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Notable city congregations with regular services in Gaelic are St Columba's Church, Glasgow and Greyfriars Tolbooth & Highland Kirk, Edinburgh. Leabhar Sheirbheisean - a shorter Gaelic version of the English-language Book of Common Order - was published in 1996 by the Church of Scotland, ISBN 0-907624-12-X.

The relationship between the Church and Gaelic has not always been an easy one. The widespread use of English in worship has often been suggested as one of the historic reasons for Gaelic's decline. Whilst the Church of Scotland is supportive today, there is, however, an increasing difficulty in being able to find Gaelic-speaking ministers. The Free Church also recently announced plans to reduce their Gaelic provision by abolishing Gaelic-language communion services, citing both a lack of ministers and a desire to have their congregations united at communion time.[19]

Sport

The most notable use of the language in sport is that of the Camanachd Association, the shinty society, who have a bilingual logo.

In the mid-1990s, the Celtic League started a campaign to have the word "Alba" on the Scottish football and rugby tops. Since 2005, the SFA have supported the use of Scots Gaelic on their teams's strip in recognition of the language's revival in Scotland.[20] However, the SRU is still being lobbied to have "Alba" on the national rugby strip. [21] [22]

Some sports coverage, albeit at a small level, takes place in Scottish Gaelic broadcasting.

Personal names

Scottish Gaelic has a number of personal names, such as Aiden, Ailean, Aonghas, Dòmhnall, Donnchadh, Coinneach, Murchadh, for which there are traditional forms in English (Alan, Angus, Donald, Duncan, Kenneth, Murdo). There are also distinctly Scottish Gaelic forms of names that belong to the common European stock of given names, such as: Iain (John), Alasdair (Alexander), Uilleam (William), Catrìona (Catherine), Raibert (Robert), Cairistìona (Christina), Anna (Ann), Màiri (Mary), Seumas (James), Pàdraig (Patrick) and Tómas(Thomas). Some names have come into Gaelic from Old Norse, for example: Somhairle ( < Somarliðr), Tormod (< Þórmóðr), Torcuil (< Þórkell, Þórketill), Ìomhair (Ívarr). These are conventionally rendered in English as Sorley (or, historically, Somerled), Norman, Torquil, and Iver (or Evander). There are other, traditional, Gaelic names which have no direct equivalents in English: Oighrig, which is normally rendered as Euphemia (Effie) or Henrietta (Etta) (formerly also as Henny or even as Harriet), or, Diorbhal, which is "matched" with Dorothy, simply on the basis of a certain similarity in spelling; Gormul, for which there is nothing similar in English, and it is rendered as 'Gormelia' or even 'Dorothy'; Beathag, which is "matched" with Becky (> Rebecca) and even Betsy, or Sophie.

Many of these are now regarded as old-fashioned, and are no longer used (which is, of course, a feature common to many cultures: names go out of fashion). As there is only a relatively small pool of traditional Gaelic names from which to choose, some families within the Gaelic-speaking communities have in recent years made a conscious decision when naming their children to seek out names that are used within the wider English-speaking world. These names do not, of course, have an equivalent in Gaelic. What effect that practice (if it becomes popular) might have on the language remains to be seen. At this stage (2005), it is clear that some native Gaelic-speakers are willing to break with tradition. Opinion on this practice is divided; whilst some would argue that they are thereby weakening their link with their linguistic and cultural heritage, others take the opposing view that Gaelic, as with any other language, must retain a degree of flexibility and adaptability if it is to survive in the modern world at all.

The well-known name Hamish, and the recently established Mhairi (pronounced [va:ri]) come from the Gaelic for, respectively, James, and Mary, but derive from the form of the names as they appear in the vocative case: Seumas (James) (nom.) → Sheumais (voc.), and, Màiri (Mary) (nom.) → Mhàiri (voc.).

The most common class of Gaelic surnames are, of course, those beginning with mac (Gaelic for son), such as MacGillEathain (MacLean). The female form is nic (Gaelic for daughter), so Catherine MacPhee is properly called in Gaelic, Caitrìona Nic a' Phì. [Strictly, "nic" is a contraction of the Gaelic phrase "nighean mhic", meaning "daughter of the son", thus Nic Dhomhnuill, really means "daughter of MacDonald" rather than "daughter of Donald".] Although there is a common misconception that "mac" means "son of", the "of" part actually comes from the genitive form of the patronymic that follows the prefix "Mac", e.g., in the case of MacNéill, Néill (of Neil) is the genitive form of Niall (Neil).

Several colours give rise to common Scottish surnames: bàn (Bain - white), ruadh (Roy - red), dubh (Dow - black), donn (Dunn - brown), buidhe (Bowie - yellow).

Loanwords

The majority of Scottish Gaelic's vocabulary is native Celtic. There are a large number of borrowings from Latin, (muinntir, Didòmhnaich), ancient Greek, especially in the religious domain (eaglais, Bìoball from Ekklesia and Biblia), Norse (eilean, sgeir), Hebrew (Sàbaid, Aba) and Lowland Scots (aidh, bramar).

In common with other Indo-European languages, the neologisms which are coined for modern concepts are typically based on Greek or Latin, although written in Gaelic orthography; television, for instance, becomes telebhisean (cian-dhealbh could also be used), and computer becomes coimpiùtar (aireamhadair, bocsa-fiosa or bocsa-sgrìobhaidh could also be used). Although native speakers frequently use an English word for which there is a perfectly good Gaelic equivalent, they will, without thinking, simply adopt the English word and use it, applying the rules of Gaelic grammar, as the situation requires. With verbs, for instance, they will simply add the verbal suffix (-eadh, or, in Lewis, -igeadh, as in, "Tha mi a' watcheadh (Lewis, "watchigeadh") an telly" (I am watching the television), instead of "Tha mi a' coimhead air a' chian-dhealbh". This was remarked upon by the minister who compiled the account covering the parish of Stornoway in the New Statistical Account of Scotland, published over 170 years ago. However, as Gaelic medium education grows in popularity, a newer generation of literate Gaels is becoming more familiar with modern Gaelic vocabulary.

Going in the other direction, Scottish Gaelic has influenced the Scots language (gob) and English, particularly Scottish Standard English. Loanwords include: whisky, slogan, brogue, jilt, clan, strontium (from Strontian), trousers, as well as familiar elements of Scottish geography like ben (beinn), glen (gleann) and loch. Irish has also influenced Lowland Scots and English in Scotland, but it is not always easy to distinguish its influence from that of Scottish Gaelic. See List of English words of Scottish Gaelic origin

Source: An Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language, Alexander MacBain.

Common Scottish Gaelic words and phrases with Irish and Manx equivalents

- Further information: Differences between Scottish Gaelic and Irish

| Scottish Gaelic Phrase | Irish Equivalent | Manx Gaelic Equivalent | Rough English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fàilte | Fáilte | Failt | Welcome |

| Halò | Haileo or Dia dhuit (trad., lit.: "God be with you") | Hello | Hello |

| Latha math | Lá maith | Laa mie | Good day |

| Ciamar a tha thu? | Conas atá tú? (Cén chaoi a bhfuil tú? in Connacht or Cad é mar atá tú? in Ulster) | Kys t'ou? | How are you? |

| Ciamar a tha sibh? | Conas atá sibh? (Cén chaoi a bhfuil sibh? in Connacht or Cad é mar atá sibh? in Ulster) | Kanys ta shiu? | How are you? (plural, singular formal) |

| Madainn mhath | Maidin mhaith | Moghrey mie | Good morning |

| Feasgar math | Trathnóna maith | Fastyr mie | Good afternoon |

| Oidhche mhath | Oíche mhaith | Oie vie | Good night |

| Ma 's e do thoil e | Más é do thoil é | My saillt | If you please |

| Ma 's e (bh)ur toil e | Más é bhur dtoil é | My salliu | If you please (plural, singular formal) |

| Tapadh leat | Go raibh maith agat | Gura mie ayd | Thank you |

| Tapadh leibh | Go raibh maith agaibh | Gura mie eu | Thank you (plural, singular formal) |

| Dè an t-ainm a tha ort? | Cad é an t-ainm atá ort? or Cad is ainm duit? | Cre'n ennym t'ort? | What is your name? |

| Dè an t-ainm a tha oirbh? | Cad é an t-ainm atá oraibh? or Cad is ainm daoibh? | Cre'n ennym t'erriu? | What is your name?(plural, singular formal) |

| Is mise... | Is mise... | Mish... | I am... |

| Slàn leat | Slán leat | Slane lhiat | Goodbye |

| Slàn leibh | Slán libh | Slane lhiu | Goodbye (plural, singular formal) |

| Dè a tha seo? | Cad é seo? | Cre shoh? | What is this? |

| Slàinte | Sláinte | Slaynt | "health" (used as a toast [cf. English "cheers"] when drinking) |

Gaelic in the Lowlands

According to a reference in The Carrick Covenanters by James Crichton, the last place in the Scottish Lowlands where Gaelic was spoken was the village of Barr on the River Stinchar in Ayrshire. Barr was once regarded as one of the most isolated places in that part of Scotland, though situated only a few miles from Girvan as the crow flies. Crichton gives neither date nor details. For further discussion on the subject of Gaelic in the South of Scotland, see articles Gàidhlig Ghallghallaibh agus Alba-a-Deas ("Gaelic of Galloway and Southern Scotland") and Gàidhlig ann an Siorramachd Inbhir-Àir ("Gaelic in Ayrshire") by Garbhan MacAoidh, published in GAIRM Numbers 101 and 106.

Qualifications in the Gaelic Language

Examinations

The Scottish Qualifications Authority offer two streams of Gaelic examination across all levels of the syllabus: Gaelic for learners (equivalent to the modern foreign languages syllabus) and Gaelic for native speakers (equivalent to the English syllabus).

An Comunn Gàidhealach performs assessment of spoken Gaelic, resulting in the issue of a Bronze Card, Silver Card or Gold Card. Syllabus details are available on An Comunn's website. These are not widely recognised as qualifications, but are required for those taking part in certain competitions at the annual mods.

Higher & Further Education

A number of Scottish universities offer full-time degrees including a Gaelic language element, usually graduating as Celtic Studies.

St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada also offers a Celtic Studies degree, optionally with a large Gaelic language element.

Courses at the UHI Millenium Institute

The University of the Highlands and Islands offers a range of Gaelic courses at Cert HE, Dip HE, BA (ordinary), BA (Hons) and MA, and offers opportunities for postgraduate research through the medium of Gaelic. The majority of these courses are available as residential courses at the Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. A number of other colleges offer the one year certificate course, which is also available on-line (pending accreditation).

Lews Castle College's Benbecula campus offers an independent 1 year course in Gaelic and Traditional Music (FE, SQF level 5/6).

See also

- Affection (linguistics)

- Book of Deer

- Bungee language

- Scottish Gaelic in Canada

- Differences between Scottish Gaelic and Irish

- Gaelicization

- Gàidhealtachd

- Gaelic broadcasting in Scotland

- Gaelic Digital Service

- Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005

- Gaelic road signs in Scotland

- Galwegian Gaelic

- Greyfriars Tolbooth & Highland Kirk

- Languages in the United Kingdom

- List of Scottish Gaelic speakers by scottish council areas

- List of television channels in Celtic languages

- List of Celtic language media

- Middle Irish

- Nancy Dorian

- Gaelic grammar

- Lowland Scots

- The Mòd

- St Columba's Church, Glasgow

- William J. Watson

- Irish language revival

References

- ↑ CnaG ¦ Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic speakers by council area

- ↑ "News Release - Scotland's Census 2001 - Gaelic Report" from General Registrar for Scotland website, 10 October 2005. Retrieved 27 December 2007

- ↑ "Oifis Iomairtean na Gaidhlig

- ↑ "Language by State - Scottish Gaelic" on Modern Language Association website. Retrieved 27 December 2007

- ↑ "Languages Spoken At Home" from Australian Government Office of Multicultural Interests website. Retrieved 27 December 2007

- ↑ Languages Spoken:Total Responses from Statistics New Zealand website. Retrieved 5 August 2008

- ↑ W. F. H. Nicolaisen: Scottish Place-Names, B. T. Batsford, London 1986, p.133

- ↑ Gaelic - A Past and Future Prospect. MacKinnon, Kenneth. Saltire Society Edinburgh 1991. p41

- ↑ Mackenzie, Donald W. (1990-92). "The Worthy Translator: How the Scottish Gaels got the Scriptures in their own Tongue". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness 57: 168–202.

- ↑ [1] Report by Alistair Livingston to the Scottish Parliament

- ↑ Kenneth MacKinnon (2003). "Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic Language – first results". Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ The Board of Celtic Studies Scotland (1998) Computer-Assisted Learning for Gaelic: Towards a Common Teaching Core. The orthographic conventions were revised by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) in 2005: "Gaelic Orthographic Conventions 2005" (PDF). SQA publication BB1532. Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ Word tones and svarabhakti by R.D. Clement, Linguistic Survey of Scotland, University of Edinburgh, in The Companion to Gaelic Scotland, p. 108, Ed. Derick S. Thomson, GAIRM, Glasgow 1994.

- ↑ See Kenneth MacKinnon (1991) Gaelic: A Past and Future Prospect. Edinburgh: The Saltire Society.

- ↑ Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005.

- ↑ Pagoeta, Mikel Morris (2001). Europe Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. pp. 416. ISBN-X.

- ↑ UK Ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Working Paper 10 - R.Dunbar, 2003

- ↑ Official Status for Gaelic: Prospects and Problems

- ↑ Free Church plans to scrap Gaelic communion service - Scotsman.com News

- ↑ "BBC Scotland - Gaelic added to Scotland strips".

- ↑ Scottish Rugby Union: "Put 'Alba' on Scottish Ruby Shirt" | Facebook

- ↑ "BBC Alba - Gàidhlig air lèintean rugbaidh na h-Alba".

Resources

- Gillies, H. Cameron (1896) Elements of Gaelic Grammar, Vancouver: Global Language Press (reprint 2006), ISBN 1-897367-02-3 (hardcover), ISBN 1-897367-00-7 (paperback)

- Gillies, William (1993) "Scottish Gaelic", in: Ball, Martin J. and Fife, James (eds) The Celtic Languages (Routledge Language Family Descriptions), London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28080-X (paperback), p. 145–227

- Lamb, William (2001) Scottish Gaelic, Munich: Lincom Europa, ISBN 3-89586-408-0

- MacAoidh, Garbhan (2007) Tasgaidh - A Gaelic Thesaurus, Lulu Enterprises, N. Carolina

- McLeod, Wilson (ed.) (2006) Revitalising Gaelic in Scotland: Policy, Planning and Public Discourse, Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, ISBN 1-903765-59-5

- Robertson, Charles M. (1906–07). "Scottish Gaelic Dialects", The Celtic Review, vol 3 pp. 97–113, 223–39, 319–32.

External links

- Aberdeen University Celtic Department Classes from beginner all the way to degree and PhD level

- Learn Gaelic Classes and Courses across the World

- Scottish Parliament

- Scottish Gaelic Broadcasting Committee

- Scotsman.com News - Scottish Gaelic homepage

- BBC Scotland - Scottish Gaelic homepage

- BBC Scotland - Beag air Bheag

- Beul Aithris - Scottish Gaelic Oral Tradition

- Iomairt Cholm Cille The Columba Initiative

- Comunn na Gàidhlig

- St Columba Gaelic Section Gaelic Resources

- Sabhal Mòr Ostaig - Gaelic-medium College on Skye.

- Scottish Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts - Gaelic college in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Canada.

- Scottish-English Dictionary

- Goidelic Dictionaries

- Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Census information from 1881 to the present, 27 volumes covering all Gaelic-speaking regions

- The Scottish Gaelic feature film Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle

- Gaelic in Scotland Information and links from the Scottish FAQ

- Save Gaelic News links to most current press stories concerning Gaelic.

- SaorsaMedia Resources about the history of Gaelic language and culture in Scotland and North America

- Calum and Catrìona Materials about Gaelic history and culture in Scotland and North America for children

- Tìr nam Blòg A focus point of the Gàidhlig blogging community (founded 16 December 2005)

- Oi Polloi Gaelic punk music from Edinburgh

- Mill a h-Uile Rud Gaelic punk music from Seattle

Scottish Gaelic for beginners

- Air Splaoid! Discover Gaelic with Dwelly, a free online Gaelic language course.

- BBC Learn Gaelic

- CLI Gàidhlig Gaelic supporters and learners organisation that produces the bilingual magazine Cothrom

- ELAcademy Gaelic language courses in Edinburgh.

- AmBaile.org - Home of Highland Gaelic culture Online games for Scottish Gaelic learners

- Akerbeltz - A’ Ghobhar Dhubh Gaelic Resources (grammar, pronunciation, rhymes, names ...)

- Scottish Gaelic at Omniglot

- Learners' material online

- BBC Can Seo - Gaelic for Beginners book and videos from the 1970s

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||