Roe v. Wade

| Roe v. Wade | ||||||

|

||||||

| Argued December 9, 1971 Reargued October 11, 1972 Decided January 22, 1973 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full case name |

Jane Roe, et al. v. Henry Wade, District Attorney of Dallas County

|

|||||

| Citations | 410 U.S. 113 (more) 93 S. Ct. 705; 35 L. Ed. 2d 147; 1973 U.S. LEXIS 159 |

|||||

| Prior history | Judgment for plaintiffs, injunction denied, 314 F. Supp. 1217 (N.D. Tex. 1970); probable jurisdiction noted, 402 U.S. 941 (1971); set for reargument, 408 U.S. 919 (1972) | |||||

| Subsequent history | Rehearing denied, 410 U.S. 959 (1973) | |||||

| Argument | Oral argument | |||||

| Holding | ||||||

| Texas law making it a crime to assist a woman to get an abortion violated her due process rights. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas affirmed in part, reversed in part. | ||||||

| Court membership | ||||||

|

||||||

| Case opinions | ||||||

| Majority | Blackmun, joined by Burger, Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, Marshall, Powell | |||||

| Concurrence | Burger | |||||

| Concurrence | Douglas | |||||

| Concurrence | Stewart | |||||

| Dissent | White, joined by Rehnquist | |||||

| Dissent | Rehnquist | |||||

| Laws applied | ||||||

| U.S. Const. Amend. XIV; Tex. Code Crim. Proc. arts. 1191–94, 1196 | ||||||

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), is a United States Supreme Court case that resulted in a landmark decision regarding abortion.[1] According to the Roe decision, most laws against abortion in the United States violated a constitutional right to privacy under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision overturned all state and federal laws outlawing or restricting abortion that were inconsistent with its holdings. Roe v. Wade is one of the most controversial and politically significant cases in U.S. Supreme Court history. Its lesser-known companion case, Doe v. Bolton, was decided at the same time.[2]

Roe v. Wade centrally held that a mother may abort her pregnancy for any reason, up until the "point at which the fetus becomes ‘viable.’" The Court defined viable as being "potentially able to live outside the mother's womb, albeit with artificial aid. Viability is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks."[1] The Court also held that abortion after viability must be available when needed to protect a woman's health, which the Court defined broadly in the companion case of Doe v. Bolton. These rulings affected laws in 46 states.[3]

The Roe v. Wade decision prompted national debate that continues today. Debated subjects include whether and to what extent abortion should be legal, who should decide the legality of abortion, what methods the Supreme Court should use in constitutional adjudication, and what the role should be of religious and moral views in the political sphere. Roe v. Wade reshaped national politics, dividing much of the nation into pro-Roe (mostly pro-choice) and anti-Roe (mostly pro-life) camps, while activating grassroots movements on both sides.

Contents |

History of the case

In 1970, attorneys Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington filed suit in a U.S. District Court in Texas on behalf of Norma L. McCorvey ("Jane Roe"). McCorvey claimed her pregnancy was the result of rape.[4][5] The defendant in the case was Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade, representing the State of Texas.

The district court ruled in McCorvey's favor on the merits, but declined to grant an injunction against the enforcement of the laws barring abortion.[6] The district court's decision was based upon the Ninth Amendment, and the court also relied upon a concurring opinion by Justice Arthur Goldberg in the 1965 Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut, regarding a right to use contraceptives. Few state laws proscribed contraceptives in 1965 when the Griswold case was decided, whereas abortion was widely proscribed by state laws in the early 1970s.[7]

Roe v. Wade ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal. Following a first round of arguments, Justice Harry Blackmun drafted a preliminary opinion that emphasized what he saw as the Texas law's vagueness.[8] Justices William Rehnquist and Lewis F. Powell, Jr. joined the Supreme Court too late to hear the first round of arguments. Therefore, Chief Justice Warren Burger proposed that the case be reargued; this took place on October 11, 1972. Weddington continued to represent Roe, and Texas Assistant Attorney General Robert C. Flowers stepped in to replace Wade. Justice William O. Douglas threatened to write a dissent from the reargument order, but was coaxed out of the action by his colleagues, and his dissent was merely mentioned in the reargument order without further statement or opinion.[9]

Supreme Court decision

The court issued its decision on January 22, 1973, with a 7 to 2 majority voting to strike down Texas abortion laws. Burger and Douglas' concurring opinion and White's dissenting opinion were issued separately, in the companion case of Doe v. Bolton.

The Roe Court deemed abortion a fundamental right under the United States Constitution, thereby subjecting all laws attempting to restrict it to the standard of strict scrutiny. Although abortion is still considered a fundamental right, subsequent cases, notably Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Stenberg v. Carhart, and Gonzales v. Carhart have affected the legal standard.

The opinion of the Roe Court, written by Justice Harry Blackmun, declined to adopt the district court's Ninth Amendment rationale, and instead asserted that the "right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy." Douglas, in his concurring opinion from the companion case Doe v. Bolton, stated more emphatically that, "The Ninth Amendment obviously does not create federally enforceable rights." Thus, the Roe majority rested its opinion squarely on the Constitution's due process clause.

According to the Roe Court, "the restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a majority of States today are of relatively recent vintage." Abortion before Roe had been subject to criminal statutes since at least the nineteenth century.[10] Section VI of Blackmun's opinion was devoted to an analysis of historical attitudes, including those of the Persian Empire, Greek times, the Roman era, the Hippocratic oath, the common law, English statutory law, American law, the American Medical Association, the American Public Health Association, and the American Bar Association.

Without finding what it deemed a sufficient historical basis to justify the Texas statute, the Court identified three possible justifications in Section VII of the opinion to explain the criminalization of abortion: (1) women who can receive an abortion are more likely to engage in "illicit sexual conduct"; (2) the medical procedure was extremely risky prior to the development of antibiotics and, even with modern medical techniques, is still risky in late stages of pregnancy; and (3) the state has an interest in protecting prenatal life. To the first, Blackmun wrote that "no court or commentator has taken the argument seriously" and the statute failed to "distinguish between married and unwed mothers"; according to the Court, the second and third constitute valid state interests. In Section X, the Court reiterated, "[T]he State does have an important and legitimate interest in preserving and protecting the health of the pregnant woman ... and that it has still another important and legitimate interest in protecting the potentiality of human life."

Although the Constitution does not explicitly mention any right of privacy, the Court had previously found support for various privacy rights in several provisions of the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment, as well as in the "penumbra" of the Bill of Rights. But instead of relying upon the Bill of Rights or "penumbras, formed by emanations", as the Court had done in Griswold v. Connecticut, the Roe Court relied on a "right of privacy" that it said was located in the due process clause of the Constitution.

The Court determined that "arguments that Texas either has no valid interest at all in regulating the abortion decision, or no interest strong enough to support any limitation upon the woman's sole determination, are unpersuasive", and declared, "We, therefore, conclude that the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation."

When weighing the competing interests that the Court had identified, Blackmun also asserted that if the fetus was defined as a person for purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment then the fetus would have a specific right to life under that Amendment. The Court majority determined that the original intent of the Constitution (up to the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868) did not require protection of the unborn.

The Court's determination of whether a fetus can enjoy constitutional protection was separate from the notion of when life begins: "We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man's knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer." The Court only believed itself positioned to resolve the question of when a right to abortion exists.

The decision established a system of trimesters that attempted to balance the state's legitimate interests against the abortion right. The Court ruled that the state cannot restrict a woman's right to an abortion during the first trimester, the state can regulate the abortion procedure during the second trimester "in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health", and the state can choose to restrict or proscribe abortion as it sees fit during the third trimester when the fetus is viable ("except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother").

Justiciability

An aspect of the decision that attracted comparatively little attention was the Court's disposition of the issues of standing and mootness. The Supreme Court does not issue advisory opinions (those stating what the law would be in some hypothetical circumstance). Instead, there must be an actual case or controversy, including particularly a plaintiff who is aggrieved and seeks relief. In the Roe case, "Jane Roe", who began the litigation in March 1970, had already given birth by the time the case was argued before the Supreme Court in December 1971. By the traditional rules, therefore, there was an argument that Roe's appeal was moot because she would not be affected by the ruling, and also because she lacked standing to assert the rights of other pregnant women.[11]

The Court concluded that the case came within an established exception to the rule; one that allowed consideration of an issue that was "capable of repetition, yet evading review." This phrase had been coined in 1911 by Justice Joseph McKenna.[12] Blackmun's opinion quoted McKenna, and noted that pregnancy would normally conclude more quickly than an appellate process: "If that termination makes a case moot, pregnancy litigation seldom will survive much beyond the trial stage, and appellate review will be effectively denied."

Dissents

Associate Justices Byron R. White and William H. Rehnquist wrote emphatic dissenting opinions in this case. Justice White wrote:

| “ | I find nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the Court's judgment. The Court simply fashions and announces a new constitutional right for pregnant mothers and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invests that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes. The upshot is that the people and the legislatures of the 50 States are constitutionally disentitled to weigh the relative importance of the continued existence and development of the fetus, on the one hand, against a spectrum of possible impacts on the mother, on the other hand. As an exercise of raw judicial power, the Court perhaps has authority to do what it does today; but, in my view, its judgment is an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review that the Constitution extends to this Court.[2] | ” |

White asserted that the Court "values the convenience of the pregnant mother more than the continued existence and development of the life or potential life that she carries." Despite White suggesting he "might agree" with the Court's values and priorities, he wrote that he saw "no constitutional warrant for imposing such an order of priorities on the people and legislatures of the States." White criticized the Court for involving itself in this issue by creating "a constitutional barrier to state efforts to protect human life and by investing mothers and doctors with the constitutionally protected right to exterminate it." He would have left this issue, for the most part, "with the people and to the political processes the people have devised to govern their affairs."

Rehnquist elaborated upon several of White's points, by asserting that the Court's historical analysis was flawed:

| “ | To reach its result, the Court necessarily has had to find within the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment a right that was apparently completely unknown to the drafters of the Amendment. As early as 1821, the first state law dealing directly with abortion was enacted by the Connecticut Legislature. By the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, there were at least 36 laws enacted by state or territorial legislatures limiting abortion. While many States have amended or updated their laws, 21 of the laws on the books in 1868 remain in effect today.[1] | ” |

From this historical record, Rehnquist concluded that, "There apparently was no question concerning the validity of this provision or of any of the other state statutes when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted." Therefore, in his view, "the drafters did not intend to have the Fourteenth Amendment withdraw from the States the power to legislate with respect to this matter."

Controversy

Some pro-life supporters argue that all nine justices in Roe failed to adequately recognize that life begins at conception (sometimes referred to as "fertilization") and should therefore be protected by the Constitution;[13] the dissenting justices in Roe instead wrote that decisions about abortion "should be left with the people and to the political processes the people have devised to govern their affairs."[2] Other pro-life supporters argue that, in the absence of definite knowledge of when life begins, it is best to avoid the risk of doing harm.[14] Every year on the anniversary of the decision, tens of thousands of pro-life protesters demonstrate outside the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. in the March for Life.

Supporters of Roe describe it as vital to preservation of women's rights, personal freedom, and privacy. Denying the abortion right has been equated to compulsory motherhood, and some scholars (not including any member of the Supreme Court) have argued that abortion bans therefore violate the Thirteenth Amendment:

| “ | When women are compelled to carry and bear children, they are subjected to 'involuntary servitude' in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment….[E]ven if the woman has stipulated to have consented to the risk of pregnancy, that does not permit the state to force her to remain pregnant.[15] | ” |

Opponents of Roe have objected that the decision lacks a valid Constitutional foundation. Like the dissenters in Roe, they have maintained that the Constitution is silent on the issue, and that proper solutions to the question would best be found via state legislatures and the democratic process, rather than through an all-encompassing ruling from the Supreme Court. Supporters of Roe contend that the decision has a valid constitutional foundation, or contend that justification for the result in Roe could be found in the Constitution but not in the articles referenced in the decision.[15][16]

In response to Roe v. Wade, most states enacted or attempted to enact laws limiting or regulating abortion, such as laws requiring parental consent for minors to obtain abortions, parental notification laws, spousal mutual consent laws, spousal notification laws, laws requiring abortions to be performed in hospitals but not clinics, laws barring state funding for abortions, laws banning abortions utilizing intact dilation and extraction procedures (often referred to as partial-birth abortion), laws requiring waiting periods before abortion, or laws mandating women read certain types of literature before choosing an abortion.[17] Congress in 1976 passed the Hyde Amendment, barring federal funding of abortions for poor women through the Medicaid program. The Supreme Court struck down several state restrictions on abortions in a long series of cases stretching from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s, but upheld restrictions on funding, including the Hyde Amendment, in the case of Harris v. McRae (1980).[18]

The most prominent organized groups that mobilized in response to Roe are the National Abortion Rights Action League on the pro-choice side, and the National Right to Life Committee on the pro-life side. The late Harry Blackmun, author of the Roe opinion, was a determined advocate for the decision. Others have joined him in support of Roe, including Judith Jarvis Thomson, who before the decision had offered an influential defense of abortion.[19]

Roe remains controversial. Polls show continued division about its landmark rulings, and about the decision as a whole.

Internal memoranda

Internal Supreme Court memoranda surfaced in the Library of Congress in 1988, among the personal papers of Douglas and other Justices, showing the private discussions of the Justices on the case. Blackmun said of the majority decision he authored, "You will observe that I have concluded that the end of the first trimester is critical. This is arbitrary, but perhaps any other selected point, such as quickening or viability, is equally arbitrary."[20] Stewart said the lines were "legislative" and wanted more flexibility and consideration paid to the state legislatures, though he joined Blackmun's decision.[21]

The assertion that the Supreme Court was making a legislative decision is often repeated by opponents of the Court's decision.[22] The "viability" criterion, which Blackmun acknowledged was arbitrary, is still in effect, although the point of viability has changed as medical science has found ways to help premature babies survive.[23]

Critiques

Liberal and feminist legal scholars have had various reactions to Roe, not always giving the decision unqualified support. One reaction has been to argue that Justice Blackmun reached the correct result but went about it the wrong way.[24] Another reaction has been to argue that the ends achieved by Roe do not justify the means.[25]

William Saletan has written that "Blackmun’s [Supreme Court] papers vindicate every indictment of Roe: invention, overreach, arbitrariness, textual indifference."[26] In a 1973 article in the Yale Law Journal, Professor John Hart Ely criticized Roe as a decision which "is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be."[27] Ely added: "What is frightening about Roe is that this super-protected right is not inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers’ thinking respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they included, or the nation’s governmental structure."

Similarly, Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe has noted that, "One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found."[28] Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox wrote: "[Roe’s] failure to confront the issue in principled terms leaves the opinion to read like a set of hospital rules and regulations.... Neither historian, nor layman, nor lawyer will be persuaded that all the prescriptions of Justice Blackmun are part of the Constitution."[29]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg has criticized the Court's ruling in Roe v. Wade for terminating a nascent democratic movement to liberalize abortion law.[30] Likewise, legal affairs editor Jeffrey Rosen[31] and Michael Kinsley[32] say that a democratic movement would have been the correct way to build a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights.

Legal analyst Benjamin Wittes has written that Roe "disenfranchised millions of conservatives on an issue about which they care deeply".[33] Edward Lazarus, a former Blackmun clerk who "loved Roe’s author like a grandfather" wrote: "As a matter of constitutional interpretation and judicial method, Roe borders on the indefensible....Justice Blackmun’s opinion provides essentially no reasoning in support of its holding. And in the almost 30 years since Roe’s announcement, no one has produced a convincing defense of Roe on its own terms."[34] Liberal law professors Alan Dershowitz,[35] Cass Sunstein,[36] and Kermit Roosevelt[37] have also expressed disappointment with Roe.

Public opinion

- See also: Abortion in the United States: Public opinion

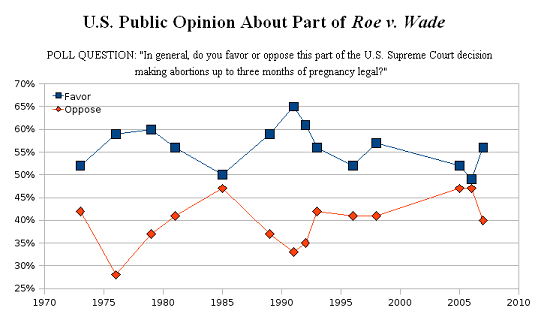

An October 2007 Harris poll on Roe v. Wade asked the following question:

| “ | In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that states laws which made it illegal for a woman to have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy were unconstitutional, and that the decision on whether a woman should have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy should be left to the woman and her doctor to decide. In general, do you favor or oppose this part of the U.S. Supreme Court decision making abortions up to three months of pregnancy legal?[38] | ” |

In reply, 56 percent of respondents indicated favor while 40 percent indicated opposition. The Harris organization concluded from this poll that "56 percent now favors the U.S. Supreme Court decision." Pro-life activists have disputed whether the Harris poll question is a valid measure of public opinion about Roe's overall decision, because the question focuses only on the first three months of pregnancy.[39] [40] The Harris poll has tracked public opinion about Roe since 1973:[41][38]

Regarding the Roe decision as a whole, more Americans support it than support overturning it.[42] When pollsters describe various regulations that Roe prevents legislatures from enacting, support for Roe drops substantially.[42][43]

Role in subsequent decisions and politics

Opposition to Roe on the bench grew when President Reagan—who supported legislative restrictions on abortion—began making federal judicial appointments in 1981. Reagan denied that there was any litmus test: "I have never given a litmus test to anyone that I have appointed to the bench…. I feel very strongly about those social issues, but I also place my confidence in the fact that the one thing that I do seek are judges that will interpret the law and not write the law. We've had too many examples in recent years of courts and judges legislating."[44]

In addition to White and Rehnquist, Reagan appointee Sandra Day O'Connor began dissenting from the Court's abortion cases, arguing in 1983 that the trimester-based analysis devised by the Roe Court was "unworkable."[45] Shortly before his retirement from the bench, Chief Justice Warren Burger suggested in 1986 that Roe be "reexamined";[46] the associate justice who filled Burger's place on the Court—Justice Antonin Scalia—vigorously opposed Roe. Concern about overturning Roe played a major role in the defeat of Robert Bork's nomination to the Court in 1987; the man eventually appointed to replace Roe-supporter Lewis Powell was Anthony M. Kennedy.

The Supreme Court of Canada used the rulings in both Roe and Doe v. Bolton as grounds to find Canada's federal law restricting access to abortions unconstitutional. That Canadian case, R. v. Morgentaler, was decided in 1988.[47]

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services

In a 5-4 decision in 1989's Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, Chief Justice Rehnquist, writing for the Court, declined to explicitly overrule Roe, because "none of the challenged provisions of the Missouri Act properly before us conflict with the Constitution,"[48] In this case, the Court upheld several abortion restrictions, and modified the Roe trimester framework.[48]

In concurring opinions, O'Connor refused to reconsider Roe, and Justice Antonin Scalia criticized the Court and O'Connor for not overruling Roe.[48] Blackmun – author of the Roe opinion – stated in his dissent that White, Kennedy and Rehnquist were "callous" and "deceptive," that they deserved to be charged with "cowardice and illegitimacy," and that their plurality opinion "foments disregard for the law."[48] White had recently opined that Blackmun was "warped."[46]

Planned Parenthood v. Casey

With the retirement of Roe supporters William J. Brennan in 1990 and Thurgood Marshall in 1991, and their replacement by David Souter and Clarence Thomas, pro-choice advocates viewed Roe for the first time as being in danger.[49] During the confirmation hearings of David Souter, NOW president Molly Yard declared that confirming Souter would mean "ending freedom for women in this country."[50]

According to NPR, in deliberations for Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), an initial majority of five Justices that would have overturned Roe foundered when Justice Kennedy switched sides.[51] O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter joined Blackmun and Stevens to reaffirm the central holding of Roe, saying, "At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life."[52] Rehnquist and Scalia signed each others' dissenting opinions; White and Thomas signed those dissenting opinions as well.

Scalia's dissent acknowledged that abortion rights are of "great importance to many women", but asserted that it is not a liberty protected by the Constitution, because the Constitution does not mention it, and because longstanding traditions have permitted it to be legally proscribed. Scalia concluded: "[B]y foreclosing all democratic outlet for the deep passions this issue arouses, by banishing the issue from the political forum that gives all participants, even the losers, the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight, by continuing the imposition of a rigid national rule instead of allowing for regional differences, the Court merely prolongs and intensifies the anguish."[52]

Stenberg v. Carhart

During the 1990s, Nebraska attempted to ban certain second-trimester abortion procedures sometimes called partial birth abortions. The Nebraska ban allowed other second-trimester abortion procedures called dilation and evacuation abortions. Ginsburg (who replaced White) stated, "this law does not save any fetus from destruction, for it targets only 'a method of performing abortion'."[53] The Supreme Court struck down the Nebraska ban by a 5-4 vote in Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), citing a right to use the safest method of abortion.

Kennedy, who had co-authored the 5-4 Casey decision upholding Roe, was among the dissenters in Stenberg, writing that Nebraska had done nothing unconstitutional.[53] Kennedy described the second trimester abortion procedure that Nebraska was not seeking to prohibit: "The fetus, in many cases, dies just as a human adult or child would: It bleeds to death as it is torn from limb from limb. The fetus can be alive at the beginning of the dismemberment process and can survive for a time while its limbs are being torn off." Kennedy wrote that since this dilation and evacuation procedure remained available in Nebraska, the state was free to ban the other procedure known as partial birth abortion.[53]

The remaining three dissenters in Stenberg – Thomas, Scalia, and Rehnquist – disagreed again with Roe: "Although a State may permit abortion, nothing in the Constitution dictates that a State must do so."

Gonzales v. Carhart

In 2003, Congress passed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which led to a lawsuit in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart. The Court had previously ruled in Stenberg v. Carhart that a state's ban on partial birth abortion was unconstitutional because such a ban would not allow for the health of the mother. The membership of the Court changed after Stenberg, with John Roberts and Samuel Alito replacing Rehnquist and O'Connor, respectively. Further, the ban at issue in Gonzales v. Carhart was a federal statute, rather than a relatively vague state statute as in the Stenberg case.

On April 18, 2007, the Supreme Court handed down a 5 to 4 decision upholding the constitutionality of the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act. Kennedy wrote for the five-justice majority that Congress was within its power to generally ban the procedure, although the Court left the door open for as-applied challenges. Kennedy's opinion did not reach the question whether the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and Stenberg v. Carhart were valid, and instead the Court said that the challenged statute is consistent with those prior decisions whether or not those prior decisions were valid.

Joining the majority were Chief Justice John Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito. Ginsburg and the other three justices dissented, contending that the ruling ignored Supreme Court abortion precedent, and also offering an equality-based justification for that abortion precedent. Thomas filed a concurring opinion, joined by Scalia, contending that the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey should be reversed, and also noting that the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act may exceed the powers of Congress under the Commerce Clause.

Activities of Norma McCorvey

Norma McCorvey became a member of the pro-life movement in 1995; she now supports making abortion illegal. In 1998, she testified to Congress:

| “ | It was my pseudonym, Jane Roe, which had been used to create the "right" to abortion out of legal thin air. But Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee never told me that what I was signing would allow women to come up to me 15, 20 years later and say, "Thank you for allowing me to have my five or six abortions. Without you, it wouldn't have been possible." Sarah never mentioned women using abortions as a form of birth control. We talked about truly desperate and needy women, not women already wearing maternity clothes.[5] | ” |

As a party to the original litigation, she sought to reopen the case in U.S. District Court in Texas to have Roe v. Wade overturned. However, the Fifth Circuit decided that her case was moot, in McCorvey v. Hill.[54] In a concurring opinion, Judge Edith Jones agreed that McCorvey was raising legitimate questions about emotional and other harm suffered by women who have had abortions, about increased resources available for the care of unwanted children, and about new scientific understanding of fetal development, but Jones said she was compelled to agree that the case was moot. On February 22, 2005, the Supreme Court refused to grant a writ of certiorari, and McCorvey's appeal ended.

Presidential positions

The Roe decision was opposed by Presidents Gerald Ford,[55] Ronald Reagan,[56] and George W. Bush.[57] President George H.W. Bush also opposed Roe, though he had supported abortion rights earlier in his career.[58][59]

Jimmy Carter supported legal abortion from an early point in his political career, in order to prevent birth defects and in other extreme cases; he encouraged the outcome in Roe and generally supported abortion rights.[60] Roe was also supported by President Bill Clinton.[61] President-elect Barack Obama has taken the position that, "Abortions should be legally available in accordance with Roe v. Wade."[62]

Richard Nixon, who was President when the Roe decision occurred, did not believe abortion was an acceptable form of population control. Nixon did not publicly comment about the decision.[63]

State laws regarding Roe

Several states have enacted so-called "trigger laws" which "would take effect if Roe v. Wade is overturned."[64] Those states include Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota and South Dakota.[65] Additionally, many states did not repeal pre-1973 statutes that criminalized abortion, and some of those statutes could automatically spring back to life in the event of a reversal of Roe.[66]

Other states have passed laws to maintain the legality of abortion if Roe v. Wade is overturned. Those states include California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Nevada and Washington.[65]

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 410

- Pro-Choice

- Pro-Life

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ William Mears and Bob Franken, “30 years after ruling, ambiguity, anxiety surround abortion debate”, CNN (2003-01-22): “In all, the Roe and Doe rulings impacted laws in 46 states.”

- ↑ Richard Ostling. "A second religious conversion for 'Jane Roe' of Roe vs. Wade", Associated Press (1998-10-19). McCorvey recanted the rape claim years after the Roe decision.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 McCorvey, Norma. Testimony to the Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution, Federalism and Property Rights (1998-01-21), quoted in the parliament of Western Australia (PDF) (1998-05-20). Retrieved 2007-01-27

- ↑ Roe v. Wade, 314 F. Supp. 1217 (1970): "On the merits, plaintiffs argue as their principal contention that the Texas Abortion Laws must be declared unconstitutional because they deprive single women and married couple of their rights secured by the Ninth Amendment to choose whether to have children. We agree." Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ↑ O'Connor, Karen. Testimony before U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, "The Consequences of Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton" (2005-06-23). Retrieved 2007-01-30

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard. The Unpublished Opinions of the Burger Court, page 103 (1988 Oxford University Press), via Google Books. Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ Garrow David. Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe V. Wade (Univ. of Calif. 1998), p. 556. Retrieved 2007-01-30

- ↑ Cole, George; Frankowski, Stanislaw. Abortion and protection of the human fetus : legal problems in a cross-cultural perspective, page 20 (1987): "By 1900 every state in the Union had an anti-abortion prohibition." Via Google Books. Retrieved (2008-04-08).

- ↑ Abernathy, M. et al., Civil Liberties Under the Constitution (U. South Carolina 1993), page 4. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- ↑ Southern Pacific v. Interstate Commerce Commission, 219 U.S. 498 (1911). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ Paulsen, Michael Stokes. What Roe v. Wade Should Have Said; The Nation’s Top Legal Experts Rewrite America’s Most Controversial decision, Jack Balkin Ed. (NYU Press 2005). Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ Reagan, Ronald. Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation, (Nelson 1984): "If you don't know whether a body is alive or dead, you would never bury it. I think this consideration itself should be enough for all of us to insist on protecting the unborn." Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Koppelman, Andrew. “Forced Labor: A Thirteenth Amendment Defense of Abortion”, Northwestern Law Review, Volume 84, page 480 (1990).

- ↑ What Roe v. Wade Should Have Said; The Nation’s Top Legal Experts Rewrite America’s Most Controversial decision, Jack Balkin Ed. (NYU Press 2005). Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ Guttmacher Institute, "State Policies in Brief, An Overview of Abortion Laws (PDF)", published 2007-01-01. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Thomson, Judith. "A Defense of Abortion," in Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 1, no. 1 (1971), pp. 47–66.

- ↑ Woodward, Bob. "The Abortion Papers", Washington Post (1989-01-22). Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ Kmiec, Douglas. "Testimony Before Subcommittee on the Constitution, Judiciary Committee, U.S. House of Representatives" (1996-04-22), via the "Abortion Law Homepage." Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Bush, George Walker. Quoted in Boston Globe, p. A12 (2000-01-22). "Roe v. Wade was wrong because it 'usurped the power of the legislatures,' Bush said. 'I felt like it was a case where the court took the place of what legislatures should do in America,' he said. But Bush refused to say how he felt each state should act. Instead, he said that when it comes to legalizing abortion, 'it should be up to each legislature.'" Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ Stith, Irene. Abortion Procedures, CRS Report for Congress (PDF) (1997-11-17). Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ Balkin, Jack. Bush v. "Gore and the Boundary Between Law and Politics", 110 Yale Law Journal 1407 (2001): "Liberal and feminist legal scholars have spent decades showing that the result was correct even if Justice Blackmun’s opinion seems to have been taken from the Court’s Cubist period."

- ↑ Cohen, Richard. "Support Choice, Not Roe", Washington Post, (2005-10-19): "If the best we can say for it is that the end justifies the means, then we have not only lost the argument — but a bit of our soul as well." Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Saletan, William. "Unbecoming Justice Blackmun", Legal Affairs, May/June 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-23. Saletan is a self-described liberal. See Saletan, William. "Rights and Wrongs: Liberals, progressives, and biotechnology", Slate (2007-07-13).

- ↑ Ely, John Hart. "The Wages of Crying Wolf", Yale Law Journal 1973. Retrieved 2007-01-23. Professor Ely "supported the availability of abortion as a matter of policy." See Liptak, Adam. "John Hart Ely, a Constitutional Scholar, Is Dead at 64", New York Times (2003-10-27). Ely is generally regarded as having been a “liberal constitutional scholar.” Perry, Michael. We the People: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Supreme Court (1999) via Google books.

- ↑ Tribe, Laurence. "The Supreme Court, 1972 Term—Foreword: Toward a Model of Roles in the Due Process of Life and Law", 87 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 7 (1973). Quoted in Morgan, "Roe v. Wade and the Lesson of the Pre-Roe Case Law", Michigan Law Review, Vol. 77, No. 7, Symposium on the Law and Politics of Abortion (Aug., 1979), p. 1724, via JSTOR (see bottom of first page of Morgan's article). Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Cox, Archibald. The Role of the Supreme Court in American Government, 113–114 (Oxford U. Press 1976), via Google Books. Retrieved 2007-01-26. Stuart Taylor has noted that, "Roe v. Wade was sort of conjured up out of very general phrases and was recorded, even by most liberal scholars like Archibald Cox at the time, John Harvey Link - just to name two Harvard scholars - as kind of made-up constitutional law.” See Stuart Taylor Jr., Online News Hour, PBS 2000-07-13.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Ruth. "Some Thoughts on Autonomy and Equality in Relation to Roe v. Wade", 63 North Carolina Law Review 375 (1985): "The political process was moving in the early 1970s, not swiftly enough for advocates of quick, complete change, but majoritarian institutions were listening and acting. Heavy-handed judicial intervention was difficult to justify and appears to have provoked, not resolved, conflict." Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Rosen, Jeffrey. "Why We’d Be Better off Without Roe: Worst Choice", The New Republic via Archive.org(2003-02-24): “In short, 30 years later, it seems increasingly clear that this pro-choice magazine was correct in 1973 when it criticized Roe on constitutional grounds. Its overturning would be the best thing that could happen to the federal judiciary, the pro-choice movement, and the moderate majority of the American people.” Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Kinsley, Michael. "Bad choice", The New Republic (2004-06-13): "Against all odds (and, I'm afraid, against all logic), the basic holding of Roe v. Wade is secure in the Supreme Court....[A] freedom of choice law would guarantee abortion rights the correct way, democratically, rather than by constitutional origami." Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Wittes, Benjamin. "Letting Go of Roe", The Atlantic Monthly, Jan/Feb 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-23. Wittes also said, "I generally favor permissive abortion laws." Wittes has elsewhere noted that, "In their quieter moments many liberal scholars recognize that the decision is a mess." See Wittes, Benjamin. "A Little Less Conversation", The New Republic 2007-11-29

- ↑ Lazarus, Edward. "The Lingering Problems with Roe v. Wade, and Why the Recent Senate Hearings on Michael McConnell’s Nomination Only Underlined Them", Findlaw's Writ (2002-10-03). Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Dershowitz, Alan. Supreme Injustice: How the High Court Hijacked Election 2000 (Oxford U. Press 2001): “Judges have no special competence, qualifications, or mandate to decide between equally compelling moral claims (as in the abortion controversy)....” quoted by Green, "Bushed and Gored: A Brief Review of Initial Literature", in The Final Arbiter: The Consequences of Bush V. Gore for Law And Politics, ed. Banks C, Cohen D & Green J., editors, page 14 (SUNY Press 2005), via Google Books. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Sunstein, Cass. Quoted by McGuire, New York Sun (2005-11-15): "What I think is that it just doesn't have the stable status of Brown or Miranda because it's been under internal and external assault pretty much from the beginning....As a constitutional matter, I think Roe was way overreached.” Retrieved 2007-01-23. Sunstein is a "liberal constitutional scholar." See Herman, Eric. "Former U of C law prof on everyone's short court list", Chicago Sun-Times (2005-07-11).

- ↑ Roosevelt, Kermit. "Shaky Basis for a Constitutional ‘Right’", Washington Post, (2003-01-22): "[I]t is time to admit in public that, as an example of the practice of constitutional opinion writing, Roe is a serious disappointment. You will be hard-pressed to find a constitutional law professor, even among those who support the idea of constitutional protection for the right to choose, who will embrace the opinion itself rather than the result….This is not surprising. As constitutional argument, Roe is barely coherent. The court pulled its fundamental right to choose more or less from the constitutional ether. It supported that right via a lengthy, but purposeless, cross-cultural historical review of abortion restrictions and a tidy but irrelevant refutation of the straw-man argument that a fetus is a constitutional ‘person’ entited to the protection of the 14th Amendment....By declaring an inviolable fundamental right to abortion, Roe short-circuited the democratic deliberation that is the most reliable method of deciding questions of competing values." Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Harris Interactive, (2007-11-09). "Support for Roe v. Wade Increases Significantly, Reaches Highest Level in Nine Years." Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ Franz, Wanda. "The Continuing Confusion About Roe v. Wade", NRL News (June 2007).

- ↑ Adamek, Raymond. "Abortion Polls", Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 411-413. Dr. Adamek is pro-life. Dr Raymond J Adamek, PhD Pro-Life Science and Technology Symposium.

- ↑ Harris Interactive. 'U.S. Attitudes Toward Roe v. Wade". The Wall Street Journal Online, (2006-05-04). Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Ayres McHenry Poll Results on Roe v. Wade via Angus Reid Global Monitor (2007).

- ↑ Gallagher, Maggie. “Pro-Life Voters are Crucial Component of Electability”, Realclearpolitics.com (2007-05-23).

- ↑ Reagan, Ronald. Interview With Eleanor Clift, Jack Nelson, and Joel Havemann of the Los Angeles Times (1986-06-23). Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health Inc., 462 U.S. 416 (1983). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747 (1986). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ R. v. Morgentaler 1 S.C.R. 30 (1988).

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ Wattleton, Faye. Testimony before the Senate Judiciary committee on the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the United States Supreme Court (PDF) (1991-09-19). Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ Yard, Molly. Quoted in Kamen, "For Liberals, Easy Does it With Roberts", Washington Post (2005-09-19). Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Totenberg, Nina. "Documents Reveal Battle to Preserve 'Roe'; Court Nearly Reversed Abortion Ruling, Blackmun Papers Show", NPR's Morning Edition (2004-03-04). Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992). Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000). Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ McCorvey v. Hill, 385 F3d 846 (PDF) (5th Cir 2004). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 2007-01-26

- ↑ Ford, Gerald. Letter to the Archbishop of Cincinnati, published online by The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California (1976-09-10).

- ↑ Reagan, Ronald. Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation (Nelson 1984).

- ↑ Bush, George Walker. "Bush Tells Addicts He Can Identify," Boston Globe, p. A12 (2000-01-22).

- ↑ Fritz, Sara. “'92 REPUBLICAN CONVENTION: Rigid Anti-Abortion Platform Plank OKd Policy: Activists opposed to GOP stand wear pink satin armbands in convention hall as a protest. Issue clearly will continue to divide party”, Los Angeles Times (1992-08-18): “President George Bush supported abortion rights until 1980, when he switched sides after Ronald Reagan picked Bush as his running mate.”

- ↑ Bush, George Herbert Walker.Remarks to Participants in the March for Life Rally (1989-01-23).

- ↑ Carter, James Earl. Larry King Live, CNN, Interview With Jimmy Carter (2006-02-01). Also see Bourne, Peter, Jimmy Carter: A Comprehensive Biography from Plains to Postpresidency: "Early in his term as governor, Carter had strongly supported family planning programs including abortion in order to save the life of a mother, birth defects, or in other extreme circumstances. Years later, he had written the foreword to a book, Women in Need, that favored a woman's right to abortion. He had given private encouragement to the plaintiffs in a lawsuit, Doe v. Bolton, filed against the state of Georgia to overturn its archaic abortion laws."

- ↑ Clinton, Bill. My Life, page 229 (Knopf 2004).

- ↑ Obama, Barack. "1998 Illinois State Legislative National Political Awareness Test", Project Vote Smart. Retrieved on 2007-01-21.

- ↑ Reeves, Richard. President Nixon: Alone in the White House, page 563 (2001): "The President did not comment directly on the decision."

- ↑ "Blanco signs law that would ban abortions", Reuters via The Peninsula (2006-06-17). Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Vestal, Christine. "States probe limits of abortion policy", Stateline.org (2007-06-11).

- ↑ Marcus, Frances Frank. “Louisiana Moves Against Abortion”, New York Times (1989-07-08).

References

- Critchlow, Donald T. (1996). The Politics of Abortion and Birth Control in Historical Perspective. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0271015705.

- Critchlow, Donald T. (1999). Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195046579.

- Garrow, David J. (1994). Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe v. Wade. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0025427555.

- Hull, N.E.H. (2004). The Abortion Rights Controversy in America: A Legal Reader. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807828734.

- Hull, N.E.H.; Peter Charles Hoffer (2001). Roe v. Wade: The Abortion Rights Controversy in American History. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700611436.

- Mohr, James C. (1979). Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy, 1800–1900. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195026160.

- Rubin, Eva R. [ed.] (1994). The Abortion Controversy: A Documentary History. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0313284768.

- Staggenborg, Suzanne (1994). The Pro-Choice Movement: Organization and Activism in the Abortion Conflict. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195065964.

External links

- Full text of opinion with links to cited material

- Audio of oral argument at www.oyez.org

|

|||||||||||