Roman Kingdom

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Roman Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Romanum) was the monarchical government of the city of Rome and its territories. Little is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom, as no written records from that time survive, and the histories about it were written during the Republic and Empire and are largely based on legend. However, the history of the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding, traditionally dated to 753 BC, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic in about 509 BC.

Contents |

Birth of Rome

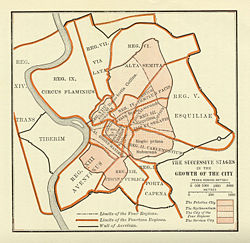

What eventually became the Roman Empire began as settlements around the Palatine Hill along the river Tiber in Central Italy. The river was navigable up to that place. The site also had a ford where the Tiber could be crossed. The Palatine Hill and hills surrounding it presented easily defensible positions in the wide fertile plain surrounding them. All these features contributed to the success of the city.

The traditional account of Roman history, which has come down to us through Livy, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus and others, is that in Rome's first centuries, it was ruled by a succession of seven kings. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro, allots 243 years for their reigns, an extraordinary average of almost 35 years (much longer than any historically documented dynasty), which, since the work of Barthold Georg Niebuhr, has been generally discounted by modern scholarship. The Gauls destroyed all of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia in 390 BC (Varronian, according to Polybius the battle occurred in 387/6), so no contemporary records of the kingdom exist, and all accounts of the kings must be carefully questioned.[1] Archaeological evidence does, however, support that a settlement was founded in Rome around the middle of the 8th century BC.

Political institutions

| Ancient Rome | |||

This article is part of the series: |

|||

|

|

|||

| Periods | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Kingdom 753 BC – 509 BC Roman Republic

|

|||

| Roman Constitution | |||

| Constitution of the Kingdom Constitution of the Republic |

|||

| Ordinary Magistrates | |||

|

|||

| Extraordinary Magistrates | |||

|

|||

| Titles and Honours | |||

Emperor

|

|||

| Precedent and Law | |||

|

|||

|

Other countries · Atlas |

King

Early Rome was a monarchy governed by kings (Latin rex). The kings, excluding the legendary Romulus who held office by virtue of being the city's founder, were all elected by the people of Rome to serve for life, with none of the kings relying on military force to gain the throne. Though no reference is made to the hereditary principle in the election of the first four kings, beginning with the fifth king Tarquinius Priscus, the royal inheritance flowed through the royal females of the deceased king. Consequently, the ancient historians state that the king was chosen on account of his virtues and not his descent.

The historians of ancient Rome make it difficult to determine the powers of the king as they referred to the king with the powers of their republican counterparts (namely the consuls). Some modern writers believe that the supreme power of Rome resided in the hands of the people and that the king was just the chief executive for the Senate and people while others believe that the king possessed the sovereign powers and that the Senate and people had only minor checks upon his powers.

The insignia of the kings of Rome were twelve lictors wielding the fasces bearing axes, the right to sit upon a Curule chair, the purple Toga Picta, red shoes, and a white diadem around the head. Of all these insignia, the most important was the purple toga.

Assuming the likelihood that the king was a sovereign in the traditional sense, the supreme power of the state would have been vested in the Rex, whose position would have made him the:

- Chief Executive – served as the head of government with the power to enforce the laws, managed all state owned property, disposed of conquered territory, and oversaw all public works

- Commander in Chief – commander of the Roman military with the sole power to levy and organize the legions, to appoint military leaders, and to conduct war

- Head of State – served as the chief representative of Rome in its relations with foreign powers and received all foreign ambassadors

- Chief Priest – served as official representative of Rome and its people before the gods with the power of general administrative control over Roman religion

- Chief Legislator – formulated and proposed legislative proposals as he deemed necessary

- Chief Judge – adjudicated all civil and criminal cases

Chief Executive

The king would have been invested with the supreme military, executive, and judicial authority through the use of imperium. The imperium of the king was held for life and protected him from ever being brought to trial for his actions. As being the sole owner of imperium in Rome at the time, the king possessed ultimate executive power and unchecked military authority as the commander-in-chief of all Rome's legions. Also, the laws that kept citizens safe from the misuse of magistrates owning imperium did not exist during the times of the king.

Another power of the king was the power to either appoint or nominate all officials to offices. The king would appoint a tribunus celerum to serve as both the tribune of Ramnes tribe in Rome but also as the commander of the king's personal bodyguard, the Celeres. The king was required to appoint the tribune upon entering office and the tribune left office upon the king's death. The tribune was second in rank to the king and also possessed the power to convene the Curiate Assembly and lay legislation before it.

Another officer appointed by the king was the praefectus urbi, which acted as the warden of the city. When the king was absent from the city, the prefect held all of the king's powers and abilities, even to the point of being bestowed with imperium while inside the city. The king even received the right to be the sole person to appoint patricians to the Senate.

Chief Priest

What is known for certain is that the king alone possessed the right to the auspice on behalf of Rome as its chief augur, and no public business could be performed without the will of the gods made known through auspices. The people knew the king as a mediator between them and the gods and thus viewed the king with religious awe. This made the king the head of the national religion and its chief executive. Having the power to control the Roman calendar, he conducted all religious ceremonies and appointed lower religious offices and officers. It is said that Romulus himself instituted the augurs and who was believed to have been the best augur of all. Likewise, King Numa Pompilius instituted the pontiffs and through them developed the foundations of the religious dogma of Rome.

Chief Legislator

Under the kings, the Senate and Curiate Assembly had very little power and authority; they were not independent bodies in that they didn't possess the right to meet together and discuss questions of state at their own will. They could only be called together by the king and could only discuss the matters the king laid before them. While the Curiate Assembly did have the power to pass laws that had been submitted by the king, the Senate was effectively an honorable council. It could advise the king on his action but by no means could prevent him from acting. The only thing that the king could not do without the approval of the Senate and Curiate Assembly was to declare war against a foreign nation.

Chief Judge

The king's imperium granted him both military powers as well as qualified him to pronounce legal judgment in all cases as the chief justice of Rome. Though he could assign pontiffs to act as minor judges in some cases, he had supreme authority in all cases brought before him, both civil and criminal. This made the king supreme in times of both war and peace. While some writers believed there was no appeal from the king's decisions, others believed that a proposal for appeal could be brought before the king by any patrician during a meeting of the Curiate Assembly.

To assist the king, a council advised the king during all trials, but this council had no power to control the king's decisions. Also, two criminal detectives (Quaestores Parridici) were appointed by him as well as a two man criminal court (Duumviri Perduellionis) which oversaw for cases of treason.

Senate

Romulus established the Senate after he founded Rome by hand selecting the most noble men (those of wealth and legitimate wives and children) to serve as a council for the city. As such, the Senate was the King’s advisory council as the Council of State. The Senate was composed of 300 Senators, with 100 Senators representing each of the three ancient tribes of Rome: the Ramnes (Latins), Tities (Sabines), and Luceres (Etruscans) tribes. Within each tribe, a Senator was selected from each of the tribe's ten curiae. The king had the sole authority to appoint the Senators, but this selection was done in accordance with ancient custom.

Under the monarchy, the Senate possessed very little power and authority as the king held most of the political power of the state and could exercise those powers without the Senate's consent. The chief function of the Senate was to serve as the king’s council and be his legislative coordinator. Once legislation proposed by the king passed the Comitia Curiata, the Senate could either veto it or accept it as law. The king was, by custom, to seek the advice of the Senate on major issues. However, it was left to him to decide what issues, if any, before them and he was free to accept or reject their advice as he saw fit. Only the king possessed the power to convene the Senate, except during the interregnum, during which the Senate possessed the authority to convene itself.

Election of the kings

Whenever a king died, Rome entered a period of interregnum. Supreme power of the state would devolve to the Senate, which was responsible for finding a new king. The Senate would assemble and appoint one of its own members—the interrex—to serve for a period of five days with the sole purpose of nominating the next king of Rome. After the five-day period, the interrex would appoint (with the Senate's consent) another Senator for another five-day term. This process would continue until a new king was elected. Once the interrex found a suitable nominee to the kingship, he would bring the nominee before the Senate and the Senate would review him. If the Senate passed the nominee, the interrex would convene the Curiate Assembly and preside as its president during the election of the King.

Once proposed to the Curiate Assembly, the people of Rome could either accept or reject him. If accepted, the king-elect did not immediately enter office. Two other acts still had to take place before he was invested with the full regal authority and power. First, it was necessary to obtain the divine will of the gods respecting his appointment by means of the auspices, since the king would serve as high priest of Rome. This ceremony was performed by an augur, who conducted the king-elect to the citadel where he was placed on a stone seat as the people waited below. If found worthy of the kingship, the augur announced that the gods had given favorable tokens, thus confirming the king’s priestly character.

The second act which had to be performed was the conference of the imperium upon the king. The Curiate Assembly’s previous vote only determined who was to be king, and had not by that act bestowed the necessary power of the king upon him. Accordingly, the king himself proposed to the Curiate Assembly a law granting him imperium, and the Curiate Assembly by voting in favor of the law would grant it.

In theory, the people of Rome elected their leader, but the Senate had most of the control over the process.

Comitia Curiata

The Comitia Curiata (Curiate Assembly) was the only legislative body under the monarchy. The Assembly contained all the Patricians and was subdivided into 30 curiae, with 10 curiae for each of the Ramnes, Tities, and Luceres tribes.[2] Composition of the curiae consisted of those gens that shared a common bond. All members of a curiae were allowed to vote. The majority of the votes within the curiae determined the curiae’s overall vote. A majority of the curiae determined the view of the entire Assembly.

As was with the case of the Senate, the Assembly possessed little power and was not an independent body. The Assembly could be called together only by the Rex or the Interrex. However, stated meeting, on the first day of the month (kalends) and the end of the first week of the month (nones), were in place to hear announcements in reflecting the calendar. Only the Rex or Interrex could propose measures to be placed before the Assembly and no debate on the issue was allowed; only an up or down vote of the proposal. Propositions of the Rex or a declaration of war were the only issues voted on by the Assembly. Most propositions that the Rex was required to seek the approval of the Assembly on dealt with the affairs and organization of the gens.

Legendary kings of Rome

Reign of Romulus

Romulus was not only Rome's first king but also the city's founder. In 753 B.C., Romulus began building the city upon the Palatine Hill. After founding Rome, he invited criminals, runaway slaves, exiles, and other undesirables by granting them asylum. In this manner, Romulus populated five of the seven hills of Rome. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighboring Sabine tribe to a festival where he abducted the Sabine women and brought them back to Rome (remembered as The Rape of the Sabine Women). After the ensuing war with the Sabines, Romulus brought the Sabines and Romans under the diarchy of himself and Titus Tatius.

Romulus divided the people of Rome between the able bodied men and those unfit for combat. The fighting men became the Roman legions consisting of 6,000 infantry and 600 cavalry. The rest became the people of Rome and out of these people, Romulus selected 100 of the most noble men to serve as senators in an advisory council for the king, the Roman Senate. These men he called patres, and their descendants became the republican nobles and elite, the patricians. With the union between the Romans and Sabines, Romulus added another 100 members to the Senate of Sabine birth.

Under Romulus, the augurs became an official part of the Roman religion[3] and the Comitia Curiata was instituted. To form the basis of the Comitia Curiata, Romulus divided the people of Rome into three tribes: one for Romans (ramnes), a second for Sabines (tities), and a third for all others (luceres). Each tribe elected ten representatives, known as curiae, to form a single voting body.[4] Romulus would convene the Curiate and lay proposals from either himself or the Senate before the Curiate for ratification. All proposals passed before the Comitia Curiata were either unanimously supported or unanimously defeated as the majority of curiate voting was viewed as the opinion of the entire Curiate.

After 38 years as king of Rome, Romulus had fought in several successful wars, expanding the control of Rome over all of Latium and many of the surrounding areas. Romulus would be remembered as early Rome's greatest conqueror and as one of the men with the most pietas in Roman history. After his death at the age of 54, Romulus was deified as the war god Quirinus and served not only as one of the three major gods of Rome but also as the deified likeness of the city of Rome.

Reign of Numa Pompilius

According to Early History of Rome by Livy, Numa first gained reputation as a man of justice, and after Romulus' strange and mysterious death, the kingship fell to Numa Pompilius.[3] Aside for his reputation for justice, Numa was probably chosen in attempt to make amends with the people of Sabine.

Though first unwilling to serve as king, his father convinced him to take up the position as a service to the gods. Celebrated for his natural wisdom, Numa’s reign was marked by peace and prosperity.

Numa reformed the Roman calendar by adjusting it for the solar and lunar year as well as by adding the months of January and February to bring the total number of months to twelve.[5] Numa instituted several of Rome's religious rituals including the Salii, and a flamen maioris to serve as the chief priest to Quirinus, the Flamen Quirinalis. [6] Numa organized the area in and around Rome into districts for easier management. He is also credited with the organization of Rome’s first occupational guilds.

Numa is remembered as the most religious of the kings (surpassing even Romulus), and during his reign, he introduced the flamens, the vestal virgins of Rome, the pontiffs and the College of Pontiffs. Under his administration, temples to Vesta and Janus were constructed. Also during his reign, it was said that a shield from Jupiter fell from the sky with the fate of Rome written on it.[6] Numa ordered eleven copies of the shield to be created and these shields became sacred to the Romans.

As a peace-loving and gentle man, Numa planted ideas of meekness and justice within the minds of the Romans. The doors to the Temple of Janus were never open a single day as Numa waged no wars during his reign. After 43 years of rule, Numa died a peaceful and natural death.

Reign of Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius was much like Romulus in his warlike behavior and completely unlike Numa in his lack of respect for the gods. Tullus waged war against Alba Longa, Fidenae, and Veii, thus granting Rome even greater territory and power. It was during Tullus' reign that the city of Alba Longa was completely destroyed and Tullus enslaved the population, sending it back to Rome.

Tullus desired war so much that he even waged another war against the Sabines. It has been said, that Tullus' reign marked the Roman people's growing lust for conquest at the expense of peace. Tullus fought so many wars that he completely neglected the worship of the god and legend has it, that because of these wars, a plague infected the city, and Tullus himself fell ill. When Tullus called upon Jupiter and begged assistance, Jupiter responded with a bolt of lightning that burned the king and his house to ashes.

Despite his war-like nature, Tullus Hostilius selected and represented the third group of people to make up Rome’s patrician class consisting of those who had come to Rome seeking asylum and a new life. He also constructed a new home for the Senate, the Curia, which survived for over 500 years after his death. His reign lasted for 31 years.

Reign of Ancus Marcius

Following mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa’s grandson, Ancus Marcius. Much like his grandfather, Ancus did little to expand the borders of Rome and only fought war when his territories needed defending. He also built Rome's first prison on the Capitoline Hill.

During his reign, Janiculum Hill on the western bank was fortified to further protect Rome, and the first bridge across the Tiber River was built. He also founded the port of Ostia on the Tyrrhenian Sea and established Rome’s first salt works. Rome's size increased as Ancus used diplomacy to peacefully join some of the smaller surrounding cities into alliance with Rome. In this manner, he completed the conquest of the Latins and relocated them to the Aventine Hill, thus forming the plebeian class of Romans.

He died a natural death, like his grandfather before him, after 25 years as king, marking the end of the Latin-Sabine kings of Rome.

Reign of Tarquinius Priscus

Tarquinius Priscus was the fifth king of Rome and the first of Etruscan birth (through Greek ancestry). After emigrating to Rome, he gained favor with Ancus, who later adopted him as his son. Upon ascending the throne, he waged wars against the Sabines and Etruscans, doubling the size of Rome and brought great treasures to the city.

One of his first reforms was to add 100 new members to the Senate from the conquered Etruscan tribes, bringing the total number of senators to 300. He used the treasures Rome had acquired from the conquests to build great monuments for Rome. Among these were Rome’s great sewer systems, the Cloaca Maxima, which he used to drain the swamp-like area between the Seven Hills of Rome. In the its place, he began construction on the Roman Forum. He also founded the Roman games.

The most famous of his great building projects is the Circus Maximus, a giant stadium used for chariot races. Priscus followed up the Circus Maximus with the construction of the temple-fortress to the god Jupiter upon the Capitoline Hill. Unfortunately, he was killed after 38 years as king at the hands of on of one of Ancus Marcius' sons before it could be completed. His reign is best remembered for introducing the Roman symbols of military and civil offices as well as the introduction of the Roman Triumph, being the first Roman to celebrate one.

Reign of Servius Tullius

Following Priscus’s death, his son-in-law Servius Tullius succeeded him to the throne, the second king of Etruscan birth to rule Rome. Like his father-in-law before him, Servius fought successful wars against the Etruscans. He used the booty from the campaigns to build the first walls to fully encircle the Seven Hills of Rome, the pomerium. He also made organizational changes to the Roman army.

He was renowned for implementing a new constitution for the Romans, further developing the citizen classes. He instituted the world’s first census which divided the people of Rome into five economic classes, and formed the Century Assembly. He also used his census to divide the people within Rome into four urban tribes based upon location within the city, establishing the Tribal Assembly. He also oversaw the construction of the temple to Diana on the Aventine Hill.

Servius’ reforms brought about a major change in Roman life: voting rights were now based on socio-economic status, transferring much of the power into the hands of the Roman elite. However, as time passed, Servius increasingly favored the poor in order to obtain support among the plebs. His appeal to the plebs often resulted in legislation unfavorable to the patricians. The 44-year reign of Servius came to an abrupt end when he was assassinated in a conspiracy led by his own daughter, Tullia, and her husband, Tarquinus Superbus.

Reign of Tarquinius Superbus

The seventh and final king of Rome was Tarquinius Superbus. As the son of Priscus and the son-in-law of Servius, Tarquinius was also of Etruscan birth. It was also during his reign that the Etruscans reached their apex of power. More than other kings before him, Tarquinius used violence, murder, and terrorism to maintain control over Rome. He repealed many of the earlier constitutional reforms set down by his predecessors.

Tarquinius removed and destroyed all the Sabine shrines and altars from the Tarpeian Rock, enraging the people of Rome. A sex scandal brought down the king. Allegedly, Tarquinius allowed his son, Sextus Tarquinius, to rape Lucretia, a patrician Roman. Sextus had threatened Lucretia that if she refused to copulate with him, he would kill a slave, then kill her, and have the bodies discovered together, thus creating a gigantic conspiracy. Lucretia then told her relatives about the threat, and subsequently committed suicide to avoid any such conspiracy. Lucretia’s kinsman, Lucius Junius Brutus (ancestor to Marcus Brutus), summoned the Senate and had Tarquinius and the monarchy expelled from Rome in 510 BC.

Etruscan rule in Rome, according to tradition, then came to a dramatic end in 510 BC, with the expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus, which also signaled the downfall of Etruscan power in Latium, the gradual cessation of Etruscan influences at Rome, and the establishment of a Republican constitution.[7]

Many years later during the Republican period, this strong Roman opposition to kings was used by the Senate as a rationalization for the murder of the agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus. Lucius Junius Brutus and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, a member of the Tarquin family and Lucretia's widower, went on to become one of the first consuls of Rome’s new government. This new government would lead the Romans to conquer most of the Mediterranean world and would survive for the next 500 years until the rise of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus. Even then, the trappings of the Republic were not entirely done away with; the Republic would survive in a debased form until the Dominate.

Public offices after the monarchy

To replace the leadership of the kings, a new office was created with the title of consul. Initially, the consuls possessed all of the king’s powers in the form of two men, elected for a one-year term, who could veto each other’s actions. Later, the consuls’ powers were broken down further by adding other magistrates that each held a small portion of the king’s original powers. First among these was the praetor, which removed the Consuls’s judicial authority from them. Next came the censor, which stripped from the consuls the power to conduct the census.

The Romans instituted the idea of a dictatorship. A dictator would have complete authority over civil and military matters within the Roman Empire and therefore was unquestionable. However, the power of the dictator was so absolute that Ancient Romans were hesitant in electing one, reserving this decision only to times of severe emergencies. Although this seems similar to the roles of a king, dictators of Rome were limited to serving a maximum six-month term limit. Contrary to the modern notion of a dictator as an usurper, Roman Dictators were chosen willfully, usually from the ranks of consuls, during turbulent periods when one-man rule proved more efficient.

The king's religious powers were given to two new offices: the Rex Sacrorum and the Pontifex Maximus. The Rex Sacrorum was the de jure highest religious official for the Republic. His sole task was to make the annual sacrifice to Jupiter, a privilege that had been previously reserved for the king. The pontifex maximus, however, was the de facto highest religious official, who held most of the king’s religious authority. He had the power to appoint all vestal virgins, flamens, pontiffs, and even the Rex Sacrorum himself. By the beginning of the 1st Century BC, the Rex Sacrorum was all but forgotten and the pontifex maximus given almost complete religious authority over the Roman religion.

Return of the monarchical system

With the ascent of Gaius Julius Caesar and his adoptive son Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, the powers of the king almost returned. Gaius Julius Caesar was elected both pontifex maximus and dictator for life, which gave him even more powers than the ancient kings of old. He also affected red shoes, and had a diadem publicly placed on his head by Marcus Antonius, although he removed it to great applause. Caesar was assassinated on the "Ides of March", 44 BC. During the period between 28 BC and 12 BC, Augustus gained consular imperium and the powers of the Tribune of the People, combined with the positions of Pontifex Maximus and princeps senatus, making him a de facto monarch. This was the beginning of the Principate, although republican institutions continued until the Dominate. Even into the Byzantine era, the emperor would share the title of consul with another. There was also the papacy, which governed Rome for a period of time, along with the Papal States.

References

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac. Asimov's Chronology of the World. New York: HarperCollins, 1991. p. 69.

- ↑ Livy, The History of Rome 1.13

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Livy, The History of Rome 1.18

- ↑ Livy, The History of Rome 1.17

- ↑ Livy, The History of Rome 1.19

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Livy, The History of Rome 1.20

- ↑ Cary, M.; Scullard, H. H., A History of Rome. Page 55. 3rd Ed. 1979. ISBN 0312383959.

Bibliography

See also

- History of Rome

- Timeline of Ancient Rome

- Feral children in mythology and fiction

External links

- Patria Potestas: a view of suppressed matrilineality in the early legends of Rome

- The Kings of Rome

- Roman History

- [1]"Legendary Kings"

- Nova Roma - Educational Organization about "All Things Roman"

- Polish Portal of Ancient Rome

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||