Rocky Mountains

| Rocky Mountains | |

| Rockies | |

| Mountain range | |

|

|

| Countries | Canada, United States |

|---|---|

| Regions | British Columbia, Alberta, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico |

| Part of | Pacific Cordillera |

| Highest point | Mount Elbert |

| - elevation | 14,440 ft (4,401 m) |

| - coordinates | |

| Geology | Igneous, Sedimentary, Metamorphic |

| Period | Precambrian, Cretaceous |

|

|

- See also: Mountain peaks of the Rocky Mountains

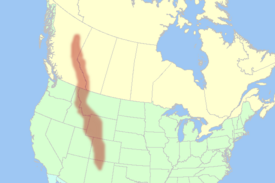

The Rocky Mountains, often called the Rockies, are a mountain range in western North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch more than 4,800 kilometers (3,000 miles) from northernmost British Columbia, in Canada, to New Mexico, in the United States. The range's highest peak is Mount Elbert in Colorado at 14,440 feet (4,401 meters) above sea level. Though part of North America's Pacific Cordillera, the Rockies are distinct from the Pacific Coast Ranges, which are located immediately adjacent to the Pacific coast.

The eastern edge of the Rockies rises impressively above the Interior Plains of central North America, including the Front Range which runs from northern New Mexico to northern Colorado, the Wind River Range and Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming, the Crazy Mountains and the Rocky Mountain Front of Montana, and the Clark Range of Alberta. In Canada geographers define three main groups of ranges: the Continental Ranges, Hart Ranges and Muskwa Ranges (the latter two flank the Peace River, the only river to pierce the Rockies, and are collectively referred to as the Northern Rockies). Mount Robson in British Columbia, at 3,954 meters (12,972 ft), is the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies.

The western edge of the Rockies, such as the Wasatch Range near Salt Lake City, Utah, divides the Great Basin from other mountains further to the west. The Rockies do not extend into the Yukon or Alaska, or into central British Columbia, where the Rocky Mountain System (but not the Rocky Mountains) includes the Columbia Mountains, the southward extension of which is considered part of the Rockies in the United States. The Rocky Mountain System within the United States is a United States physiographic region.

Contents |

Geography and geology

- See also: Geography of the United States Rocky Mountain System and Geology of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains are commonly defined as stretching from the Liard River in British Columbia south to the Rio Grande in New Mexico. Other mountain ranges continue beyond those two rivers, including the Selwyn Range in Yukon, the Brooks Range in Alaska, and the Sierra Madre in Mexico, but those are not part of the Rockies, though they are part of the American cordillera. The United States definition of the Rockies, however, includes the Cabinet and Salish Mountains of Idaho and Montana, whereas their counterparts north of the Kootenai River, the Columbia Mountains, are considered a separate system in Canada, lying to the west of the huge Rocky Mountain Trench, which runs the length of British Columbia from its beginnings in the middle Flathead River valley in western Montana to the south bank of the Liard River. The Rockies vary in width from 70 to 300 miles (110 to 480 kilometers). Also west of the Rocky Mountain Trench, farther north and facing the Muskwa Ranges across the trench, are the Stikine Ranges and Omineca Mountains of the Interior Mountains system of British Columbia.

The younger ranges of the Rocky Mountains uplifted during the late Cretaceous period (100 million – 65 million years ago), although some portions of the southern mountains date from uplifts during the Precambrian (3,980 million – 600 million years ago). The mountains' geology is a complex of igneous and metamorphic rock; younger sedimentary rock occurs along the margins of the southern Rocky Mountains, and volcanic rock from the Tertiary (65 million – 1.8 million years ago) occurs in the San Juan Mountains and in other areas. Millennia of severe erosion in the Wyoming Basin transformed intermountain basins into a relatively flat terrain. The Tetons and other north-central ranges contain folded and faulted rocks of Paleozoic and Mesozoic age draped above cores of Proterozoic and Archean igneous and metamorphic rocks ranging in age from 1.2 billion (e.g., Tetons) to more than 3.3 billion years (Beartooth Mountains).[1]

Periods of glaciation occurred from the Pleistocene Epoch (1.8 million – 70,000 years ago) to the Holocene Epoch (fewer than 11,000 years ago). Recent episodes included the Bull Lake Glaciation that began about 150,000 years ago and the Pinedale Glaciation that probably remained at full glaciation until 15,000–20,000 years ago.[1][2] Ninety percent of Yellowstone National Park was covered by ice during the Pinedale Glaciation.[1]The little ice age was a period of glacial advance that lasted a few centuries from about 1550 to 1860. For example, the Agassiz and Jackson glaciers in Glacier National Park reached their most forward positions about 1860 during the little ice age.[1]

Water in its many forms sculpted the present Rocky Mountain landscape.[1] Runoff and snowmelt from the peaks feed Rocky Mountain rivers and lakes with the water supply for one-quarter of the United States. The rivers that flow from the Rocky Mountains eventually drain into three of the world's Oceans: the Atlantic Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, and the Arctic Ocean.[1] These rivers include:

- Gulf of Mexico drainage

- Arkansas River

- Platte River

- Rio Grande

- Missouri River

- Wind River

- Yellowstone River

- Arctic Ocean drainage

- Athabasca River

- Peace River

- Parsnip River

- Misinchinka River

- Parsnip River

- Finlay River

- Liard River

- Muskwa River

- Kechika River

- Gataga River

- Toad River

- Northwest Pacific Ocean drainage

- Columbia River

- Kicking Horse River

- Blaeberry River

- Bush River

- Wood River

- Bitterroot River

- Kootenay River

- Elk River

- Bull River

- Vermilion River

- Clark Fork River

- Clearwater River

- Coeur d'Alene River

- Salmon River

- Snake River

- Payette River

- Selway River

- Lochsa River

- Fraser River

- McGregor River

- Gulf of California drainage

- Colorado River

- Green River

- Hudson Bay drainage

- North Saskatchewan River

- South Saskatchewan River

- Bow River

- Oldman River

- Red Deer River

The Continental Divide is located in the Rocky Mountains and designates the line at which waters flow either to the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. Triple Divide Peak (8,020 feet / 2,444 m) in Glacier National Park (U.S.) is so named because water that falls on the mountain reaches not only the Atlantic and Pacific, but Hudson Bay as well. Farther north in Alberta, the Athabasca and other rivers feed the basin of the Mackenzie River, which has its outlet on the Beaufort Sea of the Arctic Ocean.

Human history

Since the last great Ice Age, the Rocky Mountains were home first to Paleo-Indians and then to the indigenous peoples of the Apache, Arapaho, Bannock, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Crow, Flathead, Shoshoni, Sioux, Ute, Kutenai (Ktunaxa in Canada), Sekani, Dunne-za, and others.[1] Paleo-Indians hunted the now-extinct mammoth and ancient bison (an animal 20% larger than modern bison) in the foothills and valleys of the mountains. Like the modern tribes that followed them, Paleo-Indians probably migrated to the plains in fall and winter for bison and to the mountains in spring and summer for fish, deer, elk, roots, and berries. In Colorado, along the crest of the Continental Divide, rock walls that Native Americans built for driving game date back 5,400–5,800 years.[1] A growing body of scientific evidence indicates that indigenous peoples had significant effects on mammal populations by hunting and on vegetation patterns through deliberate burning.[1]

Recent human history of the Rocky Mountains is one of more rapid change.[1] The Spanish explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado—with a group of soldiers, missionaries, and African slaves—marched into the Rocky Mountain region from the south in 1540. The introduction of the horse, metal tools, rifles, new diseases, and different cultures profoundly changed the Native American cultures. Native American populations were extirpated from most of their historical ranges by disease, warfare, habitat loss (eradication of the bison), and continued assaults on their culture.[1]

In 1739, French fur traders Pierre and Paul Mallet, while journeying through the Great Plains, discovered a range of mountains at the headwaters of the Platte River, which local American Indian tribes called the "Rockies", becoming the first Europeans to report on this uncharted mountain range.[3]

Sir Alexander MacKenzie (1764 – March 11, 1820) became the first European to cross the Rocky Mountains in 1793. He found the upper reaches of the Fraser River and reached the Pacific coast of what is now Canada on July 20 of that year, completing the first recorded transcontinental crossing of North America north of Mexico. He arrived at Bella Coola, British Columbia, where he first reached saltwater at South Bentinck Arm, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) was the first scientific reconnaissance of the Rocky Mountains. Specimens were collected for contemporary botanists, zoologists, and geologists.[1] The expedition was said to have paved the way to (and through) the Rocky Mountains for European-Americans from the East, although Lewis and Clark met at least 11 European-American mountain men during their travels.[1]

Mountain men, primarily French, Spanish, and British, roamed the Rocky Mountains from 1720 to 1800 seeking mineral deposits and furs. The fur-trading North West Company established Rocky Mountain House as a trading post in what is now the Rocky Mountain foothills of present-day Alberta in 1799, and their business rivals the Hudson's Bay Company established Acton House nearby. These posts served as bases for most European activity in the Canadian Rockies in the early 1800s, most notably the expeditions of David Thompson (explorer), the fourth European to follow the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. After 1802, American fur traders and explorers ushered in the first widespread caucasian presence in the Rockies south of the 49th parallel. The more famous of these include Americans included William Henry Ashley, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, John Colter, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Andrew Henry, and Jedediah Smith. On July 24, 1832, Benjamin Bonneville led the first wagon train across the Rocky Mountains by using Wyoming's South Pass.[1]

Thousands passed through the Rocky Mountains on the Oregon Trail beginning in 1842. The Mormons began to settle near the Great Salt Lake in 1847. From 1859 to 1864, Gold was discovered in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia sparking several gold rushes bringing thousands of prospectors and miners to explore every mountain and canyon and to create the Rocky Mountain's first major industry. The Idaho gold rush alone produced more gold than the California and Alaska gold rushes combined and was important in the financing of the Union Army during the American Civil War. The transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, and Yellowstone National Park was established as the world's first national park in 1872. While settlers filled the valleys and mining towns, conservation and preservation ethics began to take hold. U.S. President Harrison established several forest reserves in the Rocky Mountains in 1891–1892. In 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt extended the Medicine Bow Forest Reserve to include the area now managed as Rocky Mountain National Park.[1] Economic development began to center on mining, forestry, agriculture, and recreation, as well as on the service industries that support them.[1] Tents and camps became ranches and farms, forts and train stations became towns, and some towns became cities.[1]

Industry and development

Economic resources of the Rocky Mountains are varied and abundant. Minerals found in the Rocky Mountains include significant deposits of copper, gold, lead, molybdenum, silver, tungsten, and zinc. The Wyoming Basin and several smaller areas contain significant reserves of coal, natural gas, oil shale, and petroleum. For example, the Climax mine, located near Leadville, Colorado, was the largest producer of Molybdenum in the world. Molybdenum is used in heat-resistant steel in such things as cars and planes. The Climax mine employed over 3,000 workers. The Coeur d’Alene mine of northern Idaho produces silver, lead, and zinc. Canada's largest coal mines are near Fernie, British Columbia and Sparwood, British Columbia; additional coal mines exist near Hinton, Alberta,[1] and in the Northern Rockies surrounding Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia.

Abandoned mines with their wakes of mine tailings and toxic wastes dot the Rocky Mountain landscape. In one major example, eighty years of zinc mining profoundly polluted the river and bank near Eagle River in north-central Colorado. High concentrations of the metal carried by spring runoff harmed algae, moss, and trout populations. An economic analysis of mining effects at this site revealed declining property values, degraded water quality, and the loss of recreational opportunities. The analysis also revealed that cleanup of the river could yield $2.3 million in additional revenue from recreation. In 1983, the former owner of the zinc mine was sued by the Colorado Attorney General for the $4.8 million cleanup costs; five years later, ecological recovery was considerable.[1][4]

Agriculture and forestry are major industries. Agriculture includes dryland and irrigated farming and livestock grazing. Livestock are frequently moved between high-elevation summer pastures and low-elevation winter pastures,[1] a practice known as transhumance.

Human population is not very dense in the Rocky Mountains, with an average of four people per square kilometer (10 per square mile) and few cities with over 50,000 people. However, the human population grew rapidly in the Rocky Mountain states between 1950 and 1990. The 40-year statewide increases in population range from 35% in Montana to about 150% in Utah and Colorado. The populations of several mountain towns and communities have doubled in the last 40 years. Jackson Hole, Wyoming, increased 260%, from 1,244 to 4,472 residents, in 40 years.[1]

Tourism

See also: List of U.S. Rocky Mountain ski resorts, List of Alberta ski resorts, List of B.C. ski resorts

Every year the scenic areas and recreational opportunities of the Rocky Mountains draw millions of tourists.[1] The main language of the Rocky Mountains is English. But there are also linguistic pockets of Spanish and Native American languages.

People from all over the world visit the sites to hike, camp, or engage in mountain sports.[1] In the summer season, the main tourist attractions are:

In the United States:

- Pikes Peak

- Royal Gorge

- Rocky Mountain National Park

- Yellowstone National Park

- Grand Teton National Park

- Glacier National Park (U.S.)

- Sawtooth National Recreation Area

In Canada, the mountain range contains these national parks:

- Banff National Park

- Jasper National Park

- Kootenay National Park

- Waterton Lakes National Park

- Yoho National Park

Glacier National Park in Montana and Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta border each other and collectively are known as Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. (See also International Peace Park.)

In the winter, skiing is the main attraction. A list of the major ski resorts can be found at List of U.S. Rocky Mountain ski resorts.

The adjacent Columbia Mountains in British Columbia contain major resorts such as, Fernie, Panorama and Kicking Horse, as well as Mount Revelstoke National Park.

Climate

The Rocky Mountains have a highland climate. The average annual temperature in the valley bottoms of the Colorado Rockies near the latitude of Boulder is 43 °F (6 °C). July is the hottest month there with an average temperature of 82 °F (28 °C). In January, the average monthly temperature is 7 °F (−14 °C), making it the region's coldest month. The average precipitation per year there is approximately 14 inches (360 mm).

The summers in this area of the Rockies are warm and dry, because the western fronts impede the advancing of water-carrying storm systems. The average temperature in summer is 59 °F (15 °C) and the average precipitation is 5.9 inches (150 mm). Winter is usually wet and very cold, with an average temperature of 28 °F (−2 °C) and average snowfall of 11.4 inches (29.0 cm). In spring, the average temperature is 40 °F (4 °C) and the average precipitation is 4.2 inches (107 mm). And in the fall, the average precipitation is 2.6 inches (66 mm) and the average temperature is 44 °F (7 °C).

See also

- Geography of the United States Rocky Mountain System

- Canadian Rockies

- Southern Rocky Mountains

- Colorado mountain passes

- Mountain peaks of Colorado

- Mountain ranges of Colorado

- Geology of the Rocky Mountains

- Mountain peaks of the Rocky Mountains

- Rocky Mountains subalpine zone

- Geography of North America

- Geology of North America

- Lists of mountains

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 Stohlgren, T.J. (1998). "Rocky Mountains". in M.J. Mac, P.A. Opler, C.E. Puckett Haeker, and P.D. Doran. Status and Trends of the Nation's Biological Resources. Reston, Va.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. http://web.archive.org/web/20060927145110/http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/SNT/noframe/wm146.htm. (public domain source)

- ↑ Pierce, K. L. (1979). History and dynamics of glaciation in the northern Yellowstone National Park area. Washington, D.C: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 1–90. Professional Paper 729-F.

- ↑ PBS—THE WEST—Events from 1650 to 1800

- ↑ Brandt, E. (1993). "How much is a gray wolf worth?". National Wildlife 31: 412.

External links

- U.S. Geological Survey website on the Rocky Mountains

- Headwaters News—Headwaters News—Reporting on the Rockies

- Colorado Rockies Forests ecoregion images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- North Central Rockies Forests ecoregion images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- South Central Rockies Forests ecoregion images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||