Schengen Agreement

|

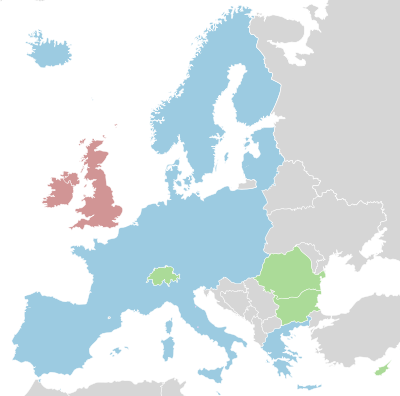

Implementation Schengen zone

Set to implement later

Police and judicial cooperation only

Expressed interest

|

The term Schengen Agreement is used for two agreements concluded among European states in 1985 and 1990 which deal with the abolition of systematic border controls among the participating countries. By the Treaty of Amsterdam, the two agreements themselves and all decisions that have been enacted on their basis have been incorporated into the law of the European Union. This body of legal provisions is referred to as the Schengen Acquis.[1] Subsequent amendments to that acquis, including the Schengen Agreements themselves, have been made in the form of European Union regulations. The main purpose of the establishment of the Schengen rules is the abolition of physical borders among European countries.[2] The Schengen rules apply among most European countries, covering a population of over 400 million and a total area of 4,268,633 km2 (1,648,128 sq mi). They include provisions on common policy on the temporary entry of persons (including the Schengen Visa), the harmonisation of external border controls, which are coordinated by the Frontex agency of the European Union, and cross-border police and judicial co-operation. A total of 25 states, 22 from the European Union states 3 non-EU members (Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein), have a full set of rules in the Schengen Agreement (as amended), and implemented its provisions so far.

At the time of the implementation of the Schengen acquis into EU law, Ireland and the United Kingdom were only EU members that did not sign up to the original Schengen Convention of 1990, and retained a right to opt out of the application of the rules after their conversion into European Union law. Thus, they have not ended border controls with other EU Member States, but do apply the provisions relating to police and judicial co-operation which form part of the Schengen acquis. Border posts and checks were removed between states in the Schengen area.[3] A common Schengen visa allows tourists or other visitors access to the area. Holders of residence permits to a Schengen state enjoy the freedom of travel to other Schengen states for a period of up to three months.

The agreements were named after the small town of Schengen in Luxembourg, near which they were signed.[4]

Legal basis of the Schengen rules

Provisions in the treaties of the European Union

The legal basis for Schengen in the treaties of the European Union has been inserted in the Treaty establishing the European Community through Article 2, point 15 of the Treaty of Amsterdam. This inserted a new title named "Visas, asylum, immigration and other policies related to free movement of persons" into the treaty, currently numbered as Title IV, and comprising articles 61 to 69.[5][6] The Treaty of Lisbon substantially amends the provisions of the articles in the title, renames the title to "Area of freedom, security and justice" and divides it into five chapters, called "General provisions", "Policies on border checks, asylum and immigration", "Judicial cooperation in civil matters", "Judicial cooperation in criminal matters", and "Police cooperation".[7]

Two Schengen agreements

The two agreements which are commonly referred to as Schengen Agreement are:

- The 1985 Agreement between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders,[8] also known as Schengen I, which provided for simple visual surveillance of private vehicles crossing the common border at reduced speed, without requiring such vehicles to stop. Persons who did not have to meet specific requirements at internal borders, as, for example, visa requirements, could use this fast lane procedure by affixing to the windscreen a green disc measuring at least eight centimetres in diameter.

- The 1990 Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 1985 between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders,[9] also known as Schengen II or CIS.

These two agreements have been republished in the Official Journal of the European Communities through the Council decision concerning the definition of the Schengen acquis[1] and form the most important part of the secondary legislation regarding Schengen of the EU.

European Union Regulations

Other relevant legal texts which form part of the Schengen laws include:

- The Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code),[10] repealing the parts of the Convention Implementing the Schengen Agreement, dealing in detail with border controls and the prerequisites for entry by third-country nationals;

- The Council Regulation (EC) No 539/2001,[11] dealing with the visa requirement for short stays in the Schengen area according to nationality;

- The Council Regulation (EC) No 693/2003,[12] which deals with the transit from the main part of Russia to the Kaliningrad area;

- The Common Consular Instructions on Visas for the Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts,[13] which contains rules of procedure for the issuance of visa;

- The Council Regulation (EC) No 1683/95 of 29 May 1995 laying down a uniform format for visas;[14]

- The Regulation (EC) No 1987/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on the establishment, operation and use of the second generation Schengen Information System (SIS II), governing the introduction of the second generation of the Schengen Information System.[15]

- The Council Regulation (EC) No 343/2003, dealing with the question which member state is responsible to handle an asylum request lodged by a third-country national,[16] also referred to as Dublin II;

- The Commission Regulation (EC) No 1560/2003,[17] setting out detailed procedures for the application of the Dublin II regulation.

Legislators of Schengen rules

The amended Treaty establishing a European Community specified that during a five year transitional period following the entry into force of the Treaty of Amsterdam (May 1, 1999) the Council could adopt Schengen rules only unanimously after a proposal from the European Commission or on the initiative of a Member State. The European Parliament was only to be consulted.[6]

After this five year transitional period, the Council would make a unanimous decision to legislate in the future certain or all Schengen rules under the codecision procedure, which gives the European Parliament equal power to the Council. The Council did so with the Council Decision of 22 December 2004 providing for certain areas covered by Title IV of Part Three of the Treaty establishing the European Community to be governed by the procedure laid down in Article 251 of that Treaty.[18] As from January 1, 2005, virtually all Schengen rules are thus legislated by both the Parliament and the Council.

Rules concerning border controls

Travel without internal border controls

Before the implementation of the Schengen II Agreement, citizens of western Europe could travel to neighbouring countries by showing their national ID card or passport at the border. Nationals of some countries were required to have separate visas for every country in Europe; thus, a vast network of border posts existed around the continent which disrupted traffic and trade—causing delays and costs to both businesses and visitors.

Since the implementation of the Schengen rules, border posts have been closed (and often demolished) between participating countries. The Schengen Borders Code requires participating states to remove all obstacles to free traffic flow at internal borders.[19] Thus, road traffic is no longer delayed; road, rail and air passengers no longer have their identity checked by border guards when crossing borders (however, security controls by carriers are still permissible).[20] Citizens of non-EU, non-EEA countries who wish to visit Europe, and who require a visa to enter the Schengen area, receive a common Schengen Visa from the Embassy or Consulate of the Schengen country of their main destination, or, if such main destination cannot be identified, the state they intend to visit first; they may then visit any of the Schengen countries without hindrance. However, in some exceptional cases, visas can be restricted to just certain member states.

Regulation of external border controls

Not only does the Schengen Agreement remove border checks between participating countries, but the external controls which are exercised by the participating nations are also co-ordinated by the European Union's Frontex agency, and subject to common rules. The details of border controls, surveillance, and the conditions under which permission to enter into the Schengen area may be granted are exhaustively detailed in a European Union regulation called Schengen Borders Code.[21] In particular, Article 7 of the Schengen Borders Code provides that all persons crossing external borders — inbound or outbound — have to be subject to a minimum check, this including the establishment of identities on the basis of the production or presentation of their travel documents, while third-country nationals must be subjected to thorough checks, which also concern all entry requirements (documentation, visa, employment status, means of subsistence, absence of security concerns). The exit controls allow, inter alia, to determine if a person leaving the area is in possession of a document valid for crossing the border, whether that person had extended his or her stay beyond the permitted period, and to check against alerts on persons and objects included in the Schengen Information System and reports in national data files, e. g. if an arrest warrant had been issued by a Schengen State.[22]

The borders against non-Schengen countries are to be carefully controlled, and every person crossing those external borders must carry an accepted means of identification, such as a passport, other travel document, or – in case of EU and Swiss citizens – national identity card.[23] All persons who are third-country nationals have to be checked against the Schengen Information System, a database containing information about undesired or wanted people, stolen passports, and other items of interest to border officials;[24] while checks on EU citizens and other persons enjoying the right of free movement in the EU may only be conducted on a "non-systematic" basis.[25]

The border controls are located at roads crossing a border, at airports, at seaports, and onboard trains.[26] Usually there is no fence along borders in the terrain, but there are exceptions like the Ceuta border fence. However, surveillance camera systems, also equipped infrared technology, are located at some more critical spots, for example at the border between Slovakia and Ukraine.[27] Along the southern coast of the Schengen countries, coast guards are making a substantial effort to prevent private boats from entering without permission.

The Schengen law stipulates that all transporters of passengers across the Schengen external border must check, before boarding, if the passenger has the travel document and visa required for entry.[28] This is to prevent persons from applying for asylum at the passport control, after already having landed within the Schengen area. Since all asylum applications filed on EU territory must be investigated, and since it often proves to be difficult to deport persons who already have landed, the Schengen states want to prevent third-country nationals who do not have the papers required for entry into the area from even reaching a passport control point on their territory. Because this system proves to be effective, unsafe boats, containers, or other unconventional and life-endangering means of transport are used for people smuggling.

Entry conditions for third-country nationals

The Schengen rules include uniform rules as to the type of visas which may be issued for a short-term stay, not exceeding 90 days, on the territory of one, several or all of those States. The rules also include common requirements for entry into the Schengen area, and common procedures for refusal of entry.

According to the Schengen Borders Code, the conditions applying to third-country nationals for entry are as follows:[29]

- The third-country national is in possession of a valid travel document or documents authorising them to cross the border; the acceptance of travel documents for this purpose remains within the domain of the member states;[30]

- He or she either possesses a valid visa (if required) or a valid residence permit;

- He or she can justify the purpose and conditions of the intended stay, and they have sufficient means of subsistence, both for the duration of the intended stay and for the return to their country of origin or transit to a third country into which they are certain to be admitted, or are in a position to acquire such means lawfully;

- There has not been issued an alert in the Schengen Information System for refusal of entry, and

- he or she is not considered to be a threat to public policy, internal security, public health or the international relations of any of the Schengen states.

In other words, mere possession of a Schengen visa does not confer automatic right of entry. It will only be granted if the other transit or entry conditions laid down by EU legislation have been met, notably the means of subsistence that aliens must have at their disposal, as well as the purpose and the conditions of the stay.

Right of stay

A third-country national who has been granted entry may stay in the Schengen area and travel between Schengen states as long as the conditions for entry are still fulfilled.[31] For stays which exceed three months, so-called national visa (category D) are issued by the relevant Schengen state where the third-country national intends to reside. Any third-country national who is a holder of a residence permit of a Schengen state, which is granted for a stay which exceeds three months, is allowed to travel to any other member state for a period of up to three months.[32]

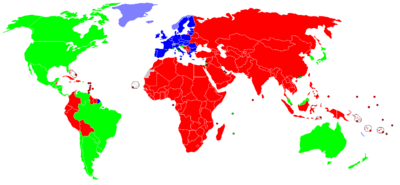

Schengen visa

The requirement of a visa for short-term stays in the Schengen area which do not involve employment or any self-employed activity are set out in an EU regulation.[33] The list of the nationals which require a visa for a short-term stay (so-called Annex I list) and the visa-free nationals (so-called Annex II list) refers to the nationality of the third-country national and not to the passport or travel document he or she is holding (with an exception to holders of Hong Kong SAR and Macau SAR passport holders, and another exception vis a vis holders of refugee travel documents, where the country which issued the travel document is relevant). Third-country nationals who intend to take up employment or self-employed activity may be required by member states to obtain a visa even if they are listed on the Schengen visa-free list; usual business trips are normally not considered employment in this sense.[34]

The uniform visa is granted in the form of a sticker affixed by a Member State onto a passport, travel document or another valid document which entitles the holder to cross the border, provided that the entry conditions are met at the time of entry.

It is granted in the following categories:[35]

- Category A refers to an airport transit visa. It is required for some few nationals for passing through the international transit area of airports during a stop-over or transfer between two sections of an international flight. The requirement to have this visa is an exception to the general right to transit without a visa through an international transit area of an airport.

- Category B refers to a transit visa. It is required by nationals who are not visa-free for travelling from one non-Schengen state to another non-Schengen state, in order to pass through the Schengen area. Each transit may not exceed five days.

- Category C refers to a short-term stay visa. They are issued for reasons other than to immigrate. They entitle holders to carry out a continuous visit or several visits whose duration does not exceed three months in any half-year from the date of first entry.

- Category D refers to national visa. They are issued by a Schengen state in accordance with its national legislation as with respect to the conditions (however, a uniform sticker is used). The national visa allows the holder to transit from a non-Schengen country to the Schengen state which issued the national visa within five days. Only after the holder has obtained a residence title after arrival in the destination country (or a different visa), he may again travel to other Schengen countries.

- Category D+C visa combine the functions of the visa of both categories: They are intended to allow the holder to enter the issuing Schengen state for long-term stay in that state, but also to travel in the Schengen area like a holder of a Category C visa.

- FTD and FRTD are special visa issued for road (FTD) or rail (FRTD) transit only between mainland Russian Federation and its western exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast.

Under specific circumstances, the territorial validitiy of a Schengen visa of the categories B, C, or D+C is issued with territorial validity to not all of the Schengen states. Such visa may, for example, be issued for humanitarian or other specific reasons. Territorial validity may also be restricted in case that the travel document in which it is affixed is not accepted by all of the Schengen states. In such cases, the visa authorises a foreigner entry, stay, and exit exclusively in the territory of one or more Schengen member states for which the visa is valid.

Under certain conditions, seamen are issued visa at the border in order to board a ship or travel home from a ship in a Schengen harbor. Furthermore, visa may also be issued at the border in exceptional cases, e.g. emergencies.[36]

To obtain a Schengen visa, a traveller must take the following steps:

- He or she must first identify which Schengen country is the main destination. This determines the State responsible for deciding on the Schengen visa application and therefore the embassy or the consulate where the traveller will have to lodge the application.[37] If the main destination cannot be determined, the traveller should file the visa application at the embassy or consultate of the Schengen country of first entry.[38][39] If the Schengen State of the main destination or first entry does not have a diplomatic mission or consular post in his country, the traveller must contact the embassy or the consulate of another Schengen country, normally located in the traveller's country, which represents, for the purpose of issuing Schengen visas, the country of the principal destination or first entry.

- The traveller must then present the Schengen visa application to the responsible embassy or consulate. A harmonised form is to be submitted, together with a valid passport and, if necessary, the documents supporting the purpose and conditions of the stay in the Schengen area (aim of the visit, duration of the stay, lodging). The traveller will also have to prove his or her means of subsistence, i.e., the funds available to cover, on the one hand, the expenses of the stay, taking into account its duration and the destination, and, on the other hand, the cost of the return to the home country. Certain embassies or consulates sometimes call the applicant to appear in person in order to explain verbally the reasons for the visa application.

- Finally, the traveller must have travel insurance that covers, for a minimum of €30,000, any expenses incurred as a result of emergency medical treatment or repatriation for health reasons. The proof of the travel insurance must in principle be provided at the end of the procedure, i.e. when the decision to grant the Schengen visa has already been made. This type of insurance can be easily found on the web from well-known insurers.

Requirements for family members of an EEA citizen differ from those indicated above. In general for family members of an EEA citizen, there is no requirement to provide information about one's employment, or to prove one's means of subsistence. In addition, no fee is required for the visa to be issued.

Internal movement of holders of a residence title

Third-country nationals who are holders of a residence title of a Schengen state may freely enter into and stay in any other Schengen state for a period of up to three months.[40] For a longer stay, they require a residence title of the target member state. Third-country long-term residents of a member state enjoy, under certain circumstances, the right to settle in other member states.[41].

The right of entry without additional visa was extended to the non-EEA family members of EEA nationals exercising their treaty right of free movement who hold a valid residence card or residence permit of their EEA host country and wish to visit any other EEA member state for a short stay up to 90 days[42][43][44]. This is implied in Directive 2004/38/EC, Article 5(2) provided that they travel together with the EEA national or join their spouse/partner at a later date (Article 6(2)). Several member countries (as at November 2008), however, do not follow the Directive in this respect[45][46] to the effect that non-EEA family members living in non-Schengen EU countries may still face difficulties (denial of boarding the vessel by the transport company, denial to enter by border police) when travelling to certain Schengen countries with their residence permit alone. Likewise non-Schengen member EU countries may deny entry to Schengen residence permit holders without an additional visa.

Local border traffic at external borders

Schengen States which share an external land border with a non-Schengen country are authorized by virtue of an EU regulation to conclude or maintain bilateral Agreements with neighbouring third countries for the purpose of implementing a local border traffic regime.[47] The regulation stipulates the conditions which have to be met by such agreements. The agreements have to provide for the introduction of a local border traffic permit under the relevant scheme. Such permits must contain the name and a picture of the holder, as well as a statement that its holder is not authorised to move outside the border area and that any abuse shall be subject to penalties. The border area may include any administrative district within 30 kilometres from the external border (and, if any district extends beyond that limit, the whole district up to 50 kilometres from the border).

Holders of such permit may cross the external borders, once there has not been issued an alert in the Schengen Information System for refusal of entry, and they do not form a threat to public policy, internal security, public health or the international relations of any of the Member States. The question whether an additional identity document is required for crossing the border (and which type may be used), and for how long the permit holder may stay in the border area, may be regulated bilaterally. The maximum permitted period of stay may not exceed three months. The features of the form of the permit have to comply with the uniform format for residence permits for third-country nationals. Permits are valid from one up to five years.

Permits may only be issued to persons having been lawful residents in the border area of a country neighbouring a Schengen State for a period specified in the relevant bilateral agreement, which generally has to be at least one year. The applicant for the permit has to show legitimate reasons frequently to cross an external land border under the local border traffic regime, and must meet the specific entry requirements as described above. Schengen states must keep a central register of the permits issued and have to provide immediate access to the relevant data to other Schengen states.

Before the conclusion of an agreement with a neighboring country, the Schengen state must receive approval from the European Commission, which has to confirm the legality of its draft. The agreement may only be concluded if the neighbouring country grants at least reciprocal rights to the relevant Schengen state, and readmission of illegally staying persons from the neighbouring country is ensured. For local border traffic, fast lanes or special border crossings may be introduced.

Special arrangement on entry for Croatians

There is an exception to these rules in the case of citizens of Croatia. Based on the Pre-Schengen bilateral agreements between Croatia and its neighboring EU countries (Italy, Hungary and Slovenia), Croatian citizens are allowed to cross the border with ID card only (passport not obligatory).[48] Many people living near the border cross it several times a day (some work across the border, or have land on the other side of the border), especially on the border with Slovenia, which was unmarked for centuries as Croatia and Slovenia were both part of Habsburg Empire (1527–1918) and Yugoslavia (1918–1991). As Croatia is expected to join EU in a matter of years, an interim solution, which received permission from the European Commission, was found: every Croatian citizen is allowed to cross the Schengen border into Hungary, Italy or Slovenia with an ID card and an evidention card that is issued by Croatian police at border exit control. Police authorities of Hungary, Italy or Slovenia will then stamp the evidention card both on entry and on exit. Croatian citizens, however, are not allowed to enter any other Schengen agreement countries without a valid passport and entry stamp, though they are allowed to travel between Hungary, Italy and Slovenia. This practice will be abandoned once Croatia becomes an EU member state, which will allow its citizens to enter any member country with an ID card only.

The Western Balkan states

Visa free regime negotiations between the EU and the Western Balkans were launched in the first half of 2008, and are currently underway.[49][50][51] The Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Serbia) already enjoy a facilitated visa regime with the Schengen states (UK and Ireland excluded), including shorter waiting periods, free or low visa fees, and fewer documentation requirements when compared to other countries whose citizens require C, D, or C+D visas. The visa free negotiations are being conducted on an individual basis, and roadmaps with a list of conditions to be fulfilled have been customized for each Western Balkan state. These negotiations can be concluded as early as the first half of 2009, and soon after that Western Balkan citizens will be able to enter the Schengen area without a visa.[52]. This must be in effect before Croatia joins the Schengen area, particularly since Bosnia-Herzegovina's Neum area separates Croatian coast in two, requiring two border checks on the trip from the Croatian cities of, e.g., Split and Dubrovnik.

Temporary reintroduction of internal border controls

A Schengen state is permitted by articles 23 to 31 of the Schengen Borders Code to reinstate border controls for a short period if deemed in the interest of national security, but has to follow a consultation procedure before such action. This occurred in Portugal during the 2004 European Football Championship and in France for the ceremonies marking the 60th anniversary of D-Day. Spain temporally reinstated border controls during the wedding of Crown Prince Felipe in 2004. It was used again by France shortly after the London bombings in July 2005. Finland briefly reinstated border controls during the 2005 World Championships in Athletics in August 2005. Germany used it for the 2006 FIFA World Cup and again in 2007 for the 33rd G8 summit in Heiligendamm. Austria used it for the UEFA Euro2008 in June 2008.

Air security

When travelling by air between Schengen countries or within a single Schengen country, identification (usually passport or national ID card) is often requested at the departure gate to allow airlines to board the correct passenger, in relation to the boarding card. Immigration control is not applied at point of departure or arrival (essentially, the flight is classed as 'domestic'). This means that visas are not checked in a formal way.

ID checks at hotels and other places

According to the Schengen rules, hotels and other types of commercial accommodation must register all foreign citizens, including citizens of other Schengen states, by requiring the filling of a registration form with their own hand. This does not apply to accompanying spouses and minor children or members of travel groups. In addition, a valid identification document has to be produced to the hotel manager or staff.[53] The Schengen rules do not provide further standards, thus, the Schengen states are free to regulate further details on the content of the registration forms, and the identity documents which are acceptable for identification, and may also require the persons exempted from registration by Schengen laws to be registered. Enforcement of these rules varies by country.

Customs control

While border controls serve the purpose of checking whether a person meets the entry and exit requirements, a customs border control relates to the goods that are transported across a border. While the EU (and preceding Communities) always enjoyed the exclusive competence of regulating customs procedures, the Schengen II Convention was originally drafted as an international treaty outside the scope of the EU. Thus, the contracting states had to find a solution for the abolishment of customs controls without being competent for regulating this matter. To this end, Article 120 of the Schengen II Convention provided (and still provides) that the contracting parties had to ensure that controls of goods "do not unjustifiably impede the movement of goods at internal borders". The parties had to facilitate the movement of goods across internal borders by providing for clearance of goods when goods were cleared through customs for home use. Although the clearance could, according to the Convention, be conducted either within the country or at the internal borders, the Schengen states had to encourage customs clearance within their respective territories. As far as such simplifications could not be achieved, the Schengen states bound themselves to agree on an alteration of existing rules either amongst themselves or within the framework of the European Community.[54]

Nowadays, the European Union has abolished not only customs controls, but also other procedures for the administrative processing of goods at internal borders, e.g. for internal taxation, leaving no checks at the borders between EU states.

At borders between the European Union Value Added Tax Area and those zones of the EU that lie outside it, the presence of customs authorities is permitted. Customs are also present in connection with travel within one single member state, if a part of that state is located outside the EU common customs area; this e.g. between Heligoland and mainland Germany. However, the presence of customs authorities at such borders would not mean that persons and goods passing the borders may be checked beyond the scope of spot checks, or on the basis of available intelligence, and such checks have to be non-systematic in order to comply with the Schengen Borders Code.

With respect to travel between EU members where one is non-Schengen, there are identity (passport) checks, but no customs checks; this applies, for instance, between Ireland or the U.K. and mainland Europe.

Since the customs forces form the financial police of a state, some countries allow their customs authorities to conduct routine inland checks on persons, vehicles, and goods, e.g., to detect untaxed goods, illegal workers, or persons abusing social benefits.

Norway and Iceland

There are two states that have fully implemented the Schengen agreements but are not EU states, namely Norway and Iceland. Even though they belong to the European Economic Area, some administrative handling of goods imported from the EU may still be required at their borders. Private persons are only allowed to bring small amounts of goods and alcohol over the border tax-free. (Within the EU, any amount of goods and alcohol meant for personal use may be taken across borders tax-free.)

Thus, the original provisions of the Schengen II Convention which regulate controls of goods originally could not be — and were not — set into force with relation to Norway and Iceland.[55]

However, the Schengen Borders Code, which became law after the association of Norway and Iceland, now provides that any police measures at the border may not "have an effect equivalent to border checks". Checks are, inter alia, permitted when they do not have border control as an objective, are based on general police information and experience regarding possible threats, are devised and executed in a manner clearly distinct from systematic checks on persons at the external borders, or if they are carried out on the basis of spot-checks.[56] Since a border check is defined as any check carried out at border crossing point, to ensure that persons, including their means of transport and the objects in their possession, may be authorised to enter or leave the territory,[57] routine custom controls are not permissible at internal Schengen borders. The Schengen Borders Code does not provide for any exemption of its scope of application in relation to Norway and Iceland, and is expressly applicable to those two countries.

Notwithstanding this, the authorities of Iceland are of the opinion that they may enforce the same level of customs procedures towards all travellers entering and leaving the country, as the country is not a part of the EU customs union.[58]

Sweden and Finland

Sweden and Finland, members of the EU and of the Schengen area, still maintain some customs checks in order to control the smuggling of drugs and alcohol. In accordance with the Schengen Borders Code, this is permissible, as long as cars are only stopped when a suspicion of smuggling has been established.[59] However, since vehicles have to stop at the toll plaza at the Swedish end of the Oresund Bridge from Copenhagen, cars are able to be checked and drivers questioned by the customs officials at will.

Switzerland and Liechtenstein

Switzerland, which belongs neither to the EU nor to the European Economic Area, has been associated to the Schengen area and is set to implement the Schengen rules, together with Liechtenstein, by December 12th 2008.[60] Similarly to the arrangements made between the EU, Norway, and Iceland, the accession agreement concluded between the EU and Switzerland provides for an exemption of the application of the rules concerning controls of goods at borders.[61] However, the much stricter provisions in the Schengen Borders Code providing for the abolition of internal border checks do not contain any exemption with respect to Switzerland. The Swiss authorities are of the opinion that they will not be entitled to perform systematic customs or other checks on persons for the mere reason that they cross the border, once the Schengen rules have been implemented in Switzerland; they are planning to continue to perform spot-checks, which are based on risk analysis of the authorities.[62]

Liechtenstein signed a Schengen-related association with the European Union on 28 February 2008[63] [64]. Unlike Switzerland, Liechtenstein belongs to the European Economic Area. The country also has an open border with Switzerland, but for the time being still conducts border checks on its border with Austria, an EU member, which are staffed by Swiss authorities.

For Switzerland, its open border with Liechtenstein had been an important issue. If it would not have been possible for Liechtenstein to implement the Schengen rules at the same time as Switzerland (as some EU states want to use the Schengen enlargement to pressure Liechtenstein over fraud issues), an interim solution would have had to be found, in order to avoid Switzerland introducing border checks with Liechtenstein, even for a short time.[65]

Rules concerning police co-operation

The Schengen rules also include provisions for sharing intelligence, such as information about people, lost and stolen documents, vehicles, via the Schengen Information System. This means that potentially problematic persons cannot 'disappear' simply by moving from one Schengen country to another.

Administrative Assistance

According to Article 39 of the Schengen II Convention, police administrations of the Schengen States are required to grant each other administrative assistance in the course of the prevention and detection of criminal offences according to the relevant national laws and within the scope of their relevant powers. They may cooperate through central bodies or, in case of urgency, also directly with each other. The Schengen provisions entitle the competent ministries of the Schengen States to agree on other forms of cooperation in border regions.

With respect to actions which imply constraint or the presence of police officers of a Schengen State in another Schengen State, specific rules apply.

Cross-border observation

Under Article 40 of the Schengen II Convention, police observation may be continued across a border if the person observed is presumed to have participated in an extraditable criminal offence. Prior authorization of the second state is required, except if the offence is a felony as defined in Article 40 (7) of the Schengen II Convention, and if urgency requires the continuation of the observation without prior consent of the second state. In the latter case, the authorities of the second state must be informed before the end of the observation in its territory, the request for consent has to be handed over as soon as possible, and the observation has to be terminated on request of the second state, or if consent has not been granted after five hours. The police officers of the first state are bound to the police laws of the second state, must carry identification which shows that they are police officers, and are entitled to carry their service weapons. They may not stop or arrest the observed persons, and must report to the second state after the operation has been finished. On the other hand, the second state is obliged to assist the enquiry subsequent to the operation, including judicial proceedings.

Hot pursuit

Under Article 41 of the Schengen II Convention, police from one Schengen state may cross national borders to chase their target, if it is not possible to notify the police of the second state prior to entry into that territory, or if the authorities of the second state are unable to reach the scene in time to take over the pursuit. The Schengen States may declare if they restrict the right to hot pursuit into their territory in time or in distance, and if they allow the neighboring states to arrest persons on their territory. However, the second state is obliged to challenge the pursued person in order to establish the person's identity or to make an arrest if so requested by the pursuing state. The right to hot pursuit is limited to land borders. The pursuing officers either have to be in uniform, or their vehicles have to be marked. They are permitted to carry service weapons, which may be used only in self-defence. After the operation, the first state has to report to the second state about its outcome.

Responsibility and rights

Under Article 42 of the Schengen II Convention, police officers of a state which became victims of a criminal offence in another Schengen state while on duty there, enjoy the same right of compensation as an officer of the second state. According to Article 43 of the Schengen II Convention, the state which employs a police officer is liable towards that state for damages for illegal actions performed in another state by such police officer.

Liaison officers

Article 47 of the Schengen II agreement provides for the permanent deployment of liaison officers to other Schengen states.

Further bilateral measures

Many neighboring Schengen states have introduced further bilateral measures for police cooperation in border regions, which are expressly permitted under Article 39 subsection 5 of the Schengen Agreement. Such cooperation may include joint police radio frequencies, police control centres, and tracing units in border regions.[66] Furthermore, police laws of some Schengen States allow for the ad hoc conferment of police powers to police officers of other EU states.[67]

Prüm Convention and Schengen III Regulation

An agreement was signed on 27 May 2005 by Germany, Spain, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Austria, and Belgium at Prüm, Germany. This agreement, based on the principle of availability which began to be discussed after the Madrid bomb attack on 11 March 2004, could enable them to exchange all data regarding DNA, fingerprint and Vehicle Registration Data of concerned persons and to cooperate against terrorism. Furthermore, it contains provisions for the deployment of armed sky marshals on intra-Schengen flights, joint police patrols, entry of (armed) police forces into the territory of another state for the prevention of immediate danger, cooperation in case of mass events or disasters. Furthermore, the police officer responsible for an operation in a state may, in principle, decide inhowfar the police forces of the other states which take part in the operation may use their weapons or exercise other police powers. Sometimes known as the Prüm Convention, this treaty is becoming known as the Schengen III Agreement. Certain (non-Schengen / 3rd pillar) provisions were adopted into EU law for all EU states Members in June 2008, as Council Decision with its provisions falling under the third pillar of the EU.[68] With respect to subject matters which are to be regulated within the first pillar of the EU, the implementation would require an initiative from the European Commission, which enjoys the monopoly (except the Member States) on legislative initiative in that pillar. The Commission has not made use of its right to initiative with regard to such content of the Prüm Convention. The Prum Decision (2008/615/JHA and its implementing Decision 2008/616/2008) provide for Law Enforcement Cooperation in criminal matters primarily related to exchange of Fingerprint, DNA (both on a hit no-hit basis) and Vehicle registration (direct access via Eucaris system) data. The data exchange provisions are to be implemented until 2012.

Judicial cooperation

Direct Legal Assistance

The Schengen states are obliged to grant each other legal assistance in criminal justice with respect to all types of offences and misdemeanors (Article 49 of the Schengen II Convention), this including tax and other fiscal offences (Article 50 of the Schengen II Convention), except for certain small crimes, as defined in Article 50 of the Schengen II Convention. All Schengen states may serve court documents by mail to another Schengen State, but must attach a translation, if there is reason to believe that the addressee would not understand the original language of the document served (Article 52 of the Schengen II Convention). Requests for legal assistance may be exchanged directly between the judicial authorities of the Schengen states, without having to use diplomatic channels (Article 53 of the Schengen II Convention).

In Articles 54 to 58 of the Schengen II Convention, detailed rules concerning the application of the principle that no person may be sentenced twice for the same criminal offence in the Schengen States are laid down. Articles 59 to 69 of the Schengen II Convention contain rules concerning extradition between Schengen States and the enforcement of prison sentences which were handed down in one state in a different state.

Controlled substances

In Articles 67 to 76 of the Schengen II Convention, rules are laid down with respect to the traffic of controlled substances. The Schengen states are obliged to prosecute illegal trade in narcotics. They have to provide for the forfeiture of profits which derive from illegal trade of controlled substances. The control of cross-border legal trade in such substances has to be exercised in the territory, not at the borders. Persons are permitted to transport controlled substances into the territory of other Schengen states if they carry proper official documentation of an according authorization from a Schengen state, e.g. a medical prescription for narcotics.

Weapons and ammunition

In Articles 77 to 91 of the Schengen II Convention, the control of weapons and ammunition are set out in detail. Regulations regarding which weapons may only be possessed with a valid licence, and which weapons are free, are either contained in the convention itself or may be subject to further legislation at the EU (Schengen) level. Accordingly, the Schengen rules also harmonize the prerequisites for granting permits to produce, purchase, and trade in weapons and ammunition. The according Schengen rules are supplemented by the Council Directive 91/477/EEC of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons,[69] which introduced a European Firearms Pass which entitles the holder to carry a firearm into the territory of other Member States.

Status of membership and implementation

As of 21 December 2007, 24 states and Monaco (treated as part of France) had abolished border controls on persons among themselves, an increase from 15 on 20 December 2007. The nine new countries which entered the Schengen travel area in 2007 were: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.[70] Any non-Schengen traveller having a valid Schengen visa has been allowed to travel throughout these 25 countries from their accession. These states all entered the EU three years previously. They were required to upgrade their border checks with non-Schengen states before border controls would be dropped with them. Cyprus, which entered the EU alongside these other states, did not meet the criteria and thus has requested a delay for a year, while Romania and Bulgaria, who only joined the EU in 2007, are still bringing their border controls up to the required standard.

Prior to the 2007 expansion, the existing fifteen Schengen countries were Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. All but Iceland and Norway are EU members while the United Kingdom and Ireland have opted out from the core Schengen provisions, preferring to keep control over cross-border flows as a matter of joint responsibility. (See the section on the Status of the United Kingdom and Ireland.)

| Flag | State | Area (km²) | Signed or opted in | Date of first implementation | Scope of implementation | Exempted territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 83,871 | 28 April 1995 | 1 December 1997 | full | ||

| Belgium | 30,528 | 14 June 1985 | 26 March 1995 | full | ||

| Bulgaria | 110,912 | 1 January 2007 | not yet implemented | |||

| Cyprus | 9,251 | 1 May 2004 | not yet implemented | |||

| Czech Republic | 78,866 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Denmark | 43,094 | 19 December 1996 | 25 March 2001 | full | ||

| Estonia | 45,226 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Finland | 338,145 | 19 December 1996 | 25 March 2001 | full | ||

| France | 674,843 | 14 June 1985 | 26 March 1995 | full | all overseas departments and territories | |

| Germany | 357,050 | 14 June 1985 | 26 March 1995c | full | ||

| Greece | 131,990 | 6 November 1992 | 26 March 2000 | full | ||

| Hungary | 93,030 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Icelanda | 103,000 | 19 December 1996 | 25 March 2001 | full | ||

| Ireland | 70,273 | 16 June 2000 | 1 April 2002 | Opted out of core Schengen provisions, only police and judicial cooperation rules implemented | ||

| Italy | 301,318 | 27 November 1990 | 26 October 1997 | full | ||

| Latvia | 64,589 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Liechtensteina | 160 | 28 February 2008 | not yet implemented | |||

| Lithuania | 65,303 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Luxembourg | 2,586 | 14 June 1985 | 26 March 1995 | full | ||

| Malta | 316 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Netherlands | 41,526 | 14 June 1985 | 26 March 1995 | full | ||

| Norwaya | 385,155 | 19 December 1996 | 25 March 2001 | full | ||

| Poland | 312,683 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Portugal | 92,391 | 25 June 1992 | 26 March 1995 | full | ||

| Romania | 238,391 | 1 January 2007 | not yet implemented | |||

| Slovakia | 49,037 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Slovenia | 20,273 | 1 May 2004 | 21 December 2007b | full | ||

| Spain | 506,030 | 25 June 1992 | 26 March 1995 | full | ||

| Sweden | 449,964 | 19 December 1996 | 25 March 2001 | full | ||

| Switzerlanda | 41,285 | 26 October 2004 | not yet implemented, as of 27 Nov 2008 full implementation will happen Dec 12th 2008 [1] | |||

| United Kingdom including Gibraltar |

244,820 | 20 May 1999 | 2 June 2000 | Opted out of core Schengen provisions, only police and judicial cooperation rules implemented | and all overseas territories located geographically outside of Europe. |

a States outside the EU that are associated with the Schengen activities of the EU,[71] and where the Schengen rules apply.

b For overland borders and seaports; since 30 March 2008 also for airports.[72]

c East Germany became part of West Germany, joining Schengen, on 3 October 1990. Prior to this it remained outside the agreement.

d Greenland and the Faroe Islands are indirectly included.

e Despite some media reports, Helgoland is not outside Schengen; it is only outside the European Union Value Added Tax Area.

f Mount Athos, an isolated and autonomous monastic community in Greece, has a special exemption from Schengen allowing women to be barred from entry and requiring men to hold a special permit; this is in line with the monks' ancient tradition. See article "The EU respects the 1,000-year old Mount Athos' prohibition of women visitors". greekembassy.org. Hellenic Republic, Embassy of Greece, Washington DC (2001-07-13). Retrieved on 2007-10-22.; see also "Monks see Schengen as Devil's work". BBC News (1997-10-26). Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

g Livigno maintains customs checks and random passport control.

h Campione d'Italia is Italian territory fully surrounded by Switzerland. It does not have VAT on products and will de facto join Schengen once Switzerland joins. There is no border control between Campione d'Italia and Switzerland.

i However, Jan Mayen is in Schengen.

Enlargement

| Prospective members | |

|---|---|

| Prospective implementation date | State |

| 12 December 2008 (land borders[73] and implementation of Schengen visas[74][75]) 29 March 2009 (airports[76]) |

|

| 29 March 2009 (proposed) | |

| 2009 (estimated) | |

| March 2011 (estimated)[78] | |

The Schengen I agreement was originally signed on 14 June 1985, by five European Community states: France, West Germany and the Benelux countries of Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.[81] The Convention Implementing the Schengen Agreement, signed on 19 June 1990, put the agreement into practice.

However, it took until 26 March 1995 for the agreement to be implemented by these countries. By then, Portugal and Spain had also signed. Italy and Greece had also signed, but they did not implement until 1997 and 2000, respectively. All others states also delayed the agreements' implementation. Austria signed in 1995 and implemented two years later. The Nordic states signed in 1996 and implemented in 2001. The Nordic countries had a previous passport free zone separate from the Community, which is why non-EU members Norway and Iceland are party to Schengen — as well as the undesirable cost of heavy policing on the long border which Norway shares with the EU states Sweden and Finland.

Before fully implementing the Schengen laws, each new state will need to have its preparedness assessed in four areas: air borders, visas, police cooperation, and personal data protection. This evaluation process involves a questionnaire and visits of EU experts to selected institutions and workplaces of the country under assessment. The Council of the European Union has reviewed the results between April and September 2007.[82]

Status of the European microstates

Andorra is not integrated into the Schengen area, and border controls remain between it and both France and Spain. Citizens of EU countries require their national identity card to enter Andorra, while anyone else requires a passport or equivalent. Those travellers who need a visa to enter the Schengen area need a multiple-entry visa to visit Andorra, because entering Andorra means leaving the Schengen area.[83]

| Defacto members (open border) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flag | State | Since | Notes | ||

| Monaco | 26 March 1995 | Schengen laws are administered as if Monaco were a part of France, with French authorities carrying out checks at Monaco's sea port. | |||

| San Marino | 26 October 1997 | Although not formally part of the Schengen area, it has an open border with Italy (although some random checks are made by Carabinieri, Polizia di San Marino and Guardia di Finanza). | |||

| Vatican City | 26 October 1997 | It has an open border with Italy and has shown an interest in joining the agreement formally for closer cooperation in information sharing and similar activities covered by the Schengen Information System.[84] | |||

Status of the United Kingdom and Ireland

The United Kingdom and Ireland are the only two EU members prior to the 2004 enlargement that did not sign the 1990 Schengen Convention (Schengen II) and which reserved themselves an opt-out in the Treaty of Amsterdam: Although that treaty transferred the existing Schengen rules into the law of the European Union, which is also applicable in the United Kingdom and in Ireland, not all provisions which were made under the Schengen treaties became applicable in the UK and Ireland. Furthermore, the new EU competence to pass new laws in the areas which were governed by the Schengen rules did not automatically extend to the UK and Ireland. However, the United Kingdom and Ireland may apply for an opt-in to partial or complete application of the Schengen laws.

The UK and Ireland maintain a Common Travel Area with no border controls; thus Ireland is unable to join Schengen without dissolving this agreement with the UK, and incurring controls at its border with Northern Ireland. The UK remains reluctant to surrender its own border control system. In 1999, the UK made use of the possibility to opt in, and asked to participate in a number of provisions of the Schengen acquis, and this was granted by the EU Council on 29 May 2000, having effect on 2 June 2000, also in Gibraltar.[85] Following that, Ireland made a similar request, which was granted by the EU Council on 28 February 2002, effective 1 April 2002.[86] Therefore, the part of the Schengen rules which cover police and judicial co-operation do apply in both the United Kingdom and Ireland, but not the regulations covering visas and border controls.

The reluctance of the UK government to join the agreement has been criticised by the House of Lords[87], which accused the government of hampering the fight against cross-border crime due to the inability of the UK to access the Schengen Information System, which contains data on potentially problematic persons, for immigration control purposes.[88]

In October 2007, the UK Government announced plans to introduce an electronic border control system by 2009 and this led to speculation that the Common Travel Area would end.[89] However, in response to a question on the issue, the Irish Taoiseach Bertie Ahern stated "On the question of whether this is the end of the common travel area and should we join Schengen, the answer is 'No'."[90]

Mutuality of visa requirements

It is a political goal of the European Union to achieve freedom from visa requirements for citizens of the European Union at least in such countries the citizens of which may enter the Schengen area without visa. To this end, the European Commission negotiates with third-countries, the citizens of which do not require visas to enter the Schengen area for short-term stays, about the abolishment of visa requirements which exist for at least some EU member states. The European Commission involves the members state concerned into the negotiations, and has to frequently report on the mutuality situation to the European Parliament and the Council.[91] The Commission may recommend the temporary restoration of the visa requirement for nationals of the third country in question.

The European Commission has dealt with the question of mutuality of the abolishment of visa requirements towards third countries on the highest political level. With regard to Mexico and New Zealand, it already has achieved complete mutuality. With respect to Canada, the Commission has achieved visa-free status for all members but Romania and Bulgaria; with respect to the U.S. it suggests to examine the effects of new legislation enacted there, but reserves itself "the right to propose retaliatory measures."[92]

On the other hand, there are many countries which do not require a visa for citizens of EU countries, but whose citizens need a visa to the Schengen countries. Examples are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Lebanon, the Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Peru, Serbia, Thailand, Turkey and Ukraine.

Statistics

According to information of the European Commission, which is partly based on partly estimated figures received from the Member States, and which was published in connection with the Commission's plans to introduce a biometric entry and exit registration system in the Schengen zone,[93]

- there are 1,792 designated and controlled border crossing points at the external EU border; of them, 665 are located at air borders, 871 at sea borders, and 246 at land borders;

- 880 million persons crossed the external borders of the EU27 in 2005, and 878 million persons did so in 2006; based on the tourism statistics of overnight stays, the statistics lead to a figure of 300 million external border crossings per annum;

- more than 300,000 persons were refused entry at external EU borders in the year 2006, compared to 280,000 in 2005 and 397,000 in 2004; in most cases, refusal was based on insufficient travel documents or the suspicion of intended illegal immigration;

- up to 8 million illegal immigrants stayed within the EU in 2006, an estimated 80% of them within the Schengen area;

- in 2006, 500,000 illegal immigrants were apprehended in the EU, compared to 429,000 in 2005 and 396,000 in 2004, and 75% of the illegal immigrants that were detected on the territory of Member States in the year 2006 were nationals which require a visa to the EU.

According to information of the SaarLorLux Regional Commission, about 167,000 workers commute daily in the Greater Luxembourg Region, crossing an internal Schengen border to get to their workplace.[94] Cross-border commuting in that region makes out 40% of the overall cross-border commuting in the EU15.[95]

As of October 2008, about 733.000 persons were registered in the Schengen Information System for refusal of entry.[96]

History

Pre-Schengen free-travel zones in Europe

Before World War I, one could travel from Paris to Saint Petersburg without a passport.[97] This freedom of movement ended with the war, but several local free-travel zones were later established.

Following Irish independence from the United Kingdom in 1922, no laws were passed requiring a passport for travelling across the newly created international border. The free-travel zone comprising the two countries (the Common Travel Area or CTA) was not codified, or indeed given an official name, until 1997, and then only at the EU level to distinguish it from the Schengen Treaty. See Common Travel Area for further details.

In 1944, the governments-in-exile of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg (Benelux) signed an agreement to eliminate border controls between themselves; this agreement was put into force in 1948.

Similarly, the Nordic Passport Union was created in 1952 to permit free travel amongst the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden and some of their associated territories.

The Schengen Agreement

The Schengen Agreement was originally created independently of the European Union, in part due to the lack of consensus amongst EU members, and in part because those ready to implement the idea did not wish to wait for others to be ready to join. Especially United Kingdom and Denmark could not join the union, but Denmark joined later when Norway and other Nordic countries were allowed.

The Schengen Agreement was signed in Schengen, Luxembourg, on 15 June 1985, by Germany, France, Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg. Since Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg already had passport-free travel, the border tripoint of Luxembourg, Germany and France was considered a suitable place. The exact place of signing was onboard the boat Princesse Marie-Astrid on the Moselle River, near Schengen.

The Convention Implementing the Schengen Agreement, signed on 19 June 1990 by the five countries in Schengen, put the agreement into practice.

Inclusion of the Schengen Laws into the European Union

All states which belong to the Schengen area are European Union members, except Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, which are members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Two EU members (the United Kingdom and Ireland) have opted not to fully participate in the Schengen system (their reasons are outlined above). The main reason that the non-EU states of Iceland and Norway joined was to preserve the Nordic Passport Union (see section Pre-Schengen free-travel zones in Europe).

However, the Treaty of Amsterdam incorporated the legal framework brought about meanwhile, the so-called Schengen-Acquis,[98]by the agreement into the European Union framework, effectively making the agreement part of the EU and its modes of legislature. Amongst other things, at first the Council of the European Union, later the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union in the codecision procedure, took the place of the Executive Committee which had been created under the agreement,[99] leading to the result that legal acts setting out the conditions for entry into the Schengen Area can now be enacted by majority vote in the legislative bodies of the European Union. This also concerns the original Schengen Agreement itself, which may be altered or repealed by means of European Union legislation, without such amendments having to be ratified by the signatory states.[100] Thus, the Schengen States which are not EU members have few options to participate in shaping the evolution of the Schengen rules; their options are effectively reduced to agreeing with whatever is presented before them, or withdrawing from the agreement. Future applicants to the European Union must fulfil the agreement criteria regarding their external border policies in order to be accepted into the EU.

See also

- European Commission

- Maastricht Treaty

- Kaliningrad Oblast an exclave of Russia surrounded by Lithuania and Poland

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Schengen Acquis had been legally defined by the Council Decision of 20 May 1999 concerning the definition of the Schengen acquis for the purpose of determining, in conformity with the relevant provisions of the Treaty establishing the European Community and the Treaty on European Union, the legal basis for each of the provisions or decisions which constitute the acquis (1999/435/EC).

- ↑ At the Schengen I signing ceremony, the "Belgian secretary of state for European affairs said that the agreement’s ultimate goal was "to abolish completely the physical borders between our countries," while Luxembourg’s minister of foreign affairs called it "a major step forward on the road toward European unity," directly benefiting signatory state citizens and "moving them a step closer to what is sometimes referred to as 'European citizenship'." cited on p.48 of Willem Maas, Creating European Citizens, Rowman & Littlefield 2007 ISBN 978-0-7425-5486-3.

- ↑ "Schengen area" is the common name for states that have implemented the agreement.

- ↑ Schengen agreement and the Schengen area

- ↑ The Treaty of Amsterdam

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Consolidated versions of the TEU and the TEC

- ↑ Treaty of Lisbon, article 2, points 63-68

- ↑ Agreement between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders.

- ↑ Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 1985 between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders.

- ↑ Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code).

- ↑ Council Regulation (EC) No 539/2001 of 15 March 2001 listing the third countries whose nationals must be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt from that requirement, original text; this regulation had been amended several times; thus, the lists mentioned in the document linked to is not current.

- ↑ Council Regulation (EC) No 693/2003 of 14 April 2003 establishing a specific Facilitated Transit Document (FTD), a Facilitated Rail Transit Document (FRTD) and amending the Common Consular Instructions and the Common Manual.

- ↑ Common Consular Instructions on Visas for the Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts

- ↑ Council Regulation (EC) No 1683/95 of 29 May 1995 laying down a uniform format for visas.

- ↑ Regulation (EC) No 1987/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on the establishment, operation and use of the second generation Schengen Information System (SIS II).

- ↑ Council Regulation (EC) No 343/2003 of 18 February 2003 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national

- ↑ Commission Regulation (EC) No 1560/2003 of 2 September 2003 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 343/2003 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national.

- ↑ "Council Decision of 22 December 2004 providing for certain areas covered by Title IV of Part Three of the Treaty establishing the European Community to be governed by the procedure laid down in Article 251 of that Treaty" (in English) (2004-12-31). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Article 22 of the Schengen Borders Code.

- ↑ Article 21 (b) of the Schengen Borders Code.

- ↑ "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2008-01-15..

- ↑ Article 7 (b) and (c) of "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2008-01-15..

- ↑ Article 7 subsec. 2 of the "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2007-11-25.; with respect to identification by identity cards cf. Article 5 subsec. 1 of the "Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States" (PDF) (in English) (2004-04-40). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Article 7 subsection 3 vi of the "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Article 7 subsection 2 subparagraph 3 of the "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Details are set out in Annex VI to the "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ One camera at every 186 metres of the border: "Stories from Schengen: Smuggling cigarettes in Schengen Slovakia" (in English) (2008-01-09). Retrieved on 2008-03-09..

- ↑ Article 26 sec. 1 lit. b of the Schengen II Agreement.

- ↑ Article 5 of the Schengen Borders Code - "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Cf. Article 6 of "Consolidated verion of the Council Regulation (EC) No 539/2001 of 15 March 2001 listing the third countries whose nationals must be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt from that requirement" (PDF) (in English) (2007-01-19). Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- ↑ Article 19 of the Schengen II Agreement for third-country nationals requiring a visa; Article 20 of the Schengen II Agreement for third-country nationals who do not require such visa.

- ↑ Article 21 of the Schengen II Agreement.

- ↑ "Consolidated verion of the Council Regulation (EC) No 539/2001 of 15 March 2001 listing the third countries whose nationals must be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt from that requirement" (PDF) (in English) (2007-01-19). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Cf. "17.html Section 17 of the German Aufenthaltsverordnung" (in German) (2004-11-25). Retrieved on 2007-11-28. in conjunction with "16.html Section 16 of the German Beschäftigungsverordnung" (in German) (2004-11-22). Retrieved on 2007-11-28..

- ↑ This is set out in detail in the Common Consular Instructions:"Consolidated verion of the Common Consular Instructions on Visas for the Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts" (PDF) (in English) (2003-05-01). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ "Consolidated verion of the Council Regulation (EC) No 415/2003 of 27 February 2003 on the issue of visas at the border, including the issue of such visas to seamen in transit" (PDF) (in English) (2003-03-07). Retrieved on 2007-11-25..

- ↑ Article 12 sec. 2 sentence 1 of the Schengen II Agreement.

- ↑ Article 12 sec. 2 sentence 2 of the Schengen II Agreement.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Embassy of Denmark, New Delhi. "Visa requirements for Indians travelling to Denmark". Retrieved on 2007-12-25.

- ↑ Article 21 of the Schengen Agreement.

- ↑ "Council Directive 2003/109/EC concerning the status of third-country nationals who are long-term residents" (PDF) (in English) (2004-01-23). Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- ↑ "Entry procedures for their family members who are not Union citizens themselves (European Union)" (in English). Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ↑ "Right of Union citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the Union, Guide on how to get the best out of Directive 2004/38/EC" (PDF) (in English). Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ↑ "Decision of the EEA Joint Committee No 158/2007 of 7 December 2007 amending Annex V (Free movement of workers) and Annex VIII (Right of establishment) to the EEA Agreement" (in English). Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ↑ The "Statutory Instrument 2006 No. 1003 - The Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2006" (in English). refers only to residence permits issued by the UK themselves (see definition of "residence card" in this section).

- ↑ Article 4(2) of the "Real Decreto 240/2007, de 16 de febrero" (in Spanish). refers to Schengen residence permits only.

- ↑ "Regulation (EC) No 1931/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 laying down rules on local border traffic at the external land borders of the Member States and amending the provisions of the Schengen Convention" (in English) (2006-12-30). Retrieved on 2008-03-02.

- ↑ See Schengen and Slovenia / Third-country nationals at "Republic of Slovenia: Ministry of the Interior: FAQ about Schengen" (in English). Retrieved on 2008-03-02..

- ↑ "Commission launches dialogue with Albania on visa free travel" (in English) (2008-04-05). Retrieved on 2008-03-06.

- ↑ "Commission launches dialogue with Montenegro on visa free travel" (in English) (2008-04-05). Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Commission launches dialogue with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia on visa free travel" (in English) (2008-02-20). Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "EC: Visa abolition possible by 2009" (in English) (2008-04-05). Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ Article 45 of the Schengen II Convention.

- ↑ Article 120 of the Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 1985 between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders.

- ↑ Cf. the excemption of the application of Articles 2 (4) and 120 to 125 according to Annex A of the Agreement concluded by the Council of the European Union and the Republic of Iceland and the Kingdom of Norway concerning the latters' association with the implementation, application and development of the Schengen acquis - Final Act.

- ↑ Article 21 of the "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2008-01-24..

- ↑ Article 2 No. 10 of the "Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code)" (PDF) (in English) (2006-04-13). Retrieved on 2008-01-15..

- ↑ Information of the airport company of Reykjavik/Iceland: Passport Control & Schengen, section Schengen does not change customs control procedures in the Schengen territory: “Travellers to this country from a European country within the Schengen territory are […] subject to the same regulations as before concerning routine customs inspection in Leifur Eiriksson Terminal or at a harbour in this country.”

- ↑ Cf. Article 21 of the Schengen Borders Code, which allows for such checks “insofar as the exercise of those powers does not have an effect equivalent to border checks”, as further defined in that Article.

- ↑ "Switzerland links up to European police files" (2008-08-11). Retrieved on 2008-09-07..

- ↑ In particular, the application of Articles 2 (4) and 120 to 125 of the Schengen II Convention is exempted from application in Switzerland according to Annex A Part 1 of the "Agreement between the European Union, the European Community and the Swiss Confederation on the Swiss Confederation's association with the implementation, application and development of the Schengen acquis" (PDF) (in English). consilium.europa.eu (2004-10-25). Retrieved on 2008-01-23..

- ↑ "Schengen-Abkommen: Auswirkungen auf die Kontrollen an der Schweizer Grenze" (in German). admin.ch. Swiss Federal Department of Finance (2004-06-21). Retrieved on 2008-01-23..

- ↑ Portal des Fürstentums Liechtenstein - - Medien / Presse - Pressemeldungen

- ↑ Portal des Fürstentums Liechtenstein - - Medien / Presse - Pressemeldungen

- ↑ "Schweiz soll ab 1. November 2008 bei Schengen dabei sein" (in German). NZZ.ch (2007-09-19). Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Example: Press releases concerning police coopration in the German-Polish border region - "Innenminister Schönbohm: Schengen-Erweiterung ein „historisches Glück“" (in German) (2007-11-22). Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- ↑ Cf. Article 24 of the "Prüm Agreement (Schengen III Agreement)" (PDF) (in German). Retrieved on 2008-01-22., and sec. 64 (4) of the German Federal Police Act.

- ↑ "Council Decision 2008/615/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime".