Saints Cyril and Methodius

| Saints Cyril and Methodius | |

|---|---|

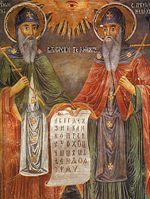

"Saints Cyril and Methodius holding Cyrillic alphabet," a mural by Bulgarian icon-painter Z. Zograf, 1848, Troyan Monastery |

|

| Bishops and Confessors; Equals to the Apostles; Patrons of Europe; Apostles to the Slavs | |

| Born | 827 and 826, Thessaloniki, Byzantine Empire (present-day Greece) |

| Died | February 14, 869 and 6 April 885 |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion Lutheran Church |

| Feast | February 14 (present Roman Catholic calendar); July 5 (Roman Catholic calendar 1880-1886); July 7 (Roman Catholic calendar 1887-1969) May 11(May 24) (Eastern Orthodox Church) July 5 (Czech Republic and Slovakia) |

| Attributes | brothers depicted together; Eastern bishops holding up a church; Eastern bishops holding an icon of the Last Judgment[1] Often, Cyril is depicted wearing a monastic habit and Methodius vested as a bishop with omophorion. |

| Patronage | Bulgaria, Czech Republic (including Bohemia, and Moravia), Ecumenism, unity of the Eastern and Western Churches, Europe, Slovakia[1] |

Saints Cyril and Methodius (Greek: Κύριλλος και Μεθόδιος, Old Church Slavonic: Кѷриллъ и Меѳодїи [2]) were two Byzantine Greek[3] brothers born in Thessaloniki in the 9th century, who became missionaries of Christianity among the Slavs of Great Moravia and Pannonia. Through their work they influenced the cultural development of all Slavic peoples for which they received the title "Apostles to the Slavs." They are credited with devising the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet used to transcribe the Old Church Slavonic language. The Cyrillic alphabet, which was based on the Glagolitic alphabet, is used in a number of Slavic and other languages. After their death, their pupils continued their missionary work among other Slavic peoples. Both brothers are venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as saints with the title of "Equals to the Apostles." In 1880, Pope Leo XIII introduced their feast into the calendar of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1980, Pope John Paul II declared them Co-patrons of Europe, together with Saint Benedict of Nursia.[4]

Contents |

Early career

Early life

The two brothers, Cyril and Methodius were born in Thessaloniki in 827 and 826 respectively to a Byzantine Greek "drungarios" (a military rank) named Leon. Cyril was reputedly the youngest of seven brothers, according to the "Vita Cyrilli" ("The Life of Cyril"). Cyril's birth name was Constantine (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Konstantínos) and he was probably renamed Cyril (Greek for 'Lordly') just before or after his death in Rome.

The two brothers lost their father when Cyril was only fourteen, and their uncle Theoktistos (Greek: Θεόκτιστος) became their protector. Theoktistos was a "Logothetes tou dromou," a powerful Byzantine official, responsible for the postal services and the diplomatic relations of the Empire. He was also responsible, along with the regent Bardas, for initiating a far-reaching educational program within the Empire which culminated in the establishment of the University of Magnaura, where Cyril was to teach. Theoktistos invited (843) Cyril to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and helped him continue his studies at the University there. He also arranged the later placement of Methodius (Greek: Μεθόδιος Methódios) as an abbot in the famous Greek monastery of Polychron (Μονή Πολυχρονίου) in Constantinople.[5]

Photius is said to have been among Cyril’s teachers; Anastasius Bibliothecarius mentions their later friendship, as well as a conflict between them on a point of doctrine. Cyril learned an eclectic variety of knowledge including astronomy, geometry, rhetoric and music. However, it was in the field of linguistics that Cyril particularly excelled. Besides his native Greek language, he was fluent in Latin, Arabic, Hebrew; and Slavonic.

After the completion of his education Cyril took holy orders and became a monk. He seems to have held the important position of "chartophylax," or secretary to the patriarch and keeper of the archives, with some judicial functions also. After six months' quiet retirement in a monastery he began to teach philosophy and theology.

Early missions

The fact that Cyril was a master theologian with a good command of both the Arabic and Hebrew languages made him eligible for his first state mission to the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutawakkil in order to discuss the principle of the Holy Trinity with the Arab theologian and to tighten the diplomatic relations between the Abbashid Caliphate and the Empire.

Cyril also took an active role in relations with the other two great Judaic, monotheistic religions, Islam and Judaism. He penned fiercely anti-Jewish polemics, perhaps connected with his mission to the Khazar Khaganate, a state located near the Sea of Azov ruled by a Jewish king who allowed Jews, Muslims, and Christians to live peaceably side by side. He also undertook a mission to the Arabs with whom, according to the "Vita", he held discussions. He is said to have learned the Hebrew, Samaritan and Arabic languages during this period.

The second mission (860) requested by the Byzantine Emperor Michael III and the Patriarch of Constantinople Photius (a professor of Cyril's at the University and his guiding light in earlier years) was a missionary expedition to the Khazar Khagan in order to prevent the expansion of Judaism there. This mission was unsuccessful, as later the Khagan imposed Judaism to his people as the national religion. It has been claimed that Methodius also accompanied Cyril on the mission to the Khazars, but this is probably a later invention. The account of his life presented in the Latin "Legenda" claims that he also learned the Khazar language while in Chersonesos, in Taurica (today Crimea).

After his return to Constantinople, Cyril assumed the role of professor of philosophy at the University while his brother had by this time become a significant player in Byzantine political and administrative affairs, and an abbot of his monastery.

Mission to the Slavs

Great Moravia

In 862, both brothers were to enter upon the work which gives them their historical importance. That year the Prince Rastislav of Great Moravia requested that the Emperor Michael III and the Patriarch Photius send missionaries to evangelize his Slavic subjects. His motives in doing so were probably more political than religious. Rastislav had become king with the support of the Frankish ruler Louis the German, but subsequently sought to assert his independence from the Franks. He is said to have expelled missionaries of the Roman Church and instead turned to Constantinople for ecclesiastical assistance and, presumably, a degree of political support.[5] The request provided a convenient opportunity to expand Byzantine influence, and the task was entrusted to Cyril and Methodius. Their first work seems to have been the training of assistants. In 863, they began the task of translating the Bible into the language now known as Old Church Slavonic and travelled to Great Moravia to promote it. They enjoyed considerable success in this endeavour. However, they came into conflict with German ecclesiastics who opposed their efforts to create a specifically Slavic liturgy.

For the purpose of this mission, they devised the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet to be used for Slavonic manuscripts. The Glagolitic alphabet was suited to match the specific features of the Slavic language and its descendant alphabet, the Cyrillic Alphabet, is still used by many languages today.[5]

They also translated Christian texts for Slavs into the language that is now called Old Church Slavonic and wrote the first Slavic Civil Code, which was used in Great Moravia. The language derived from Old Church Slavonic, known as Church Slavonic, is still used in liturgy by several Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches.

It is impossible to determine with certainty what portions of the Bible the brothers translated. The New Testament and the Psalms seem to have been the first, followed by other lessons from the Old Testament. The "Translatio" speaks only of a version of the Gospels by Cyril, and the "Vita Methodii" only of the "evangelium Slovenicum," though other liturgical selections may also have been translated.

Nor is it known for sure which liturgy, that of Rome or that of Constantinople, they took as a source. They may well have used the Roman alphabet, as suggested by liturgical fragments which adhere closely to the Latin type. This view is confirmed by the "Prague Fragments" and by certain Old Glagolitic liturgical fragments brought from Jerusalem to Kiev and there discovered by Saresnewsky-- probably the oldest document for the Slavonic tongue; these adhere closely to the Latin type, as is shown by the words "Mass," "Preface," and the name of one Felicitas. In any case, the circumstances were such that the brothers could hope for no permanent success without obtaining the authorization of Rome.

Journey to Rome

In 867, Pope Nicholas I invited the brothers to Rome. Their evangelizing mission in Moravia had by this time become the focus of a dispute with Theotmar, the Archbishop of Salzburg and bishop of Passau, who claimed ecclesiastical control of the same territory and wished to see it use the Latin liturgy exclusively. Travelling with the relics of Saint Clement and a retinue of disciples, and passing through Pannonia (the Balaton Principality), where they were well received by Prince Koceľ (Kocelj, Kozel), they finally arrived in Rome in 868 where they were warmly received. This was partly due to their bringing with them the relics of Saint Clement; while the rivalry with Constantinople, as to the jurisdiction over the territory of the Slavs would incline Rome to value the brothers and their influence.[5]

The brothers were praised for their learning and cultivated for their influence in Constantinople. Anastasius would later call Cyril "the teacher of the Apostolic See." Their project in Moravia found support from Pope Adrian II, who formally authorized the use of the new Slavic liturgy. The ordination of the brothers' Slav disciples was performed by Formosus and Gauderic, two prominent bishops, and the newly made priests officiated in their own tongue at the altars of some of the principal churches. Feeling his end approaching, Cyril put on the monastic habit and died fifty days later (February 14, 869). There is practically no basis for the assertion of the Translatio (ix.) that he was made a bishop; and the name of Cyril seems to have been given to him only after his death.

Methodius alone

Methodius now continued the work among the Slavs alone; not at first in Great Moravia, but in Pannonia (in the Balaton Principality), owing to the political circumstances of the former country, where Rastislav had been taken captive by his nephew Svatopluk, then delivered over to Carloman, and condemned in a diet of the empire at the end of 870.

Friendly relations, on the other hand, had been established with Koceľ on the journey to Rome. This activity in Pannonia, however, made a conflict inevitable with the German episcopate, and especially with the bishop of Salzburg, to whose jurisdiction Pannonia had belonged for seventy-five years. In 865 Bishop Adalwin is found exercising all Episcopal rights there, and the administration under him was in the hands of the archpriest Riehbald. The latter was obliged to retire to Salzburg, but his superior was naturally disinclined to abandon his claims. Methodius sought support from Rome; the Vita asserts that Koceľ sent him thither with an honorable escort to receive Episcopal consecration.

The letter given as Adrian's in chap. viii., with its approval of the Slavonic mass, is a pure invention. It is noteworthy that the pope named Methodius not bishop of Pannonia, but archbishop of Sirmium, thus superseding the claims of Salzburg by an older title. The statement of the "Vita" that Methodius was made bishop in 870 and not raised to the dignity of an archbishop until 873 is contradicted by the brief of Pope John VIII, written in June, 879, according to which Adrian consecrated him archbishop; John includes in his jurisdiction not only Great Moravia and Pannonia, but Serbia as well.

Methodius’ final years

The archiepiscopal claims of Methodius were considered such an injury to the rights of Salzburg that he was forced to answer for them at a synod held at Regensburg in the presence of King Louis. The assembly, after a heated discussion, declared the deposition of the intruder, and ordered him to be sent to Germany, where he was kept a prisoner for two and a half years. In spite of the strong representations of the "Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum," written in 871 to influence the pope, though not avowing this purpose, Rome declared emphatically for Methodius, and sent a bishop, Paul of Ancons, to reinstate him and punish his enemies, after which both parties were commanded to appear in Rome with the legate.

The papal will prevailed, and Methodius secured his freedom and his archiepiscopal authority over both Great Moravia and Pannonia, though the use of Slavonic for the mass was still denied to him. His authority was restricted in Pannonia when after Koceľ's death the principality was administered by German nobles; but Svatopluk now ruled with practical independence in Great Moravia, and expelled the German clergy. This apparently secured an undisturbed field of operation for Methodius; and the Vita (x.) depicts the next few years (873–879) as a period of fruitful progress. Methodius seems to have disregarded, wholly or in part, the prohibition of the Slavonic liturgy; and when Frankish clerics again found their way into the country, and the archbishop's strictness had displeased the licentious Svatopluk, this was made a cause of complaint against him at Rome, coupled with charges regarding the Filioque.

Methodius vindicated his orthodoxy at Rome, the more easily as the creed was still recited there without the Filioque, and promised to obey in regard to the liturgy. The other party was conciliated by giving him a Swabian, Wiching, as his coadjutor. When relations were strained between the two, John VIII steadfastly supported Methodius; but after his death (December 882) the archbishop's position became insecure, and his need of support induced Goetz to accept the statement of the Vita (xiii.) that he went to visit the Eastern emperor.

It was not, however, until after Methodius' death, which is placed, though not with certainty, on 8 April, 885, that the animosity erupted into an open conflict. Gorazd, whom Methodius had designated as his successor, was not recognised by Pope Stephen V. The same Pope forbade the use of the Slavic liturgy and placed the infamous Wiching as Methodius' successor. The later exiled the disciples of the two brothers from Great Moravia in 885. They fled to the First Bulgarian Empire, where they were welcomed and commissioned to establish theological schools. There they devised the Cyrillic Alphabet on the basis of the Glagolitic Alphabet. Cyrillic gradually replaced Glagolitic as the alphabet of the Old Church Slavonic (Old Bulgarian) language, which became the official language of the Bulgarian Empire and later spread to the Eastern Slav lands of Kievan Rus'. Cyrillic eventually spread throughout most of the Slavic world to become the standard alphabet in the Orthodox Slavic countries. Hence, Cyril and Methodius' efforts also paved the way for the spread of Christianity throughout Eastern Europe.

Invention of the Glagolitic

The Glagolitic alphabet or Glagolitsa, based primarily on the Greek uncial writing of the 9th century, is the oldest known Slavic alphabet and was created by the two brothers, in order to translate the Bible and other texts into the Slavic languages. The alphabet was then used in Great Moravia between 863 (with the arrival of Cyril and Methodius) and 885 (with the expulsion of their students) for government and religious documents and books, and at the Great Moravian Academy (Veľkomoravské učilište) founded by Cyril, where followers of Cyril and Methodius were educated, by Methodius himself among others. The alphabet has been traditionally attributed to Cyril. That fact has been confirmed explicitly by the papal letter Industriae tuae (880) approving the use of Old Church Slavonic, which says that the alphabet was "invented by Constantine the Philosopher". The term invention need not exclude the possibility of the brothers having made use of earlier letters, but implies only that before that time the Slavic languages had no distinct script of their own.

The early Cyrillic alphabet was a simplification of the Glagolitic alphabet which more closely resembled the Greek alphabet. It has been attributed to Saint Clement of Ohrid, a disciple of Saints Cyril and Methodius. However, recent studies have suggested that the Cyrillic alphabet was more likely developed at the Preslav Literary School in northeastern Bulgaria in the early 10th century and was named so in honour of St. Cyril.

Slavic origin hypothesis

A popular opinion among Slavic nations holds that Cyril and Methodius were themselves of Slavic background. Theories and positions of authors who have maintained such views range from Greek father and Bulgarian mother[6] to purely Slavonic (or, more specifically, Bulgarian) origin. "It is a long lasting dispute: what was the ethnicity of Constantine-Cyril and Methodius—Greek or Bulgarian?"[7].

- The "Bulgarian" (or, in a wider form, "Slavonic") version is probably the first explicitly documented one. It is based primarily on the evidence of the short variant of St. Cyril's biography (so-called "Успение Кириллово" (Uspenie Kirillovo) - "Assumption of St. Cyril"), an Old Slavonic text saying that St. Cyril "родомъ сыи блъгаринь" (rodomŭ syi blŭgarinĭ, "being Bulgarian by birth"). Two copies of the text (one belongs to the beginning of the 15th century, another from late 15th - early 16th century) are published in: Боню Ст. Ангелов (Boniu St. Angelov), Из старата българска, руска и сръбска литература (From old Bulgarian, Russian and Serbian literature), Sofia, 1978, pp. 7-10 and 13-16. This version is popular mostly among Bulgarian scholars. Critics say that "Assumption of St. Cyril" is not a very reliable source: it is a relatively late evidence, and it contains a lot of other dubious statements. [8]

- The mixed origin version stipulates that the brothers were born to a Greek father and a Slavic mother. One argument for this version (and/or Slavonic origin version as well), the following evidence from the earliest and most detailed Cyrilo-Methodian source—"Life of St. Cyril": "as a suckling, he did not accept the foster-mother, and only the milk of his own mother could feed him". As a symbolic presage of his further life—service for the Slavonic people—it can be interpreted as service to the people of his mother (see: Dinekov and Likhachyov, ibid.).

- One more point of view is popular in Slavonic literature and is shared by Florya himself: "при имеющемся состоянии источников вопрос об этническом происхождении Кирилла и Мефодия определенно решен быть не может" (under existing state of the primary sources, the question about the ethnic origin of Cyril and Methodius cannot be solved determinately—Florya, op. cit., p. 205). Or: "станем поэтому в вопросе о национальности Кирилла и Мефодия на более мудрые позиции и признаем их славянами по языку и самосознанию, не заглядывая в вопрос об их крови — славянской, греческой или иной" (therefore, let us stand in the problem of Cyril and Methodius ethnicity on a wiser position: let us confess them Slavs in language and in self-consciousness, not looking into the question of their blood—Slavonic, Greek, or other—Dinekov and Likhachyov, op. cit., p. 9).

Commemoration

Saints Cyril and Methodius Day

The Canonization process much more relaxed in the decades follwing Cyril's death than today, Cyril was regarded by his disciples as a saint following his death. His cult spread among the nations he evangelized and subsequently to the wider Christian Church, resulting is the reknown of his holiness, along with that of his brother Methodius. Indeed, there were calls for Cyril's canonization by the crowds lining the Roman streets during his funeral procession. Their first apearance in a papal document is Grande Munus by Leo XIII in 1880. The two brothers are known as the "Apostles of the Slavs" and are still highly regarded by both Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians. Sts Cyril and Methodius' feast day is currently celebrated on February 14 in the Roman Catholic Church (to coincide with the date of St Cyril's death); on May 11 in the Eastern Orthodox Church (though note that for Eastern Orthodox Churches still on the Julian Calendar or 'old calendar' this is May 24 according to the Gregorian calendar); and on July 7 according to the old sanctoral calendar that existed before the revisions of the Second Vatican Council. The two brothers were declared "Patrons of Europe" in 1980 (see Egregiae Virtutis). St. Cyril Peak on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named for Cyril.

"Saints Cyril and Methodius Day" is a holiday, usually celebrated on May 11 (May 24) in countries which observe Eastern Orthodox tradition, and on July 5 in countries that observe Roman Catholic tradition. It commemorates the creation of the Slavic Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets by the brothers Saints Cyril and Methodius. There is evidence that the Cyrillic alphabet was not created by Cyril and Methodius but by their pupil, Clement of Ohrid, but the alphabet bears Cyril's name nonetheless, and the evidence is still not enough to disprove that.) The celebration also commemorates the introduction of literacy and the preaching of the gospels in the Slavonic language by the brothers.

According to old Bulgarian chronicles, the day of the holy brothers used to be celebrated ecclesiastically as early as XI Century. The first recorded secular celebration of the Saints Cyril and Methodius Day as the "Day of the Bulgarian script", as it is traditionally accepted by Bulgarian science, was held in the town of Plovdiv on May 11, 1851, when a local Bulgarian school was named "Saints Cyril and Methodius," both acts on initiative of the prominent Bulgarian enlightener Naiden Gerov,[9] although an Armenian traveller mentioned his visit at "celebration of the Bulgarian script" in the town of Shumen on May 22, 1803.[10]

Nowadays, the day is celebrated as a public holiday in the following countries:

- In Bulgaria it is celebrated on May 24 and is known as the "Bulgarian Education and Culture, and Slavonic Literature Day" (Bulgarian: Ден на българската просвета и култура и на славянската писменост), a national holiday celebrating Bulgarian culture and literature as well as the alphabet. It is also known as "Alphabet, Culture, and Education Day" (Bulgarian: Ден на азбуката, културата и просвещението).

- In the Republic of Macedonia, it is celebrated on May 24 and is known as the "Saints Cyril and Methodius, Slavonic Enlighteners' Day" (Macedonian: Св. Кирил и Методиј, Ден на сесловенските просветители), a national holiday. Macedonian Government took the decision for the statute of national holiday in October 2006 and Macedonian Parliament passed a corresponding law in the beginning of 2007.[11] Before that it was celebrated only in the schools. It is also known as the day of the "Solun Brothers" (Macedonian: Солунските браќа).

- In the Czech Republic it is celebrated on July 5 as "Slavic Missionaries Cyril and Methodius Day" (Czech: Den slovanských věrozvěstů Cyrila a Metoděje).

- In Russia, it is celebrated on May 24 and is known as the "Slavonic Literature and Culture Day" (Russian: День славянской письменности и культуры), celebrating Slavonic culture and literature as well as the alphabet. Its celebration is ecclesiastical (May 11 on the Church's Julian calendar), and it is not a public holiday in Russia.

- In Slovakia it is celebrated on July 5 as "St. Cyril and Metod Day." (Slovak: Sviatok svätého Cyrila a Metoda)

The saints' feast day is celebrated by the Eastern Orthodox Church on May 11 and by the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion on February 14 as "Saints Cyril and Methodius Day." The Lutheran Churches commemorate the two saints either on February 14 or May 11. It is a public holiday in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, the Republic of Macedonia, and Slovakia; it is celebrated in Russia as a holiday associated with the two brothers, who are considered patrons of learning and education.

In the Czech lands and Slovakia, the two brothers were originally commemorated on March 9, but Pope Pius IX changed this date to July 5. Today, "Sts Cyril and Methodius Day," believed to be the date of the arrival of the two brothers to Great Moravia in 863, is a national holiday in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Other commemoration

Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje in Republic of Macedonia, St. Cyril and St. Methodius University of Veliko Tarnovo in Bulgaria and in Trnava, Slovakia bear the name of the two saints. In the United States, SS. Cyril and Methodius Seminary in Orchard Lake, Michigan, bears their name.

St. Cyril Peak and St. Methodius Peak on Livingston Island in the Tangra Mountains, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica are named for the two brothers.

Saint Cyril's remains are interred in a shrine-chapel within the Basilica di San Clemente in Rome, Italy. The chapel holds a Madonna by Sassoferrato.

The Basilica of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Danville, Pennsylvania (the only Roman Catholic basilica dedicated to Ss. Cyril & Methodius in the world) is the Motherhouse chapel of the Sisters of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, a Roman Catholic women's religious community of pontifical rite dedicated to apostolic works of ecumenism, education, evangelization, and elder care.

See also

- Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Byzantine Empire

- Glagolitic alphabet

- SS. Cyril and Methodius Seminary

- St. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje

- SS. Cyril and Methodius National Library in Sofia

- St. Cyril and Methodius University of Veliko Tarnovo

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jones, Terry. "Methodius". Patron Saints Index. Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ New Church Slavonic: Кѷрі́ллъ и҆ Меѳо́дїй (Kỳrill” i Methodij)Bulgarian: Кирил и Методий. In later national Cyrillic Slavonic alphabets:

- Belarusian: Кірыла і Мяфодзій (Kiryła i Miafodzij)

- Bulgarian: Кирил и Методий (Kiril i Metodij)

- Macedonian: Кирил и Методиј (Kiril i Metodij)

- Russian: Кирилл и Мефодий (Kirill i Mefodij), pre-1918 spelling: Кириллъ и Меѳодій (Kirill” i Methodij)

- Serbian: Ћирило и Методије (Ćirilo i Metodije)

- Ukrainian: Кирило і Мефодій (Kyrylo i Mefodij)

- ↑ Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05, s.v. "Cyril and Methodius, Saints"; Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica Incorporated, Warren E. Preece - 1972, p.846, s.v., "Cyril and Methodius, Saints" and "Eastern Orthodoxy, Missions ancient and modern"; Encyclopedia of World Cultures, David H. Levinson, 1991, p.239, s.v., "Social Science"; Eric M. Meyers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, p.151, 1997; Lunt, Slavic Review, June, 1964, p. 216; Roman Jakobson, Crucial problems of Cyrillo-Methodian Studies; Leonid Ivan Strakhovsky, A Handbook of Slavic Studies, p.98; V.Bogdanovich , History of the ancient Serbian literature, Belgrade, 1980, p.119

- ↑ Egregiae Virtutis, apostolic letter of Pope John Paul II, December 31, 1980 (Latin)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Encyclopedia Britannica, Cyril and Methodius, Saints, O.Ed., 2008

- ↑ Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801439779.

- ↑ П. Н. Динеков, Д. С. Лихачёв (P. N. Dinekov, D. S. Likhachyov), Дело Константина-Кирилла Философа и его брата Мефодия (The work of Constantine-Cyril the Philosopher and his brother Methodius), in: Жития Кирилла и Мефодия. Факсимильное издание (Lives of Cyril and Methodius. Fac-simile edition), Moscow-Sofia, 1986, p. 8.

- ↑ Б. Н. Флоря (B. N. Florya), Сказания о начале славянской письменности (Narrations on the beginning of Slavonic written language), 2nd ed., St. Petersburg, 2000 (ISBN 5-89329-328-2), p. 203-204

- ↑ "История на България", Том 6 Българско Възраждане 1856-1878, Издателство на Българската академия на науките, София, 1987, стр. 106 (in Bulgarian; in English: "History of Bulgaria", Volume 6 Bulgarian Revival 1856-1878, Publishing house of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, 1987, page 106).

- ↑ Jubilee speech of the Academician Ivan Yuhnovski, Head of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, held on May 23, 2003, published in Information Bulletin of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 3(62), Sofia, 27 June 2003 (in Bulgarian).

- ↑ Announcement about the eleventh session of the Macedonian Government on October 24, 2006 from the official site of the Macedonian Government (in Macedonian).

References

- This article includes content derived from the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1914, which is in the public domain.

External links

- Slavorum Apostoli by Pope John Paul II

- Cyril and Methodius - Encyclical letter, December 31, 1980 by Pope John Paul II

- "Cyril and Methodius, Saints" article in Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, Cyril and Methodius, Saints.

- 24 May - is the Day of Cyrillic Alphabet and St. Cyril and St. Methody

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Sts. Cyril and Methodius

- "Equal to Apostles SS. Cyril and Methodius Teachers of Slavs", by Prof. Nicolai D. Talberg

- Catholic Culture

- Cyril and Methodius at orthodoxwiki

- Bulgarian Official Holidays, National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria: in English, in Bulgarian

- Bank holidays in the Czech Republic, Czech National Bank: in English, in Czech

- "Landmarks of Culture", Russian Federation Agency of Culture and Cinematography, in Russian

- US embassy in Bratislava's Embassy Holidays for 2006;

- British embassy in Bratislava's Embassy Holidays for 2006

- 24 May - The Day Of Slavonic Alphabet, Bulgarian Enlightenment and Culture [1]

- 1140 Years of Slavonic Script, Information Bulletin of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 3(62), Sofia, 27 June 2003 (in Bulgarian)

- Cyril at Patron Saints Index

- Saint Cyril in Orthodoxy

- Contemporary sources

- Lettera Apostolica

- Epistola Enciclica

- Sources on St Cyril and Methodios' Ethnicity