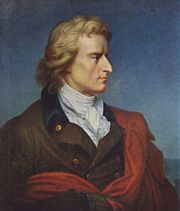

Friedrich Schiller

| Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 10 November 1759 Marbach am Neckar, Germany |

| Died | 9 May 1805 (aged 45) Weimar, Germany |

| Occupation | poet, dramatist |

| Nationality | German |

| Literary movement | Sturm und Drang, Weimar Classicism |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller [johan/joːhan krɪstɔf friːtʁɪç fɔn ʃɪləʁ/ʃɪlɐ] (10 November 1759 – 9 May 1805) was a German poet, philosopher, historian, and dramatist. During the last few years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller struck up a productive, if complicated, friendship with already famous and influential Johann Wolfgang Goethe, with whom he greatly discussed issues concerning aesthetics, encouraging Goethe to finish works he left merely as sketches; this thereby gave way to a period now referred to as Weimar Classicism. They also worked together on Die Xenien (The Xenies), a collection of short but harshly satirical poems in which both Schiller and Goethe verbally attacked those persons they perceived to be enemies of their aesthetic agenda.

Contents |

Biography

Schiller was born in Marbach, Württemberg (located at the river Neckar in southwest Germany, north of Stuttgart, the region of Swabia), as the only son, besides five sisters, of military doctor Johann Kaspar Schiller (1733–1796), and Elisabeth Dorothea Kodweiß (1732–1802). On 22 February 1790, he married Charlotte von Lengefeld (1766–1826). Four children were born between 1793 and 1804: the sons Karl and Ernst, and daughters Luise and Emilie. The last living descendent of Schiller was a grandchild of Emilie, Baron Alexander von Gleichen-Rußwurm, who died at Baden-Baden, Germany in 1947.

His father was away in the Seven Years' War when Friedrich was born. He was named after Frederick II of Prussia (Friedrich is German for Frederick), the king of the country his father was fighting, Prussia, but he was called Fritz by nearly everyone.[1] Kaspar Schiller was rarely home at the time, which was hard on his wife, but he did manage to visit the family once in a while and his wife and children also visited him occasionally wherever he happened to be stationed at the time.[2] In 1763, the war ended. Schiller's father became a recruiting officer and was stationed in Schwäbisch Gmünd. The family moved with him, of course; but since the cost of living especially the rent soon turned out to be too high, the family moved to nearby Lorch, which was at the time still a fairly small village.[3]

Although the family was happy in Lorch, Schiller's father found his work unsatisfying. He did, however, take young Friedrich with him occasionally.[4] In Lorch Schiller received his primary education, but the schoolmaster was lazy, so the quality of the lessons was fairly bad; therefore, Friedrich regularly cut class with his older sister.[5] Because his parents wanted Schiller to become a pastor himself, they had the pastor of the village instruct the boy in Latin and Greek. The man was a good teacher, which led Schiller to name the cleric in Die Räuber after Pastor Moser. Schiller was excited by the idea of becoming a cleric and often put on black robes and pretended to preach.[6]

In 1766, the family left Lorch for the Duke's principal residence, Ludwigsburg. Schiller's father had not been paid for three years and the family had been living on their savings, but could no longer afford to do so. So Kaspar Schiller had himself assigned to the garrison in Ludwigsburg. The move was not easy for Friedrich, since Lorch had been a warm and comforting home throughout his childhood.[7]

He came to the attention of Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg. He entered the Karlsschule Stuttgart (an elite, extremely strict, military academy founded by Duke Karl Eugen), in 1773, where he eventually studied medicine. During most of his short life, he suffered from illnesses that he tried to cure himself.

While at the Karlsschule, Schiller read Rousseau and Goethe and discussed Classical ideals with his classmates. At school, he wrote his first play, Die Räuber (The Robbers), which dramatizes the conflict between two aristocratic brothers: the elder, Karl Moor, leads a group of rebellious students into the Bohemian forest where they become Robin Hood-like bandits, while Franz Moor, the younger brother schemes to inherit his father's considerable estate. The play's critique of social corruption and its affirmation of proto-revolutionary republican ideals astounded the original audience, and made Schiller an overnight sensation. Later, Schiller would be made an honorary member of the French Republic because of this play.

In 1780, he obtained a post as regimental doctor in Stuttgart, a job he disliked.

Following the remarkable performance of Die Räuber in Mannheim, in 1781, he was arrested and forbidden by Karl Eugen himself from publishing any further works. He fled Stuttgart in 1783, coming via Leipzig and Dresden to Weimar, in 1787. In 1789, he was appointed professor of History and Philosophy in Jena, where he wrote only historical works. He returned to Weimar in 1799, where Goethe convinced him to return to playwriting. He and Goethe founded the Weimar Theater which became the leading theater in Germany, leading to a dramatic renaissance. He remained in Weimar, Saxe-Weimar until his death at 45 from tuberculosis.

The coffin containing Schiller's skeleton is in the Weimarer Fürstengruft[8] (Weimar's Ducal Vault), the burial place of Houses of Grand Dukes (großherzoglichen Hauses) of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in the Historical Cemetery of Weimar.[9] On 3 May 2008 it was announced that the DNA tests have shown that the skull of this skeleton is not Schiller's.[10] The similarity between this skull and the extant death-mask[11] as well as portraits of Schiller had led many experts to believe that the skull was Schiller's.

In September 2008, Schiller was elected by the audience of the Franco-german TV channel ARTE to be Europe's greatest playwright after William Shakespeare.

Freemasonry

Some Freemasons speculate that Schiller was a Freemason, but this has not been proven.[12]

In 1787, in his tenth letter about Don Carlos Schiller wrote:

- “I am neither Illuminati nor Mason, but if the fraternization has a moral purpose in common with one another, and if this purpose for the human society is the most important, ...”[13]

In a letter from 1829, two Freemasons from Rudolstadt complain about the dissolving of their Lodge Günther zum stehenden Löwen that was honoured by the initiation of Schiller. According to Schiller's great-grandson Alexander von Gleichen-Rußwurm, Schiller was brought to the Lodge by Wilhelm Heinrich Karl von Gleichen-Rußwurm, but no membership document exists.[13]

Writing

Philosophical papers

Schiller wrote many philosophical papers on ethics and aesthetics. He synthesized the thought of Immanuel Kant with the thought of Karl Leonhard Reinhold. He developed the concept of the Schöne Seele (beautiful soul), a human being whose emotions have been educated by his reason, so that Pflicht und Neigung (duty and inclination) are no longer in conflict with one another; thus "beauty," for Schiller, is not merely a sensual experience, but a moral one as well: the Good is the Beautiful. His philosophical work was also particularly concerned with the question of human freedom, a preoccupation which also guided his historical researches, such as the Thirty Years War and The Revolt of the Netherlands, and then found its way as well into his dramas (the "Wallenstein" trilogy concerns the Thirty Years War, while "Don Carlos" addresses the revolt of the Netherlands against Spain.) Schiller wrote two important essays on the question of the Sublime (das Erhabene), entitled "Vom Erhabenen" and "Über das Erhabene"; these essays address one aspect of human freedom as the ability to defy one's animal instincts, such as the drive for self-preservation, as in the case of someone who willingly dies for a beautiful idea.

The dramas

Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright. Critics like F.J. Lamport and Eric Auerbach have noted his innovative use of dramatic structure and his creation of new forms, such as the melodrama and the bourgeois tragedy. What follows is a brief, chronological description of the plays.

- The Robbers (Die Räuber): The language of The Robbers is highly emotional and the depiction of physical violence in the play marks it as a quintessential work of Germany's Romantic 'Storm and Stress' movement. The Robbers is considered by critics like Peter Brooks to be the first European melodrama. The play pits two brothers against each other in alternating scenes, as one quests for money and power, while the other attempts to create a revolutionary anarchy in the Bohemian Forest. The play strongly criticises the hypocrisies of class and religion and the economic inequities of German society; it also conducts a complicated inquiry into the nature of evil.

- Fiesco (Die Verschwörung des Fiesco zu Genua):

- Intrigue and Love (Kabale und Liebe): The aristocratic Ferdinand von Walter wishes to marry Luisa Miller, the bourgeois daughter of the city's music instructor. Court politics involving the duke's beautiful but conniving mistress, Lady Milford and Ferdinand's ruthless father create a disastrous situation reminiscent of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Schiller develops his criticisms of absolutism and bourgeois hypocrisy in this bourgeois tragedy. Act 2, Scene 2 is an anti-British parody that depicts a bloody firing-squad massacre, in which young Germans who refused to join the Hessian Army to quash the American Revolutionary Army are fired upon.[14] Giuseppe Verdi's opera Luisa Miller is based on this play.

- Don Carlos: This play marks Schiller's entrée into historical drama. Very loosely based on the events surrounding the real Don Carlos of Spain, Schiller's Don Carlos is another republican figure--he attempts to free Flanders from the despotic grip of his father, King Phillip. The Marquis Posa's famous speech to the king proclaims Schiller's belief in personal freedom and democracy.

- The Wallenstein Trilogy: These plays follow the fortunes of the treacherous commander Albrecht von Wallenstein during the Thirty Years' War.

- Mary Stuart (Maria Stuart): This "revisionist" history of the Scottish queen who was Elizabeth I's rival makes of Mary Stuart a tragic heroine, misunderstood, and used by ruthless politicians, including and especially, Elizabeth herself.

- The Maid of Orleans (Die Jungfrau von Orleans):

- The Bride of Messina (Die Braut von Messina):

- William Tell (Wilhelm Tell):

- Demetrius (unfinished):

The Aesthetic Letters

A pivotal work by Schiller was On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a series of Letters, (Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen in einer Reihe von Briefen) which was inspired by the great disenchantment Schiller felt about the French Revolution, its degeneration into violence and the failure of successive governments to put its ideals into practice.[15] Schiller wrote that "a great moment has found a little people," and wrote the Letters as a philosophical inquiry into what had gone wrong, and how to prevent such tragedies in the future. In the Letters he asserts that it is possible to elevate the moral character of a people, by first touching their souls with beauty, an idea that is also found in his poem Die Künstler (The Artists): "Only through Beauty's morning-gate, dost thou penetrate the land of knowledge."

On the philosophical side, Letters put forth the notion of der sinnliche Trieb / Sinnestrieb ("the sensuous drive") and Formtrieb ("the formal drive"). In a comment to Immanuel Kant's philosophy, Schiller transcends the dualism between Form and Sinn, with the notion of Spieltrieb ("the play drive") derived from, as are a number of other terms, Kant's The Critique of the Faculty of Judgment. The conflict between man's material, sensuous nature, and his capacity for reason (Formtrieb being the drive to impose conceptual and moral order on the world), Schiller resolves with the happy union of Form and Sinn, the "play drive," which for him is synonymous with artistic beauty, or "living form." On the basis of Spieltrieb, Schiller sketches in Letters a future ideal state (an eutopia), where everyone will be content, and everything will be beautiful, thanks to the free play of Spieltrieb. Schiller's focus on the dialectical interplay between Form and Sinn has enthused a wide range of succeeding aesthetic philosophical theory, including notably Jacques Ranciere's conception of the "aesthetic regime of art."

Ennoblement

For his achievements, Schiller was ennobled, in 1802, by the Duke of Weimar. His name changed from Johann Christoph Friedrich Schiller to Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller.

Quotations

- "Against stupidity the gods themselves contend in vain." – (Talbot in Maid of Orleans)

- "The voice of the majority is no proof of justice." (Sapieha, in: Demetrius)

- "Deeper meaning resides in the fairy tales told to me in my childhood than in any truth that is taught in life."

- "Eine Grenze hat die Tyrannenmacht", which literally means "A tyrant's power has a limit" - – Wilhelm Tell

- "It is not flesh and blood but the heart which makes us fathers and sons."

- "All men will be brothers" (included in the chorus of Beethoven's ninth symphony)

- "Live with your century but do not be its creature." (From On the Aesthetic Education of Man.)

Musical settings of Schiller's poems and stage plays

Ludwig van Beethoven said that a great poem is more difficult to set to music than a merely good one because the composer must improve upon the poem. In that regard, he said that Schiller's poems were greater than those of Goethe, and perhaps that is why there are relatively few famous musical settings of Schiller's poems. Two notable exceptions are Beethoven's setting of An die Freude (Ode to Joy)[14] in the final movement of the Ninth Symphony, and the choral setting of Nänie by Johannes Brahms. In addition, several poems were set by Franz Schubert in lieder, mostly for voice and piano.

Also, Giuseppe Verdi admired Schiller greatly and adapted several of his stage plays for his operas: I masnadieri is based on Die Räuber; Giovanna d'Arco, on Die Jungfrau von Orleans; Luisa Miller, on Kabale und Liebe; Don Carlos on the play of the same title. Donizetti's Maria Stuarda is based on Maria Stuart, and Rossini's Guillaume Tell is an adaptation of Wilhelm Tell.

Works

Plays

- Die Räuber (The Robbers), 1781

- Kabale und Liebe (Intrigue and Love),[14] 1784

- Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien (Don Carlos),[16] 1787

- Wallenstein,[17] 1800

- Die Jungfrau von Orleans (The Maid of Orleans), 1801

- Maria Stuart (Mary Stuart),[18] 1801

- Turandot, 1802

- Die Braut von Messina (The Bride of Messina), 1803

- Wilhelm Tell (William Tell), 1804

- Demetrius (unfinished at his death)

Histories

- Geschichte des Abfalls der vereinigten Niederlande von der spanischen Regierung or The Revolt of the Netherlands

- Geschichte des dreissigjährigen Kriegs or A History of the Thirty Years' War

- Über Völkerwanderung, Kreuzzüge und Mittelalter or On the Barbarian Invasions, Crusaders and Middle Ages

Translations

- Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis

- William Shakespeare, Macbeth

- Jean Racine, Phèdre

Prose

- Der Geisterseher or The Ghost-Seer (unfinished novel) (started in 1786 and published periodically. Published as book in 1789)

- Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen in einer Reihe von Briefen (On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a series of Letters), 1794

Poems

- An die Freude or Ode to Joy[14](1785) became the basis for the fourth movement of Beethoven's ninth symphony

- The Artists

- The Hostage which Schubert set to music

- The Cranes of Ibykus

- Song of the Bell

- Columbus

- Hope

- Pegasus in Harness

- The Glove

- Nänie which Brahms set to music

Notes and Citations

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 18

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 20

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 20-21

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 23

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 24

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 25

- ↑ Lahnstein 1981, pg. 27

- ↑ Weimarer Fürstengruft, German Wikipedia.

- ↑ Historischer Friedhof Weimar, German Wikipedia.

- ↑ Schädel in Schillers Sarg wurde ausgetauscht (Skull in Schiller's coffin is exchanged), Spiegel Online, Saturday 3 May 2008, [1].

Schädel in Weimar gehört nicht Schiller (Skull in Weimar does not belong to Schiller), Welt Online, Saturday 3 May 2008, [2]. - ↑ Death Mask

- ↑ Friedrich Von Schiller

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Eugen Lennhoff, Oskar Posner, Dieter A. Binder: Internationales Freimaurer Lexikon. Herbig publishing, 2006, ISBN 978-3-7766-2478-6

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Schiller was an icon of the Revolution of 1848 to Europeans as he was earlier during the American Revolution (7000 Hessians defected permanently to the US during that war and many thousands of Germans followed later when the Revolutions of 1848 were quashed and one despot after another ruled in Europe) with his numerous anti Hessian/British plays and poems, including The Robbers (1781) and Intrigue and Love (1784) (SEE Act 2, Scene 2, that describes that massacre of young German-Hessians for refusing to fight the Americans) and, just months after that later revolutionary play, Schiller's heavily censored 'Declaration of Independence' poem, “To the Happiness” (The correct translation is "Happiness", not "Joy", since it refers to the concept expressed in “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”), poetry that Beethoven later set to the last, choral movement of his 9th Symphony.

Schiller also had a copy of an engraving version of the "Battle of Bunker Hill", original 1786 oil, by John Trumbull, that he hung in his living room in Weimar and is probably still there. (SEE The Autobiography of Col. John Trumbull, Sizer 1953 ed., pg.184,n.13) - ↑ Shiller, On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Ed. Wilinson and Willoughby, 1967 (OED)

- ↑ Mike Poulton translated this play in 2004.

- ↑ Wallenstein was translated from a manuscript copy into English as The Piccolomini and Death of Wallenstein by Coleridge in 1800.

- ↑ Mike Poulton translated this play in 2054.

Bibliography

- Lahnstein, Peter (January 1984) [1981]. Schillers Leben. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer. ISBN 3-596-25621-6.

Schiller's complete works are published in the following excellent editions:

- historical-critical edition by K. Goedeke (17 volumes, Stuttgart, 1867-76); Säkular-Ausgabe edition by Von der Hellen (16 volumes, Stuttgart, 1904-05); historical-critical edition by Günther and Witkowski (20 volumes, Leipzig, 1909-10). Other valuable editions are: the Hempel edition (1868-74); the Boxberger edition, in Kürschners National-Literatur (12 volumes, Berlin, 1882-91); the edition by Kutscher and Zisseler (15 parts, Berlin, 1908); the Horenausgabe (16 volumes, Munich, 1910, et. seq.); the edition of the Tempel Klassiker (13 volumes, Leipzig, 1910-11); and that in the Helios Klassiker (6 volumes, Leipzig, 1911). Documents and other memorials of Schiller are in the Schiller Archiv, united in 1889 with the Goethe Archiv in Weimar.[3]

See also

- Physician writer

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Weimar Classicism

- Carleton College

External links

- Works by Friedrich Schiller at Project Gutenberg

- Friedrich Schiller Chronology

- 2005 is Schiller year: all dates

- Letters upon the Education of Man at [4]

- Letters Upon The Aesthetic Education of Man in PDF Format at filepedia.org

- Schiller Monument in Schiller Park, German Village, Columbus, Ohio, USA

- Schiller multimedial combines a biographical observation by Norbert Oellers with classic recordings and video clips

- Mobile Schiller Mobile Java application containing 20 poems of Schiller

- Say it loud – it's Schiller and it's proud What relevance does Schiller have today? By George Steiner at signandsight.com

- A small crater on the surface of the moon, named after Schiller

- Friedrich-Schiller University of Jena

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Schiller, Friedrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | German poet, philosopher, historian, and dramatist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 10 November 1759 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Marbach, Württemberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | 9 May 1805 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Weimar, Saxe-Weimar |