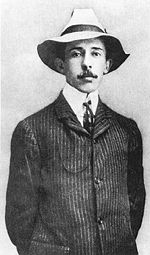

Alberto Santos-Dumont

| Alberto Santos-Dumont | |

|

|

| Born | July 20, 1873 Palmira, Minas Gerais |

|---|---|

| Died | July 23, 1932 Guarujá, São Paulo |

Alberto Santos-Dumont (July 20 1873 – July 23 1932) was an early pioneer of aviation. He was born and died in Brazil. He spent most of his adult life in France. His contributions to aviation took place while he was living in Paris, France.

Santos-Dumont designed, built, and flew the first practical dirigible balloons. In doing so he became the first person to demonstrate that routine, controlled flight was possible. This "conquest of the air", in particular winning the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize on October 19 1901 on a flight that rounded the Eiffel Tower, made him one of the most famous people in the world during the early 20th century. In addition to his pioneering work in airships, Santos-Dumont made the first public European flight of an airplane in Paris on October 23 1906. Designated 14-bis or Oiseau de proie (French for "bird of prey"), the flying machine was the first fixed-wing aircraft officially witnessed to take off, fly, and land. Considerable controversy still exists about similar claims of first flight. For his achievements, Santos-Dumont is known in Brazil as "The Father of Aviation".

Contents |

Childhood

Santos-Dumont was born in Cabangu Farm, a farm in the Brazilian town of Palmira, today named Santos Dumont in the state of Minas Gerais. He grew up as the sixth of eight children on a coffee plantation owned by his family in the state of São Paulo. His French-born father was an engineer, and made extensive use of the latest labor-saving inventions on his vast property. So successful were these innovations that Santos-Dumont's father gathered a large fortune and became known as the "Coffee King of Brazil."

He was fascinated by machinery, and while still a young child he learned to drive the steam tractors and locomotive used on his family's plantation. He was also a fan of Jules Verne and had read all his books before his tenth birthday. He wrote in his autobiography that the dream of flying came to him while contemplating the magnificent skies of Brazil in the long, sunny afternoons at the plantation.

According to the custom of wealthy families of the time, after receiving basic instruction at home with private instructors including his parents, young Alberto was sent out alone to larger cities to do his secondary studies. He studied for a while in "Colégio Culto à Ciência", in Campinas.

Move to France

In 1891, Alberto's father had an accident while inspecting some machinery. He fell from his horse and became a paraplegic. He decided to sell the plantation and move to Europe with his wife and younger children. At seventeen, Santos-Dumont left the prestigious Escola de Minas in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, for Paris in France. The first thing he did there was to buy an automobile. Later, he pursued studies in physics, chemistry, mechanics, and electricity with the help of a private tutor.

Balloons and dirigibles

Santos-Dumont described himself as the first "sportsman of the air." He started flying by hiring an experienced balloon pilot and took his first balloon rides as a passenger. He quickly moved on to piloting balloons himself, and shortly thereafter to designing his own balloons. In 1898, Santos-Dumont flew his first balloon design, the Brésil.

After numerous balloon flights, he turned to the design of steerable balloons or dirigible type balloons that could be propelled through the air rather than drifting along with the breeze (See Airship).

Between 1898 and 1905, he built and flew 11 dirigibles. Some were engine and some pedal powered. With air traffic control restrictions still decades in the future, he would glide along Paris boulevards at rooftop level in one of his airships, commonly landing in front of a fashionable outdoor cafe for lunch. On one occasion he even flew an airship early one morning to his own apartment at No. 9, Rue Washington, just off Avenue des Champs-Élysées, not far from the Arc de Triomphe.

To win the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize Santos-Dumont decided to build a bigger balloon, the dirigible Number 5. On August 8, 1901 during one of his attempts, his dirigible lost hydrogen gas. It started to descend and was unable to clear the roof of the Trocadero Hotel. A large explosion was then heard. Santos-Dumont survived the explosion and was left hanging in a basket from the side of the hotel. With the help of the crowd he climbed to the roof without injury.

The zenith of his lighter-than-air career came when he won the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize. The challenge called for flying from the Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back in less than thirty minutes. The winner of the prize needed to maintain an average ground speed of at least 22 km/h (14 mph) to cover the round trip distance of 11 km (6.8 miles) in the allotted time.

On 19 October 1901, after several attempts and trials, Santos-Dumont succeeded in using his dirigible Number 6. Immediately after the flight, a controversy broke out around a last minute rule change regarding the precise timing of the flight. There was much public outcry and comment in the press. Finally, after several days of vacillating by the committee of officials, Santos-Dumont was awarded the prize as well as the prize money of 100,000 francs. In a charitable gesture, he donated half of the prize money to the poor of Paris. The other half was given to his workmen as a bonus.

Santos-Dumont's aviation feats made him a celebrity in Europe and throughout the world. He won several more prizes and became a friend to millionaires, aviation pioneers, and royalty. In 1903 Aida D'Acosta Breckinridge piloted Santos Dumont's airship. In 1904, he went to the United States and was invited to the White House to meet U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

The public eagerly followed his daring exploits. Parisians affectionately dubbed him le petit Santos. The fashionable folk of the day mimicked various aspects of his style of dress from his high collared shirts to singed Panama hat. He was, and remains to this day, a prominent folk hero in his native Brazil.

Heavier than air aircraft

Although Santos-Dumont continued to work on dirigibles, his primary interest soon turned to heavier-than-air aircraft. By 1905 he had finished his first airplane design, and also a helicopter. He finally achieved his dream of flying an airplane on 23 October 1906, when, piloting the 14-bis before a large crowd of witnesses, he flew a distance of 60 metres (200 ft) at a height of two to three metres (10 ft). This well-documented event was the first flight verified by the Aero-Club De France of a powered heavier-than-air machine in Europe, and the first public demonstration in the world of an aircraft taking off from an ordinary airstrip with a non-detachable landing gear and under its own power in calm weather, proving to the spectators that a machine "heavier than air" could take off from the ground by its own means. With this accomplishment, he won the Archdeacon Prize founded by the Frenchman Ernest Archdeacon in July 1906, to be awarded to the first aviator to fly more than 25 metres.

On 12 November 1906, Santos-Dumont succeeded in setting the first world record in aviation by flying 220 metres in less than 22 seconds.

Santos-Dumont made other contributions to the field of aircraft design. He added movable surfaces, the precursor to ailerons, between the wings in an effort to gain more lateral stability than was offered by the 14-bis wing dihedral. He also pushed for and exploited substantial improvements in engine power-to-weight ratio, and other refinements in aircraft construction techniques.

Santos-Dumont's final design was the Demoiselle monoplane (Nos. 19 to 22). This aircraft was employed as Dumont's personal transportation and he willingly let others make use of his design. The fuselage consisted of a specially reinforced bamboo boom, and the pilot sat beneath between the main wheels of a tricycle landing gear. The Demoiselle was controlled in flight partly by a tail unit that functioned both as elevator and rudder, and by wing warping (No. 20).

The high-wing Demoiselle aircraft had a wingspan of 5.10 m and an overall length of 8 m. Its weight was little more than 110 kg with Santos-Dumont at the controls. The pilot was seated below the fuselage-wing junction, just behind the wheels, and controlled the tail surfaces using a steering wheel. The cables supporting the wing were made from piano wire. Initially, Santos-Dumont used a liquid-cooled Dutheil & Chalmers engine rated at 20 hp (15 kW). Later, the inventor repositioned the engine to a lower location, placing it in front of the pilot. Santos-Dumont also replaced the former 20 hp (15 kW) engine by a 24 hp (18 kW) Antoniette and carried out some wing reinforcements. This version received the designation No. 20. Due to structural problems and continuing lack of power Santos-Dumont introduced additional modifications in Demoiselle’s design: a triangular and shortened fuselage made of bamboo; the engine was moved back to its original position, in front of the wing; and increased wingspan. Thus, the No. 21 was born. The design of No. 22 was similar to No. 21. Santos-Dumont tested opposed-cylinder (he patented a solution for cooling this kind of engine) and water-cooled engines, with power settings ranging from 20 to 40 hp (30 kW), in the two variants. A feature of the water-cooled variant was the liquid-coolant pipeline which followed the wing lower side lofting to improve aerodynamics.

The Demoiselle airplane could be constructed in only fifteen days. Possessing outstanding performance, easily covering 200 m of ground during the initial flights and flying at speeds of more than 100 km/h, the Demoiselle was the last aircraft built by Santos-Dumont. He performed flights with it in Paris, and made trips to nearby places. Flights were continued at various times through 1909, including the first cross-country flight with steps of about 8 km, from St. Cyr to Buc on 13 September 1909, returning the following day, and another on 17 September 1909 of 18 km in 16 min. The Demoiselle, fitted with a two-cylinder engine, became rather popular. The French World War I ace Roland Garros flew it at the Belmont Park, New York, in 1910. The June 1910 edition of the Popular Mechanics magazine published drawings of the Demoiselle and affirmed that Santos-Dumont's plane was better than any other that had been built to that date, for those who wish to reach results with the least possible expense and with a minimum of experimenting. American companies sold drawings and parts of Demoiselle for several years thereafter. Santos-Dumont was so enthusiastic about aviation that he released the drawings of Demoiselle for free, thinking that aviation would be the mainstream of a new prosperous era for mankind. Clément Bayard, an automotive maker, constructed several units of Demoiselles, which were sold for 50,000 francs.

Controversy vis-à-vis Wright brothers

In Brazil Santos-Dumont is considered to be the inventor of the airplane, because of the official and public character of the 14-bis flight as well as some technical points (see below.)

The Wrights' early aircraft could sustain controlled flight, but always used some sort of assistance to become airborne, requiring a stiff headwind, or the use of launch rails. As such, none of the Wrights' early craft took off under their own power in calm wind from an ordinary ground surface as was achieved by the flights of the 14-bis.

In USA and the UK, the honour of first effective heavier-than-air flight is most frequently assigned to the Wright brothers[1] for their flight of 39 metres (120 ft) in 12 seconds on 17 December 1903 at Kitty Hawk in North Carolina.

Supporters of the Wrights' claim point out that the use of ground rails in particular was necessitated by the Wrights' choice of airfields — the sand at Kitty Hawk and the rough pasture at Huffman prairie — rather than the relatively smooth and firm parkland available to Santos-Dumont and was not a reflection of any aerodynamic weakness in their design. Accordingly, the catapult used at Huffman Prairie allowed the use of a relatively short ground rail thus avoiding the time-consuming drudgery of positioning hundreds of feet of rail needed for launches without a catapult.

The construction of replicas of the original Wright Flyer has exacerbated the controversy in recent years. Many of these replicas used modern aerodynamic knowledge to improve their flight characteristics and still, some just flew. Some replicas failed to fly at public events. However, at least one flying replica was built without being modified. This aircraft, part of the Wright Experience project, through painstaking research of original documents, photographs, and artifacts from the original Flyer, is believed to be an accurate recreation. The Wright Experience project had the stated purpose of building an exact replica of the original aircraft, whether or not it would actually fly. The aircraft did make some successful flights. Meanwhile, most of "14 Bis" made replicas flew without much problem. Those replicas flew as Dumont's plane did.

Much of the controversy about Santos-Dumont and the Wrights arose from the difference in their approaches to publicity. Santos-Dumont made his flights in public, often accompanied by the scientific elite of the time, then gathered in Paris. In contrast, the Wright Brothers were very concerned about protecting what they considered their trade secrets for patentability, and made their first powered flights in a remote location, without international aviation officials present. The defence of their flight was also complicated by the jealousies of other American aviation enthusiasts and disputes over patents. In November 1905, the Aero Club of France learned of the Wrights' reported flight of 24 miles (39 km). They sent a correspondent to investigate the Wrights' accounts. In January 1906, members of the Aero Club of France's meeting were stunned by the reports of the Wrights' flights. Archdeacon sent a taunting letter to the Wrights, demanding that they come to France and prove themselves, but the Wrights did not respond. Thus, the aviation world (of which Paris was the centre at the time) witnessed the products of Santos-Dumont's work first hand. As a result, many members, French and other Europeans, dismissed the Wrights as frauds (like many others at the time) and assigned Santos-Dumont the accolade of the "first to fly".

Early reports of the Wrights' activities and the disclosure by Octave Chanute in 1903 of key design features of their gliders helped European airplane developers.[3] Santos-Dumont's success was aided by improvements in engine power/weight ratio and other advances in materials and construction techniques that he developed in previous years.

There were many machines that got up into the air in a limited fashion and many variations of heavier-than-air titles to which varying amounts of credit have been awarded by various groups. For example, the Frenchman Félix du Temple de la Croix accomplished the first manned powered flight (a short "hop") in 1874.[4] In the former USSR Aleksandr Fyodorovich Mozhaiski is sometimes credited as a "Father of Aviation", for his powered heavier-than-air machine (generally recognized as the second such flight in that category) which flew in 1884.[5] The disputes about the proper definition of "powered heavier than air flight" still go on. For example, with regard to gliders fitted with small engines used non-continuously; these debates do not extend to methods of take off systems. The issue of assisted takeoff can also be an issue with early flights.

The Wright brothers and Dumont demonstrated nearly completely opposite attitudes towards the military use of airplanes. The brothers marketed their aircraft to the U.S. Army for use in war, for reconnaissance they believed, while Santos Dumont in later life abhorred the destructive power of airplanes in warfare.

Wristwatch

The wristwatch had already been invented by Patek Philippe, decades earlier, but Santos-Dumont played an important role in popularizing its use by men in the early 20th century. Before him they were generally worn only by women (as jewels), as men favoured pocket watches.

In 1904, while celebrating his winning of the Deutsch Prize at Maxim's Restaurant in [Paris], Santos-Dumont complained to his friend Louis Cartier about the difficulty of checking his pocket watch to time his performance during flight. Santos-Dumont then asked Cartier to come up with an alternative that would allow him to keep both hands on the controls. Cartier went to work on the problem and the result was a watch with a leather band and a small buckle, to be worn on the wrist.[6]

Santos-Dumont never took off again without his personal Cartier wristwatch, and he used it to check his personal record for a 220 m (730 ft) flight, achieved in twenty-one seconds, on 12 November 1906. The Santos-Dumont watch was officially displayed on 20 October 1979 at the Paris Air Museum next to the 1908 Demoiselle, the last aircraft that he built.

Cartier today has a collection of wristwatches honouring Santos-Dumont called Santos de Cartier. Publicity involved photographs of Santos-Dumont and his achievements.

Later years

Santos-Dumont continued to build and fly airplanes. His final flight as a pilot was made in Demoiselle on 4 January 1910. The flight ended in an accident, but the cause was never completely clear. There were few observers and no reporters on the scene.

Santos-Dumont fell seriously ill a few months later. He experienced double vision and vertigo that made it impossible for him to drive, much less fly. He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. He abruptly dismissed his staff and closed his workshop. His illness soon led to a deepening depression.

In 1911, Santos-Dumont moved from Paris to the French seaside village of Bénerville where he took up astronomy as a hobby. Some of the local folk, who knew little of his great fame and exploits in Paris just a few years earlier, mistook his German-made telescope and unusual accent as signs that he was a German spy who was tracking French naval activity. These suspicions eventually led to Santos-Dumont having his rooms searched by the French military police. Upset by the charge, as well as depressed from his illness, he burned all of his papers, plans, and notes. Thus, there is little direct information available about his designs today.

In 1928 (some sources report 1916), he left France to go back to his country of birth, never to return to Europe. His return to Brazil was marred by tragedy. A dozen members of the Brazilian scientific community boarded a seaplane with the intention of paying a flying welcome to the returning aviator on the luxury liner Cap Arcona. Instead, the seaplane crashed with the loss of all on board. The loss deepened Santos-Dumont's growing despondency.

In Brazil, Santos-Dumont bought a small lot on the side of a hill in the city of Petrópolis, in the mountains near Rio de Janeiro, and in 1918 built a small house there filled with imaginative mechanical gadgetry including an alcohol-fueled heated shower of his own design. He used to spend his summers there to escape the heat in Rio, and affectionately called it A Encantada (The Enchanted), after the road, Rua do Encanto (Street of Enchantment). The stair is designed for easy climbing.

Controversy regarding private life

Santos-Dumont did seem to have a particular affection for a married Cuban-American woman named Aída de Acosta. She is the only person, other than himself, that he ever permitted to fly one of his airships. By allowing her to fly his No. 9 airship she most likely became the first woman to pilot a powered aircraft. Until the end of his life he kept a picture of her on his desk alongside a vase of fresh flowers.

Death

Alberto Santos-Dumont – seriously ill, and said to be depressed over his multiple sclerosis and the use of aircraft in warfare – is believed to have committed suicide by hanging himself in the city of Guarujá in São Paulo, on 23 July 1932. He was buried in the Cemitério São João Batista in Rio de Janeiro. There are many monuments to his work, and his house in Petropolis, Brazil is now a museum. He never married or had any known children.[7]

Legacy

- Santos-Dumont is a small lunar impact crater that lies in the northern end of the Montes Apenninus range at the eastern edge of the Mare Imbrium

- The aviator gives his name to the city of Santos Dumont, in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. In this municipality is located the Cabangu farm, where he was born. The Faculdades Santos Dumont is a group of private higher learning colleges in the city.[8]

- The city of Dumont, in the state of São Paulo, near Ribeirão Preto is so named because it is located where it used to be one the largest coffee farms in the world, between 1870 and 1890. The farm was owned by Alberto Santos-Dumont's father. It was sold in 1896 to a British company, the Dumont Coffee Company.

- The airport for domestic flights of Rio de Janeiro is also named after him (see Santos Dumont Regional Airport)

- The Rodovia Santos Dumont is a highway in the state of São Paulo.

- The Brazilian Air Force (Command of Aeronautics) awards the Santos Dumont Medal of Merit to important personalities in the world of aviation. The state government of Minas Gerais has a similar medal.

- The Réseau Santos-Dumont is a cooperative university network between France and Brazil, instituted by the French and Brazilian Ministries of Education in 1994, with 26 universities in each country.

- The American Office of Naval Research of San Diego, California named one of its research airships as the 600B Santos Dumont.[9]

- The Historic and Cultural Institute of Aeronautics of Brazil has instituted the Santos Dumont Annual Prize of Journalism to the best reports in the media about aeronautics.

- The Lycée Polyvalent Santos-Dumont is a lyceum in Saint-Cloud, France[10]

- Tens of thousands of streets, avenues, plazas, schools, monuments, etc., are dedicated to the national hero in Brazil.

- He is mentioned as a pioneer of aviation, specifically in the area of dirigibles, in the 1984 novel by Robert A. Heinlein entitled Job: A Comedy of Justice.

- The official Brazilian Presidential Aircraft, an Airbus Corporate Jet tail number FAB2101, was named Alberto Santos Dumont.

- A popular Chilean rock band of the 1990s adopted the name Santos Dumont.

- A short story by H.G. Wells, "The Truth About Pyecraft", includes a reference to Santos-Dumont and his skill as an aviator.

- The aviator gives his name to a boutique Aircraft Management and Consultancy Company, Santos Dumont, founded in May 2004 (http://www.santosdumont.com)

See also

- First flying machine

- Airship

- Aviation history

- List of early flying machines

- List of Santos-Dumont aircraft

- List of years in aviation

- History of watches

- History of timekeeping devices

Notes

- ↑ Smithsonian Institution, "The Wright Brothers & The Invention of the Aerial Age";

BBC, "Flying Through the ages" - ↑ The archives of the Dayton Metro Library

- ↑ Alberto Santos-Dumont accessed September 5, 2007.

- ↑ "The first takeoff of a powered, fixed-wing aircraft with a man aboard took place in 1874 at Brest, France. The steam-engine-powered plane, designed by a French naval officer, Félix du Temple, rose a few feet when it was launched down a hill." The New York Times, 2003

- ↑ Mozhaiski, Flying Machines.

- ↑ "Aviation Pioneer Scored A First in Watch-Wearing", New York Times (October 25, 1975, Saturday). Retrieved on 2007-07-21. "Rio de Janeiro (Associated Press) Alberto Santos-Dumont, a pioneer of aviation, once visited Maison Cartier, the Parisian jewelry house."

- ↑ "Alberto Santos-Dumont Lies In State in Brazil's Capital.", New York Times (December 19, 1932, Monday). Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ FESJ - Fundação Educacional São José at www.fsd.edu.br

- ↑ Airship Santos Dumont to Conduct Test Phase at www.news.navy.mil

- ↑ http://www.ac-versailles.fr/etabliss/santos_stcloud/default1.htm

References

- Santos-Dumont, Alberto (1973). My Airships. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-22122-9.

- Winters, Nancy (1997). Man Flies — The Story of Alberto Santos-Dumont. Ecco Press. ISBN 0-88001-636-1.

- Wykeham, Peter (1962). Santos-Dumont — A Study in Obsession. Harcourt, Brace & World. ISBN 0-405-12210-1.

- Hoffman, Paul (2003). Wings of Madness: Alberto Santos-Dumont and the Invention of Flight. Hyperin Press. ISBN 0-7868-6659-4.

- Bento Mattos Santos Dumont and the Dawn of Aviation , AIAA paper # 2004-106, 42nd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, Jan. 2004 [1]

- Bento Mattos Short History of Brazilian Aeronautics , AIAA paper # 2006-328, 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, Jan. 2006 [2]

- Waugaman, Elisabeth P. (2005). Follow Your Dreams: The Story of Alberto Santos-Dumont/ Dê Asas aos Seus Sonhos ((for children ages 6-12, bilingual, Portuguese/English) ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Prometheus Press. ISBN 85-99240-02-1.

- Henrique Lins de Barros (2006) (PDF). Santos-Dumont and the Invention of the Airplane. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Ministry of Science & Technology and the Brazilian Centre for Research in Physics. ISBN 85-85752-17-3. http://www.cbpf.br/Publicacoes/SantosDumontINGLES.pdf.

External links

- Santos Dumont motorized skis

- Early Aviators Website — A good site for further information about early aviation.

- Photograph of the 14-bis

- Centennial of flight Commission

- Flight simulation and movie

- Wings of Madness Review of the biography of Santos-Dumont by Paul Hoffman.

- PBS TV program Nova, "Wings of Madness" transcript

- U. S. Centennial of Flight Commission Dumont

- First to Fly and Santos Dumont

- Wright stuff or myth that grew wings?

- Alberto Santos Dumont Article by writer Patricia Nell Warren.

- History of Aviation: Brazil. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

- Santos-Dumont's house in Petropolis

- What I Saw and What We Will See Book written by Santos-Dumont in 1918 about his heavier-than-air work, controversy vis-à-vis the Wrights, and predictions for the future. The original title is O que eu vi, o que nós veremos. In Portuguese.

- Aero Club de France's site (in French)

- Nova

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Santos-Dumont, Alberto |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Aviation pioneer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 20 1873 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Santos Dumont, Minas Gerais |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 23 1932 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Guarujá, São Paulo |