Duchy of Schleswig

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Schleswig or South Jutland (Danish: Sønderjylland or Slesvig; German: Schleswig; Low German: Sleswig; North Frisian: Slaswik or Sleesweg) is a region covering the area about 60 km north and 70 km south of the border between Germany and Denmark. The region is also known archaically in English as Sleswick.

The area's traditional significance lies in the transfer of goods between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, connecting the trade route through Russia with the trade routes along Rhine and the Atlantic coast (see also Kiel Canal).

Contents |

History

Roman sources place the homeland of the Jute tribe north of the river Eider and that of the Angles to its south who in turn abutted the neighboring Saxons. Towards the end of the Early Middle Ages, Schleswig formed part of the historical Lands of Denmark as Denmark unified out of a number of petty chiefdoms in the 8th to 10th centuries (The heyday of the Viking incursions).

During the early Viking Age, Haithabu - Scandinavia's biggest trading centre - was located in this region which is also the location of the Danewerk. This construction, and in particular its great expansion around 737 has been interpreted as an indication of the emergence of a unified Danish state.[1]

In May 1931 scientists of the National Museum of Denmark announced the finding of eighteen Viking graves with eighteen men in them. The discovery came during excavations in Schleswig. The skeletons indicated that the men were bigger proportioned than twentieth century Danish men. Each of the graves was turned east to west. It was surmised that the bodies were entombed in wooden coffins originally, but only the iron nails remained.[2]

During the 10th century, ownership over the region between the Eider River and the Danevirke became a matter of dispute between the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark, resulting in several wars. In 974, Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor concluded a successful campaign by erecting a fortress, which was however razed by Sweyn Forkbeard in 983.

|

Schleswig on Jutland.

|

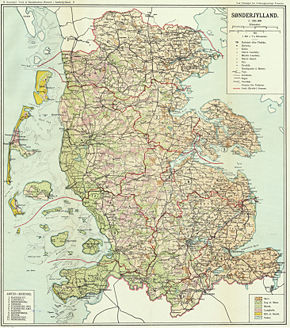

Schleswig prior to its partition (also encompassing Ribe as well as the Baltic islands of Fehmarn and Ærø, identified as 9a and 4b, respectively).

|

The contemporary transnational Euroregion Sønderjylland-Schleswig covers most of historical Schleswig.

|

High Middle Ages

In 1027, Conrad II and Canute the Great settled their mutual border at the Eider.[3] In 1115, king Niels created his nephew Canute Lavard - a son of his predecessor Eric I - Earl of Schleswig, a title used for only a short time before the recipient began to style himself Duke.[4] In 1230s, Southern Jutland (Duchy of Slesvig) was allotted as an appanage to Abel Valdemarsen, Canute's great-grandson, a younger son of Valdemar II of Denmark. Abel, having wrested the Danish throne to himself for a brief period, left his duchy to his sons and their successors, who pressed claims to the throne of Denmark for much of the next century, so that the Danish kings were at odds with their cousins, the dukes of Slesvig.

Early Modern Times

Feuds and marital alliances brought the Abel dynasty into a close connection with the German Duchy of Holstein by the 15th century. The latter was a fief subordinate to the Holy Roman Empire, while Schleswig remained a Danish fief. These dual loyalties were to become a main root of the dispute the between German states and Denmark in the 19th century, when the ideas of romantic nationalism and the nation-state won popular support. The title Duke of Schleswig was inherited in 1460 by the hereditary kings of Norway who also regularly were elected kings of Denmark simultaneously, and their sons (contrary to Denmark which was not hereditary). (This was an anomaly - a king holding a ducal title, which he as king was the fount of and its liege lord - the title and anomaly survived presumably because it was already co-regally held by the king's sons.)

19th century

Conflict between Denmark and German states over Schleswig and Holstein led to the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the 19th century. Denmark attempted to integrate the Duchy of Schleswig into the Danish kingdom in 1848, leading to an uprising of ethnic Germans who supported Schleswig's ties with Holstein. The Kingdom of Prussia, led by Otto von Bismarck, intervened and defeated Denmark in the resulting First War of Schleswig, but was forced to return Schleswig and Holstein under pressure from the Austrian and Russian Empires.

Denmark again attempted to integrate Schleswig in 1864, but the German Confederation defeated the Danes in the Second War of Schleswig. Prussia and Austria respectively assumed administration of Schleswig and Holstein under the Gastein Convention of 14 August 1865. However, tensions between the two powers culminated in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, in which victorious Prussia annexed Schleswig and Holstein, creating the province of Schleswig-Holstein.

Modern Times

Two referendums held in 1920 resulted in the partition of the region. Northern Schleswig joined Denmark, whereas Central Schleswig voted to remain a part of Germany. In Southern Schleswig no referendum was held as the likely outcome was apparent. The name Southern Schleswig is now used for all of German Schleswig.

Today, both parts cooperate as a Euroregion, despite the national frontier dividing the former duchy.

Dukes and rulers

Former naming dispute

In the 19th century, there was a naming dispute concerning the use of Schleswig or Slesvig and Sønderjylland (South Jutland).

Germans strongly objected to the Danish use of "Sønderjylland". "Olsen's Map", published by the Danish cartographer Olsen in the 1830s and using that term, aroused a storm of protests by German inhabitants. The name "Schleswig", which had a long previous history with no special political connotations, assumed a clear German nationalist character in the 19th century - especially when included in the combined term "Schleswig-Holstein". A central element of the German nationalistic claim was the insistence upon Schleswig and Holstein being a single, indivisible entity. Since Holstein was legally part of the German Confederation and ethnically entirely German with no Danish population, use of that name implied that both provinces should belong to Germany and their connection with Denmark weakened or altogether severed.

For their part, Danes had no objection to the use of "Schleswig" as such, and in fact the name had a commonly-used Danish version "Slesvig". "Sønderjylland" was an older term, hardly used between the 16th and 19th centuries. However, its revival and widespread use in the 19th Century had a clear Danish nationalist connotation of laying a claim to the territory and objecting to the German claims.

The naming dispute was resolved with the 1920 plebiscites and partition, each side applying its preferred name to the part of the territory remaining in its possession - though both terms can in principle still refer to the entire region. Northern Schleswig was after the 1920 plebiscites officially named South Jutlandic districts (de sønderjyske landsdele), while Southern Schleswig became a part of German Schleswig-Holstein.

See also

- Coat of arms of Schleswig

- Danevirke

- German Bight

- Jutland

- Hedeby

- History of Schleswig-Holstein

- North Frisian Islands

- Schleswig-Holstein Question

- Traditional districts of Denmark

References

- ↑ Michaelsen, Karsten Kjer, "Politikens bog om Danmarks oldtid", Politikens Forlag (1. bogklubudgave), 2002, 87-00-69328-6, pp. 122-123 (Danish)

- ↑ Viking Find Reported, New York Times, May 17, 1931, pg. 5.

- ↑ Meyers Konversationslexikon, 4th edition (1885-90), entry: "Eider" [1](German)

- ↑ Danmarkshistoriens hvornår skete det, Copenhagen: Politiken, 1966, p. 65 (Danish)