Confession

The confession of one's sins is a religious practice important to many faiths, e.g., Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Contents |

Christianity

In the Christian faith and practice (James 5:16), confession is similar to the criminal one—to admit one's guilt. Confession of one's sins, or at least of one's sinfulness, is seen by most churches as a pre-requisite for becoming a Christian.

Confession of sins

Roman Catholicism

In Roman Catholic teaching, the sacrament of Penance (commonly called confession but more recently referred to as Reconciliation, or more fully the Sacrament of Reconciliation) is the method used by the Church by which individual men and women may confess sins committed after baptism and have them absolved by a priest. This sacrament is known by many names, including penance, reconciliation and confession (Catechism of the Catholic Church, Sections 1423-1442). While official Church publications always refer to the sacrament as "Penance", "Reconciliation" or "Penance and Reconciliation", many laypeople continue to use the term "confession" in reference to the sacrament. Roman Catholics believe that priests have been given the authority by Jesus and God to exercise the forgiveness of sins here on earth.

The basic form of confession has not changed for centuries, although at one time confessions were made publicly.[1] In theological terms, the priest acts in persona Christi and receives from the Church the power of jurisdiction over the penitent. Typically the penitent begins the confession by saying, "Bless me Father, for I have sinned. It has been [time period] since my last confession." The penitent then must confess mortal sins in order to restore his/her connection to God's grace and not to merit Hell. The sinner may also confess venial sins; this is especially recommended if the penitent has no mortal sins to confess. The intent of this sacrament is to provide healing for the soul as well as to regain the grace of God, lost by sin. The Council of Trent (Session Fourteen, Chapter I) quoted John 20:22-23 as the primary Scriptural proof for the doctrine concerning this sacrament, but Catholics also consider Matthew 9:2-8, 1 Corinthians 11:27, and Matthew 16:17-20 to be among the Scriptural bases for the sacrament.

Absolution in the Roman rite takes this form (with the essential words in bold):

God the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son, has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins; through the ministry of the Church may God give you pardon and peace, and I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Before the Second Vatican Council, and still practiced in traditionalist parishes, the priest would always absolve the penitent in Latin, using the following words, followed by an additional prayer.

Absolution (with the essential words in bold), and post-absolution prayer:

Dominus noster Jesus Christus te absolvat; et ego auctoritate ipsius te absolvo ab omni vinculo excommunicationis (suspensionis) et interdicti in quantum possum et tu indiges. [making the Sign of the Cross:] Deinde, ego te absolvo a peccatis tuis in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Amen.

Passio Domini nostri Jesu Christi, merita Beatæ Mariæ Virginis et omnium sanctorum, quidquid boni feceris vel Mali sustinueris sint tibi in remissionem peccatorum, augmentum gratiæ et præmium vitæ æternæ.

Translation: "May our Lord Jesus Christ absolve you; and by His authority I absolve you from every bond of excommunication and interdict, so far as my power allows and your needs require. [making the Sign of the Cross:] Thereupon, I absolve you of your sins in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Amen."

"May the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the merits of the Blessed Virgin Mary and of all the saints obtain for you that whatever good you do or whatever evil you bear might merit for you the remission of your sins, the increase of grace and the reward of everlasting life."

The penitent must make an act of contrition, a prayer acknowledging his/her faults before God. It typically commences: O my God, I am heartily sorry... The reception of sacramental absolution is considered necessary before receiving the Eucharist if one has guilt for a mortal sin (and in fact, knowningly receiving the Eucharist under mortal sin is considered an additional mortal sin). The Roman Catholic Church teaches that the Sacrament of Penance is the only ordinary way in which a person can receive forgiveness for mortal sins committed after baptism. However, perfect contrition (a sorrow motivated by love of God rather than of fear of punishment) is an extraordinary way of removing the guilt of mortal sin before or without confession (if there is no opportunity of confessing to a priest). Such contrition would include the intention of confessing and receiving sacramental absolution. For the absolution to be valid, contrition must be had. Imperfect contrition (sorrow arising from a less pure motive, such as fear of Hell), is sufficient for a valid confession, but is not, by itself, sufficient to remove the guilt of sin.

A mortal sin must be about a serious matter, have been committed with full consent, and be known to be wrong. Other sins would be classed as venial; confession of venial sins is strongly recommended but not obligatory, and is said to strengthen the penitent against temptation to mortal sin. Serious matters for a mortal sin, according to Roman Catholic teaching, include for example: murder, blasphemy, and adultery. It is a dogmatic belief of the faith that if a person guilty of mortal sin dies without either receiving the sacrament or experiencing perfect contrition with the intention of confessing to a priest, he will receive eternal damnation.

In order for the sacrament to be valid the penitent must do more than simply confess his known mortal sins to a priest. He must a) be truly sorry for each of the mortal sins he committed, b) have a firm intention never to commit them again, and c) perform the penance imposed by the priest. Also, in addition to confessing the types of mortal sins committed, the penitent must disclose how many times each sin was committed, to the best of his ability.

In 1215, after the Fourth Council of the Lateran, the Code of Canon Law required all Roman Catholics to confess at least once a year, although frequent reception of the sacrament is recommended such as reception weekly or monthly. In reality many Roman Catholics confess far less or more than is required; of all practices of the faith it is perhaps among the most common to be neglected.

For Catholic priests, the confidentiality of all statements made by penitents during the course of confession is absolute. This strict confidentiality is known as the Seal of the Confessional. According to the Code of Canon Law, 983 §1, "The sacramental seal is inviolable; therefore it is absolutely forbidden for a confessor to betray in any way a penitent in words or in any manner and for any reason." The priest is bound to secrecy and cannot be excused either to save his own life or that of another, or to avert any public calamity. No law can compel him to divulge the sins confessed to him. This is unique to the Seal of the Confessional. The violation of the seal of confession would be a sacrilege, and the priest would be subject to excommunication. Many other forms of confidentiality, including in most states attorney-client privilege, allow ethical breaches of the confidence to save the life of another.) For a priest to break that confidentiality would lead to a latae sententiae (automatic) excommunication reserved to the Holy See (Code of Canon Law, 1388 §1). In a criminal matter, a priest may encourage the penitent to surrender to authorities. However, this is the extent of the leverage he wields; he may not directly or indirectly disclose the matter to civil authorities himself.

There are limited cases where portions of a confession may be revealed to others, but always with the penitent's permission and always without actually revealing the penitent's identity. This is the case, for example, with unusually serious offenses, as some excommunicable offenses are reserved to the bishop or even to the Holy See, and their permission to grant absolution would first have to be obtained.

Civil authorities in the United States are usually respectful of this confidentiality. However, several years ago an attorney in Portland, Oregon, secretly recorded a confession without the knowledge of the priest or the penitent involved. This led to official protests by then local Archbishop Francis George and the Vatican. The tape has since been sealed, and the Federal Court has since ruled that the taping was in violation of the 4th Amendment, and ordered an injunction against any further tapings.

Frequent confession

Frequent confession is a spiritual practice of going to the sacrament of penance often and regularly in order to grow in holiness.

This practice "was introduced into the Church by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit," according to Pius XII. Confession of everyday faults is "strongly recommended by the Church." (CCC 1458) Paul VI said that frequent confession is "of great value."

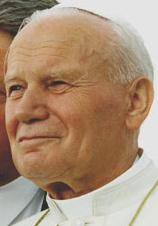

John Paul II who went to confession weekly, enumerated these advantages:

- we are renewed in fervor,

- strengthened in our resolutions, and

- supported by divine encouragement

Because of what he considered misinformation on this topic, he strongly recommended this practice and warned that those who discourage frequent confession "are lying."

Manuals of confession

In the Middle Ages manuals of confession constituted a literary genre. These manuals were guidebooks on how to obtain the maximum benefits from the sacrament. There were two kinds of manuals: those addressed to the faithful, so that they could prepare a good confession, and those addressed to the priests, who had to make sure that no sins were left unmentioned and the confession was as thorough as possible. The priest had to ask questions, being careful not to suggest sins that perhaps the faithful had not thought of and give them ideas. Manuals were written in Latin and in the vernacular. See Les manuels de confession en castillan dans l'Espagne médiévale (in French)[2] about manuals of confession in medieval Spain. Various guidebooks for confession also appear frequently in the Eastern Church.

Eastern Orthodoxy and Eastern Catholicism

Within the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches, it is understood that the Mystery of confession and repentance has more to do with the spiritual development of the individual and much less to do with purification. Sin is not seen as a stain on the soul, but rather a mistake that needs correction.

In general, the Orthodox Christian chooses an individual to trust as his or her spiritual guide. In most cases this is the parish priest, but may be a starets (Elder, a monastic who is well-known for his or her advancement in the spiritual life) or any individual, male or female, who has received permission from a bishop to hear confession. This person is often referred to as one's "spiritual father" or "spiritual mother". Once chosen, the individual turns to his spiritual guide for advice on his or her spiritual development, confessing sins, and asking advice. Orthodox Christians tend to confess only to this individual and the closeness created by this bond makes the spiritual guide the most qualified in dealing with the person, so much so that no one can override what a spiritual guide tells his or her charges. What is confessed to one's spiritual guide is protected by the same seal as would be any priest hearing a confession. While one does not have to be a priest to hear confession, only an ordained priest may pronounce the absolution.

Confession does not take place in a confessional, but normally in the main part of the church itself, usually before an analogion (lectern) set up near the iconostasion. On the analogion is placed a Gospel Book and a blessing cross. The confession often takes place before an icon of Jesus Christ (usually the Icon of Christ "Not Made by Hand"). Orthodox understand that the confession is not made to the priest, but to Christ, and the priest stands only as witness and guide. Before confessing, the penitent venerates the Gospel Book and cross, and places the thumb and first two fingers of his right hand on the feet of Christ as he is depicted on the cross. The confessor will often read an admonition warning the penitent to make a full confession, holding nothing back.

In cases of emergency, of course, confession may be heard anywhere. For this reason, especially in the Russian Orthodox Church, the pectoral cross that the priest wears at all times will often have the Icon of Christ "Not Made by Hands" inscribed on it.

In general practice, after one confesses to one's spiritual guide, the parish priest (who may or may not have heard the confession) covers the head of the person with his Epitrachelion (Stole) and reads the Prayer of Absolution, asking God to forgive the transgression of the individual (the specific prayer differs between Greek and Slavic use). It is not uncommon for a person to confesses his sins to his spiritual guide on a regular basis but only seek out the priest to read the prayer before receiving Holy Communion.

In the Eastern Churches, clergy often make their confession in the sanctuary. A bishop, priest, or deacon will confess at the Holy Table (Altar) where the Gospel Book and blessing cross are normally kept. He confesses in the same manner as a layman, except that when a priest hears a bishop's confession, the priest kneels.

Orthodox Christians should go to confession at least four times a year; often during one of the four fasting periods (Great Lent, Nativity Fast, Apostles' Fast and Dormition Fast). Many pastors encourage frequent confession and communion. In some of the monasteries on Mount Athos, the monks will confess their sins daily.

Orthodox Christians will also practice a form of general confession, referred to as the rite of "Mutual Forgiveness". The rite involves an exchange between the priest and the congregation (or, in monasteries, between the superior and the brotherhood). The priest will make a prostration before all and ask their forgiveness for sins committed in act, word, deed, and thought. Those present ask that God may forgive him, and then they in turn all prostrate themselves and ask the priest's forgiveness. The priest then pronounces a blessing. The rite of Mutual Forgiveness does not replace the Mystery of Confession and Absolution, but is for the purpose of maintaining Christian charity and a humble and contrite spirit. This general confession is practiced in monasteries at the first service on arising (the Midnight Office) and the last service before retiring to sleep (Compline). Old Believers will perform the rite regularly before the beginning of the Divine Liturgy. The best-known asking of mutual forgiveness occurs at Vespers on the Sunday of Forgiveness, and it is with this act that Great Lent begins.

Anglicanism

The Anglican sacrament of confession and absolution is usually a component part of corporate worship, particularly at services of the Holy Eucharist. The form involves an exhortation to repentance by the priest, a period of silent prayer during which believers may inwardly confess their sins, a form of general confession said together by all present, and the pronouncement of absolution by the priest, often accompanied by the sign of the cross.

Private or auricular confession is also practiced by Anglicans and is especially common among Anglo-Catholics. The venue for confessions is either in the traditional confessional, which is the common practice among Anglo-Catholics, or in a private meeting with the priest. This practice permits a period of counselling and suggestions of acts of penance. Following the confession of sins and the assignment of penance, the priest makes the pronouncement of absolution. The seal of the confessional, as with Roman Catholicism, is absolute and any confessor who divulges information revealed in confession is subject to deposition and removal from office.

Historically, the practice of auricular confession was originally a highly controversial one within Anglicanism when priests of the Oxford Movement in the nineteenth century began to hear confessions, but they responded to criticisms by pointing to the fact that such is explicitly sanctioned in The Order for the Visitation of the Sick in the Book of Common Prayer, which contains the following direction:

Here shall the sick person be moved to make a special Confession of his sins, if he feel his conscience troubled with any weighty matter. After which Confession, the Priest shall absolve him (if he humbly and heartily desire it)

Auricular confession within mainstream Anglicanism became accepted in the second half of the 20th century; the 1979 Book of Common Prayer for the Episcopal Church in the USA provides two forms for it in the section "The Reconciliation of a Penitent." Private confession is also envisaged by the Canon Law of the Church of England, which contains the following, intended to safeguard the Seal of the Confessional:

if any man confess his secret and hidden sins to the minister, for the unburdening of his conscience, and to receive spiritual consolation and ease of mind from him; we...do straitly charge and admonish him, that he do not at any time reveal and make known to any person whatsoever any crime or offence so committed to his trust and secrecy[3]

There is no requirement for private confession, but a common understanding that it may be desirable depending on individual circumstances. An Anglican aphorism regarding the practice is "All may; none must; some should".[4]

Protestantism

Protestant churches believe that no intermediary is necessary between the Christian and God in order to be absolved from sins. Protestants, however, confess their sins in private prayer before God, believing this suffices to gain God's pardon. However confession to another is often encouraged when a wrong has been done to a person as well as to God. Confession is then made to the person wronged, and is part of the reconciliation process. In cases where sin has resulted in the exclusion of a person from church membership due to unrepentance, public confession is often a pre-requisite to readmission. The sinner confesses to the church his or her repentance and is received back into fellowship. In neither case is there any required format to the confessions, except for the steps taken in Matthew 18:15-20.

Lutheranism

Lutheran churches practice "confession and absolution" with the emphasis on the absolution, which is God's word of forgiveness. Confession and absolution may be either private to the pastor, called the "confessor" with the person confessing known as the "penitent," or corporate with the assembled congregation making a general confession to the pastor in the Divine Service. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries private confession and absolution largely fell into disuse; and, even at the present time, it is generally only used when specifically requested by the penitent or suggested by the confessor.

In his 1529 catechisms, Martin Luther praised private confession (before a pastor or a fellow Christian) "for the sake of absolution," the forgiveness of sins bestowed in an audible, concrete way (see John 20:23; Matthew 16:19; 18:18). The Lutheran reformers held that a complete enumeration of sins is impossible (Augsburg Confession XI with reference to Psalm 19:12) and that one's confidence of forgiveness is not to be based on the sincerity of one's contrition nor on one's doing works of satisfaction imposed by the confessor. The medieval church held confession to be composed of three parts: contritio cordis ("contrition of the heart"), confessio oris ("confession of the mouth"), and satisfactio operis ("satisfaction of deeds"). The Lutheran reformers abolished the "satisfaction of deeds," holding that confession and absolution consist of only two parts (Large Catechism VI, 15): the confession of the penitent and the absolution spoken by the confessor. Faith or trust in Jesus' complete active and passive satisfaction is what receives the forgiveness and salvation won by him and imparted to the penitent by the word of absolution.

The Lutheran Church of Sweden emphasizes the teaching of the Book of Concord that "confession and absolution" is a sacrament (Apology of the Augsburg Confession XIII, 4): sacramental confession to a Lutheran priest is contained in the Swedish massbook.

Buddhism

In Buddhism, confessing one's faults to a superior is an important part of Buddhist practice. In the various sutras, followers of the Buddha confessed their wrongdoing to Buddha [1].

Islam

In Islam, confession, or declaration to be more precise, of faith is one of the five pillars of Islam (see Shahadah). The act of seeking forgiveness from God is called Istighfar.

Judaism

In Judaism, confession is an important part of attaining forgiveness for both sins against God and another man. However, confession of sins is made to God and not man (except in asking for forgiveness of the victim of the sin). In addition, confession in Judaism is done communally in plural. Unlike the Christian "I have sinned," Jews confess that "We have sinned."

References

- ↑ Hanna, E. (1911). The Sacrament of Penance. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved September 14, 2008 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11618c.htm

- ↑ Halsall, Paul (ed.), Internet Medieval Sourcebook, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/sbook.html, retrieved on 2007-07-11

- ↑ (Proviso to Canon 113 of the Code of 1603, retained in the Supplement to the present Code)

- ↑ Becker, Michael Confession: None must, All may, Some should

See also

- Augsburg Confession, the central document describing the religious convictions of the Lutheran reformation

- See Confessions for a list of books and albums of that title, most notably Confessions by St. Augustine of Hippo

- A Confession by Leo Tolstoy in which he describes his conversion to Christianity

- Westminster Confession of Faith

External links

- The Catholic Encyclopedia's entries on the sacrament of reconciliation & on the Burial place of a martyr

- Confession - Catholic Sacrament of Reconciliation - Penance Novus Ordo

- Anglicanism and Confession

- Lutheran view on Confession

- Sacraments of Repentance and Confession in the Coptic Orthodox Church

- Confession in the Russian Orthodox Church (photo)

- Confession Eastern Orthodox Church