Sale, Greater Manchester

| Sale | |

|

|

|

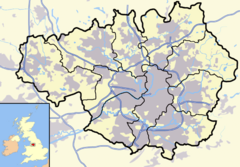

Sale shown within Greater Manchester |

|

| Population | 55,234 (2001 census) |

|---|---|

| - Density | 12,727 per mi² (4,914 per km²) |

| OS grid reference | |

| - London | 162 mi (261 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | Trafford |

| Metropolitan county | Greater Manchester |

| Region | North West |

| Constituent country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SALE |

| Postcode district | M33 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| European Parliament | North West England |

| UK Parliament | Altrincham and Sale West |

| Wythenshawe and Sale East | |

| List of places: UK • England • Greater Manchester | |

Sale (pop. 55,234) is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, in Greater Manchester, England, 5.2 miles (8.4 km) southwest of Manchester City Centre. It lies on flat ground beside the Bridgewater Canal and the River Mersey, which forms its northern boundary with Stretford. The town borders Altrincham to the south and the city of Manchester to the east. Local areas include Brooklands, Sale Moor, and Ashton upon Mersey, which was a separate district until 1930.

Sale was historically a part of Cheshire. The name first appears at around the turn of the 13th century, but the settlement is thought to be much older, possibly dating from the 7th or 8th centuries, during the Anglo-Saxon period. Evidence of Stone Age and Roman activity has been discovered in the town and its surroundings. Until the Industrial Revolution, agriculture was the main source of employment in the town. The arrival of the railway in the mid-19th century led to an influx of middle class residents and to Sale's growth as a commuter town. Although agriculture subsequently declined, other sectors such as the service industry expanded. The town's population growth resulted in it being granted borough status in 1935. In 1974, Sale became part of the newly created Metropolitan Borough of Trafford. It continues to thrive as a commuter town, but also has its own retail, real estate and business sectors. Sale is served by three stations along the Manchester Metrolink, and has access to the motorway network.

Two of the town's main attractions are the Sale Water Park, which contains an artificial lake used for water-sports, and the Waterside Arts Centre. Sale Sharks, a Premiership rugby union club, was founded in Sale but is now based in Stockport. Sale Harriers Manchester Athletics Club also began in Sale but later moved to Wythenshawe. Notable past and present residents include physicist James Joule, singer David Gray, and Sale Harriers athletes Darren Campbell and Diane Modahl.

Contents |

History

The town has a long history, with settlement from at least the 12th century and human activity in the area since the Stone Age. The only evidence of prehistoric activity in Sale comes from the discovery of a flint arrowhead.[1] No other archaeological evidence of human activity in the area has been found until the Roman period. Sale lies on the line of the Roman road between the fortresses at Chester (Deva Victrix) and York (Eboracum) via the fort at Manchester (Mamucium).[2] The A56 road follows the line of the Roman road through the town.[1] A 4th-century Roman hoard of 46 coins was discovered in Ashton upon Mersey (a settlement now part of Sale), one of four known hoards dating from that period discovered within the Mersey basin.[2][3] In the 18th century it was thought that Ashton upon Mersey might be the site of a Roman station next to the River Mersey called Fines Miaimae & Flaviae; however, this was based on the De Situ Britanniae, a manuscript forged by Charles Bertram, and there is no evidence to suggest a station existed there.[4]

After the Romans left Britain in the early-5th century, Britain was inhabited by the Anglo-Saxons. The name Sale, which probably dates from the 7th or 8th centuries,[5] comes from the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) word seale meaning "at the sallow tree".[6] The name Ashton is Old English for "village or farm near the ash trees", suggesting that Ashton upon Mersey is also of Anglo-Saxon origin.[7] Other evidence for the town's origin includes road and field names; for example, Dane Road and Fairy Lane probably derive from the Anglo-Saxon denu, meaning a valley, and faer, meaning a road.[8] Although the townships of Sale and Ashton upon Mersey were not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, this may be because only a partial survey was taken.[9] The first recorded occurrence of Sale is in 1199–1216,[6] in a deed referring to a land grant. That Sale is referred to as a township rather than a manor suggests that the settlement may date back to the Anglo-Saxon period; townships were a Saxon development and were generally replaced by, or incorporated into, less democratic manors after the Norman conquest of England.[10] Ashton upon Mersey is first mentioned in 1260.[6]

William FitzNigel, a powerful 12th-century baron in north Cheshire, held thirty manors including that of Sale, which he divided between Thomas de Sale and Adam de Carrington, De Sale and de Carrington acted as lords of the manor on FitzNigel's behalf.[11] On de Sale's death, his land passed to his son-in-law, John Holt; de Carrington's land passed into the ownership of Richard de Massey, a member of the Masseys who were barons of Dunham. Sale descended through the Holt and Massey families until the 17th century, when the lands were sold.[11] Sale Old Hall was built c. 1603 for James Massey, probably to replace a medieval manorial hall.[12] The earliest phase of the hall was of brick construction and was built just as brick as a building material came into use in north-west England.[13] It was rebuilt in 1840 and demolished in 1920, but two buildings in its grounds have survived: its dovecote and its lodge, the latter now used by Sale Golf Club.[12]

Sale is linked to Stretford in the north by Crossford Bridge, over the River Mersey. The original bridge dated back to at least 1367.[14] The bridge was torn down in 1745 due to the Jacobite rising as the government ordered that all bridges across the river be destroyed, in an effort to slow the Jacobite advance. When the Jacobites reached Manchester they repaired Crossford Bridge and used it to send a small force into Sale and Altrincham, in an effort to deceive the government into believing that their objective was Chester. The feint was successful and the Jacobites later marched south through Cheadle and Stockport instead.[15]

The Runcorn extension of the Bridgewater Canal was completed in 1765, financed by the Duke of Bridgewater to send coal from his mines in Worsley to the mouth of the River Mersey. The opening of the extension in 1776[16] changed Sale's economy by providing a quick and cheap route for fresh produce into Manchester.[16] Farmers who took their wares to market in Manchester brought back night soil to fertilise the fields.[17] However, not everyone benefited from the canal. Several yeomen claimed that their crops were damaged by flooding from the Barfoot Bridge aqueduct.[18] A map from 1777 shows a village named Cross Street, divided between the townships of Sale and Ashton upon Mersey, on the site of the road now of that name.[19] The village was first referred to in 1586 and is believed to have originated in this time.[20] The 1777 map also shows that the village of Sale was spread out, mainly consisting of farmhouses around Dane Road, Fairy Lane, and Old Hall Road.[19] As Sale expanded, Cross Street was absorbed into it.

In 1807, about 300 acres (120 ha) of "wasteland" known as Sale Moor was enclosed, to be divided between the landowners in Sale.[21] As a result, those who had used the land as pasture were left without a source of income and had to look for work elsewhere, such as in the city or work houses.[22] The region experienced an economic depression during the early-19th century; records of poor relief in the town start in 1808.[23] Poorhouses, where paupers could stay rent free, were built in the early-19th century, reflecting the poor state of the local economy.[24] In 1829, Samuel Brooks acquired 515 acres (208 ha) – about a quarter of the township – from George Grey, 6th Earl of Stamford.[25]

The Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway (MSJ&AR) opened in 1849,[26] and led to the middle classes using Sale as a commuter town – a residence away from their place of work.[27] This resulted in Sale's population more than tripling by the end of the century.[28] "Villas" were built in Sale Moor, and a few in Ashton upon Mersey, as the new middle classes' demand for land increased.[29] Pressure from an increased population led to the town to be supplied with amenities such as sewers, which were first built in 1875–80;[30] Sale was connected to the telephone network in 1888.[31] As in the late-19th century, the early-20th century saw a lot of construction work in Sale. The town's first cinema, The Palace, was opened during the First World War,[32] and the first swimming baths were built in 1914.[33] The end of the war in 1918 resulted in a rush of marriages, which highlighted a shortage of housing. The local councils of Sale and Ashton upon Mersey took the initiative of building council housing, houses owned by the council and rented to the local population at below market rates. A housing estate, Woodhey's Hall, was built in Ashton upon Mersey in 1931,[34] and by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Sale had 594 council houses.[35]

The new housing that was being built in the early-20th century was interrupted by the start of the Second World War.[33] Sale was never officially evacuated during the war, and even received some families from evacuated areas although it was not considered far enough from likely targets to be an official destination for evacuees.[36] In the event, the town did experience some bombing due to its proximity to Manchester, a centre of industry directed towards the war effort. Incendiary bombs were dropped on Sale in September 1940 with no casualties, although a house was damaged. In a bombing incident the following November, four people were injured and a school was damaged; on 22 December 1940 twelve people were injured by bombs.[36] On the night of 23 December much of Manchester suffered heavy bombing in what became known as the Manchester Blitz. Six hundred incendiary bombs were dropped on Sale in three hours. There were no injuries, but Sale Town Hall was severely damaged.[36]

Sale recovered from the Second World War, and in the 1960s underwent some regeneration with the redevelopment of its shopping centre.[33] In 1973 the centre of Sale, the shopping precinct which had developed since the mid-19th century, was redeveloped and pedestrianised in an attempt to increase trade.[33] The construction of the M63 motorway in 1972 led to the creation of Sale Water Park. An embankment was required for the motorway and the area from which the material for this was taken was flooded and turned into an artificial lake and water-sports centre.[37] Opportunities for leisure were increased when the old swimming baths, which were demolished in 1971, were replaced in 1973 by a new complex built on the same site.[33] Sale became part of the newly formed Borough of Trafford in 1974.[33]

Governance

- Further information: Municipal Borough of Sale

Historically, Sale was a township in the Cheshire parish of Ashton upon Mersey. The township adopted the Local Government Act 1858 in November 1866, and Sale Local Board was formed to govern the town at the beginning of 1867.[38] Under the Local Government Act 1888 Sale became a district of the administrative county of Cheshire. It was replaced by Sale Urban District in 1894. The parish of Ashton upon Mersey became an urban district in 1895.[39] In 1930 Ashton upon Mersey UD was merged into Sale UD,[40][39] and in 1935 the new, larger Sale UD became a municipal borough.[39] In 1974, the borough was abolished and Sale became part of the newly created Metropolitan Borough of Trafford in Greater Manchester.[33][39]

For national elections, Sale was in the parliamentary constituency of Altrincham and Sale from 1945 until 1997, when it was split between Altrincham and Sale West and Wythenshawe and Sale East. The Altrincham and Sale West constituency is not only one of the Conservative Party's few seats in North West England but also the only Conservative seat in Greater Manchester.

Sale is in the local government district of Trafford, and its education, town planning, waste collection, health, social care and other services are administered by Trafford Council.[41] The Sale area consists of five electoral wards, which between them have 15 of the 63 seats on the council. They are Ashton upon Mersey, Brooklands, Priory, Sale Moor, and St. Mary's.[42] As of the 2008 local elections, the Conservative Party held ten of the seats and the Labour Party five.[43]

Geography

- Further information: Geography of Greater Manchester and Climate of Greater Manchester

At (53.4246, -2.322), the town lies north of the town of Altrincham, to the south of the town of Stretford and 5.2 miles (8 km) to the southwest of Manchester City centre. The district of Wythenshawe is to the southeast.

Sale is located in the Mersey Valley, about 100 feet (30 m) above sea level. The River Mersey, just north of the town,[1] is prone to flooding during heavy rains, so the Sale Water Park, close to the town's northern boundary, acts as an emergency flood basin.[44] The man-made, and thus more controllable, Bridgewater Canal runs through the centre of the town.

Sale's local geology consists of sand and gravel deposited about 10,000 years ago, during the last ice age.[45] The bedrock is Bunter sandstone in the west and Triassic waterstone in the east.[46] United Utilities obtains the town's drinking water from the Lake District.[47]

Ashton upon Mersey, Sale Moor in the southeast, and Brooklands in the southwest are the town's main districts. The main commercial neighbourhood is Sale town centre, in the central northern area of the town, but smaller commercial centres are also found in Ashton upon Mersey and Sale Moor. Brooklands is the most densely populated area. Parks are mainly located in the central and southern areas, as Ashton upon Mersey and Sale Moor suffer from a lack of accessible green space.[48][49][50]

Sale's climate is generally temperate, like the rest of Greater Manchester. The mean highest and lowest temperatures are slightly above the national average (12.1 °C (53.8 °F) and 5.1 °C (41.2 °F)), while the annual rainfall and average hours of sunshine are respectively above and below the national average (806.6 millimetres (31.76 in) and 1457.4 hours).[51][52]

Demography

- Further information: Demography of Greater Manchester

| Sale Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Sale[53] | Trafford[54] | England |

| Total population | 55,234 | 210,145 | 49,138,831 |

| Foreign born | 6.7% | 8.2% | 9.2% |

| White | 95.1% | 89.7% | 91% |

| Asian | 1.9% | 4.6% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.7% | 2.3% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 78% | 76% | 72% |

| Muslim | 1.4% | 3.3% | 3.1% |

| No religion | 13% | 12% | 15% |

| Over 65 years old | 17% | 16% | 16% |

As of the 2001 UK census, Sale had a population of 55,234. The 2001 population density was 12,727 per mi² (4,914 per km²), with a 100 to 94.2 female-to-male ratio.[55] Of those over 16 years old, 30.0% were single (never married) and 51.3% married.[56] Sale's 24,027 households included 32.2% one-person, 37.8% married couples living together, 8.3% were co-habiting couples, and 8.5% single parents with their children, these figures were similar to those of Trafford and England.[57] Of those aged 16–74, 22.3% had no academic qualifications, similar to that of 24.7% in all of Trafford but significantly lower than 28.9% in all of England.[58][54] Sale had a much higher percentage of adults with a diploma or degree than Greater Manchester as a whole. 26.7% of Sale residents aged 16–74 had an educational qualification such as first degree, higher degree, qualified teacher status, qualified medical doctor, qualified dentist, qualified nurse, midwife, health visitor, etc. compared to 20% nationwide.[54][59]

Originally a working class town, there was an influx of middle class people in the mid-19th century when businessmen used Sale as a commuter town.[27] Since then, Sale has had a greater proportion of middle class people than the rest of England. In 1931, 22.7% of Sale's population was middle class compared with 14% in England and Wales, and by 1971, this had increased to 36.3% compared with 24% nationally. Parallel to this increase in the middle classes of Sale was the decline of the working class population. In 1931, 20.3% were working class compared with 36% in England and Wales; by 1971, this had decreased to 15.4% in Sale and 26% nationwide. The rest of the population was made up of clerical workers and skilled manual workers. The change in social structure in the town was at a similar rate to that of the rest of the nation but was biased towards the middle classes, making Sale the middle class town it is today.[60]

Population change

As recorded in the hearth tax returns of 1664, the township of Sale had a population of about 365.[61] Parish registers show that the area experienced a steadily growing population during the 17th and 18th centuries, increasing during the 19th century, influenced by the Industrial Revolution. Although Sale's population greatly increased in the 19th century, it did so less rapidly than that of Altrincham, Bowdon, or Stretford.[62] Sale's most significant population growth occurred in the second half of the 19th century, when the settlement grew as a commuter town following the arrival of the railway.[63] The huge increase in population between 1921 and 1931 is accounted for by Ashton upon Mersey's administrative merger with Sale in 1930.[64] The decrease in the town's population since the 1981 census follows the population trend for Trafford and Greater Manchester; this has been accounted for by the decline of Greater Manchester's industries, including those in Trafford, and residents leaving, seeking new jobs.[65] The table below details the population change since 1801, including the percentage change since the last census.

| Population growth in Sale since 1801 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 |

| Population | 819 | 901 | 1,049 | 1,104 | 1,309 | 1,720 | 3,031 | 5,573 | 7,916 | 9,644 | 12,088 | 15,044 | 16,329 | 28,071 | 38,911 | 43,168 | 51,336 | 55,749 | 57,824 | 56,052 | 55,234 |

| % change | – | +10.0 | +16.4 | +5.2 | +18.6 | +31.4 | +76.2 | +83.9 | +42.0 | +21.8 | +25.3 | +19.6 | +8.5 | +71.6 | +38.6 | +10.9 | +18.9 | +8.6 | +4.4 | −3.1 | −1.5 |

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time[28][64][66] | |||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

| Sale Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK Census | Sale[67] | Trafford[68] | England |

| Population of working age | 40,272 | 151,445 | 35,532,091 |

| Full time employment | 45.5% | 43.4% | 40.8% |

| Part time employment | 11.6% | 11.9% | 11.8% |

| Self employed | 7.8% | 8.0% | 8.3% |

| Unemployed | 2.5% | 2.7% | 3.3% |

| Retired | 14.3% | 13.9% | 13.5% |

During the medieval period, most of the area was used for agriculture; this consisted of growing crops and raising livestock such as cattle.[69] The arable farming would have been enough for the local populace to live on, but the cattle would have been sold to the ruling classes.[70] Agriculture remained the main employer in Sale the mid-19th century; this was the case for most of what would become Trafford, partly because of a reluctance to invest in industry on the part of the two main land owners in the area: the Stamfords and the de Traffords.[71] Although weaving was common in Sale during the late 17th and early 18th century, by 1851 only 4% of the population was employed in that industry.[72]

Along with the rest of the region the economy of Sale in the early-19th century was weak, and small farmers and businessmen were frequently bankrupted; this continued until the arrival of the railway in the mid-19th century.[24] Despite the dominance of agriculture, there was a growing service industry; Sale and Ashton upon Mersey experienced a growth in numbers employed in retail and domestic services in the first half of the 19th century.[63] By 1901, less than 20% of Sale residents were employed in agriculture.[63] Employment was available in work houses for those who could not find work elsewhere. Sale was part of the Altrincham Union, which ran the nearest work house, in Altrincham.[73]

The main shopping centre in Sale, the Square Shopping Centre, was constructed in the 1960s. With the Trafford Centre's opening in 1998, it was expected that the centre would suffer, however the area has since prospered.[74] In 2003 the Square Shopping Centre underwent a £7M refurbishment and was sold for £40M in 2005; it was a major part of the redevelopment of Sale's town centre. The square experienced an increase in trade and demand for tenancy in the square led to an increase of 70% in rents.[75] The Square Shopping Centre received less funding than the redevelopment of the shopping centre in Altrincham, £7M compared to Altrincham's £40M.[76] Sale's economy has progressed to the extent that in 2007, when the rest of south Manchester oversupplied with office space, Sale's available office and commercial space was at an all time low because of high demand.[77]

According to the 2001 UK census, the industry of employment of residents aged 16–74 was 18.4% property and business services, 15.9% retail and wholesale, 11.1% manufacturing, 10.9% health and social work, 9.1% education, 7.8% transport and communications, 6.1% construction, 6.3% finance, 4.5% public administration, 3.8% hotels and restaurants, 0.5% agriculture, 0.7% energy and water supply, and 4.7% other. Compared with national figures, the town had a relatively high percentage of residents working in property, business services and finance. The town had a relatively low percentage working in agriculture, public administration and manufacturing.[78] The census recorded the economic activity of residents aged 16–74, 2.6% students were with jobs, 3.3% students without jobs, 4.9% looking after home or family, 5.2% permanently sick or disabled, and 2.3% economically inactive for other reasons.[67] The 2.4% unemployment rate of Sale area was low compared with the national rate of 3.3%.[68]

Culture

Landmarks and attractions

Sale has three Grade II* listed buildings, including two churches and Ashton New Hall, and 18 Grade II listed buildings.[79] The oldest surviving building in Sale is Eyebrow Cottage.[80] Originally a yeoman farmhouse built around 1670, it is one of the earliest brick buildings in the area. Its name is derived from the decorative brickwork above the windows. It was built in Cross Street, which at the time was a separate village from Sale.[19]

The cenotaph outside the town hall was designed by Ashton upon Mersey sculptor A. Sherwood Edwards and is a Grade II listed building.[79] It commemorates the 400 men from Sale who died in the First World War and the 300 who died in the Second World War. Sale Water Park is an artificial lake, created from a 35-metre (115 ft) deep gravel pit left during the construction of the M60. It opened in 1980 and is a venue for water sports, fishing and bird watching. The water park is the site of the Broad Ees Dole wildlife refuge, a Local Nature Reserve that provides a home for migratory birds.[81]

Cultural events and venues

The Waterside Arts Centre, opened in 2004, is Sale's cultural centre. Situated next to the town hall, it includes a plaza, a library, the Robert Bolt Theatre, the Lauriston Gallery, and the Corridor Gallery. The centre regularly hosts concerts, exhibitions and other community events. Performers have included Midge Ure, Fairport Convention, The Zombies and Sue Perkins. Opportunities are also provided for local bands and artists to promote their work.[82] In 2004, the centre received the British Urban Regeneration Association Award for its innovative use of space and for reinvigorating Sale town centre.[83]

Sale has a Gilbert and Sullivan society, formed in 1972, which performs at the Altrincham, Garrick Playhouse. The group is directed by Alistair Donkin, a former principal comic for the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. Members of the group have won several awards at The International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival.[84] Sale Brass is a traditional brass band based in Sale, formed in about 1849 as the Stretford Temperance Band. Its first reported performance was at the 1849 opening of the railway between Manchester and Altrincham. The band is currently ranked in the 4th Section of the brass band movement.[85]

Sports

The rugby union side Sale F.C. has been based in Sale since 1861 and at its present Heywood Road ground since 1905. Sale F.C. is one of the oldest rugby clubs in the world and is still based in the town. Its 1865 Minute Book is the oldest existing book containing the rules of the game.[86] The professional Sale Sharks team was originally part of Sale F.C. but split from it in 2003. Sale Sharks now play their matches in Stockport although they use Heywood Road as a training ground.[87] The town is also home to the Ashton upon Mersey Rugby Union Club and the Trafford Metrovick Rugby Union Club.[88][89]

Sale Harriers Manchester Athletics Club was formed in 1911, but is now based in nearby Wythenshawe. The club has produced successful athletes such as Olympic gold medallist Darren Campbell. Sale Sports Club encompasses Sale Cricket Club, Sale Hockey Club and Sale Lawn Tennis Club.[90] The Brooklands Sports Club is home to Brooklands Cricket Club, Brooklands Manchester University Hockey Club and Brooklands Hulmeians Lacrosse Club. It also provides facilities for squash, tennis and bowling. Sale United FC plays at Crossford Bridge and was recognised as Trafford’s Sports Club of the Year in 2004. Sale Golf Club and Ashton on Mersey Golf Club have courses on the outskirts of the town,[91] and a municipal Pitch and Putt based at Woodheys Park,[92] Trafford Rowing Club has a boathouse beside the canal.[93] The Sale Leisure centre has three swimming pools, badminton and squash courts, and a gymnasium.[94] The Walton Park Sports Centre has a sports hall for activities such as 5-a-side football, karate and table-tennis.[95] Tennis, crown-green bowls, golf putting and football facilities are available at the town's parks.

Education

- Further information: List of schools in Trafford

Sale's first school was built in 1667, but it fell out use in the first half of the 18th century.[96] By the 19th century, there were two private schools in Sale and one in Ashton upon Mersey. There were also four Sunday schools in Sale and one in Ashton upon Mersey, operated by religious denominations.[97] Education became compulsory in 1870, but students initially had to pay a fee; in 1872, compulsory education became freely available.[97]

Trafford maintains a selective education system assessed by the Eleven Plus exam. Sale has one grammar school, two secondary modern schools and nineteen primary schools. Sale Grammar School a specialist school in the visual arts;[98] was described in its 2006 Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (OFSTED) report as "outstanding with an outstanding sixth form."[99] Ashton on Mersey School is a foundation secondary modern school and specialist sports college.[100] Sale High School, formerly Jeff Joseph Sale Moor Technology College, is a foundation secondary modern school and specialist technology college.[101] Manor High School provides secondary education to pupils with special needs.[102]

Religion

- See also: List of churches in Greater Manchester

Sale is a diverse community with a synagogue and Christian churches of various denominations. The church buildings were mostly constructed in the late 19th or early 20th century in the wake of the population boom created by the arrival of the railway in 1849,[103] although records show that the Church of St Martin in Ashton upon Mersey (which became part of Sale in the 1930s), dates back to at least 1304.[104] Before the English Reformation, the inhabitants of Sale were predominantly Catholic, but afterwards were members of the Church of England. Roman Catholics returned to the area in the 19th century in the form of Irish immigrants.[103] An early 20th-century booklet was published detailing a medieval priory in Sale; however there was no such priory in the town as the locations of all 11 religious houses in Cheshire at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1541) were know, and no religious order owned any land in the township.[105]

Two of the three Grade II* listed buildings in the town are churches. The Church of St Martin, which was probably originally an early 14th-century timber framed structure, was rebuilt in 1714 after the church had been destroyed in a storm.[106][107] The Church of St John the Divine was built in 1868 and designed by Alfred Waterhouse.[108] There are three Grade II listed churches in Sale: the Church of St Anne; the Church of St Mary Magdalene; and the Church of St Paul.[79] As of the 2001 UK census, 78.0% of Sale residents reported themselves as being Christian, 1.4% Muslim, 0.7% Hindu, 0.6% Jewish, 0.2% Buddhist and 0.2% Sikh. The census recorded 12.9% as having no religion, 0.2% had an alternative religion and 5.9% did not state their religion.[109] Sale is part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Shrewsbury,[110] and the Church of England Diocese of Chester.[111] Sale and District Synagogue is on Hesketh Road in Sale.[112] It is part of United Synagogue and is under the aegis of the Chief Rabbi of Britain, Jonathan Sacks.[113] The only mosque in Trafford is the Masjid-E-Noor in Old Trafford.[114]

Transport

The opening of the Bridgewater Canal in 1776 made commuting from Sale into Manchester practical and convenient via the "swift packet", which travelled at 10 mph (16 km/h).[115] Commuting became even more practical in 1849, with the opening of the Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway (MSJ&AR), which ran north–south through Sale. The one station in the town, originally named Sale Moor,[26] was renamed Sale in 1856.[116] Brooklands station was added to the line in 1859, and Dane Road in 1931, when the line was electrified in one of the first such projects outside of South East England.[117] The line was renovated in the early 1990s and is now part of the Metrolink.[117]

The Metrolink tram or light rail service connects Sale with other locations in Greater Manchester. Trams leave from the town's three stations every six minutes between 7:15 am and 6:30 pm, and every 12 minutes at other times of the day.[118] The nearest main line railway station is Navigation Road in Altrincham, from where trains run to Manchester Piccadilly, Stockport and Chester. Bus routes operated by various companies provide services to Manchester and Altrincham.[119] The A56 road runs between Chester and North Yorkshire via Sale, Manchester, and Burnley,[1] and the M60 motorway – which encircles Manchester – can be accessed via junction 7, just to the north of Sale. The M56 and M62 motorways are about 4 miles (6 km) away, and the M6 motorway, which runs between Warwickshire and Carlisle, is about 7 miles (11 km) to the west. Manchester Airport, the busiest airport in the UK outside London,[120] is 4 miles (6 km) to the south.

Notable people

James Joule, the physicist who gave his name to the SI unit of energy, lived in Sale all his life. Joule died at his home at 12 Wardle Road and is buried in Brooklands Cemetery. The "J.P. Joule" public house is named after him and there is a bust of him in Worthington Park.[121] The authors Robert Bolt[122] and Peter Tinniswood[123] were brought up in Sale. The left-wing Member of Parliament and cabinet minister Baron Orme was born in the town.[124] The singer-songwriter David Gray lived in Sale until moving to Wales at age nine.[125] Radio presenter Marc Riley, the former host of the BBC Radio 1 Breakfast show, lived in Sale.[126] Olympic Games gold medalist Darren Campbell[127][128] and Commonwealth Games gold medalist Diane Modahl[129] lived in Sale and trained at Sale Harriers Manchester Athletics Club. Several members of Lancashire County Cricket Club have resided in the town, most notably the England player Cyril Washbrook.[130]

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Swain (1987), p. 9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nevell (1997), p. 20.

- ↑ Nevell (1992), pp. 59, 75.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Kenyon (1989), pp. 38–39

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Nevell (1997), p. 32.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 12.

- ↑ Redhead, Norman, in: Hartwell, Hyde and Pevsner (2004), p. 18.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 11.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Swain (1987), p. 20.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Swain (1987), p. 22.

- ↑ Nevell (2008), p. 61.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 27.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 42, 44.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Swain (1987), p. 44.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 47.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 44–45.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Swain (1987), p. 40.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), p. 56

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 52.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 61.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 61–62.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Swain (1987), p. 68.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 59.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Nevell (1997), p. 97.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Swain (1987), p. 85.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Nevell (1997), p. 87.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 91.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 116.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 84.

- ↑ Swain (1987) p. 112.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 Swain (1987), p. 134.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 126.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 119, 123.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Swain (1987), p. 133.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 135–136.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 23204, page 24, 1 January 1867. Retrieved on 12 August 2008.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Youngs (1991), pp. 6, 33, 644–646

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 119.

- ↑ Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council. "Trafford Council Constitution 2007". Trafford.gov.uk. Retrieved on 6 January 2008.

- ↑ "Wards in Trafford". Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council (2007). Retrieved on 17 April 2007.

- ↑ "Local election results 2008". Trafford.gov.uk. Retrieved on 1 August 2008.

- ↑ "Exploring Greater Manchester" (PDF). Manchester Geographical Society (1998). Retrieved on 6 May 2007.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), p. 1.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), p. 3.

- ↑ "Drinking water quality report". United Utilities. Retrieved on 30 June 2007.

- ↑ "Brooklands Ward Profile". Trafford Council (2007). Retrieved on 30 June 2007.

- ↑ "Ashton-on-Mersey Ward Profile" (PDF). Trafford Council (2007). Retrieved on 30 June 2007.

- ↑ "Sale Moor Ward Profile" (PDF). Trafford Council (2007). Retrieved on 30 June 2007.

- ↑ "Manchester Airport 1971–2000 weather averages". Met Office (2001). Retrieved on 12 August 2008.

- ↑ Met Office (2007). "Annual England weather averages". Met Office. Retrieved on 23 April 2007.

- ↑ "KS06 Ethnic group: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (25 January 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 "Trafford Metropolitan Borough key statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS01 Usual resident population: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (7 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS04 Marital status: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS20 Household composition: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

•"Trafford Metropolitan Borough household data". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved on 5 August 2008. - ↑ "KS13 Qualifications and students: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS13 Qualifications and students: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas" (7 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "Sale social class". Vision of Britain. Retrieved on 1 August 2008.

•"Percentage of Working-Age Males in Class 1 and 2". Vision of Britain. Retrieved on 1 August 2008.

•"Percentage of Working-Age Males in Class 4 and 5". Vision of Britain. Retrieved on 1 August 2008. - ↑ Nevell (1997), p. 59.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), p. 85.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Nevell (1997), p. 86.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Swain (1987), p. 139.

- ↑ "Trafford Metropolitan Borough key statistics" (PDF). audit-commission.gov.uk. Retrieved on 22 February 2008.

- ↑ Greater Manchester Urban Area, United Kingdom Census 1991, http://www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/greater_manchester_urban_area.asp Retrieved on 30 October 2008.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 "KS09a Economic activity - all people: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (3 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Trafford Local Authority economic activity". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved on 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 15.

- ↑ Swain (1987), pp. 14, 16.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), pp. 85–86, 88–91.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 61.

- ↑ "'Bright future' for town centre". Manchester Evening News (25 September 2002). Retrieved on 28 August 2008.

- ↑ David Thame (22 November 2005). "Sale shops fetch £40m". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved on 20 August 2008.

- ↑ Dean Kirby (16 November 2005). "£40m new look for shops centre". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved on 20 August 2008.

- ↑ Dean Kirby (20 November 2007). "Sale's sales boom". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved on 23 August 2008.

- ↑ "KS11a Industry of employment - all people: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (3 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 "Planning and building control: listed buildings" (PDF). Trafford MBC. Retrieved on 31 July 2008.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), pp. 2, 77–8.

- ↑ "Broad Ees Dole". Mersey Valley Countryside Warden Service. Retrieved on 27 April 2007.

- ↑ "Take a trip to Sale Waterside". Trafford.gov.uk. Retrieved on 1 August 2008.

- ↑ "Economic regeneration: Trafford Metropolitan Borough". Audit Commission. Retrieved on 1 August 2008.

- ↑ "Sale Gilbert and Sullivan Society". SaleGASS.org.uk. Retrieved on 11 June 2007.

- ↑ "Sale Brass". salebrass.co.uk. Retrieved on 28 March 2008.

- ↑ "Sale F.C.". Sale F.C.. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ John Gardiner. "Sale FC history". Salefc.com. Retrieved on 12 April 2007.

- ↑ "Ashton-on-Mersey RUFC contact details". Ashton-on-MerseyRUFC.co.uk. Retrieved on 28 August 2008.

- ↑ "A brief history of Trafford MV". TraffordMV.co.uk. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Sale Sports Club". Sale Sports Club. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Ashton on Mersey Golf Club". English Golf Courses. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Woodheys park pitch and putt". Friends of Woodheys Park. Retrieved on 26 April 2008.

- ↑ "Welcome to Trafford Rowing Club". Trafford Rowing Club. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Sale Leisure Centre". Trafford Community Leisure Trust. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Walton Park Sports Centre". Trafford Community Leisure Trust. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 69

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Swain (1987), p. 73.

- ↑ "Sale Grammar School". Specialist School and Academies Trust. Retrieved on 3 February 2008.

- ↑ "Sale Grammar School 2006 Ofsted Report" (PDF). Sale Grammar School (22 November 2006). Retrieved on 2 May 2007.

- ↑ "Ashton upon Mersey School". Ashton upon Mersey School. Retrieved on 2 May 2007.

- ↑ "Sale High School". Sale High School. Retrieved on 2 May 2007.

- ↑ "Manor High School". Trafford Council. Retrieved on 2 May 2007.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Swain (1987), p. 76.

- ↑ Nevell (1997), p. 28.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 37.

- ↑ "Church of Martin, Sale". Images of England. Retrieved on 23 February 2008.

- ↑ Richards (1947), pp. 22–24.

- ↑ "Church of John the Divine, Sale". Images of England. Retrieved on 23 March 2008.

- ↑ "KS07 Religion: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Statistics.gov.uk (2 February 2005). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "Catholic Diocese of Shrewsbury". DioceseofShrewsbury.org. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "The Church of England Diocese of Chester". Chester.Anglican.org. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Sale Synagogue". Trafford.gov.uk. Retrieved on 12 August 2008.

- ↑ "List of United Synagogues across the UK". somethingjewish.co.uk. Retrieved on 14 August 2008.

- ↑ "Trafford community groups search". Trafford.gov.uk. Retrieved on 12 August 2008.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 46.

- ↑ Swain (1987), p. 89.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Nevell (1997), p. 100.

- ↑ "Tram Times". Metrolink. Retrieved on 6 May 2007.

- ↑ "Rail map for Liverpool and Manchester" (PDF). National Rail. Retrieved on 6 May 2007.

- ↑ Wilson, James (26 April 2007). "A busy hub of connectivity", Financial Times – FT report – doing business in Manchester and the NorthWest, The Financial Times Limited.

- ↑ Sandra M Winhoven & Neil K Gibbs. "James Prescott Joule (1818 - 1889): A Manchester Son And The Father Of The International Unit Of Energy" (PDF). University of Manchester. Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ Saeger (1995), pp. 393–415

- ↑ "Novelist Tinniswood dies". BBC (9 January 2003). Retrieved on 25 April 2007.

- ↑ "Times Obituary of Baron Orme". The Times Online (28 April 2005). Retrieved on 25 April 2007.

- ↑ "David Gray: From music to marsh harriers". BBC Online (6 June 2008). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ Pierre Perrone (2 February 2003). "How We Met: Mark Radcliffe and Marc 'Lard' Riley". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved on 28 April 2007.

- ↑ Mike Rowbottom (7 August 2006). "An email conversation with Darren Campbell: 'Athletics mattered to me almost more than life itself'". The Independent. Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "About Darren Campbell". Nuff Respect Sport Managements Agency Online (2007). Retrieved on 25 April 2007.

- ↑ "Modahl gives BAF ultimatum". BBC Online (24 August 1998). Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "Cyril Washbrook player profile". Cricinfo. Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

Bibliography

- Hartwell, Clare; Matthew Hyde and Nikolaus Pevsner (2004). Lancashire : Manchester and the South-East. The buildings of England. New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10583-5.

- Kenyon, D (1989). "Notes on Lancashire Place-Names 2, The Later Names". The English Place-Name Society Journal 21: 23–53.

- Nevell, Mike (1992). Tameside Before 1066. Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 1-871324-07-6.

- Nevell, Mike (1997). The Archaeology of Trafford. Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 1-870695-25-9.

- Nevell, Mike (2008). Manchester: The Hidden History. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4704-9.

- Richards, Raymond (1947). Old Cheshire Churches. London: Batsford.

- Saeger, James Schofield (January 1995). "The Mission and Historical Missions: Film and the Writing of History". The Americas (Academy of American Franciscan History) 51 (3): 393–415. doi:.

- Swain, Norman (1987). A History of Sale from earliest times to the present day. Wilmslow: Sigma Press. ISBN 1-85058-086-3.

- Youngs, F. A. (1991). "Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Vol. II: Northern England". The English Historical Review (Oxford University Press) 2.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||