Saul

Saul (שאול המלך) (or Sha'ul) (Arabic: طالوت ,Tālūt) (Hebrew: שָׁאוּל, Standard Šaʾul Tiberian Šāʾûl ; "asked for") (reigned 1047 - 1007 BCE) is identified in the Books of Samuel, 1 Chronicles and the Qur'an as the first king of the ancient United Kingdom of Israel and Judah.[1] Saul reigned from Gibeah during the closing decades of the 2nd millennium BC. He died during a battle with the Philistines, when a part of his kingdom succumbed to Philistine control and occupation. The succession was contested by his surviving son Ish-bosheth and their common rival David. Saul's traditional biography in the Books of Samuel has been said by Biblical critics (see section below) to reveal two main sources, independent of each other.

Contents |

Nativity

According to the Tanakh, Saul was the son of Kish, of the family of the Matrites, and a member of the tribe of Benjamin, one of the twelve Tribes of Israel. (1 Samuel 9:1-2; 10:21; 14:51; Acts 13:21) It appears that he came from Gibeah. Saul was married to Ahinoam, daughter of Ahimaaz, and they had four sons: Jonathan, Abinadab, Malchishua and Ish-bosheth, and two daughters, Merab and Michal, whom Saul had given in marriage to David, who became Saul's rival to the kingship of Israel. When Saul fell out with David, he gave Michal in marriage to Palti son of Laish. Saul also had a concubine named Rizpah, daughter of Aiah, and they had two sons, Armoni and Mephibosheth.

Three of his sons died with him at the Battle of Mount Gilboa (1 Samuel 31:2), leaving only Ish-bosheth surviving to follow him as king. Ish-bosheth became king at the age of forty (2 Samuel 2:10) and Michal was returned as wife to David. Ish-bosheth reigned for two years and was killed by two of his own captains (2 Samuel 4:5). Michal was childless.

Saul was buried in Zela, in the region of Benjamin in modern-day Israel. (2 Samuel 21:14)

Anointed as king

In the source telling of his anointing (1 Samuel 9:1-16), Saul is not referred to as a king (melech), but rather as a “leader” or “commander” (nagid) (1 Samuel 9:16; 1 Samuel 10:1). [2] However (possibly representing an opposing literary strain), Saul is said to be made a "king" (melech) at Gilgal (1 Samuel 11:15). Even David, before he was anointed king, was referred to only as a future nagid, or military commander (1 Samuel 13:14).

The people generally used the term “king,” because their desire was to be like the other nations (1 Samuel 8:5; 10:19). This may be indicative of the difference between what a certain faction of the people wanted, and a definite reluctance of certain leaders (e.g., the prophet Samuel) to break from the old tribal order: viz., an attempt to satisfy everyone without creating a riot. But Saul was finally crowned as "king" (melech) in Gilgal. (1 Samuel 11:14-12:2)

Saul's reign is said to be only two years in length - [1 Samuel 13:1], although Acts 13:21 renders this as 40 years. Two years would be impossible since it is written that he became king at 30 and Ish-bosheth, his son, was 40 when Saul died.

The Books of Samuel give three distinct accounts of how Saul came to be anointed as king:

- (1 Samuel 9:1-10:16) Saul was sent with a servant to look for his father's donkeys, who had strayed; leaving his home at Gibeah, they eventually wander to the district of Zuph, at which point Saul suggests abandoning their search. Saul's servant however, remarks that they happened to be near the town of Ramah, where a famous seer was located, and suggested that they should consult him first. The seer (later identified by the text as Samuel), having previously had a vision instructing him to do so, offers hospitality to Saul when he enters Ramah, and later anoints him in private.

- (1 Samuel 10:17-24 and 12:1-5) Desiring to be like other nations, there was a popular movement to establish a centralised monarchy. Samuel therefore assembled the people at Mizpah in Benjamin, and despite having strong reservations, which he made no attempt to hide, allows the appointment of a king. Samuel uses cleromancy to determine who it was that God desired to be the king, whittling the assembly down into ever smaller groups until Saul is finally identified. Saul, hiding in baggage, is then publicly anointed.

- (1 Samuel 11:1-11 and 11:15) The Ammonites, led by Nahash, lay siege to Jabesh-Gilead, who are forced to surrender. Under the terms of surrender, the occupants of the city would be forced into slavery, and have their right eyes removed as a sign of this. The city's occupants send out word of this to the other tribes of Israel, and the tribes west of the Jordan assemble an army under the leadership of Saul. Saul leads the army to victory against the Ammonites, and, in both gratitude and appreciation of military skill, the people congregate at Gilgal, and acclaim Saul as king.

Rejection

According to 1 Samuel 10:8, Samuel had told Saul to wait for him for seven days before Samuel meets him and gives him further instructions. But as Samuel did not arrive early after 7 days (1 Samuel 13:8) and the Israelites became restless, Saul started preparing for battle by offering sacrifices; Samuel arrived just as Saul finished offering his sacrifices and reprimanded Saul for not obeying Samuel's instructions and said that as a result of not keeping God's instructions, God will take away his kingship (1 Samuel 13:14).

After the battle with the Philistines was over, the text describes Samuel as having instructed Saul to kill all the Amalekites, in accordance with the mitzvah to do so. Having forewarned the Kenites living among the Amalekites to leave, Saul went to war and defeated the Amalekites, but only killed all the babies, women, children, poor quality livestock and men, leaving alive the king and best livestock.

When Samuel found out that Saul has not killed them all, he becomes angry and launches into a long and bitter diatribe about how God regretted making Saul king, since Saul is disobedient. When Samuel turns away, Saul grabs Samuel by his clothes tearing a small part of them off, which Samuel states is a prophecy about what would happen to Saul's kingdom. Samuel then commands that the Amalekite king (who, like all other Amalekite kings in the Hebrew Bible, is named Agag) should be brought forth. Samuel proceeds to kill the Amalekite himself and makes a final departure.

David's introduction

It is at this point that David, a son of Jesse, from the tribe of Judah, enters the story. According to the narrative, David comes to prominence on three occasions:

- (1 Samuel 16:1-13) Samuel is surreptitiously sent by God to Jesse. While offering a sacrifice in the vicinity, Samuel includes Jesse among the invited guests. Dining together, Jesse's sons are brought one by one to Samuel, each time being rejected by him; running out of sons, Jesse sends for David, the youngest, who was tending sheep. When brought to Samuel, David is anointed by him in front of his other brothers.

- (1 Samuel 16:14-23) Saul is troubled by an evil spirit sent by God (some translations euphemistically just describe God not preventing an evil spirit from troubling Saul). Saul requests soothing music, and a servant recommends David the son of Jesse, who is renowned as a skillful harpist and soldier. When word of Saul's needs reach Jesse, he sends David, who had been looking after a flock, and David is appointed as Saul's armor bearer. David remains at court playing the harp as needed by Saul to calm his moods.

- (1 Samuel 17:1-18:5) The Philistines return with an army to attack Israel, but, having amassed on a hillside opposite to the Israelite forces, suggest that to save effort and lives on both sides, it would be better to have a proxy combat between their champion, a Rephaim from Gath named Goliath, and someone of Saul's choosing. David, a young shepherd boy, happens to be delivering food to his three eldest brothers, who are in the Israelite army, at the time that the challenge is made. David, who is somewhat cocksure, talks to the nearby soldiers mocking the Philistines, but is told off by his brothers for doing so. David's speech is overheard and reported to Saul, who does not know David, but summons David, and on hearing David's views decides to kit him out with his (Saul's) own armour. Saul then appoints David as his champion, and David slays Goliath with a mere shot from a sling, which hits him in the eyes. Goliath falls forward, defeated,

The use of a sling to cause Goliath's death is not as remarkable as it at first seems; many soldiers in the ancient near east were equipped with slings as their main weapon. For example, there are several Assyrian carvings of their use as of the 7th century BC.

Saul's love of glory

In the text, after David is introduced at court, Jonathan becomes extremely fond of him, to the extent of loving him as himself, and giving his military clothes to David to symbolize David's position as successor to Saul. After David returns from killing Goliath, the women heap praise upon him, and refer to him as a greater military hero than Saul, driving Saul to jealousy, fearing that David constituted a rival to the throne.

Another day, while David is playing the harp, Saul, possessed by an evil spirit, throws a spear at him but misses on two occasions. Saul resolves to remove David from the court and appoints him an officer, but David becomes increasingly successful, making Saul more resentful of him. In return for being his champion, Saul offers to marry his daughter, Merob, to David, but David turns the offer down claiming to be too humble and Merob is married to another man instead. Another daughter, Michal, falls in love with David, so Saul repeats the offer to David with Michal, but again David turns it down claiming to be too poor; Saul persuades David that the bride price would only be 100 foreskins from the Philistines, hoping that David would be killed trying to achieve this. David obtains 200 foreskins and is consequently married to Michal.

The narrative continues as Saul plots against David, but Jonathan dissuades Saul from this course of action, and tells David of it. Saul then tries to have David killed during the night, but Michal helps him escape and tricks his pursuers by using a household idol to make it seem that David is still in bed. David flees to Jonathan, who wasn't living near Saul. Jonathan agrees to return to Saul and discover his ultimate intent. While dining with Saul, Jonathan pretends that David has been called away to his brothers, but Saul sees through this and castigates Jonathan for being the companion of David, and it becomes clear that Saul wants David dead. The next day, Jonathan meets with David and tells him Saul's intent, and the two friends say their goodbyes, as David flees into the country. Saul later marries Michal to another man instead of David.

Saul is later informed by his head shepherd,an Edomite named Doeg, that Ahimelech assisted David. A henchman is sought to kill Ahimelech and the other priests of Nob. None of Saul's henchmen is willing to do this, so Doeg offers to do it instead, killing 85 priests. Saul also kills every man, woman and child living in Nob.

David had already left Nob by this point and had amassed about 400 disaffected men including a group of outlaws. With these men David launched an attack on the Philistines at Keilahhe. Saul realised he could trap David and his men inside the city and besiege it. However, David hears about this, and having received divine council (via the Ephod), finds that the citizens of Keilah would betray him to Saul, decides to leave and flees to Ziph. Saul discovers this and pursues David on two occasions:

- Some of the inhabitants of Ziph betray David's location to Saul, but David hears about it and flees with his men to Maon. Saul follows David, but while Saul travels along one side of the gorge, David travels along the other, and Saul is forced to break off pursuit when the Philistines invade. This is supposedly how the place became known as the gorge of divisions. David hides in the caves at Engedi and after fighting the Philistines, Saul returns to Engedi to attack him. Saul eventually enters the cave in which David had been hiding, but as David was in the darkest recesses Saul doesn't spot him. David swipes at Saul and cuts off part of his garment, but restrains himself and his associates from going further due to a taboo against killing an anointed king. David then leaves the cave, revealing himself to Saul, and gives a speech that persuades Saul to reconcile.

- On the second occasion Saul returns to Ziph with his men. When David hears of this he sneaks into Saul's camp by night, and thrusts his spear into the ground near where Saul was sleeping. David prevents his associates from killing Saul due to a taboo against killing an anointed king, and merely steals Saul's spear and water jug. The next day, David stands at the top of a slope opposite to Saul's camp, and shouts that he had been in Saul's camp the previous night (using the spear and jug as proof). David then gives a speech that persuades Saul to reconcile with David, and the two make an oath not to harm one another.

Is Saul among the prophets?

The phrase is Saul among the prophets, is mentioned by the text in a way that suggests it was a popular phrase or proverb in later Israelite culture, perhaps in a similar way to is the Pope a Catholic. It is given an etymology on two separate occasions:

- (1 Samuel 10:11 etc.) Having been anointed by Samuel, Saul is told of signs he will receive to know that he has been divinely appointed. The last of these signs is that Saul will be met by an ecstatic group of prophets leaving a high place and playing music on lyre, tambourine, and flutes. The signs come true (though the text skips the first two, suggesting that a portion of the text has been lost, or edited out for some reason), and Saul joins the ecstatic prophets, hence the phrase.

- (1 Samuel 19:24 etc.) Saul sends men to pursue David, but when the men meet a group of ecstatic prophets playing music on lyre, tambourine, and flute, they become overcome with a prophetic state and join in. Saul sends more men, but they too join the prophets. Eventually Saul himself goes, and also joins the prophets, hence the phrase.

According to textual criticism, the reason for these two quite different explanations is that they come from two different sources - the first from the monarchical source, which portrays the phrase as casting Saul in a positive light, while the second is considered to come from the republican source, and suggests the phrase was a mockery of Saul. Which of these is the true origin of the phrase, or whether another explanation is the genuine one, is unknown.

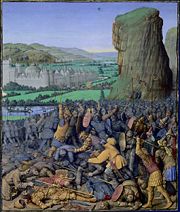

Battle of Gilboa

Despite the oath(s) of reconciliation, the biblical text states that David felt insecure, and so made an alliance with the Philistines, becoming their vassal. Emboldened by this, the Philistines prepared to attack Israel, and Saul led out his army to face them at Gilboa, but before the battle decided to secretly consult the witch of Endor for advice. The witch, unaware of who he is, reminds Saul that the king (i.e. Saul himself) had made witchery a capital offence, but after being assured that Saul wouldn't harm her, the witch conjures up the ghost of Samuel. Samuel's ghost tells Saul that he would lose the battle and his life.

Broken in spirit, Saul returns to face the enemy, and the Israelites are duly defeated. To escape the ignominy of capture, Saul asks his armour bearer to kill him, but is forced to commit suicide by falling on his sword when the armour bearer refuses. An Amalekite then claims to have killed Saul, and when the Amalekite tells David, David orders the Amalekite to be put to death. The body of Saul, with those of his sons, were fastened to the wall of Beth-shan, and his armor was hung up in the house of Ashtaroth. The inhabitants of Jabesh-gilead (the scene of Saul's first victory) rescue the bodies and take them to Jabesh-gilead, where they burn their flesh, and bury the bones (Sam.I 31,13).

Textual criticism

The biography of Saul in the books of Samuel has been subjected to much criticism and analysis by Biblical scholars in attempts to uncover the original sources of the books and the motives of the writers. Their arguments include the following;

A few scholars propose that the Biblical story of Samuel's birth may originally have referred to Saul. Hannah, who had been childless, had begged God for a son, and when she later became pregnant named the son Shmuel to reflect this; meaning this passage now refers to a different person, the last of the Hebrew Judges, rather than the person who would become king.[3] These scholars, however, find Shmuel (literally name of God) an odd name to be explained by this etymology; the traditional translation heard of God (i.e. God heard) requires a linguistically awkward rendering, as heard of God is actually Shamael; Saul, on the other hand, would have fit the explanation near-perfectly, since the Hebrew term used for asked is sha'ul.[4] However, these difficulties seem to be due to an error in interpreting the name, as it is more logical to understand Shmu'el as "Shamu 'El", God is Elevated, (like in "shumu shamaim")

According to others, the existence of three different explanations for Saul's rise to kingship is the result of the biblical narrative being spliced together from a number of originally distinct source texts. This may be supported by text-critical evidence: in the Septuagint version of 1 Samuel 11:15, Saul is being publicly anointed as king by Samuel at Gilgal, rather than the crowd simply acclaiming him as such; i.e. Saul gets anointed three times, and twice publicly.

Biblical scholars[5] argue that the three accounts are a reasonable process of gradual acceptance for the political climate of the time. Given that Israel was a loose confederation of tribes united by their faith, and without a strong political or theological leader, Sanford argues that a series of displays of ability (or, from a theological point of view, gifts from God as evidence that he was divinely chosen for rulership) were needed to bring all the tribes on board for the inevitable loss of individual freedom resulting from the institution of a monarchy.

Claims have also been made that the numbers in the account of the battle with the Philistines are grossly unrealistic, claiming they had 30,000 chariots for example (although it should be noted that the later Septuagint and Syriac versions, used by more modern translations such as the NIV, reduce the number to 3,000). Also considered unrealistic by historians is the suggestion by the text that Saul and his son Jonathan were the only men apart from the Philistines that had weapons; textual critics also believe that this suggestion (1 Samuel 13:19-22) is a later addition to the text, particularly as the narrative flows more naturally from the end of verse 18 onto the start of verse 23.

Scholars of biblical criticism, propose that the fact that the Israelites were led by a man named Jonathan is simply an ethnology - indicating that the Hebrews were a branch of Israelites (and distinct from the others), rather than that they were led by a son of the Israelite King.

According to textual critics, both the earlier passage about Saul's impatience (1 Samuel 13:7b-15a) and the later narrative of the Amalekite war (1 Samuel 15) are later redactions of the text that belong together. These are both designed to justify the later fate of Saul and division in his kingdom, when Saul had seemingly been divinely chosen to be king, and simultaneously portray ancient Israel as more of a theocracy than it would otherwise have appeared to be, making a king appear to take orders from a prophet.

Textual scholars see the three narratives of David's rise to kingship as coming from three distinct sources; the first, in which David is anointed, being a late redaction into the text so as to portray David as having been divinely appointed, and to insert a prophet into the role of kingmaker, to be more suggestive of theocracy. The second narrative, which mocks Saul as being afflicted by an evil spirit, is thought to come from the republican source.

The third narrative, which is the most famous, is thought by some to come from a monarchical source. It sits uneasily with the second; David, a renowned warrior who has just been appointed in court as Saul's armour bearer (narrative 2), is very shortly afterward an unknown unarmored young shepherd boy delivering food to his brothers (narrative 3). An attempt to smooth over elements of these difficulties of the masoretic text appears to have been made by the Septuagint, which excludes the passages referring to David delivering food to his brothers, and Saul not having known him (specifically 17:12-31, 17:41, 17:50, 17:55-18:5) - these passages are marked with brackets in some translations.

The third narrative also appears to contradict 2 Samuel 21:19, which says that Elchanon, a soldier working for David, slew Goliath (a few translations smooth over this by claiming that Elchanon slew a brother of Goliath). Scholars of biblical criticism generally consider the older tradition to be the one in which Elhanen slew Goliath, the tradition in which it was David, and in which it was the reason for defeat of the entire Philistine army, coming into existence to make David appear even more skilled/historically important than he actually was in reality.

According to textual scholars, the fact that David spares Saul's life on two occasions is the result of the splicing together of two earlier narratives - the republican source and the monarchical source; the republican source being responsible for the passages involving Jonathan, the first pursuit to Ziph and the first reconciliation; the monarchical source being responsible for the passages involving Michal, Nob, the second pursuit to Ziph and the second reconciliation. Michal essentially plays the same role in the monarchical source as Jonathan does in the republican source - as David's protector in Saul's court.

Both narratives are interesting to scholars of biblical criticism, who, for example, view the republican source as having incorporated a folk etymology for the gorge of divisions into the narrative. The monarchical source mentioning a household idol is of interest as it indicates that such things existed and were not regarded as inappropriate in early Yahweh-religion; archeology confirms a large number of household idols existed in early Israel, particularly statues of Asherah, a Canaanite god considered by some of the Baal-worshippers to be his's wife (according to inscriptions on a number of surviving Asherah statues).

David's relationship with Jonathan, and David's subsequent flight, is seen by some as being an eponym-type narrative, in which nations are treated as people - David representing the Kingdom of Judah and Jonathan representing the Hebrews (who the text of the books of Samuel appears to treat as distinct from Israel or Judah). David's 400 strong army thus would constitute the army of Judah (compare Saul's 600 strong army of Israel), while Jonathan's visits and association with David reflects an alliance between the Hebrews and Judah which became more important than the alliance between the Hebrews and Israel. In essence the narrative of David's flight and reconciliation with Saul becomes one of a rebellion by Judah, assisted by the Hebrews, that eventually became an uneasy truce.

Classical Rabbinical views

Two opposing views of Saul are found in classical rabbinical literature. One is based on the reverse logic that punishment is a proof of guilt, and therefore seeks to rob Saul of any halo which might surround him; typically this view is similar to the republican source. The passage referring to Saul as a choice young man, and goodly (1 Samuel 9:2) is in this view interpreted as meaning that Saul was not good in every respect, but goodly only with respect to his personal appearance (Num. Rashi 9:28). According to this view, Saul is only a weak branch (Gen. Rashi 25:3), owing his kingship not to his own merits, but rather to his grandfather, who had been accustomed to light the streets for those who went to the bet ha-midrash, and had received as his reward the promise that one of his grandsons should sit upon the throne (Lev. Rashi 9:2).

The second view of Saul makes him appear in the most favourable light as man, as hero, and as king. This view is similar to that of the monarchical source. In this view it was on account of his modesty that he did not reveal the fact that he had been anointed king (1 Samuel 10:16; Meg. 13b); and he was extraordinarily upright as well as perfectly just. Nor was there any one more pious than he (M. Ḳ. 16b; Ex. Rashi 30:12); for when he ascended the throne he was as pure as a child, and had never committed sin (Yoma 22b). He was marvelously handsome; and the maidens who told him concerning Samuel (cf 1 Samuel 9:11-13) talked so long with him that they might observe his beauty the more (Ber. 48b). In war he was able to march 120 miles without rest. When he received the command to smite Amalek (1 Samuel 15:3), Saul said: For one found slain the Torah requires a sin offering [Deuteronomy 21:1-9]; and here so many shall be slain. If the old have sinned, why should the young suffer; and if men have been guilty, why should the cattle be destroyed? It was this mildness that cost him his crown (Yoma 22b; Num. Rashi 1:10) —the fact that he was merciful even to his enemies, being indulgent to rebels themselves, and frequently waiving the homage due to him. But if his mercy toward a foe was a sin, it was his only one; and it was his misfortune that it was reckoned against him, while David, although he had committed much iniquity, was so favored that it was not remembered to his injury (Yoma 22b; M. Ḳ 16b, and Rashi ad loc.). In many other respects Saul was far superior to David, e.g., in having only one concubine, while David had many. Saul expended his own substance for the war, and although he knew that he and his sons would fall in battle, he nevertheless went boldly forward, while David heeded the wish of his soldiers not to go to war in person (2 Samuel 21:17; Lev. Rashi 26:7; Yalḳ., Sam. 138).

According to the Rabbis, Saul ate his food with due regard for the rules of ceremonial purity prescribed for the sacrifice (Yalḳ., l.c.), and taught the people how they should slay cattle (cf 1 Samuel 14:34). As a reward for this, God himself gave Saul a sword on the day of battle, since no other sword suitable for him was found (ibid 13:22). Saul's attitude toward David finds its excuse in the fact that his courtiers were all tale-bearers, and slandered David to him (Deut. Rashi 5:10); and in like manner he was incited by Doeg against the priests of Nob (1 Samuel 22:16-19; Yalḳ., Sam. 131) - this act was forgiven him, however, and a heavenly voice (bat ḳol) was heard, proclaiming: Saul is the chosen one of God (Ber. 12b). His anger at the Gibeonites (2 Samuel 21:2) was not personal hatred, but was induced by zeal for the welfare of Israel (Num. Rashi 8:4). The fact that he made his daughter remarry (1 Samuel 25:44), finds its explanation in his (Saul's) view that her betrothal to David had been gained by false pretenses, and was therefore invalid (Sanhedrin 19b). During the lifetime of Saul there was no idolatry in Israel. The famine in the reign of David (cf 2 Samuel 21:1) was to punish the people, because they had not accorded Saul the proper honours at his burial (Num. Rashi 8:4). In Sheol, Saul dwells with Samuel, which is a proof that all has been forgiven him ('Er. 53b).

Old Testament scholars view

Two opposing viewpoints exist regarding Saul's visit with the witch of Endor. Some scholars believe that God miraculously intervened and Saul spoke to Samuel himself. Other scholars believe that the encounter with the witch was a demonic manifestation of transforming itself to appear to be Samuel (Isaiah 5:11). Regarding Saul's salvation, many believe that God's mercy was taken away from him because of his disobedience and refusal to repent (1 Samuel 13:13-14).

References

- Wellhausen, Der Text der Bücher Samuelis

- K. Budde, Die Bücher Richter und Samuel, 1890, pp. 167-276;

- S. R. Driver, Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Samuel, 1890;

- T. K. Cheyne, Aids to the Devout Study of Criticism, 1892, pp. 1-126;

- H. P. Smith, Old Testament History, 1903, ch. vii.;

- Cheyne and Black, Encyclopedia Biblica

Notes

- ↑ "Saul (King) - Biblical people". AboutBibleProphecy.com. Retrieved on 2008-05-10.

- ↑ Bright, John, "A History of Israel," The Westminster Press, Philadelphia, 1972, p. 185.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Carl S. (editor), “Saul in Story and Tradition” Mohr Siebeck, (2006), p. 126.

- ↑ Ronald A. Simkins. "Samuel and Saul: The Rise of Kingship". Creighton University. Retrieved on 2008-04-18.

- ↑ Lasor, William Sanford, et al. (1996), “Old Testament Survey,” Eerdmans Pub Co., ISBN 0802837883.

See also

- Islamic view of Saul

External links

|

Saul of the United Kingdom of Israel & Judah

House of Saul

Cadet branch of the Tribe of Benjamin

|

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title Anointed king to

replace Judge Samuel |

King of the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah 1047 BC – 1007 BC |

Succeeded by Ish-bosheth |

| Prophets of Judaism & Christianity in the Hebrew Bible | ||

|---|---|---|

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob · Moses (rl) · Aaron · Miriam · Eldad & Medad · The seventy elders of Israel · Joshua · Phinehas | ||

|

|

||

| Deborah · Samuel · Saul · Saul's men · David · Jeduthun · Solomon | Gad · Nathan · Ahiyah · Elijah · Elisha | Isaiah (rl) · Jeremiah · Ezekiel | ||

|

|

||

| Hosea · Joel · Amos · Obadiah · Jonah (rl) · Micah · Nahum · Habakkuk · Zephaniah · Haggai · Zechariah · Malachi | ||

|

|

||

| Shemaiah · Iddo · Azariah · Hanani · Jehu · Micaiah · Jahaziel · Eliezer · Zechariah ben Jehoiada · Oded · Huldah · Uriah | ||

|

|

||

| Judaism: Sarah (rl) · Rachel· Rebecca · Joseph · Eli · Elkanah · Hannah (mother of Samuel) · Abigail · Amoz (father of Isaiah) · Beeri (father of Hosea) · Hilkiah (father of Jeremiah) · Shallum (uncle of Jeremiah) · Hanamel (cousin of Jeremiah) · Buzi · Mordecai · Esther · (Baruch) |

Christianity: Abel · Enoch (ancestor of Noah) · Daniel |

|

| Non-Jewish: Kenan · Noah (rl) · Eber · Bithiah · Beor · Balaam · Balak · Job · Eliphaz · Bildad · Zophar · Elihu | ||

This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia article "Saul" by Joseph Jacobs, Ira Maurice Price, Isidore Singer, and Jacob Zallel Lauterbach, a publication now in the public domain.