Romance languages

| Romance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Originally Southern Europe; now also Latin America, Quebec,Parts of Lebanon and Israel and much of Western Africa | ||

| Genetic classification: |

Indo-European Italic Romance |

||

| Subdivisions: |

Italo-Western

Eastern Romance

Southern Romance

|

||

| ISO 639-2: | roa | ||

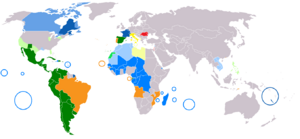

Distribution of major Romance languages:

|

|||

|

Indo-European topics |

|---|

| Indo-European languages |

| Albanian · Armenian · Baltic Celtic · Germanic · Greek Indo-Iranian (Indo-Aryan, Iranian) Italic · Slavic extinct: Anatolian · Paleo-Balkans (Dacian, |

| Indo-European peoples |

| Albanians · Armenians Balts · Celts · Germanic peoples Greeks · Indo-Aryans Iranians · Latins · Slavs historical: Anatolians (Hittites, Luwians) |

| Proto-Indo-Europeans |

| Language · Society · Religion |

| Urheimat hypotheses |

| Kurgan hypothesis Anatolia · Armenia · India · PCT |

| Indo-European studies |

The Romance languages (sometimes referred to as Romanic languages, or Neolatin languages) are a branch of the Indo-European language family comprising all the languages that descend from Latin, the language of ancient Rome. They have more than 700 million native speakers worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Africa, as well as many smaller regions scattered throughout the world.

Romance languages have their roots in Vulgar Latin, the popular sociolect of Latin spoken by soldiers, settlers and merchants of the Empire, as distinguished from the Classical form of the language spoken by the Roman upper classes, the form in which the language was generally written. Between 350 BC and 150 AD, the expansion of the Empire, together with its administrative and educational policies, made Latin the dominant native language in continental Western Europe. Latin also exerted a strong influence in southeastern Britain, the Roman province of Africa, and the Balkans north of the Jireček Line.

During the Empire's decline, and after its fragmentation and collapse in the 5th century, dialects of Latin began to diverge within each local area at an accelerated rate, and eventually evolved into languages of their own right. The overseas empires established by France, Portugal and Spain from the 15th century onward spread their languages to the other continents, to such an extent that about 70% of all Romance speakers today live outside Europe.

Despite influences from pre-Roman languages and from later invasions, the phonology, morphology, lexicon, and syntax of all Romance languages are predominantly evolutions of Vulgar Latin. In particular, with only one or two exceptions, Romance languages have lost the declension system of Classical Latin and, as a result, have SVO sentence structure and make extensive use of prepositions.

Contents |

Name

The term "Romance" comes from the Vulgar Latin adverb romanice, derived from Romanicus: for instance, in the expression romanice loqui, "to speak in Roman" (that is, the Latin vernacular), contrasted with latine loqui, "to speak in Latin" (Medieval Latin, the conservative version of the language used in writing and formal contexts or as a lingua franca), and with barbarice loqui, "to speak in Barbarian" (the non-Latin languages of the peoples that conquered the Roman Empire).[1] From this adverb the noun romance originated, which applied initially to anything written romanice, or "in the Roman vernacular".

The word romance with the modern sense of romance novel or love affair has the same origin. In the medieval literature of Western Europe, serious writing was usually in Latin, while popular tales, often focusing on love, were composed in the vernacular and came to be called "romances".

Sample

Lexical and grammatical similarities among the Romance languages, and between Latin and each of them, are apparent from the following examples:

-

Latin (Illa) claudit semper fenestram antequam cenat. Aragonese Ella tranca/zarra siempre la finestra antis de zenar. Asturian Ella pieslla siempre la ventana/feniestra primero de cenar. Bergamasque (Eastern Lombard) (Lé) la sèra sèmper sö la finèstra prima de senà. Catalan Ella tanca sempre la finestra abans de sopar. Franco-Provençal (Arpitan) (Le) sarre toltin/tojor la fenétra avan de goutâ/dinar/sopar. French Elle ferme toujours la fenêtre avant de dîner/souper. Galician Ela pecha sempre a fiestra/xanela antes de cear. Italian (Lei) chiude sempre la finestra prima di cenare. Leonese Eilla pecha siempres la ventana primeiru de cenare. Milanese (Western Lombard) (Lee) la sara semper su la finestra primma de disnà. Mirandese Eilha cerra siempre la bentana/jinela atrás de jantar. Neapolitan Chella sempre chiud' 'a fenesta prima 'e mangià. Occitan Ela barra sempre la fenèstra abans de sopar. Piedmontese Chila a sara sèmper la fnestra dnans da fé sin-a. Portuguese (Brazil) Ela sempre fecha a janela antes de jantar. Portuguese (Portugal) Ela fecha sempre a janela antes de jantar. Romanian Ea închide totdeauna fereastra înainte de cina. Romansh Ella clauda/serra adina la fanestra avant ch'ella tschainia. Corsican Ella chjudi sempre u purtellu primma di cenà. Sardinian Issa serrat semper sa bentana antes de chenare. Sicilian Idda chiu(d)i sempri la finestra àntica pistìa. Spanish Ella cierra siempre la ventana antes de cenar. Venetian Ła sera sempre ła finestra prima de senar. Walloon Ele sere todi li finiesse divant di soper. Translation She always closes the window before dining.

As an alternative to lei (originally the accusative form), Italian has the pronoun ella, a cognate of the other words for "she", but it has become disused in most dialects.

Spanish/Asturian/Leonese ventana and Mirandese and Sardinian bentana comes from Latim ventum, Spanish viento, "wind" and Portuguese janela, Galician xanela, Mirandese jinela from Latin ianua + ella, "small opening", same root as "January" and "janitor".

Note that some of the lexical divergence above comes from different Romance languages using the same root word with different meanings (semantic change). Portuguese, for example, has the word fresta, which is a cognate of French fenêtre, Italian finestra, Romanian fereastra and so on, but now means "slit" as opposed to "window." The Portuguese terms defenestrar, meaning "to throw through a window" and fenestrada, "replete with windows" also have the same root. Likewise, Portuguese also has the word cear, a cognate of Italian cenare and Spanish cenar, but uses it in the sense of "to have a late supper" in most dialects, while the preferred word for "to dine" is actually jantar (related to archaic Spanish yantar) because of semantic changes in the 19th century. Galician has both fiestra (from medieval fẽestra which is the ultimate origin of standard Portuguese fresta), and the less frequently used ventá and xanela.

Sardinian balcone (alternative for bentana) comes from Old Italian and has a Germanic origin, as well as, English balcony, French balcon, Portuguese balcão, Romanian balcon, Spanish balcón and Corsican balconi (alternative for purtellu).

History

Vulgar Latin

There is a lack of documentary evidence about Vulgar Latin for the purposes of comprehensive research, and the literature is often hard to interpret or generalise upon. Many of its speakers were soldiers, slaves, displaced peoples and forced resettlers, more likely to be natives of conquered lands than natives of Rome. It is believed that Vulgar Latin already had most of the features that are shared by all Romance languages, which distinguish them from Classical Latin, such as the almost complete loss of the Latin case system and its replacement by prepositions; the loss of the neuter gender, comparative inflections, and many verbal tenses; the use of articles; and the initial stages of the palatalization of the plosives c, g, and t. There are some modern languages, such as Finnish, which have similar, quite sharp, differences between their printed and spoken form. This perhaps suggests that the form of Vulgar Latin that evolved into the Romance languages was around during the time of the empire, and was spoken alongside the written Classical Latin, reserved for official and formal occasions.

Fall of the Roman Empire

During the political decline of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, there were large-scale migrations into the empire, and the Latin-speaking world was fragmented into several independent states. Central Europe and the Balkans were occupied by the Germanic and Slavic tribes, as well as by the Huns, which isolated the Vlachs from the rest of Latin Europe. Latin disappeared completely from southeastern Britain and the Roman province of Africa, where it had been spoken by much of the urban population. But the Germanic tribes that had penetrated Italy, Gaul, and Hispania eventually adopted Latin and the remnants of Roman culture, and so Latin remained the dominant language there.

Latent incubation

Between the fifth and tenth centuries, the dialects of spoken Vulgar Latin diverged in various parts of their domain, eventually becoming distinct languages. This evolution is poorly documented because the literary language, Medieval Latin, remained close to the older Classical Latin.

Recognition of the vernaculars

Between the 10th and 13th centuries, some local vernaculars developed a written form and began to supplant Latin in many of its roles. In some countries, such as Portugal, this transition was expedited by force of law; whereas in others, such as Italy, many prominent poets and writers used the vernacular of their own accord.

Uniformization and standardization

The invention of the press apparently slowed down the evolution of Romance languages from the 16th century on, and brought a tendency towards greater uniformity of standard languages within political boundaries, at the expense of other Romance languages and dialects less favored politically. In France, for instance, the dialect spoken in the region of Paris gradually spread to the entire country, and the Occitan of the south lost ground.

Current status

The Romance language most widely spoken natively today is Spanish, followed by Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian and Catalan, all of which are official languages in at least one country. A few other languages have official status on a regional or otherwise limited level, for instance Friulian, Sardinian and Valdôtain in Italy; Romansh in Switzerland; and Galician in Spain. French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Romanian are also official languages of the European Union. Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian, and Catalan are the official languages of the Latin Union; and French and Spanish are two of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Outside Europe, French, Spanish and Portuguese are spoken and enjoy official status in various countries that emerged from their respective colonial empires. French is an official language of Canada, Haiti, many countries in Africa, and some in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, as well as France's current overseas possessions. Spanish is an official language of Mexico, much of South America, Central America and the Caribbean, and of Equatorial Guinea in Africa. Portuguese is the official language of Brazil, being the most spoken language in South America, and official in six African countries. Although Italy also had some colonial possessions, its language did not remain official after the end of the colonial domination, resulting in Italian being spoken only as a minority or secondary language by immigrant communities in North and South America and Australia or African countries like Libya, Eritrea and Somalia. Romania did not establish a colonial empire, but the language spread outside of Europe through emigration, notably in Western Asia; Romanian has flourished in Israel, where it is spoken by some 5% of the total population as mother tongue,[2] and by many more as a secondary language, considering the large population of Romanian-born Jews who moved to Israel after World War II.[3]

The total native speakers of Romance languages are divided as follows (with their ranking within the languages of the world in brackets):[4]

- Spanish 47% (2nd)

- Portuguese 26% (6th)

- French 11% (11th)

- Italian 9% (18th)

- Romanian 4% (34th)

- Catalan 1% (93rd)

- Others 2%

The remaining Romance languages survive mostly as spoken languages for informal contact. National governments have historically viewed linguistic diversity as an economic, administrative or military liability, as well a potential source of separatist movements; therefore, they have generally fought to eliminate it, by extensively promoting the use of the official language, restricting the use of the "other" languages in the media, characterizing them as mere "dialects", or even persecuting them.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, however, increased sensitivity to the rights of minorities have allowed some of these languages to start recovering their prestige and lost rights. Yet it is unclear whether these political changes will be enough to reverse the decline of minority Romance languages.

The classification of the Romance languages is inherently difficult, since most of the linguistic area can be considered a dialect continuum, and in some cases political biases can come into play. Nevertheless, according to SIL counts, 47 Romance languages and dialects are spoken in Europe. Along with Latin (which is not included among the Romance languages) and a few extinct languages of ancient Italy, they make up the Italic branch of the Indo-European family.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Classical Latin |

|

|

|

Vulgar Latin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continental Romance |

|

|

|

|

|

Sardinian dialects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Italo-Western Romance |

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern Romance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western Romance |

|

|

|

|

|

Proto-Italian |

|

Balkan Romance |

|

Dalmatian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Ibero-Romance |

|

|

|

|

|

Gallo Romance |

|

Italian |

|

Proto-Romanian |

|

Albanian words | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese |

|

Spanish |

|

French |

|

Occitano Romance |

|

Romanian |

|

Aromanian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Occitan |

|

Catalan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note that Dalmatian is now generally grouped under Proto-Italian rather than Eastern Romance.

Proposed subfamilies

The main subfamiles that have been proposed by Ethnologue within the various classification schemes for Romance languages are:

- Italo-Western, the largest group which includes languages such as Italian, Spanish, and French.

- Eastern Romance, which includes the Romance languages of Eastern Europe, such as Romanian.

- Southern Romance, which includes a few languages with particularly archaic features, such as Sardinian and, partially, Corsican.

Pidgins, creoles, and mixed languages

Some Romance languages have developed varieties which seem dramatically restructured as to their grammars or to be mixtures with other langues. It is not always clear whether they should be classified as Romance, pidgins, creole languages, or mixed languages.

Auxiliary and constructed languages

Latin and the Romance languages have also served as the inspiration and basis of numerous auxiliary and constructed languages, such as Interlingua, its reformed version Modern Latin,[5] Latino sine flexione, Occidental, Lingua Franca Nova, Ido and Esperanto, as well as languages created for artistic purposes only, such as Brithenig, Wenedyk and Talossan.

Linguistic features

Common Indo-European features

As members of the Indo-European family, Romance languages have a number of features that are shared with other members of this family, and in particular with English; but which set them apart from languages of other families, including:

- Almost all their words are classified into four major classes — nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs — each with a specific set of possible syntactic roles.

- Nouns, adjectives, determiners and some pronouns inflect according to grammatical gender and grammatical number.

- Inflection is normally marked with suffixes.

- A variety of grammatical distinctions are expressed on verbs (either through inflection or compounding), such as:

- Person and number;

- Tense, mood, and aspect.

- Voice.

- They are verb-centered; meaning that the basic clause structure consists of a verb, expressing an action involving one or more nouns — the arguments of the verb — that play specific semantic roles in the action and specific syntactic roles in the clause.

- They are fusional, nominative-accusative languages.

Features inherited from Classical Latin

The Romance languages share a number of features that were inherited from Classical Latin, and collectively set them apart from most other Indo-European languages:

- Word stress remains predominantly on the penultimate syllable in most languages, although there have been significant changes with respect to classical Latin. An exception is French, whose stress is fixed, falling predictably on the last syllable that does not contain a schwa. Stress patterns of similar languages usually match each other perfectly. French is the noticeable exception, as stress almost always falls on the last syllable.

- They have two grammatical numbers, singular and plural (no dual).

- In most languages, personal pronouns have different forms according to their grammatical function in a sentence, a remnant of the Latin case system; there is usually a form for the subject (inherited from the Latin nominative) another for the object (from the accusative or the dative), and a third set of personal pronouns used after prepositions or in stressed positions (see Prepositional pronoun and Disjunctive pronoun, for further information). Third person pronouns often have different forms for the direct object (accusative), the indirect object (dative), and the reflexive.

- Most are null-subject languages. French is a notable exception.[6]

- Verbs have many conjugations, including in most languages:

- A present tense, a preterite, an imperfect, a pluperfect and a future tense in the indicative mood, for statements of fact.

- Present and preterite subjunctive tenses, for hypothetical or uncertain conditions. Several languages (for example, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish) have also imperfect and pluperfect subjunctives.

- An imperative mood, for direct commands.

- Three non-finite forms: infinitive, gerund, and past participle.

- Distinct active and passive voices, as well as an impersonal passive voice.

- Several tenses, especially of the indicative mood, have been preserved with little change in most languages, as shown in the following table for the Latin verb dīcere (to say), and its descendants.

-

Infinitive Indicative Subjunctive Imperative Present Preterite Imperfect Present Present Latin dīcere dīcit dīxit dicēbat dīcat/dīcet dīc Aragonese dizir diz dizié deziba diga diz Asturian dicir diz dixo dicía diga di Catalan dir diu digué/va dir deia digui/diga digues French dire il dit il dit il disait il dise dis Galician dicir di dixo dicía diga di Italian dire dice disse diceva dica di' Leonese dicire diz dixu dicía diga di Milanese dì el dis l'ha dit el diseva el diga dì Neapolitan dicere dice dicette diceva Occitan dire1 ditz diguèt disiá diga diga Piedmontese dì a dis a dìsser2 a disìa a disa dis Portuguese dizer diz disse dizia diga diz3 Romanian a zice zice zise zicea zică zi Romansh dir el di (el ha ditg) el scheva4 ch'el dia di Sicilian dìciri dici dissi dicìa dicissi5 dici Spanish decir dice dijo decía diga di Venetian dir dixe dise dixea diga dì Walloon dire i dit (il a dit) i dijheut (k') i dixhe di Basic meaning to say he says he has said he used to say [that] he may say say! [you]

- 1With the variant díser.

- 2Until the 18th century.

- 3With the disused variant dize.

- 4From a form like discheva.

- 5Sicilian uses imperfect subjunctive in place of present subjunctive (dica).

- The main tense and mood distinctions that were made in classical Latin are generally still present in the modern Romance languages, though many are now expressed through compound rather than simple verbs. The passive voice, which was mostly synthetic in classical Latin, has been completely replaced with compound forms.

Features inherited from Vulgar Latin

Romance languages also have a number of features that are not shared with Classical Latin. Most of these are thought to have been inherited from Vulgar Latin. Even though the Romance languages are all derived from Latin, they are arguably much closer to each other than to their common ancestor, owing to a core of common developments. The main difference is the loss of the case system of Classical Latin, an essential feature which allowed great freedom of word order, and has no counterpart in any Romance language except Romanian. In this regard, the distance between any modern Romance language and Latin is comparable to that between Modern English and Old English. While speakers of French, Italian or Spanish, for example, can quickly learn to see through the phonological changes reflected in spelling differences, and thus recognize many Latin words, they will often fail to understand the meaning of Latin sentences.

- Vulgar Latin borrowed many words, often from Germanic languages that replaced words from Classical Latin during the Migration Period, including some basic vocabulary. Notable examples are *blancus (white), which replaced Classical Latin albus in most major languages; *guerra (war), which replaced bellum; and the words for the cardinal directions, where cognates of English "north", "south", "east" and "west" replaced the Classical Latin words borealis (or septentrionalis), australis (or meridionalis), orientalis, and occidentalis, respectively, in the vernacular. (See History of French - The Franks.)

- There are definite and indefinite articles, derived from Latin demonstratives and the numeral unus (one).

- Nouns have only two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine. Most Latin neuter nouns became masculine nouns in Romance. However, in Romanian, one class of nouns—including the descendants of many Latin neuter nouns—behave like masculines in the singular and feminines in the plural (e.g. un deget "one finger" vs două degete "two fingers", cf. Latin digitum, pl. digita). The same phenomenon is observed non-productively in Italian (e.g. il dito "the finger" vs le dita "the fingers").

- Apart from gender and number, nouns, adjectives and determiners are not inflected. Cases have generally been lost, though a trace of them survives in the personal pronouns. An exception is Romanian, which retains a combined genitive-dative case.

- Adjectives generally follow the noun they modify.

- Many Latin combining prefixes were incorporated in the lexicon as new roots and verb stems, e.g. Italian estrarre (to extract) from Latin ex- (out of) and trahere (to drag).

- Many Latin constructions involving nominalized verbal forms (e.g. the use of accusative plus infinitive in indirect discourse and the use of the ablative absolute) were dropped in favor of constructions with subordinate clause. Exceptions can be found in Italian, for example, Latin tempore permittente > Italian tempo permettendo; L. hoc facto > I. fatto ciò.

- The normal clause structure is SVO, rather than SOV, and is much less flexible than in Latin.

- Owing to sound changes which made it homophonous with the preterite, the Latin future indicative tense was dropped, and replaced with a periphrasis of the form infinitive + present tense of habēre (to have). Eventually, this structure was reanalysed as a new future tense.

- In a similar process, an entirely new conditional form was created.

- While the synthetic passive voice of classical Latin was abandoned in favour of periphrastic constructions, most of the active voice remained in use. However, several tenses have changed meaning, especially subjunctives. For example:

- The Latin pluperfect indicative became a conditional in Catalan and Sicilian, and an imperfect subjunctive in Spanish.

- The Latin pluperfect subjunctive developed into an imperfect subjunctive in all languages except Romansh, where it became a conditional, and Romanian, where it became a pluperfect indicative.

- The Latin preterite subjunctive, together with the future perfect indicative, became a future subjunctive in Old Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician.

- The Latin imperfect subjunctive became a personal infinitive in Portuguese and Galician.

- Many Romance languages have two verbs "to be", derived from the Latin stare (mostly used for temporary states) and esse (mostly used for essential attributes). In French, however, stare and esse had become ester and estre by the late Middle Ages. Owing to phonetic developments, there were the forms êter and être, which eventually merged to être, and the distinction was lost. In Italian, the two verbs share the same past participle, stato. See Romance copula, for further information.

For a more detailed illustration of how the verbs have changed with respect to classical Latin, see Romance verbs.

Sound changes

The vocabularies of Romance languages have undergone considerable change since their birth, by various phonological processes that were characteristic of each language. Those changes applied more or less systematically to all words, but were often conditioned by the sound context, morphological structure, or regularizing tendencies.

Most languages have lost sounds from the original Latin words. French, in particular, elision progressed more than in any other of the languages (although its conservative etymological spelling does not always make this apparent). In general, all final vowels were dropped, and sometimes also the preceding consonant: thus Latin lupus and luna became Italian lupo and luna but French loup [lu] and lune [lyn]. (See also Use of the circumflex in French.) Catalan, Occitan, many Northern Italian dialects, and Romanian (Daco-Romanian) lost the final vowels in most masculine nouns and adjectives, but retained them in the feminine. Other languages, including Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Galician and Romanian have retained those vowels.

Some languages have lost the final vowel -e from verbal infinitives, e.g. dīcere → Portuguese dizer (to say). Other common cases of apocope are the verbal endings, e.g. Latin amāt → Italian ama (he loves), amābam → amavo (I loved), amābat → amava (he loved), amābatis → amavate (you loved), etc.

Sounds were often lost in the middle of words, too; e.g. Latin Luna → Galician and Portuguese Lua (Moon), crēdere → Spanish creer (to believe).

On the other hand, some languages have added epenthetic vowels to words in certain contexts. Characteristic of the Iberian Romance languages is the insertion of a prosthetic e at the start of Latin words that began with s + consonant, such as sperō → espero (I hope). French originally did the same, but later dropped the s: spatula → arch. espaule → épaule (shoulder). In the case of Italian, a special article, lo for the definite and uno for the indefinite, is used for masculine words that begin with s + consonant words (sbaglio, "mistake" → lo sbaglio, "the mistake"), as well as all masculine words beginning with z (i.e. clusters /ts/ or /dz/) zaino, "backpack" → lo zaino, "the backpack".

A characteristic feature of the writing systems of almost all Romance languages is that the Latin letters c and g — which originally always represented the "hard" consonants /k/ and /g/ respectively — now represent "soft" consonants when they come before e, i, or y. This is due to a general palatalization of /k/ and /ɡ/ that occurred in the transition to Vulgar Latin. Since the written form of all the affected words was tied to the classical language, the shift was accommodated by a change in the pronunciation rules. The soft sounds of c and g vary from language to language. The consonant t, which was also palatalized, changes pronunciation in French (and English) orthography, but in the other Romance languages the spelling was altered to match the new sound. An exception is Sardinian, whose plosives remained hard before e and i in many words.

The distinctions of vowel length present in Classical Latin were lost in most Romance languages (an exception is Friulian), and partly replaced with qualitative contrasts such as monophthong versus diphthong (Italian, Spanish; French to a lesser extent), or close vowel versus open vowel (as in Portuguese, Galician, Occitan and Catalan).

For most languages in this family, consonant length is no longer phonemically distinctive or present. However some languages of Italy (Italian, Sardinian and Sicilian) do have long consonants like /bb/, /kk/, /dd/, etc., where the doubling indicates a short hold before the consonant is released, in many cases with distinctive lexical value: e.g. note /ˈnɔ.te/ (notes) vs. notte /ˈnɔt.te/ (night), cade /ˈka.de/ (s/he, it falls) vs. cadde /ˈkad.de/ (s/he, it fell). They may even occur at the beginning of words in Romanesco, Neapolitan and Sicilian, and are occasionally indicated in writing, e.g. Sicilian cchiù (more), and ccà (here). In general, the consonants /b/, /ts/, and /dz/ are long at the start of a word, while the archiphoneme |R| is realised as a trill /r/ in the same position.

The double consonants of Piedmontese exist only after stressed /ə/, written ë, and are not etymological: vëdde (Latin videre, to see), sëcca (Latin sicca, dry, feminine of sech). In standard Catalan and Occitan, there exists a geminate sound /lː/ written ŀl (Catalan) or ll (Occitan), but it is usually pronounced as a simple sound in colloquial (and even some formal) speech in both languages.

For more detailed descriptions of sound changes, see the articles Vulgar Latin, History of French, History of Portuguese, Latin to Romanian sound changes, and History of the Spanish language.

Lexical stress

While word stress was rigorously predictable in classical Latin, this is no longer the case in most Romance languages, and stress differences can be enough to distinguish between words. For example, Italian Papa [ˈpa.pa] (Pope) and papà [pa.ˈpa] (daddy), or the Spanish imperfect subjunctive cantara ([if he] sang) and future cantará ([he] will sing). However, the main function of Romance stress appears to be a clue for speech segmentation — namely to help the listener identify the word boundaries in normal speech, where inter-word spaces are usually absent.

The position of the stressed syllable in a word generally varies from word to word in each Romance language. Stress usually remains fixed on its assigned syllable within any language, however, even as the word is inflected. It is usually restricted to one of the last three syllables in the word, although Italian verb forms can violate this (e.g. teléfonano 'they telephone'). The limit may be exceeded also by verbs with attached clitics, provided the clitics are counted as part of the word; e.g. Spanish entregándomelo [en.tre.ˈɣan.do.me.lo] (delivering it to me), Italian mettiamocene [me.ˈtːjaː.mo.ʧe.ne] (let's put some of it in there), or Portuguese dávamo-vo-lo [ˈda.vɐ.mu.vu.lu] (we were giving it to you).

The Romance languages also share a number of features that were not the result of common inheritance, but rather of various cultural diffusion processes in the Middle Ages — such as literary diffusion, commercial and military interactions, political domination, influence of the Catholic Church, and (especially in later times) conscious attempts to "purify" them in accordance with Classical Latin. Some of those features have in fact spread to other non-Romance (and even non-Indo-European) languages, chiefly in Europe. Some of these "late origin" shared features are:

- Most Romance languages have polite forms of address that change the person and/or number of 2nd person subjects (T-V distinction), such as the tu/vous contrast in French, the tu/Ella (or more often Lei) contrast in Italian, the tu/dumneavoastră (from dominus + vostre, literally meaning "your Lordship") in Romanian or the tú (or vos) /usted contrast in Spanish. Italian also had another form (Voi) denoting more respect than a tu, but of a lesser degree than Ella; the use of Voi has been discontinued because it was strongly supported by fascists.

- They all have a large collection of learned hellenisms and latinisms, with prefixes, stems, and suffixes retained or reintroduced from Greek and Latin, and used to coin new words. Most of these are also used in English, e.g. tele-, poly-, meta-, pseudo-, dis-, ex-, post-, -scope, -logy, -tion, though their spelling may differ slightly; for example, poly- becomes poli- in Romanian, Italian and Spanish.

- During the Renaissance, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and a few other Romance languages developed a progressive aspect which did not exist in Latin. In French, progressive constructions remain very limited, the imperfect aspect generally being preferred, as in Latin.

- Many Romance languages now have a verbal construction analogous to the present perfect tense of English. In some, it has taken the place of the old preterite (at least in the vernacular); in others, the two coexist with somewhat different meanings (cf. English I did vs. I have done). A few examples:

- preterite only: Galician, Sicilian, Leonese, some dialects of Spanish;

- preterite and present perfect: Catalan, Occitan, Portuguese, standard Spanish;

- present perfect predominant, preterite now literary: French, Romanian, several dialects of Italian and Spanish.

- present perfect only: Romansh

Writing systems

The Romance languages have kept the writing system of Latin, adapting it to their evolution. One exception was Romanian before the 19th century, where, after the Roman retreat, literacy was reintroduced through the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet by Slavic influences. The Cyrillic alphabet was also used for Romanian (Moldovan) in the USSR. Also the non-Christian populations of Spain used the systems of their culture languages (Arabic and Hebrew) to write Romance languages such as Ladino and Mozarabic in aljamiado.

Letters

The Romance languages are written with the classical Latin alphabet of 22 letters — A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X, Y, Z — subsequently modified and augmented in various ways. In particular, the letters K and W are seldom used in most Romance languages, only for unassimilated foreign names and words.

While most of the 22 basic Latin letters have maintained their phonetic value, for some of them it has diverged considerably; and the new letters added since the Middle Ages have been put to different uses in different scripts. Some letters, notably H and Q, have been variously combined in digraphs or trigraphs (see below) to represent phonetic phenomena not recorded in Latin, or to get around previously established spelling conventions.

The spelling rules of most Romance languages are fairly simple, but subject to considerable regional variation. To a first approximation, the phonetic values of the letters can be summarized as follows:

- C: Generally a "hard" [k], but "soft" (fricative or affricate) before e, i, or y.

- G: Generally a "hard" [ɡ], but "soft" (fricative or affricate) before e, i, or y. In some languages, like Spanish, the hard g is pronounced as a fricative [ɣ] after vowels. In Romansch, the soft g is a voiced palatal plosive [ɟ] or a voiced alveolo-palatal affricate [dʑ].

- H: Silent in most languages; used to form various digraphs. But represents [h] in Romanian, Walloon and Gascon Occitan.

- J: Represents a fricative in most languages, or the palatal approximant [j] in Romansh and in several of the languages of Italy. Italian does not use this letter in native words. Usually pronounced like the soft g (except in Romansch and the languages of Italy).

- Q: As in Latin, its phonetic value is that of a hard c, and in native words it is always followed by a (sometimes silent) u. Romanian does not use this letter in native words.

- S: Generally voiceless [s], but voiced [z] between vowels in most languages. In Spanish, Romanian, Galician and several varieties of Italian, however, it is always pronounced voiceless. At the end of syllables, it may represent special allophonic pronunciations. In Romansh, it also stands for a voiceless or voiced fricative, [ʃ] or [ʒ], before certain consonants.

- W: No Romance language uses this letter in native words, with the exception of Walloon.

- X: Its pronunciation is rather variable, both between and within languages. In the Middle Ages, the languages of Iberia used this letter to denote the voiceless postalveolar fricative [ʃ], which is still the case in Modern Catalan and Portuguese. With the Renaissance the classical pronunciation [ks] — or similar consonant clusters, such as [ɡz], [ɡs], or [kθ] — were frequently reintroduced in latinisms and hellenisms. In Venetian it represents [z], and in Ligurian the voiced postalveolar fricative [ʒ]. Italian does not use this letter in native words.

- Y: This letter is not used in most languages, with the prominent exceptions of French and Spanish, where it represents [j] before vowels (or various similar fricatives such as the palatal fricative [ʝ], in Spanish), and the vowel or semivowel [i] elsewhere.

- Z: In most languages it represents the sound [z], but in Italian it denotes the affricates [ʣ] and [ʦ] (which, although not normally in contrast, are usually strictly assigned lexically in any single variety: Standard Italian gazza 'magpie' always with [ddz], mazza 'club, mace' only with [tts]), in Romansh the voiceless affricate [ʦ], and in Galician and Spanish it denotes either the voiceless dental fricative [θ] or [s].

Otherwise, letters that are not combined as digraphs generally have the same sounds as in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), whose design was, in fact, greatly influenced by the Romance spelling systems.

Digraphs and trigraphs

Since most Romance languages have more sounds than can be accommodated in the Roman Latin alphabet they all resort to the use of digraphs and trigraphs — combinations of two or three letters with a single sound value. The concept (but not the actual combinations) derives from Classical Latin; which used, for example, TH, PH, and CH when transliterating the Greek letters "θ", "ϕ" (later "φ"), and "χ" (These were once aspirated sounds in Greek before changing to corresponding fricatives and the <H> represented what sounded to the Romans like an /ʰ/ following /t/, /p/, and /k/ respectively. Some of the digraphs used in modern scripts are:

- CI: used in Italian, Romance languages in Italy and Romanian to represent /ʧ/ before A, O, or U.

- CH: used in Italian, Romance languages in Italy, Romanian, Romansh and Sardinian to represent /k/ before E or I; /ʧ/ in Occitan, Spanish, Leonese and Galician; [c] or [tɕ] in Romansh before A, O or U; and /ʃ/ in most other languages.

- DD: used in Sicilian and Sardinian to represent the voiced retroflex plosive /ɖ/. In recent history more accurately transcribed as DDH.

- DJ: used in Catalan and Walloon for /ʤ/.

- GI: used in Italian, Romance languages in Italy and Romanian to represent /ʤ/ before A, O, or U, and in Romansh to represent [ɟi] or /dʑi/ or (before A, E, O, and U) [ɟ] or /dʑ/

- GH: used in Italian, Romance languages in Italy, Romanian, Romansh and Sardinian to represent /ɡ/ before E or I, and in Galician for the voiceless pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ (not standard sound).

- GL: used in Romansh before consonants and I and at the end of words for /ʎ/.

- GLI: used in Italian and Romansh for /ʎ/.

- GN: used in French, Italian, Romance languages in Italy and Romansh for /ɲ/, as in champignon or gnocchi.

- GU: used before E or I to represent /ɡ/ or /ɣ/ in all Romance languages except Italian, Romance languages in Italy, Romansh, and Romanian (which use GH instead).

- IG: used at the end of word in Catalan for /ʧ/, as in maig, safareig or enmig.

- IX: used between vowels or at the end of word in Catalan for /ʃ/, as in caixa or calaix.

- LH: used in Portuguese and Occitan /ʎ/.

- LL: used in Spanish, Catalan, Galician, Leonese, Norman and Dgèrnésiais, originally for /ʎ/ which has merged in some cases with /j/. Represents /l/ in French unless it follows I (i) when it represents /j/ (or /ʎ/ in some dialects). It's used in Occitan for a long /ll/

- L·L: used in Catalan for a geminate consonant /ll/.

- NH: used in Portuguese and Occitan for /ɲ/, used in official Galician for /ŋ/ .

- N-: used in Piedmontese and Ligurian for /ŋ/ between two vowels.

- NN: used in Leonese for /ɲ/,

- NY: used in Catalan for /ɲ/.

- QU: represents [kw] in Italian, Romance languages in Italy, and Romansh; [k] in French and Spanish; [k] (before e or i) or [kw] (normally before a or o) in Occitan, Catalan and Portuguese.

- RR: used between vowels in several languages (Occitan, Catalan, Spanish...) to denote a trilled /r/ or a guttural R, instead of the flap /ɾ/.

- SC: used before E or I in Italian and Romance languages in Italy for /ʃ/, and in French and Spanish as /s/ in words of certain etymology.

- SCH: used in Romansh for [ʃ] or [ʒ].

- SCI: used in Italian and Romance languages in Italy to represent /ʃ/ before A, O, or U.

- SH: used in Aranese Occitan for /ʃ/.

- SS: used in French, Portuguese, Piedmontese, Romansh, Occitan, and Catalan for /s/ between vowels.

- TG: used in Romansh for [c] or [tɕ]. In Catalan is used for /ʤ/ between vowels, as in metge or fetge.

- TH: used in Jèrriais for /θ/; used in Aranese for either /t/ or /ʧ/.

- TJ: used between vowels and before A, O or U, in Catalan for /ʤ/, as in sotjar or mitjó.

- TSCH: used in Romansh for [ʧ].

- TX: used at the beginning or at the end of word or between vowels in Catalan for /ʧ/, as in txec, esquitx or atxa.

While the digraphs CH, PH, RH and TH were at one time used in many words of Greek origin, most languages have now replaced them with C/QU, F, R and T. Only French has kept these etymological spellings, which now represent /k/ or /ʃ/, /f/, /ʀ/ and /t/, respectively.

Double consonants

Gemination, in the languages where it occurs, is usually indicated by doubling the consonant, except when it does not contrast phonemically with the corresponding short consonant, in which case gemination is not indicated. In Jèrriais, long consonants are marked with an apostrophe: S'S is a long /zz/, SS'S is a long /ss/, and T'T is a long /tt/. The double consonants in French orthography, however, are merely etymological.

Diacritics and special characters

Romance languages use various diacritics, especially on vowels, to mark special pronunciations, or to distinguish between homophones, with the exception of Romanian. Romanian language does not use diacritics or accents, but it uses the special characters as distinct letters with distinct sounds, this way there is no need for constructions like sh, because of the usage of the characters ș for the sound [ʃ]. The Romanian distinct letters with their specific pronunciation are: ș: [ʃ], ț: [ts], ă: [ə], î and â: [ɨ], and these distinct letters are not diacritics.

The following are the most common use of diacritics in Romance languages.

- Palatalization: some historical palatalizations are indicated with the cedilla (ç) in French, Catalan, and Portuguese. In Spanish and several other world languages influenced by it, the grapheme ñ represents a palatal nasal consonant.

- Diaeresis: when a vowel and another letter that would normally be combined into a digraph with a single sound are exceptionally pronounced apart, this is often indicated with a diaeresis mark on the vowel. In the Spanish word pingüino (penguin), the letter u is pronounced, although normally it is silent in the digraph gu when this is followed by an e or an i. Other Romance languages that use the diaeresis in this fashion are French, Catalan, and (Brazilian) Portuguese.

- Homophones: words that are pronounced exactly or nearly the same way, but have different meanings, can be differentiated with an acute (as in Spanish, where si means "if" while sí means "yes", and Catalan, where os means "bone" and ós means "bear") or with a grave accent (French—in which ou means "or" and où means "where"—as well as Italian, Romansh—in which e means "and" and è means "is"—and Catalan—in which mà means "hand" and ma means the possessive adjective, feminine possessor "my"). The circumflex can also have this function in French, sometimes. Often, such words are monosyllables, the accented one being phonetically stressed, while the unaccented one is a clitic; examples are the Spanish clitics de, se, and te (a preposition and two personal pronouns), versus the stressed words dé, sé, and té (two verbs and a noun).

- Stress: the stressed vowel in a polysyllabic word may be indicated with the acute, é (in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan), or the grave accent, è (Italian, Catalan, Romansh). The orthographies of French and Romanian do not mark stress. In Italian and Romansh orthography, indicating stress with a diacritic is only required when it falls on the last syllable of a word.

- Vowel quality: the system of marking close-mid vowels with an acute, é, and open-mid vowels with a grave accent, è, is widely used (in Catalan, French, Italian, etc.) Portuguese, however, uses the circumflex (ê) for the former, and the acute (é), for the latter.

- Nasality: Portuguese marks nasal vowels with a tilde (ã) when they occur before other vowels. While not frequent among the other Romance languages, this orthographic convention has been adopted by several indigenous languages of the Americas, for instance the Guarani.

Less widespread diacritics in the Romance languages are the breve (in Romanian, ă) and the ring (in Wallon and the Bolognese dialect of Emiliano-Romagnolo, å). The French orthography includes the etymological ligatures œ and (more rarely) æ. The circumflex frequently has an etymological value in this language, as well; see Use of the circumflex in French, for further information.

Upper and lower case

Most languages are written with a mixture of two distinct but phonetically identical variants or "cases" of the alphabet: majuscule ("uppercase" or "capital letters"), derived from Roman stone-carved letter shapes, and minuscule ("lowercase"), derived from Carolingian writing and Medieval quill pen handwriting which were later adapted by printers in the 15th and 16th centuries.

In particular, all Romance languages presently capitalize (use uppercase for the first letter of) the following words: the first word of each complete sentence, most words in names of people, places, and organizations, and most words in titles of books. The Romance languages do not follow the German practice of capitalizing all nouns including common ones. Unlike English, the names of months (except in European Portuguese), days of the weeks, and derivatives of proper nouns are usually not capitalized: thus, in Italian one capitalizes Francia ("France") and Francesco ("Francis"), but not francese ("French") or francescano ("Franciscan"). However, each language has some exceptions to this general rule.

Vocabulary comparison

The table below provides a vocabulary comparison that illustrates a number of examples of sound shifts that have occurred between Latin and the main Romance languages, along with a selection of minority languages.

| English | Latin | Catalan | French | Galician | Italian | Norman Jèrriais | Sicilian | Venetian | Lombard (literary Milanese) | Piedmontese (West-Piedmont) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | [Mattiana] Mala; Pomum (fruit) | Poma | Pomme | Mazá / Pomo | Mela | Poumme | Pumu | Pomo | Pomm | Pom |

| Arm | Bracchium | Braç | Bras | Brazo | Braccio | Bras | Vrazzu | Bras | Brasc | Brass |

| Arrow | Sagitta; Frankish Fleuka | Fletxa / Sageta | Flèche | Frecha / Seta | Freccia / Saetta | Èrchelle | Sagghitta, Filecca/Frecia | Frecia | Frecia | Flecia |

| Bed | Lectus | Llit | Lit | Leito / Cama | Letto | Liet | Lettu, Ghiazzu | Lett / Branda | Lett | Let |

| Black | Niger; Ater | Negre | Noir | Negro / Atro | Nero | Nièr | Nìgghiru | Nero | Negher | Nèir |

| Book | Liber | Llibre | Livre / Bouquin | Libro | Libro | Livre | Lìbbiru | Libro | Liber | Lìber |

| Breast | Pectus | Pit | Poitrine | Peito | Petto | Estonma | Pettu | Pett /Peto | Stòmi | Stòmi |

| Cat | Feles; V.L. Cattus/Gattus[7] | Gat | Chat (kat, khat, cat) | Gato | Gatto | Cat | Gattu | Gatt /Gato | Gatt | Gat |

| Chair | Sella; Greek Kathedra | Cadira | Chaise | Cadeira | Sedia | Tchaîse | Segghia, Cadira | Carega | Cadrega | Cadrega / Carea |

| Cold (adj.) | Frigidus | Fred | Froid | Frío | Freddo | Fraid | Friddu | Fredo | Frecc | Frèid |

| Cow | Vacca | Vaca | Vache | Vaca | Vacca / Mucca[8] | Vaque | Vacca | Vaca | Vaca | Vaca |

| Day | Dies (adj. Diurnus) | Dia / Jorn | Jour | Día | Giorno / Dì | Jour | Dia, Ghiurnu | Dì | Dì | Di |

| Dead | Mortuus | Mort | Mort | Morto | Morto | Mort | Mortu | Mort | Mort | Mòrt |

| Die | Mori | Morir | Mourir | Morrer | Morire | Mouothi | Mòriri | Morir | Morì | Meuire/Murì |

| Family | Familia | Família | Famille | Familia | Famiglia | Famil'ye | Famigghia | Faméia | Familia | Famija |

| Finger | Digitus | Dit | Doigt | Dedo[9] | Dito | Dé | Ghìditu (for dìghitu) | Déo / Dièl | Did | Dil |

| Flower | Flos | Flor | Fleur | Flor | Fiore | Flieur | Hiuri | Fior | Fiôr | Fior |

| Give | Dare / Donare[10] | Donar | Donner | Dar | Dare | Donner / Bailli | Dunari | Dar | Dà | Dé |

| Go | Ire; Ambulare (to walk); V.L. Ambitare | Anar | Aller | Ir | Andare | Aller | Ghiri | Andar / Ndar | Andà | Andé |

| Gold | Aurum | Or | Or | Ouro | Oro | Or | Oru | Oro | Or | Òr |

| Hand | Manus | Mà | Main | Man | Mano | Main | Manu | Man | Man | Man |

| High | Altus | Alt | Haut | Alto | Alto | Haut | Autu | Alt | Alt | Àut |

| House | Domus; Casa (hut) | Casa | Maison[11] | Casa | Casa | Maîson[11] | Casa, Lurderi | Caxa / Cà | Cà | Ca |

| I | Ego | Jo | Je | Eu | Io | Eu | Mi | Mi | Mi / I | |

| Ink | Atramentum; Tincta (dye) | Tinta | Encre | Tinta[12] | Inchiostro | Encre | Tinta, Inca | Inciostro | Inciòster | Anciòst |

| January | Januarius | Gener | Janvier | Xaneiro | Gennaio | Janvyi | Ghinnaru | Genàr | Genar | Gené |

| Juice | Sucus | Suc | Jus | Zume | Succo | Jus | Sucu | Suk /Suco | Sugh | Gius / Bagna |

| Key | Clavis | Clau | Clé | Chave | Chiave | Clié | Chiavi | Ciave | Ciav | Ciav |

| Language | Lingua | Llengua | Langue | Lingua | Lingua | Langue | Lingua | Lengua | Lengua | Lenga |

| Man | Homo | Home | Homme | Home | Uomo | Houmme | Omu | Omm/Omo | Omm | Òmo / Òm |

| Moon | Luna | Lluna | Lune | Lúa | Luna | Leune | Luna | Luna | Luna | Lun-a |

| English | Latin | Catalan | French | Galician | Italian | Norman Jèrriais | Sicilian | Venetian | Lombard (literary Milanese) | Piedmontese (West-Piedmont) |

| Night | Nox | Nit | Nuit | Noite | Notte | Niet | Notti | Nott /Note | Nott | Neuit |

| Old | Vetus | Vell | Vieux[13] | Vello[14] | Vecchio | Vyi | Vecchiu | Véj /Vecio | Vècc | Vej |

| One | Unus | Un | Un | Un | Uno | Ieune | Unu | Un | Vun | Un |

| Pear | Pirum | Pera | Poire | Pera | Pera | Paithe | Piru | Péra | Per | Pruss |

| Play | Ludere; Jocare (to joke) | Jugar | Jouer | Xogar | Giocare | Jouer | Ghiucari | Xugàr | Giogà | Gieughe/Giughé |

| Ring | Anellus | Anell | Anneau | Anel | Anello | Anné / Bague | Aneddu | Anel / Aneło | Anèll | Anel |

| River | Flumen; Rivus (small river) | Riu | Rivière / Fleuve | Río[15] | Fiume | Riviéthe | Hiumi | Fiume / Rio | Fiumm | Fium / Ri |

| Sew | Consuere | Cosir | Coudre | Coser | Cucire | Couôtre | Cùsiri | Cuxir | Cusì | Cuse / Cusì |

| Snow | Nix | Neu | Neige | Neve | Neve | Né | Nivi, Prazza | Néve | Nev (verb:Fiocà) | Fiòca |

| Take | Capio; Prehendere (to seize) | Agafar / Prendre | Prendre | Prender[16] | Prendere | Prendre | Càpiri, Pigghiari | Tor /Tchor / Ciapàr | Ciapà / Toeu | Pijé |

| That | Ille; V.L. Eccu + Ille | Aquell | Quel | Aquel | Quello | Chu | Chiddu | Quel | Quèll | Col |

| The | Ille | el/la/lo els/les/los Balearic: es/sa/so ets/ses/sos[17] |

le/la les |

o/a os/as |

il/lo/la i/gli/le |

lé/la | lu, la, li | el/la i / le |

el/la i |

ël/la ij/le |

| Throw | Jacere; V.L. Lanceare (to throw a weapon); Adtirare | Llençar / Tirar | Lancer / Tirer | Lanzar / Guindar | Lanciare / Tirare | Pitchi | Ghiccari, Lanzari | Tiràr | Tirà/Trà[18] | Tiré/Campé |

| Thursday | dies Jovis | Dijous | Jeudi | Xoves | Giovedì | Jeudi | Ghiovi | Zioba / Jioba | Gioedì | Giòbia |

| Tree | Arbor | Arbre | Arbre | Árbore | Albero | Bouais | Àrvulu | Àlbaro | Pianta[19]/Alber | Pianta / Erbo |

| Two | Duo | Dos / Dues | Deux | Dous / Dúas | Due | Deux | Dui, Du | Dó /Du | Duu | Doi / Doe |

| Urn | Urna | Urna | Urne | Urna | Urna | ? | Vas | Urna | Urna | |

| Voice | Vox | Veu | Voix | Voz | Voce | Vouaix | Vuci | Voz | Vôs | Vos |

| Where | Ubi; Unde (where from) | On | Où | Onde / U | Dove | Ioù / Où'est | Unni | Ndó / Ndóe | Indoa | Andoa / Anté |

| White | Albus; Frankish Blank | Blanc[20] | Blanc[20] | Branco[21] / Alvo[22] | Bianco[23] | Blianc | Ghiancu | Biank | Bianch | Bianch |

| Who | Quis | Qui | Qui | Quen | Chi | Tchi | Cui | Chi / Ci | Chi | Chi |

| World | Mundus | Món | Monde | Mundo | Mondo | Monde | Munnu | Mond | Mond | Mond |

| Yellow | Flavus; Galbinus; Amarus (bitter) | Groc [24] | Jaune | Amarelo[25] | Giallo | Jaune | Ghiarnu | Gial | Giald | Giàun |

| English | Latin | Catalan | French | Galician | Italian | Norman Jèrriais | Sicilian | Venetian | Lombard (literary Milanese) | Piedmontese (West-Piedmont) |

| English | Latin | Occitan | Portuguese | Romanian | Romansh | Sardinian | Sicilian | Spanish | Walloon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | [Mattiana] Mala; Pomum (fruit) | Poma | Maçã / Pomo | Măr; Poamă (fruit) | Mela | Pumu | Manzana / Poma | Peme | |

| Arm | Bracchium | Braç | Braço | Braț | Bratsch | Bratzu | Vrazzu | Brazo | Bresse |

| Arrow | Sagitta; Frankish Fleuka | Sageta / Flècha | Seta / Flecha | Săgeată | Frizza | Fretza | Fileccia | Flecha / Saeta | Fletche |

| Bed | Lectus | Lièch (lièit) | Cama / Leito | Pat[26] | Letg | Lettu | Lettu | Cama / Lecho | Lét |

| Black | Niger; Ater | Negre | Preto[27] / Negro / Atro | Negru | Nair | Nieddu / Nigru | Nìguru / Nìuru | Negro / Prieto | Noer[28] |

| Book | Liber | Libre | Livro | Carte[29] | Cudesch[30] | Libru / Lìburu | Libbru | Libro | Live |

| Breast | Pectus | Pièch (pièit) | Peito | Piept | Pèz | Pettus | Pettu | Pecho | Sitoumak / Pwetrene |

| Cat | Feles; V.L. Cattus/Gattus[31] | Cat (gat, chat (kat, khat, cat)) | Gato | Pisică[32] | Giat | Gattu / Battu | Gattu / Jattu | Gato | Tchet |

| Chair | Sella; Cathedra | Cadièra (chadiera, chadèira) | Cadeira[33] | Scaun[34] | Sutga | Cadira / Cadrea | Seggia | Silla | Tcheyire |

| Cold (adj.) | Frigidus | Freg (freid, hred) | Frio | Frig | Fraid | Friu | Friddu | Frío | Froed |

| Cow | Vacca | Vaca (vacha) | Vaca | Vacă | Vatga | Bacca | Vacca | Vaca | Vatche |

| Day | Dies (adj. Diurnus) | Jorn / Dia | Dia | Zi | Di | Die | Jornu | Día | Djoû |

| Dead | Mortuus | Mòrt | Morto | Mort | Mort | Mortu / Mottu | Mortu | Muerto | Moirt[35] |

| Die | Mori | Morir | Morrer | (a) Muri | Murir | Morrer | Muriri / Mòriri | Morir | Mori |

| Family | Familia | Familha | Família | Familie[36] | Famiglia | Famìlia | Famigghia | Familia | Famile |

| Finger | Digitus | Det | Dedo[9] | Deget | Det | Didu | Jìditu | Dedo[9] | Doet[37] |

| Flower | Flos | Flor | Flor | Floare | Flur | Frore | (S)Ciuri / Hjuri | Flor | Fleur |

| Give | Dare / Donare[10] | Donar / Dar | Dar / Doar[10] | (a) Da | Dar | Dare | Dari / Dunari | Dar / Donar[10] | Diner |

| Go | Ire; Ambulare (to walk); V.L. Ambitare | Anar | Ir / Andar[38] | (a) Umbla / (a) Merge[39] | Ir | Andare | Jiri | Ir / Andar[38] | Aler |

| Gold | Aurum | Aur | Ouro, Oiro | Aur | Aur | Oru | Oru | Oro | Ôr |

| Hand | Manus | Man | Mão | Mână | Maun | Manu | Manu | Mano | Mwin |

| High | Altus | Aut / Naut | Alto[40] | Înalt | Aut | Artu / Attu | Àutu | Alto | Hôt |

| House | Domus; Casa (hut) | Ostal (ostau) / Maison / Casa | Casa | Casă | Chasa | Domu | Casa | Casa | Måjhon |

| I | Ego | Ieu / Jo | Eu | Eu | Jau | Deu | Iu / Jo / Ju / Eu / Jia | Yo | Dji |

| Ink | Atramentum; Tincta (dye) | Tencha (tinta) / Encra | Tinta[12] | Cerneală[41] | Tinta | Tinta | Inga[42] | Tinta | Intche |

| January | Januarius | Genièr (girvèir) | Janeiro | Ianuarie | Schaner | Ghennarzu / Bennarzu | Jinnaru | Enero | Djanvî |

| Juice | Sucus | Suc | Suco / Sumo | Suc | Suc | Sutzu | Sucu | Jugo / Zumo | Djus |

| Key | Clavis | Clau | Chave | Cheie | Clav | Crae | Chiavi / Ciavi | Llave / Clave | Sere |

| Language | Lingua | Lenga | Língua | Limbă | Lingua | Lingua | Lingua | Lengua | Lingaedje |

| Man | Homo | Òme | Homem[43] | Om[44] / Bărbat[45] | Um | Homine | Omu / Òminu | Hombre | Ome |

| Moon | Luna | Luna (lua) | Lua | Lună | Glina | Luna | Luna | Luna | Lune |

| English | Latin | Occitan | Portuguese | Romanian | Romansh | Sardinian | Sicilian | Spanish | Walloon |

| Night | Nox | Nuèch (nuèit) | Noite | Noapte | Notg | Notte | Notti | Noche | Nute / Nêt |

| Old | Vetus | Vièlh | Velho[14] / Vetusto[46] | Vechi[47] / Bătrân[48] | Vegl | Betzu / Sèneghe / Vedústus[46] | Vecchiu / Vecciu | Viejo | Vî |

| One | Unus | Un | Um | Unu | In | Unu | Unu | Un / Uno | Onk |

| Pear | Pirum | Pera | Pêra | Pară | Pair | Pira | Piru | Pera | Poere[49] |

| Play | Ludere; Jocare (to joke) | Jogar (jugar, joar) | Jogar | (a se) Juca | Giugar | Zogare | Jucari | Jugar | Djouwer |

| Ring | Anellus | Anèl (anèth, anèu) | Anel | Inel | Anè | Aneddu | Aneddu | Anillo | Anea[50] |

| River | Flumen; Rivus (small river) | Riu / Flume | Rio[15] / Flúvio | Fluviu; Râu[51]/ Rîu[52] | Flum | Riu / Frùmine | (S)Ciumi / Hjumi | Río | Rivire / Aiwe |

| Sew | Consuere | Cóser | Coser | (a) Coase | Cuser | Cosire | Cùsiri | Coser | Keude |

| Snow | Nix | Nèu | Neve | Nea / Zăpadă[53] | Naiv | Nie | Nivi | Nieve | Nive |

| Take | Capio; Prehendere (to seize) | Prene / Pilhar[54] | Prender[16] / Pegar / Levar[55]/ Tomar | (a) Prinde[56] / Lua[55] | Prender | Pigare[57] | Pigghiari[54] | Tomar / Prender[16] / Llevar[55] | Prinde |

| That | Ille; V.L. Eccu + Ille | Aquel (aqueth, aqueu) | Aquele | Acel/Acela | Quel | Kudhu / Kussu[58] | Chiddu / Chissu[58] | Aquel | Ké |

| The | Ille | lo/la los/las (lei[s], lu/li) |

o/a os/as |

-ul/-a -i/-le |

il/la ils/las |

su/sa sos/sas (is)[17] |

lu ('u) / la ('a) li ('i) |

el/la/lo los/las |

Li / Les |

| Throw | Jacere; V.L. Lanceare (to throw a weapon); Adtirare | Lançar | Lançar / Atirar / Deitar | (a) Arunca[59] | Trair[60] | Ghettare / Bettare | Lanzari / Jittari | Lanzar / Tirar / Echar | Tiper / Saetchî |

| Thursday | dies Jovis | Dijòus (dijaus) | Quinta-feira[61] | Joi | Gievgia | Zobia | Jovi / Juvidìa | Jueves | Djudi |

| Tree | Arbor | Arbre (aubre) | Árvore | Arbore / Pom[62]/ Copac[63] | Planta | Àrvore | Àrvuru | Árbol | Åbe |

| Two | Duo | Dos / Doas (dus, duas) | Dois[64] / Duas | Doi | Dua | Duos, Duas | Dui | Dos | Deus |

| Urn | Urna | Urna | Urna | Urnă | Urna | Urna | Urna | Urna | Djusse |

| Voice | Vox | Votz | Voz | Voce, Glas[65] | Vusch | Boghe | Vuci | Voz | Vwès |

| Where | Ubi; Unde (where from) | Ont (dont) | Onde[66] | Unde | Nua | Ue/Aundi | Unni | Donde[67] | Ewou / Wice / Dou |

| White | Albus (Frankish Blank) | Blanc[20] | Branco[21] / Alvo[22] | Alb[68] | Alv | Àbru | Biancu / Vrancu / Jancu | Blanco[69] | Blanc[20] |

| Who | Quis | Qual (quau), Qui, Cu | Quem | Cine | Tgi | Kini/Ki/Chie | Cui (cu') | Quien | Kî |

| World | Mundus | Mond | Mundo | Lume[70] | Mund | Mundu | Munnu | Mundo | Monde |

| Yellow | Flavus; Galbinus; Amarus (bitter) | Jaune | Amarelo[25][71] | Galben | Mellen | Grogu | Giarnu[72] | Amarillo[25] | Djaene[73] |

| English | Latin | Occitan | Portuguese | Romanian | Romansh | Sardinian | Sicilian | Spanish | Walloon |

See also

- List of Romance languages

- Interlingua

- Latin America

- Latin Europe

- Latin (demonym)

- Latin Union

- Romance copula

- Romance verbs

- Subjunctive

- Vulgar Latin

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes

- ↑ Ilari, Rodolfo (2002). Lingüística Românica. Ática. pp. 50. ISBN 85-08-04250-7.

- ↑ 1993 Statistical Abstract of Israel reports 250,000 speakers of Romanian in Israel, while the 1995 census puts the total figure of the Israeli population at 5,548,523

- ↑ Reports of about 300,000 Jews who left the country after WW2

- ↑ Source: MSN Encarta - Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People (number of Romance speakers estimated at 690 million speakers, number of Catalan language speakers estimated at 9.1 million)

- ↑ Modern Latin

- ↑ except for non-standard varieties that treat disjunctive pronouns as arguments and clitic pronouns as agreement markers (Henri Wittmann. "Le français de Paris dans le français des Amériques." Proceedings of the International Congress of Linguists 16.0416 (Paris, 20-25 juillet 1997). Oxford: Pergamon (CD edition). [1])

- ↑ unknown origin

- ↑ from either muggire (to moo) or, more likely, mungere (to milk)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 also poet. digito

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 meaning "to donate"

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 <mansio

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 also "atramento" (black ink)

- ↑ <diminutive vetulus

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 arch. also vedro

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 arch. also frume

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 meaning "to arrest", "to catch", or "to hold"

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 <ipsu/ipsa

- ↑ <trahere

- ↑ <planta

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 blanc (white, blank; Caucasian)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 branco (white, blank; Caucasian)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 literary alvo (white, fair; target, aim, goal)

- ↑ bianco (white, blank; Caucasian)

- ↑ from latin crocus (saffron)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 <dim. amarellus

- ↑ <Greek πάτος

- ↑ <appectoratum / V. Lat. prettu/pressu

- ↑ Nwêr or neûr

- ↑ <carta

- ↑ <codex

- ↑ unknown origin

- ↑ onomatopoeic

- ↑ also sela (saddle)

- ↑ <scamnum

- ↑ Mwârt or mwêrt

- ↑ Initially femeie; the meaning of the word shifted to "woman". Later, the word familie was reintroduced from Latin.

- ↑ Dwèt or Deut

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 meaning "to walk"

- ↑ <mergere

- ↑ arch. outo

- ↑ from Slavic *črъniti

- ↑ Old Fr. enque

- ↑ arch. home

- ↑ human being (generic meaning), also human male (rarely)

- ↑ human male, <barbatus "bearded (man)"

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 <Lat. vetustus

- ↑ objects, temporal

- ↑ people, <veteranus

- ↑ Pwêre or Peûre

- ↑ Ania or anê

- ↑ according to the 1993 orthographic rules

- ↑ according to the 1953 orthographic rules

- ↑ from Slavic *zapadati

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 <Lat. pilare / *pileare

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 <levare

- ↑ to catch/grip/grasp

- ↑ <captiare

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 <Lat. eccu + istud

- ↑ <eruncare

- ↑ <trahere "pull"

- ↑ <Lat. quinta feria (numerical)

- ↑ from poamă, "fruit" (<poma)

- ↑ part of the Eastern Romance substratum

- ↑ arch. dous

- ↑ from Slavic *gols

- ↑ arch. also u

- ↑ <de + onde; arch. also onde

- ↑ alb (white, blank; Caucasian)

- ↑ also target/goal/Caucasian

- ↑ <lumen

- ↑ also flavo/flávio from flavus/flavius and fulvo/fúlvio from fulvus/fulvius

- ↑ Old Norm. jauln or Old Fr. jalne

- ↑ Djane or djène