Supreme Court of the United States

| Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

|

| Court Details | |

|---|---|

| Established in: | 1789 |

| Jurisdiction: | United States |

| Location: | Washington, D.C. |

| Composition method: | Presidential nomination with Senatorial confirmation |

| Authorized by: | U.S. Const. |

| Judge term length: | Life tenure |

| Number of positions: | 9 |

| Website: | Supreme Court of the United States |

|

Chief Justice

|

|

| Currently: | John G. Roberts |

| In position since: | September 28, 2005 |

| United States of America |

|---|

|

|

This article is part of the series on the |

| The Court |

|

Decisions · Procedure |

| Current membership |

|

Chief Justice Retired Associate Justice |

| All members |

|

List of all members All nominations Court demographics |

| Court functionaries |

|

Clerks · Reporter of Decisions |

|

Other countries · Law Portal |

| United States |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

|

Legislature

Presidency

Judiciary

Elections

Political Parties

Subdivisions

|

|

Other countries · Atlas |

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest judicial body in the United States, and leads the federal judiciary. It consists of the Chief Justice of the United States and eight Associate Justices, who are nominated by the President and confirmed with the "advice and consent" of the Senate. Once appointed, Justices effectively have life tenure, serving "during good Behaviour,"[1] which terminates only upon death, resignation, retirement, or conviction on impeachment.[2] The Court meets in Washington, D.C. in the United States Supreme Court building. The Supreme Court is primarily an appellate court, but has original jurisdiction in a small number of cases.[3]

Contents |

History

The history of the Supreme Court is frequently described in terms of the Chief Justices who have presided over it.

Initially, during the tenures of Chief Justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the Court lacked a home of its own and any real prestige.

That changed during the Marshall Court (1801–1836), which declared the Court to be the supreme arbiter of the Constitution (see Marbury v. Madison) and made a number of important rulings which gave shape and substance to the constitutional balance of power between the federal government (referred to at the time as the "general" government) and the states. In Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, the Court ruled that it had the power to correct interpretations of the federal Constitution made by state supreme courts. Both Marbury and Martin confirmed that the Supreme Court was the body entrusted with maintaining the consistent and orderly development of federal law.

The Marshall Court ended the practice of each judge issuing his opinion seriatim, a remnant of British tradition, and instead one majority opinion of the Court was issued. The Marshall Court also saw Congress impeach a sitting Justice, Samuel Chase, who was acquitted. This impeachment was one piece of the power struggle between the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists after the election of 1800 and the subsequent change in power. The failure to remove Chase is thought to signal the recognition by Congress of judicial independence.

The Taney Court (1836–1864) made a number of important rulings, such as Sheldon v. Sill, which held that while Congress may not limit the subjects the Supreme Court may hear, it may limit the jurisdiction of the lower federal courts to prevent them from hearing cases dealing with certain subjects. However, it is primarily remembered for its ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford, the case which may have helped precipitate the Civil War. In the years following the Civil War, the Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (1864–1910) interpreted the new Civil War amendments to the Constitution, and developed the doctrine of substantive due process (Lochner v. New York; Adair v. United States).

Under the White and Taft Courts (1910–1930), the substantive due process doctrine reached its first apogee (Adkins v. Children's Hospital), and the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment applied some provisions of the Bill of Rights to the states through the Incorporation doctrine.

During the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson Courts (1930–1953), the court gained its own accommodation and radically changed its interpretation of the Constitution in order to facilitate the New Deal (West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Wickard v. Filburn), giving an expansive reading to the powers of the Federal Government.

The Warren Court (1953–1969) made a number of alternately celebrated and controversial rulings expanding the application of the Constitution to civil liberties, leading a renaissance in substantive due process. It held that segregation in public schools is unconstitutional (Brown v. Board of Education); the Constitution protects a general right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut); public schools cannot have official prayer (Engel v. Vitale), or mandatory Bible readings (Abington School District v. Schempp); many guarantees of the Bill of Rights apply to the states (e.g., Mapp v. Ohio, Miranda v. Arizona); an equal protection clause is not contained in the Fifth Amendment (Bolling v. Sharpe); and that the Constitution grants the right of retaining a court appointed attorney for those too indigent to pay for one (Gideon v. Wainwright).

The Burger Court (1969–1986) ruled that abortion was a constitutional right (Roe v. Wade), reached controversial rulings on affirmative action (Regents of the University of California v. Bakke) and campaign finance regulation (Buckley v. Valeo), and held that the implementation of the death penalty in many states was unconstitutional (Furman v. Georgia), but that the death penalty itself was not unconstitutional (Gregg v. Georgia).[4]

The Rehnquist Court (1986–2005) will primarily be remembered for its revival of the concept of federalism, which included restrictions on Congressional power under both the Commerce Clause (United States v. Lopez, United States v. Morrison) and the fifth section of the Fourteenth Amendment (City of Boerne v. Flores), as well as the fortification of state sovereign immunity (Seminole Tribe v. Florida, Alden v. Maine). It will also be remembered for its 5 to 4 decision in Bush v. Gore which ended the electoral recount during the presidential election of 2000 and led to the presidency of George W. Bush. In addition, the Rehnquist court decriminalized homosexual sex (Lawrence v. Texas); narrowed the right of labor unions to picket (Lechmere Inc. v. NLRB); altered the Roe v. Wade framework for assessing abortion regulations (Planned Parenthood v. Casey); and gave sweeping meaning to ERISA pre-emption (Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., Egelhoff v. Egelhoff), thereby denying plaintiffs access to state courts with the consequence of limiting compensation for torts to very circumscribed remedies (Aetna Health Inc. v. Davila, CIGNA Healthcare of Texas Inc. v. Calad); and affirmed the power of Congress to extend the term of copyright (Eldred v. Ashcroft).

The Roberts Court (2005–present) began with the confirmation and swearing in of Chief Justice John G. Roberts on September 29, 2005, and is the currently presiding court. The Court under Chief Justice Roberts is perceived[5] as moving towards the conservative end of the spectrum. Some of the major rulings so far have been in the areas of abortion (Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood, Gonzales v. Carhart); anti-trust legislation (Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc.); the death penalty (Baze v. Rees, Kennedy v. Louisiana); the Fourth Amendment (Hudson v. Michigan); free speech of government employees and of high school students (Garcetti v. Ceballos, Morse v. Frederick); military detainees (Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, Boumediene v. Bush); school desegregation (Parents v. Seattle); voting rights (Crawford v. Marion County Election Board); and the Second Amendment (District of Columbia v. Heller).

Composition

Size of the Court

The United States Constitution does not specify the size of the Supreme Court; instead, Article III of the Constitution gives Congress the power to fix the number of Justices. Originally, the total number of Justices was set at six by the Judiciary Act of 1789. As the country grew geographically, Congress increased the number of Justices to correspond with the growing number of judicial circuits: the court was expanded to seven members in 1807, nine in 1837 and ten in 1863.

In 1866, at the behest of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act which provided that the next three Justices to retire would not be replaced; thus, the size of the Court would eventually reach seven by attrition. Consequently, one seat was removed in 1866 and a second in 1867. In the Circuit Judges Act of 1869, the number of Justices was again set at nine, where it has since remained.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to expand the Court in 1937; his plan would have allowed the President to appoint one new, additional justice for each justice who reached the age of 70 years 6 months but did not retire from the bench, until the Court reached a maximum size of fifteen justices. Ostensibly, the proposal was made to ease the burdens of the docket on the elderly judges, but the President's actual purpose was to add Justices who would favor his New Deal policies, which had been regularly ruled unconstitutional by the Court. This plan, referred to often as the "Court-packing Plan," failed in Congress. The Court, however, moved from its opposition to Roosevelt's New Deal programs, rendering the President's effort moot. In any case, Roosevelt's unprecedented tenure in the White House allowed him to appoint eight Justices total to the Supreme Court (second only to George Washington) and promote one Associate Justice to Chief Justice.[6]

Nomination

Article II of the Constitution gives the President power to nominate justices, who are then appointed "by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate." As a general rule, Presidents nominate individuals who broadly share their ideological views. In many cases, a Justice's decisions may be contrary to what the nominating President anticipated. A famous instance was Chief Justice Earl Warren; President Eisenhower expected him to be a conservative judge, but his decisions are arguably among the most liberal in the Court's history. Eisenhower later called the appointment "the biggest damn fool mistake I ever made."[7] Because the Constitution does not set forth any qualifications for service as a Justice, the President may nominate anyone to serve. However, that person must receive the confirmation of the Senate, meaning that a majority of that body must find that person to be a suitable candidate for a lifetime appointment on the nation's highest court.

Confirmation

In modern times, the confirmation process has attracted considerable attention from special-interest groups, many of which lobby senators to confirm or to reject a nominee, depending on whether the nominee's track record aligns with the group's views. The Senate Judiciary Committee conducts hearings, questioning nominees to determine their suitability. At the close of confirmation hearings, the Committee votes on whether the nomination should go to the full Senate with a positive, negative or neutral report.

The practice of the nominee being questioned in person by the Committee is relatively recent. The first nominee to testify before the Committee was Harlan Fiske Stone in 1925. Some western senators were concerned with his links to Wall Street and expressed their opposition when Stone was nominated. Stone proposed what was then the novelty of appearing before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions; his testimony helped secure a confirmation vote with very little opposition. The second nominee to appear before the Committee was Felix Frankfurter, who only addressed (at the Committee's request) what he considered to be slanderous allegations against him. The modern practice of the Committee questioning nominees on their judicial views began with the nomination of John Marshall Harlan II in 1955; the nomination came shortly after the Court handed down the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, and several Southern senators attempted to block Harlan's confirmation, hence the decision to testify.[8]

Once the committee reports out the nomination, the whole Senate considers it; a simple majority vote is required to confirm or to reject a nominee. Rejections are relatively uncommon; the Senate has explicitly rejected only twelve Supreme Court nominees in its history. The most recent rejection of a nominee by vote of the full Senate came in 1987, when the Senate refused to confirm Robert Bork.

Not everyone nominated by the President has received a floor vote in the Senate. Although Senate rules do not necessarily allow a negative vote in committee to block a Supreme Court nomination, a nominee may be filibustered once debate on the nomination has begun in the full Senate. A filibuster indefinitely prolongs the debate thereby preventing a final vote on the nominee. While senators may attempt to filibuster a Supreme Court nominee in an attempt to thwart confirmation, no nomination for Associate Justice has ever been filibustered. However, President Lyndon Johnson's nomination of sitting Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice was successfully filibustered in 1968.

It is also possible for the President to withdraw a nominee's name at any time before the actual confirmation vote occurs. This usually happens when the President feels that the nominee has little chance of being confirmed: most recently, President George W. Bush withdrew his nomination of Harriet Miers before committee hearings had begun, citing concerns about Senate requests during her confirmation process for access to internal Executive Branch documents resulting from her position as White House Counsel. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan withdrew the nomination of Douglas H. Ginsburg because of allegations of marijuana use.

Until 1981, the approval process of Justices was frequently quick. From the Truman through Nixon administrations, Justices were typically approved within one month. From the Reagan administration through the current administration of George W. Bush, however, the process has taken much longer. Some speculate this is because of the increasingly political role Justices are said to play.[9]

Recess appointments

When the Senate is in recess, the President may make a temporary appointment without the Senate's advice and consent. Such a recess appointee to the Supreme Court holds office only until the end of the next Senate session (at most, less than two years). To continue to serve thereafter and be compensated for his or her service, the nominee must be confirmed by the Senate. Of the two Chief Justices and six Associate Justices who have received recess appointments, only Chief Justice John Rutledge was not subsequently confirmed for a full term. No president since Dwight Eisenhower has made a recess appointment to the Supreme Court and the practice has become highly controversial even when applied to lower federal courts.

Tenure

The Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their Offices during good Behavior" (unless appointed during a Senate recess). The term "good behavior" is well understood to mean Justices may serve for the remainder of their lives, although they can voluntarily resign or retire. A Justice can also be removed by Congressional impeachment and conviction. However, only one Justice has ever been impeached by the House (Samuel Chase, in 1805) and he was acquitted in the Senate, making impeachment as a restraint on the court something of a paper tiger. Moves to impeach sitting justices have occurred more recently (for example, William O. Douglas was the subject of hearings twice, once in 1953 and again in 1970), but they have not ever reached a vote in the House.

Because Justices have indefinite tenure, it is impossible to predict when a vacancy will next occur. Sometimes vacancies arise in quick succession, as in the early 1970s when Lewis Powell and William H. Rehnquist were nominated to replace Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II, who retired within a week of each other. Sometimes a great length of time passes between nominations such as the eleven years between Stephen Breyer's nomination in 1994 and the departures of Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice O'Connor (by death and retirement, respectively) in 2005.

Despite the variability, all but four Presidents so far have been able to appoint at least one Justice. The exceptions are William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, Andrew Johnson, and Jimmy Carter. Harrison died a month after taking office, though his successor (John Tyler) made an appointment during that presidential term. Taylor likewise died early in his presidential term, though an appointment was made before the term ended by Millard Fillmore. Johnson was denied the opportunity to appoint a Justice by a contraction in the size of the Court (see Size of the Court above). Carter is the only President who completed the entirety of the time in office for which he was elected without making a nomination to the Court.

Current membership

Below is a table of current Supreme Court Justices. ("Conf. Vote" = Senate Confirmation Vote)

| Name | Born | Appt. by | Conf. vote | First day | Prior positions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

January 27, 1955 (age 54) in Buffalo, New York | G.W. Bush | 78-22 | September 29, 2005 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (2003–2005); Private practice (1993–2003); Professor, Georgetown University Law Center (1992–2005); Principal Deputy Solicitor General (1989–1993); Private practice (1986–1989); Associate Counsel to the President (1982–1986); Special Assistant to the Attorney General (1981–1982) |

John Paul Stevens |

April 20, 1920 (age 89) in Chicago, Illinois | Ford | 98-0 | December 19, 1975 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (1970–1975); Private practice (1948–1970); Lecturer, University of Chicago Law School (1950–1954); Lecturer, Northwestern University School of Law (1954–1958) |

|

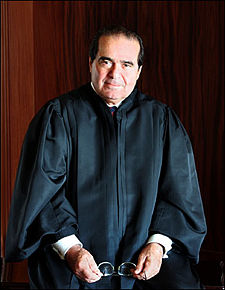

March 11, 1936 (age 73) in Trenton, New Jersey | Reagan | 98-0 | September 26, 1986 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (1982–1986); Professor, University of Chicago Law School (1977–1982); Assistant Attorney General (1974–1977); Professor, University of Virginia School of Law (1967–1974); Private practice (1961–1967) |

|

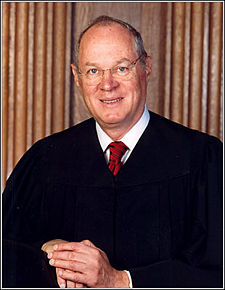

July 23, 1936 (age 73) in Sacramento, California | Reagan | 97-0 | February 18, 1988 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (1975–1988); Professor, McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific (1965–1988); Private practice (1963–1975) |

David Souter |

September 17, 1939 (age 70) in Melrose, Massachusetts | G.H.W. Bush | 90-9 | October 9, 1990 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (1990–1990); Associate Justice, New Hampshire Supreme Court (1983–1990); Associate Justice, New Hampshire Superior Court (1978–1983); Attorney General of New Hampshire (1976–1978); Deputy Attorney General of New Hampshire (1971–1976); Assistant Attorney General of New Hampshire (1968–1971); Private practice (1966–1968). |

|

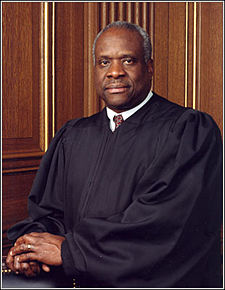

June 23, 1948 (age 61) in Pin Point, Georgia | G.H.W. Bush | 52-48 | October 23, 1991 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (1990–1991); Chairman, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1982–1990); Legislative Assistant for Missouri Senator John Danforth (1979–1981); employed by Monsanto Inc. (1977–1979); Assistant Attorney General of Missouri under State Attorney General John Danforth (1974–1977) |

Ruth Bader Ginsburg |

March 15, 1933 (age 76) in Brooklyn, New York | Clinton | 97-3 | August 10, 1993 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (1980–1993); General Counsel, American Civil Liberties Union (1973–1980); Professor, Columbia Law School (1972–1980); Professor, Rutgers University School of Law (1963–1972) |

|

August 15, 1938 (age 71) in San Francisco, California | Clinton | 87-9 | August 3, 1994 | Chief Judge, Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (1990–1994); Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (1980–1990); Professor, Harvard Law School (1967–1980) |

|

April 1, 1950 (age 59) in Trenton, New Jersey | G.W. Bush | 58-42 | January 31, 2006 | Circuit Judge, Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (1990–2006); Professor, Seton Hall University School of Law (1999–2004); U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey (1987–1990); Deputy Assistant Attorney General (1985–1987); Assistant to the Solicitor General (1981–1985); Assistant U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey (1977–1981) |

As of 2008, the average age of the U.S. Supreme Court justices is 68 years. See also Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Retired justices

Research suggests that justices sometimes strategically plan their decisions to leave the bench, with personal, institutional, and partisan factors playing a role.[10] The fear of mental decline and death often motivates justices to step down. The desire to maximize the Court's strength and legitimacy through one retirement at a time, when the Court is in recess, and during non-presidential election years suggests a concern for institutional health. Finally, if at all possible, justices seek to depart under favorable presidents and Senates to ensure that a like-minded successor will be appointed.

Currently, there is only one living retired Justice of the Supreme Court, Sandra Day O'Connor, who announced her intent to retire in 2005 and was replaced by Samuel Alito in 2006. As a retired Justice, Justice O'Connor may be, and has been, designated for temporary assignments to sit with several United States Courts of Appeals. Nominally, such assignments are made by the Chief Justice; they are analogous to the types of assignments that may be given to judges of lower courts who have elected senior status, except that a retired Supreme Court Justice never sits as a member of the Supreme Court itself.

| Name | Born | Appt. by | Conf. vote | First day | Senior Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

March 26, 1930 (age 79) in El Paso, Texas | Reagan | 99-0 | September 25, 1981 | January 31, 2006 |

Seniority and seating

During Court sessions, the Justices sit according to seniority, with the Chief Justice in the center, and the Associate Justices on alternating sides, with the most senior Associate Justice on the Chief Justice's immediate right, and the most junior Associate Justice seated on the left farthest away from the Chief Justice. Therefore, the current court sits as follows from left to right when looking at the bench from the perspective of a lawyer arguing before the Court: Breyer, Thomas, Kennedy, Stevens (most senior Associate Justice), Roberts (Chief Justice), Scalia, Souter, Ginsburg and Alito (most junior Associate Justice).

In the Justices' private conferences, the current practice is for Justices to speak and vote in order of seniority from the Chief Justice first to the most junior Associate Justice last. The most junior Associate Justice in these conferences is tasked with any menial labor the Justices may require as they convene alone, generally limited to answering the door of their conference room and serving coffee. In addition, it is the duty of the most junior Associate Justice to transmit the orders of the court after each private conference to the court's clerk. Justice Joseph Story served the longest as the junior Justice, from February 3, 1812, to September 1, 1823, for a total of 4,228 days. Justice Stephen Breyer follows close behind, falling just 29 days shy of Justice Story's record when Justice Samuel Alito joined the court on January 31, 2006.[11]

Salary

Associate justices of the Supreme Court are paid $208,100 per year as of 2008, and the chief justice receives $217,400 per year.[12]

Political leanings

While justices do not represent or receive official endorsements from political parties, as is accepted practice in the legislative and executive branches, jurists are informally categorized in legal and political circles as being judicial conservatives, moderates, or liberals. Such leanings, however, refer to legal outlook rather than a political or legislative one.

Seven of the current justices of the court were appointed by Republican presidents, while two were appointed by a Democratic president. It is popularly accepted that Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito compose the Court's conservative wing. Justices Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg and Breyer are generally thought of as the Court's liberal wing.[13] Justice Kennedy, generally thought of as a conservative who "occasionally vote[s] with the liberals", is considered most likely to be the swing vote that determines the outcome of certain close cases.[14]

Quarters

The Supreme Court first met on February 1, 1790, at the Merchants' Exchange Building in New York City, which then was the national capital. Philadelphia became the capital city later in 1790, and the Court followed Congress and the President there, meeting briefly in Independence Hall, and then from 1791 to 1800 at Old City Hall at 5th and Chestnut Streets. After Washington, D.C., became the capital in 1800, the Court occupied various spaces in the United States Capitol building until 1935, when it moved into its own purpose-built home at One First Street Northeast, Washington, DC. The four-story building was designed in a classical style sympathetic to the surrounding buildings of the Capitol complex and Library of Congress by architect Cass Gilbert, and is clad in marble quarried chiefly in Vermont. The building includes space for the Courtroom, Justices' chambers, an extensive law library, various meeting spaces, and auxiliary services such as workshop, stores, cafeteria and a gymnasium. The Supreme Court building is within the ambit of the Architect of the Capitol, but maintains its own police force, the Supreme Court Police, separate from the Capitol Police.

Jurisdiction

Section 2 of Article Three of the United States Constitution outlines the jurisdiction of the federal courts of the United States:

| “ | The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects. | ” |

The jurisdiction of the federal courts was further limited by the Eleventh Amendment, which forbade the federal courts from hearing cases "commenced or prosecuted against [a State] by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State." However, states may waive this immunity, and Congress may abrogate the states' immunity in certain circumstances (see Sovereign immunity). In addition to constitutional constraints, Congress is authorized by Article III to regulate the court's appellate jurisdiction: for example, the federal courts may consider "Controversies ... between Citizens of different states only if the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000; otherwise, the case may only be brought in state courts.

- Further information: diversity jurisdiction

Exercise of this power (for example, the Detainee Treatment Act, which provided that "'no court, justice, or judge' shall have jurisdiction to consider the habeas application of a Guantanamo Bay detainee")[15] can become controversial; see Jurisdiction stripping

The Constitution specifies that the Supreme Court may exercise original jurisdiction in cases affecting ambassadors and other diplomats, and in cases in which a state is a party. In all other cases, however, the Supreme Court has only appellate jurisdiction. The Supreme Court considers cases based on its original jurisdiction very rarely; almost all cases are brought to the Supreme Court on appeal. In practice, the only original jurisdiction cases heard by the Court are disputes between two or more states.

The power of the Supreme Court to consider appeals from state courts, rather than just federal courts, was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789 and upheld early in the Court's history, by its rulings in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816) and Cohens v. Virginia (1821). The Supreme Court is the only federal court that has jurisdiction over direct appeals from state court decisions, although there are a variety of devices that permit so-called "collateral review" of state cases.

Because, under Article III, federal courts may only entertain "cases" or "controversies", the Court avoids deciding cases that are moot and does not render advisory opinions, as the supreme courts of some states may do. For example, in DeFunis v. Odegaard, , the Court dismissed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a law school affirmative action policy because the plaintiff student had graduated since he began the lawsuit, and a decision from the Court on his claim would not be able to redress any injury he had suffered. The mootness exception is not absolute; if an issue is "capable of repetition yet evading review", the Court will address it even though the party before the Court would not himself be made whole by a favorable result. In Roe v. Wade, , and other abortion cases, the Court addresses the merits of claims pressed by pregnant women seeking abortions even if they are no longer pregnant because it takes longer to appeal a case through the lower courts to the Supreme Court than the typical human gestation period.

Justices as Circuit Justices

The United States is divided into thirteen circuit courts of appeals, each of which is assigned a "Circuit Justice" from the Supreme Court. Although this concept has been in continuous existence throughout the history of the republic, its meaning has changed through time.

Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, each Justice was required to "ride circuit," or to travel within the assigned circuit and consider cases alongside local judges. This practice encountered opposition from many Justices, who complained about the difficulty of travel. Moreover, several individuals opposed it on the grounds that a Justice could not be expected to be impartial in an appeal if he had previously decided the same case while riding circuit. Circuit riding was abolished in 1891. Today, the duties of a "Circuit Justice" are generally limited to receiving and deciding requests for stays in cases coming from the circuit or circuits to which the Justice is assigned, and other clerical tasks such as addressing certain requests for extensions of time. A Circuit Justice may (but in practice almost never does) sit as a judge of that circuit. When he or she does so, a Circuit Justice has seniority over the Chief Judge of that circuit.

The Chief Justice is traditionally assigned to the District of Columbia Circuit, the Federal Circuit and the Fourth Circuit, which includes Maryland and Virginia, the states surrounding the District of Columbia. Each Associate Justice is assigned to one or two judicial circuits.

After Justice Alito's appointment, circuits were assigned as follows:[16]

| For the D.C. Circuit, John G. Roberts, Jr. | For the Seventh Circuit, John Paul Stevens |

| For the First Circuit, David H. Souter | For the Eighth Circuit, Samuel A. Alito, Jr. |

| For the Second Circuit, Ruth Bader Ginsburg | For the Ninth Circuit, Anthony M. Kennedy |

| For the Third Circuit, David H. Souter | For the Tenth Circuit, Stephen G. Breyer |

| For the Fourth Circuit, John G. Roberts, Jr. | For the Eleventh Circuit, Clarence Thomas |

| For the Fifth Circuit, Antonin G. Scalia | For the Federal Circuit, John G. Roberts, Jr. |

| For the Sixth Circuit, John Paul Stevens |

The circuit assignments frequently, but do not always and need not, reflect the geographic regions where the assigned Justices served as judges or practitioners before joining the Supreme Court. Four of the current Justices are assigned to circuits on which they once sat as circuit judges: Chief Justice Roberts (D.C. Circuit), Justice Souter (First Circuit), Justice Stevens (Seventh Circuit), and Justice Kennedy (Ninth Circuit). Furthermore, Justices Thomas and Ginsburg are assigned to the circuits that include their home states (the Eleventh and Second Circuits, respectively).

How a case moves through the Court

The vast majority of cases come before the Court by way of petitions for writs of certiorari, commonly referred to as "cert". The Court may review any case in the federal courts of appeals "by writ of certiorari granted upon the petition of any party to any civil or criminal case".[17] The Court may only review "final judgments rendered by the highest court of a state in which a decision could be had" if those judgments involve a question of federal statutory or constitutional law.[18] The party that lost in the lower court is called the petitioner, and the party that prevailed is called the respondent. All case names before the Court are styled Petitioner v. Respondent, regardless of which party initiated the lawsuit in the trial court. For example, criminal prosecutions are brought in the name of the state and against an individual, as in State of Arizona v. Ernesto Miranda. If the defendant is convicted, and his conviction then is affirmed on appeal in the state supreme court, when he petitions for cert the name of the case becomes Miranda v. Arizona.

There are situations where the Court has original jurisdiction, such as when two states have a dispute against each other, or when there is a dispute between the United States and a state. In such instances, a case is filed with the Supreme Court directly. Examples of such cases include United States v. Texas, a case to determine whether a parcel of land belonged to the United States or to Texas, and Virginia v. Tennessee , a case turning on whether an incorrectly drawn boundary between two states can be changed by a state court, and whether the setting of the correct boundary requires Congressional approval.

The common shorthand name for cases is typically the first party (the petitioner). For example, Brown v. Board of Education is referred to simply as Brown, and Roe v. Wade as Roe. The exception to this rule is when the name of a state, or the United States, or some government entity, is the first listed party. In that instance, the name of the second party is the shorthand name. For example, Iowa v. Tovar is referred to simply as Tovar, and Gonzales v. Raich is referred to simply as Raich, because the first party, Alberto Gonzales, was sued in his official capacity as the United States Attorney General.

A cert petition is voted on at a session of the Court called a conference. A conference is a private meeting of the nine Justices by themselves; the public is not permitted to attend, and neither are the Justices' law clerks. If four Justices vote to grant the petition, then the case proceeds to the briefing stage; otherwise, the case ends. Except in death penalty cases and other cases in which the Court orders briefing from the respondent, the respondent may, but is not required to, file a response to the cert petition.

The Court grants a petition for certiorari only for "compelling reasons," spelled out in the court's Rule 10. Such reasons include, without limitation:

- to resolve a conflict in the interpretation of a federal law or a provision of the federal constitution

- to correct an egregious departure from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings

- to resolve an important question of federal law, or to expressly review a decision of a lower court that conflicts directly with a previous decision of the Court.

When a conflict of interpretations arises from differing interpretations of the same law or constitutional provision issued by different federal circuit courts of appeals, lawyers call this situation a "circuit split". If the Court votes to deny a cert petition, as it does in the vast majority of such petitions that come before it, it does so typically without comment. A denial of a cert petition is not a judgment on the merits of a case, and the decision of the lower court stands as the final ruling in the case.

To manage the high volume of cert petitions received by the Court each year (of the more than 7,000 petitions the Court receives each year, it will usually request briefing and hear oral argument in 100 or fewer), the Court employs an internal case management tool known as the "cert pool." Currently, all justices except for Justice Stevens and Justice Alito participate in the cert pool.[19][20][21]

When the Court grants a cert petition, the case is set for oral argument. At this point, both parties file briefs on the merits of the case, as distinct from reasons the parties may urge for granting or denying the cert petition. With the consent of the parties or approval of the Court, amici curiae may also file briefs. The Court holds two-week oral argument sessions each month from October through April. Each side has half an hour to present its argument, and during that time the Justices can and do interrupt the advocate and ask questions of their own. The petitioner goes first, and may reserve some time to rebut the respondent's arguments after the respondent has concluded. Amici curiae may also present oral argument on behalf of one party if that party agrees. The Court advises counsel to assume that the Justices are familiar with and have read the briefs filed in a case.

At the conclusion of oral argument, the case is submitted for decision. Cases are decided by majority vote of the Justices. It is the Court's practice to issue decisions in all cases argued in a particular Term by the end of that Term. Within that Term, however, the Court is under no obligation to release a decision within any set time after oral argument. At the conclusion of oral argument, the Justices retire to another conference at which the preliminary votes are tallied, and the most senior Justice in the majority assigns the initial draft of the Court's opinion to a Justice on his or her side. Drafts of the Court's opinion, as well as any concurring or dissenting opinions, circulate among the Justices until the Court is prepared to announce the judgment in a particular case.

It is possible that, through recusals or vacancies, the Court divides evenly on a case. If that occurs, then the decision of the court below is affirmed, but does not establish binding precedent. In effect, it results in a return to the status quo ante. For a case to be heard, there must be a quorum of at least six justices.[22] If, because of recusals and vacancies, there is no quorum to hear a case and a majority of qualified justices believes that the case cannot be heard and determined in the next term, then the judgment of the court below is affirmed as if the Court had been evenly divided. For cases brought directly to the Supreme Court by direct appeal from a United States District Court, the Chief Justice may order the case remanded to the appropriate U.S. Court of Appeals for a final decision there.[22]

The Court's opinions are published in three stages. First, a slip opinion is made available on the Court's web site and through other outlets. Next, a number of opinions are bound together in paperback form, called a preliminary print of United States Reports, the official series of books in which the final version of the Court's opinions appears. About a year after the preliminary prints are issued, a final bound volume of U.S. Reports is issued. The individual volumes of U.S. Reports are numbered so that may cite this set of reporters -- or a competing version published by another commercial legal publisher -- to allow those who read their pleadings and other briefs to find the cases quickly and easily.

At present there are 545 volumes of U.S. Reports. Lawyers use an abbreviated format to cite cases, in the form xxx U.S. xxx (yyyy). The number before the "U.S." refers to the volume number, and the number after the U.S. refers to the page within that volume. The number in parentheses is the year in which the case was decided. For instance, if a lawyer wanted to cite Roe v. Wade, decided in 1973, and which appears on page 113 of volume 410 of U.S. Reports, he would write 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

Checks and balances

The Constitution does not explicitly grant the Supreme Court the power of judicial review; nevertheless, the power of the Supreme Court to overturn laws and executive actions it deems unlawful or unconstitutional is a well-established precedent. Many of the Founding Fathers accepted the notion of judicial review; in Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton writes: "A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute." The Supreme Court first established its power to declare laws unconstitutional in Marbury v. Madison (1803), consummating the system of checks and balances.

The Supreme Court cannot directly enforce its rulings; instead, it relies on respect for the Constitution and for the law for adherence to its judgments. One notable instance of nonacquiescence came in 1832, when the state of Georgia ignored the Supreme Court's decision in Worcester v. Georgia. President Andrew Jackson, who sided with the Georgia courts, is supposed to have remarked, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!";[23] however, this quotation may be apocryphal. State militia in the South also resisted the desegregation of public schools after the 1954 judgment Brown v. Board of Education. More recently, many feared that President Richard Nixon would refuse to comply with the Court's order in United States v. Nixon (1974) to surrender the Watergate tapes. Nixon, however, ultimately complied with the Supreme Court's ruling.

The Constitution provides that the salary of a Justice may not be diminished during his or her continuance in office. This clause was intended to prevent Congress from punishing Justices for their decisions by reducing their emoluments. Together with the provision that Justices hold office for good behavior, this clause helps guarantee judicial independence.

Competing criticisms for partisanship and judicial activism

Judicial activism is the charge that judges are going beyond their powers and are making (instead of interpreting) the law. It is the antithesis of judicial restraint. Judicial activism is not restricted to any particular ideological or political point of view. American history has included periods in which the Supreme Court was accused of conservative judicial activism, and also of liberal activism.[24]

Howard Zinn presents the idea that the overall history of the Court, especially during the period between the Civil War and the Great Depression, should be viewed as one of mostly conservative activism in the defense of property rights. The case most often invoked as an example of conservative judicial activism is Lochner v. New York, a 1905 case that invalidated a New York law regulating the hours bakers could work as a violation of liberty of contract, a part of the doctrine of Substantive due process under the Fourteenth Amendment.[24] This decision elevated the concept of "liberty of contract" to a dogmatic stance of the Court for over thirty years.

On the other hand, starting primarily with the Supreme Court's 1961 decision in Mapp v. Ohio, which established the exclusionary rule in state criminal proceedings, many conservatives have portrayed the Supreme Court as a haven for liberal judicial activism. This has especially been the case since the advent of the Warren Court and the revolution in civil liberties, but the charge has continued to the Burger Court and even into the Rehnquist Court. The argument is that in the name of expanding the "rights" a majority of justices find agreeable, the Court is twisting the Constitution by disregarding the original meaning of the due process and equal protections clauses in order to reach a desired result. One case which is often invoked by critics as an example of liberal activism is Roe v. Wade in 1973, where the Court struck down restrictive abortion laws as violating the "right to privacy" that the Court had previously found inherent in the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[24]

According to Zinn, however, of the Courts extant in the 20th century, only the Stone, Vinson, Warren, and to a lesser extent the Burger Courts (a time frame ranging approximately from 1941 to 1986) could be seen as leaning more toward a liberal interpretation of the Constitution and its guarantees, but not in every opinion.[25]

Liberal and conservative activism are both, at least as perceived by their opponents, abandoning the literal words of the Constitution in pursuit of what the Supreme Court considers to be the just or right or reasonable course of action. A campaign against judicial activism has been part of presidencies of many diverse ideological viewpoints, such as those of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan.

In 1988 President Ronald Reagan lectured a convention of attorneys about, “…courts that played fast and loose with the instrument the founding fathers devised. Yes, some law professors and judges said the courts should save the country from the Constitution. We said it was time to save the Constitution from them.”[26]

President Abraham Lincoln (referring to the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision) warned:

If the policy of the government, upon vital questions affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court...the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned the government into the hands of that eminent tribunal. (Lincoln's First Inaugural Address, 1861).

In Coercing Virtue: The Worldwide Rule of Judges (2003), Judge Robert Bork, argues:

What judges have wrought is a coup d'état, – slow-moving and genteel, but a coup d'état nonetheless…. The nations of the West are increasingly governed not by law or elected representatives, but by unelected, unrepresentative, unaccountable committees of lawyers applying no law other than their own will.[27]

In recent years, the term "judicial usurpation" has been used by many to describe what they consider to be aggressive judicial activism. During the two years following the publication of Bork's book, no less than five books appeared on the subject of judicial usurpation.[28] In 2005, Pat Buchanan chronicled what he believed to be the Warren court's transgressions:

The Brown decision of 1954, desegregating the schools of 17 states and the District of Columbia, awakened the nation to the court's new claim to power. Hailed by liberal elites – and finding no resistance from a Democratic Congress or president who spent his afternoons at Burning Tree – Warren's court went off on a rampage. It invented new rights for criminals and put new restrictions on cops and prosecutors. It reassigned students to schools by race and ordered busing to bring it about, tearing cities apart. It ordered God, prayer and Bible-reading out of classrooms. It said pornography was constitutionally protected, making Larry Flynt and Al Goldstein First Amendment heroes, rather than felons. It ruled naked dancing a protected form of free expression. It declared abortion a constitutional right and sodomy constitutionally protected behavior. It outlawed the death penalty, abolished terms limits on members of Congress voted by state referendums, and told high school coaches to stop praying in locker rooms and students to stop saying prayers at graduation. It ordered the Ten Commandments out of schoolhouses and courthouses. It condoned discrimination against white students in violation of the 14th Amendment's guarantee of equal protection. And, two weeks ago, in a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that towns can seize private homes and turn them over to private developers.[29]

Quotations

- "I had never before argued a Supreme Court case on my own. Since arguments in that court are thirty minutes in length per side, and since most of the time consumed in argument is taken up with responses to questions of the Court, Dean [Ringel] and I devoted most of our preparation to three overlapping issues, ones that have consumed my attention in every later Supreme Court argument as well. The first was jurisprudential in nature. What rule of law were we urging the Court to adopt? How would it apply in any future case? What would be its impact on First Amendment legal doctrine?" --Floyd Abrams, discussing his argument before the Court in Landmark Communications v. Virginia.[30]

- "In the United States at the present day, the reverence which the Greeks gave to the oracles and the Middle Ages to the Pope is given to the Supreme Court. Those who have studied the working of the American Constitution know that the Supreme Court is part of the forces engaged in the protection of the plutocracy. But of the men who know this, some are on the side of the plutocracy, and therefore do nothing to weaken the traditional reverence for the Supreme court, while others are discredited in the eyes of the ordinary quiet citizens by being said to be subversive and Bolshevik." -- Bertrand Russell in, Power, Routledge Classics, 2004: p.53.[31]

Visiting the Court

The United States Supreme Court building is open to the public from 9am - 4:30pm, Monday through Friday. The court is closed on Saturdays, Sundays and United States federal holidays. The Supreme Court building is located at 1 First Street NE in Washington D.C directly across from the east entrance (opposite side from the Mall) of the United States Capitol. When the court is in session, visitors are seated in the gallery on a first come, first seated basis.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Federal judicial appointment history

- History of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by court composition

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by education

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by seat

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by time in office

- Lists of United States Supreme Court cases

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law schools by United States Supreme Court Justices trained

- Segal-Cover score

- Unsuccessful nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States

Notes

- ↑ "U.S. Constitution, Article III, Section 1". Retrieved on 2007-09-21.

- ↑ See, in dicta Northern Pipeline Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., 458 U.S. 50, 59 (1982); United States ex rel. Toth v. Quarles, 350 U.S. 11, 16 (1955).

- ↑ "A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. Retrieved on 2007-09-21.

- ↑ History of the Court, in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (eds) The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- ↑ In Steps Big and Small, Supreme Court Moved Right by Linda Greenhouse, New York Times, July 1, 2007.

- ↑ Justices, Number of. in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (editors), The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press 1992, ISBN 0-19-505935-6.

- ↑ Todd S., Purdum (July 5, 2005). "Presidents, Picking Justices, Can Have Backfires", Courts in Transition: Nominees and History, New York Times, p. A4. Retrieved on 2006-04-24.

- ↑ "United States Senate. "Nominations"".

- ↑ Balkin, Jack M.. "The passionate intensity of the confirmation process" (HTML). Jurist. Retrieved on 2008-02-13.

- ↑ David N. Atkinson, Leaving the Bench (University Press of Kansas 1999)ISBN 0-7006-0946-6.

- ↑ "Breyer Just Missed Record as Junior Justice". Retrieved on 2008-01-11.

- ↑ "U.S. Supreme Court Justices". Retrieved on 2008-04-24.

- ↑ In a 2007 interview, Justice Stevens stated he considers himself a "judicial conservative", and only appears liberal because he has been surrounded by increasingly conservative colleagues.""The Dissenter"" (HTML). The Times Magazine. New York Times (2007-09-23). Retrieved on 2008-02-14.

- ↑ Lane (2006-01-31). "Kennedy Seen as The Next Justice In Court's Middle" (HTML). The Washington Post.

- ↑ Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (Scalia, J., dissenting) [1]

- ↑ "Supreme Court orders" (PDF) (2006-02-01). Retrieved on 2008-02-13.

- ↑

- ↑ ; see also Adequate and independent state grounds

- ↑ Tony Mauro (2005-10-21). "Roberts Dips Toe Into Cert Pool" (HTML). Legal Times. Retrieved on 2007-10-31.

- ↑ Tony Mauro (2006-07-04). "Justice Alito Joins Cert Pool Party" (HTML). Legal Times. Retrieved on 2007-10-31.

- ↑ Adam Liptak (2008-09-25). "A Second Justice Opts Out of a Longtime Custom: The 'Cert. Pool'" (HTML). New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1

- ↑ The American Conflict by Horace Greeley (1873), p. 106; also in The Life of Andrew Jackson (2001) by Robert Vincent Remini

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 See for example Judicial activism in The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, edited by Kermit Hall; article written by Gary McDowell.

- ↑ Irons, Peter. A People's History of the Supreme Court. London: Penguin, 1999. ISBN 0670870064

- ↑ Special keynote address by President Ronald Reagan, November 1988, at the second annual lawyers convention of the Federalist Society, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Robert Bork, Coercing Virtue, The Worldwide Rule of Judges (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute Press, 2003), pp. 13 & 9.

- ↑ Judge Andrew Napolitano, Constitutional Chaos : What Happens When the Government Breaks Its Own Laws (Nashville TN: Nelson Current, 2004); Phyllis Schlafly, The Supremacists: The Tyranny of Judges and How to Stop It (Dallas, TX: Spence Publishing Company, 2004); Mark R. Levin, Men in Black: How the Supreme Court is Destroying America (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishers, 2005); Judge Roy Moore with John Perry, So Help Me God: The Ten Commandments, Judicial Tyranny, And The Battle For Religious Freedom (Nashville TN: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2005); Mark Sutherland, et. al.., Judicial Tyranny: the new kings of America (St. Louis, MO: Amerisearch , 2005).

- ↑ Patrick J. Buchanan, “The Judges War: an Issue of Power,” Townhall.com, July 6, 2005.

- ↑ Floyd Abrams, quoted in his book, Speaking Freely (2005), p. 65.

- ↑ Written by Bertrand Russell in 1937.

References

- Biskupic, Joan and Elder Witt. (1997). Congressional Quarterly's Guide to the U.S. Supreme Court. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly. ISBN 1-56802-130-5

- The Constitution of the United States.

- Hall, Kermit et al. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harvard Law Review Assn., (2000). The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation, 17th ed. [18th ed., 2005. 13-ISBN 978-6-0001-4329-9 10-ISBN 6-0001-4329-X]

- Irons, Peter. (1999). A People's History of the Supreme Court. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-87006-4.

- Rehnquist, William. (1987). The Supreme Court. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40943-2.

- The Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States (2005 ed.) (pdf).

- Skifos, Catherine Hetos. (1976)."The Supreme Court Gets a Home", Supreme Court Historical Society 1976 Yearbook. [in 1990, re-named The Journal of Supreme Court History (ISSN 1059-4329)]

- Warren, Charles. (1924). The Supreme Court in United States History. (3 volumes). Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

- Woodward, Bob and Scott Armstrong. (1979). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Supreme Court Historical Society. "The Court Building" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-02-13.

Further reading

- Beard, Charles A. (1912). The Supreme Court and the Constitution. New York: Macmillan Company. Reprinted Dover Publications, 2006. ISBN 0-486-44779-0.

- Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) ISBN 0791013774, ISBN 978-0791013779

- Garner, Bryan A. (2004). Black's Law Dictionary. Deluxe 8th ed. Thomson West. ISBN 0-314-15199-0.

- Greenburg, Jan. (2007). Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control for the United States Supreme Court. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-101-1.

- McCloskey, Robert G. (2005). The American Supreme Court. 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-55682-4.

- Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine: Inside the secret world of the Supreme Court. Doubleday, 2007. ISBN 0-385-51640-1.

- Urofsky, Melvin and Finkelman. (2001). A March of Liberty: A Constitutional History of the United States. 2 vols. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512637-8 & ISBN 0-19-512635-1.

External links

- Supreme Court of the United States. Official Homepage.

- The Supreme Court Historical Society. Official Homepage.

- Legal Information Institute Supreme Court Collection.

- FindLaw Supreme Court Opinions.

- Oyez Project Supreme Court Multimedia.

- U.S. Supreme Court Decisions (v. 1+) Justia, Oyez and U.S. Court Forms.

- Supreme Court Records and Briefs - Cornell Law Library

- History of the U.S. Supreme Court

- Milestone Cases in Supreme Court History.

| Supreme Court of the United States | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||