Robinson Crusoe

| Robinson Crusoe | |

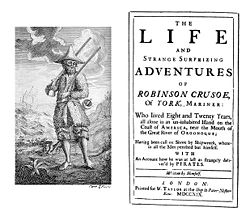

Title page from the first edition |

|

| Author | Daniel Defoe |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Publication date | April 25, 1719 |

| Followed by | The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe |

Robinson Crusoe is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1719 and sometimes regarded as the first novel in English. The book is a fictional autobiography of the title character, an English castaway who spends 28 years on a remote tropical island near Venezuela, encountering Native Americans, captives, and mutineers before being rescued. This device, presenting an account of supposedly factual events, is known as a "false document" and gives a realistic frame story.

The story was likely influenced by the real-life Alexander Selkirk, a Scottish castaway who lived four years on the Pacific island called Más a Tierra (in 1966 its name was changed to Robinson Crusoe Island), Chile. However, the details of Crusoe's island were probably based on the Caribbean island of Tobago, since that island lies a short distance north of the Venezuelan coast near the mouth of the Orinoco river, and in sight of the island of Trinidad.[1] It is also likely that Defoe was inspired by the Latin or English translations of Ibn Tufail's Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, an earlier novel also set on a desert island. [2][3] [4] [5] Another source for Defoe's novel may have been Robert Knox's account of his abduction by the King of Ceylon in 1659 in "An Historical Account of the Island Ceylon," Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons (Publishers to the University), 1911.[6]

Contents |

Plot summary

Crusoe leaves England, setting sail from the Queens Dock in Hull on a sea voyage in September 1651, against the wishes of his parents, who want him to stay home and become a businessman. After a tumultuous journey that sees his ship wrecked by a vicious storm, his lust for the sea remains so strong that he sets out to sea again. This journey too ends in disaster as the ship is taken over by Salé pirates, and Crusoe becomes the slave of a Moor. He manages to escape with a boat and a boy named Xury; later, Robin is befriended by the Captain of a Portuguese ship off the western coast of Africa. The ship is enroute to Brazil. There, with the help of the captain, Crusoe becomes owner of a plantation.

Years later, he joins an expedition to bring slaves from Africa, but is shipwrecked in a storm about forty miles out to sea on an island (which he calls the Island of Despair) near the mouth of the Orinoco river on September 30, 1659. His companions all die. Having overcome his despair, he fetches arms, tools, and other supplies from the ship before it breaks apart and sinks. He proceeds to build a fenced-in habitation near a cave which he excavates himself. He keeps a calendar by making marks in a wooden cross built by himself, hunts, grows corn, learns to make pottery, raises goats, etc., using tools created from stone and wood which he harvests on the island, and adopts a small parrot. He reads the Bible and suddenly becomes religious, thanking God for his fate in which nothing is missing but society.

Years later, he discovers native cannibals who occasionally visit the island to kill and eat prisoners. At first he plans to kill them for committing an abomination, but later realizes that he has no right to do so as the cannibals have not attacked him and do not knowingly commit a crime. He dreams of obtaining one or two servants by freeing some prisoners; and indeed, when a prisoner manages to escape, Crusoe helps him, naming his new companion "Friday" after the day of the week he appeared. Crusoe then teaches him English and converts him to Christianity.

After another party of natives arrive to partake in a cannibal feast, Crusoe and Friday manage to kill most of the natives and save two of the prisoners. One is Friday's father and the other is a Spaniard, who informs Crusoe that there are other Spaniards shipwrecked on the mainland. A plan is devised wherein the Spaniard would return with Friday's father to the mainland and bring back the others, build a ship, and sail to a Spanish port.

Before the Spaniards return, an English ship appears; mutineers have taken control of the ship and intend to maroon their former captain on the island. Crusoe and the ship's captain strike a deal, in which he helps the captain and the loyalist sailors retake the ship from the mutineers, whereupon they intend to leave the worst of the mutineers on the island. Before they leave for England, Crusoe shows the former mutineers how he lived on the island, and states that there will be more men coming. Crusoe leaves the island December 19th, 1686, and arrives back in England June 11th, 1687. He learns that his family believed him dead and there was nothing in his father's will for him. However, his estate in Brazil granted him some wealth.

Reception and sequels

The book was published on April 25, 1719. Its full title was The Life and strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, where-in all the Men perished but himself. With An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver'd by Pyrates. Written by Himself

The positive reception was immediate and universal. Before the end of the year, this first volume had run through four editions. Within years, it had reached an audience as wide as any book ever written in English.

By the end of the 19th century, no book in the history of Western literature had spawned more editions, spin-offs, and translations (even into languages such as Inuit, Coptic, and Maltese) than Robinson Crusoe, with more than 700 such alternative versions, including children's versions with mainly pictures and no text.[7] There have been hundreds of adaptations in dozens of languages, from The Swiss Family Robinson to Luis Buñuel's film adaptation. J.M. Coetzee's 1986 novel Foe and the 2000 Hollywood film Cast Away are both recent examples of reimagining, retelling, and reevaluation of the story.

The term "Robinsonade" has been coined to describe the genre of stories similar to Robinson Crusoe.

Defoe went on to write a lesser-known sequel, The Farther Adventures of My Family and I. It was intended to be the last part of his stories, according to the original title-page of its first edition, but in fact a third part, entitled Serious Reflections of Robinson Crusoe, was written; it is a mostly forgotten series of moral essays with Crusoe's name attached to give interest.

Real-life castaways

- See also: Castaway#Real Occurrences

There were many stories of real-life castaways in Defoe's time. Defoe's initial inspiration for Crusoe is usually thought to be a Scottish sailor named Alexander Selkirk, who was rescued in 1709 by Woodes Rogers' expedition after four years on the uninhabited island of Más a Tierra in the Juan Fernández Islands off the Chilean coast. Rogers' "Cruising Voyage" was published in 1712, with an account of Alexander Selkirk's ordeal. However, Robinson Crusoe is far from a copy of Woodes Rogers' account: Selkirk was marooned at his own request, while Crusoe was shipwrecked; the islands are different; Selkirk lived alone for the whole time, while Crusoe found companions; while Selkirk stayed on his island for four years, not twenty-eight. Furthermore, much of the appeal of Defoe's novel is the detailed and captivating account of Crusoe's thoughts, occupations and activities which goes far beyond that of Rogers' basic descriptions of Selkirk, which account for only a few pages.

Tim Severin's book Seeking Robinson Crusoe (2002) unravels a much wider and more plausible range of potential sources of inspiration, and concludes by identifying castaway surgeon Henry Pitman as the most likely. An employee of the Duke of Monmouth, Pitman played a part in the Monmouth Rebellion. His short book about his desperate escape from a Caribbean penal colony, followed by his shipwrecking and subsequent desert island misadventures, was published by J. Taylor of Paternoster Row, London, whose son William Taylor later published Defoe's novel. Severin argues that since Pitman appears to have lived in the lodgings above the father's publishing house and that Defoe himself was a mercer in the area at the time, Defoe may have met Pitman in person and learnt of his experiences first-hand, or possibly through submission of a draft.

Severin also discusses another publicised case of a marooned man named only as Will, of the Miskito people of Central America, who may have led to the depiction of Man Friday.[8]

Interpretations

Despite its complicated narrative style and the absence of the supposedly indispensable love motive, it was received well in the literary world. The book is considered one of the most widely published books in history (behind some of the sacred texts). It has been a hit since the day it was published, and continues to be highly regarded to this day.

Colonial

Novelist James Joyce eloquently noted that the true symbol of the British conquest is Robinson Crusoe: "He is the true prototype of the British colonist. … The whole Anglo-Saxon spirit is in Crusoe: the manly independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow yet efficient intelligence, the sexual apathy, the calculating taciturnity."[9]

In a sense Crusoe attempts to replicate his own society on the island. This is achieved through the application of European technology, agriculture, and even a rudimentary political hierarchy. Several times in the novel Crusoe refers to himself as the 'king' of the island, whilst the captain describes him as the 'governor' to the mutineers. At the very end of the novel the island is explicitly referred to as a 'colony.' The idealized master-servant relationship Defoe depicts between Crusoe and Friday can also be seen in terms of cultural imperialism. Crusoe represents the 'enlightened' European whilst Friday is the 'savage' who can only be redeemed from his supposedly barbarous way of life through the assimilation into Crusoe's culture. Nevertheless, within the novel Defoe also takes the opportunity to criticize the historic Spanish conquest of South America.

Religious

According to J.P. Hunter, Robinson is not a hero, but an everyman. He begins as a wanderer, aimless on a sea he does not understand, and ends as a pilgrim, crossing a final mountain to enter the promised land. The book tells the story of how Robinson becomes closer to God, not through listening to sermons in a church but through spending time alone amongst nature with only a Bible to read.

Robinson Crusoe is filled with religious aspects. Defoe was himself a Puritan moralist, and normally worked in the guide tradition, writing books on how to be a good Puritan Christian, such as The New Family Instructor (1728) and Religious Courtship (1732). While Robinson Crusoe is far more than a guide, it shares many of the same themes and theological and moral points of view. The very name "Crusoe" may have been taken from Timothy Cruso, a classmate of Defoe's who had written guide books himself, including God the Guide of Youth (1685), before dying at an early age — just eight years before Defoe wrote Robinson Crusoe. Cruso would still have been remembered by contemporaries and the association with guide books is clear. It has even been suggested that God the Guide of Youth inspired Robinson Crusoe because of a number of passages in that work that are closely tied to the novel; however this is speculative.[10]

The Biblical story of Jonah is alluded to in the first part of novel. Like Jonah, Crusoe neglects his 'duty' and is punished at sea.

A central concern of Defoe's in the novel is the Christian notion of Providence. Crusoe often feels himself guided by a divinely ordained fate, thus explaining his robust optimism in the face of apparent hopelessness. His various fortunate intuitions are taken as evidence of a benign spirit world. Defoe also foregrounds this theme by arranging highly significant events in the novel to occur on Crusoe's birthday.

Moral

When confronted with the cannibals, Crusoe wrestles with the problem of cultural relativism. Despite his disgust, he feels unjustified in holding the natives morally responsible for a practice so deeply ingrained in their culture. Nevertheless he retains his belief in an absolute standard of morality; he condemns cannibalism as a 'national crime' and forbids Friday from practising it. Modern readers may also note that despite Crusoe's apparently superior morality, in common with the culture of his day, he accepts slavery as a basic feature of colonial life.

Economic

In classical and neoclassical economics, Crusoe is regularly used to illustrate the theory of production and choice in the absence of trade, money and prices.[11] Crusoe must allocate effort between production and leisure, and must choose between alternative production possibilities to meet his needs. The arrival of Friday is then used to illustrate the possibility of, and gains from, trade.

The classical treatment of the Crusoe economy has been discussed and criticised from a variety of perspectives.

Karl Marx made an analysis of Crusoe in his classic work Capital. In Marxist terms, Crusoe's experiences on the island represents the inherent economic value of labour over capital. Crusoe frequently observes that the money he salvaged from the ship is worthless on the island, especially when compared to his tools.

For the literary critic Angus Ross, Defoe's point is that money has no intrinsic value and is only valuable insofar as it can be used in trade. There is also a notable correlation between Crusoe's spiritual and financial development as the novel progresses, possibly signifying Defoe's belief in the Protestant work ethic.

The Crusoe model has also been assessed from the perspectives of feminism [12] and Austrian economics [13]

Cultural influences

The book proved so popular that the names of the two main protagonists have entered the language. The term "Robinson Crusoe" is virtually synonymous with the word "castaway" and is often used as a metaphor for being or doing something alone. Robinson Crusoe usually referred to his servant as "my man Friday", from which the term "Man Friday" (or "Girl Friday") originated, referring to a dedicated personal assistant, servant, or companion.

The success of the book spawned many imitators, and castaway novels became quite popular in Europe in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Most of these have fallen into obscurity, but some became established in their own right, including The Swiss Family Robinson.

In Jean-Jacques Rousseau's treatise on education, Emile: Or, On Education, the one book the main character, Emile, is allowed to read before the age of twelve is Robinson Crusoe. Rousseau wants Emile to identify himself as Crusoe so he could rely upon himself for all of his needs. In Rousseau's view, Emile needs to imitate Crusoe's experience, allowing necessity to determine what is to be learned and accomplished. This is one of the main themes of Rousseau's educational model.

In Wilkie Collins's most popular novel, The Moonstone, one of the chief characters and narrators, Gabriel Betteredge, places implicit faith in all that Robinson Crusoe says, and uses the book for a sort of divination. He considers 'The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe' the finest book ever written, and considers a man but poorly read if he had happened not to read the book.

Nobel Prize-winning (2003) author J. M. Coetzee in 1986 published a novel entitled Foe, in which he explores an alternative telling of the Crusoe story, an allegorical story about racism, philosophy, and colonialism.

In Kenneth Gardner's award winning 2002 novel, Rich Man's Coffin, he portrays the true story of a black American slave who escapes on a whaling ship to New Zealand to become chief of one of the cannibal Maori tribes. This is a reversal of racial roles, with the black man taking the lead role of the Robinson Crusoe figure.

Jacques Offenbach wrote an opéra comique called Robinson Crusoé which was first performed at the Opéra-Comique, Salle Favart on 23 November 1867. This was based on the British pantomime version rather than the novel itself. The libretto was by Eugène Cormon and Hector-Jonathan Crémieux. The opera includes a duet by Robinson Crusoe and Friday.

French novelist Michel Tournier wrote Friday ( French Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique) published in 1967. His novel explores themes including civilization versus nature, the psychology of solitude, as well as death and sexuality, in a retelling of Defoe's Robinson Crusoe story. Tournier's Robinson chooses to remain on the island, rejecting civilization when offered the chance to escape 28 years after being shipwrecked.

Editions

- Robinson Crusoe, Oneworld Classics 2008. ISBN 978-1-94749-012-4

- Robinson Crusoe, Penguin Classics 2003. ISBN 978-0141439822

- Robinson Crusoe, Oxford World's Classics 2007. ISBN 978-0192833426

- Robinson Crusoe, "Planet PDF Free to Download E-Book". Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

Adaptions

- Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, a Sailor from York (1982) - Czechoslovakian animated film

- The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (TV series) (1964) - French TV-series

- Crusoe (TV series) (2008) - American TV-series

See also

- Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

- Robinsonade

- Man Friday

- Castaway

- Self-sufficiency

- Homo economicus

- The Swiss Family Robinson

- Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N.

- Robinson Crusoe on Mars

- Cast Away

- Rich Man's Coffin

- Gilligan's Island (TV series)

- Journal of an Urban Robinson Crusoe

- The Coral Island

- Lost (TV series)

Notes

- ↑ Robinson Crusoe, Chapter 23.

- ↑ Nawal Muhammad Hassan (1980), Hayy bin Yaqzan and Robinson Crusoe: A study of an early Arabic impact on English literature, Al-Rashid House for Publication.

- ↑ Cyril Glasse (2001), New Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 202, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0759101906.

- ↑ Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", Journal of Religion and Health 43 (4): 357-377 [369].

- ↑ Martin Wainwright, Desert island scripts, The Guardian, 22 March 2003.

- ↑ see Alan Filreis

- ↑ Ian Watt. "Robinson Crusoe as a Myth", from Essays in Criticism (April 1951). Reprinted in the Norton Critical Edition (second edition, 1994) of Robinson Crusoe.

- ↑ William Dampier, A New Voyage round the World, 1697 [1].

- ↑ James Joyce, “Daniel Defoe,” translated from Italian manuscript and edited by Joseph Prescott, Buffalo Studies 1 (1964): 24-25

- ↑ Hunter, J. Paul (1968) The Reluctant Pilgrim. As found in Norton Critical Edition (see References).

- ↑ Varian, Hal R. (1990). Intermediate microeconomics: a modern approach. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-95924-4.

- ↑ "Robinson Crusoe: The quintessential economic man? - Feminist Economics".

- ↑ Murray Rothbard, The Ethics of Liberty, 1982, Chapter 6 [2].

References

- Shinagel, Michael, ed. (1994). Robinson Crusoe. Norton Critical Edition. ISBN 0-393-96452-3. Includes textual annotations, contemporary and modern criticisms, bibliography.

- Ross, Angus, ed. (1965) Robinson Crusoe. Penguin.

External links

- Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

- “2008 edition of Robinson Crusoe”, with a 1719 “map by W. Taylor” and illustrations by W. Mears & T. Woodward in 1726, “John Ward Dunsmore” in 1903 and “Christopher Williams” in 1903.

- Robinson Crusoe (London: W. Taylor, 1719)., commented text of the first edition, free at Editions Marteau.

- Free eBook of Robinson Crusoe RSS version.

- Free eBook of Robinson Crusoe with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth

- Free audiobook of Robinson Crusoe from Librivox

- Robinson Crusoe, told in words of one syllable, by Lucy Aikin (aka "Mary Godolphin") (1723-1764).

- http://www.digbib.org/Daniel_Defoe_1661/The_Further_Adventures_Of_Robinson_Crusoe The text of volume II.

- Chasing Crusoe, multimedia documentary explores the novel and real life history of Selkirk.

- Robinson Crusoe on Literapedia