Richard III (play)

Richard III is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in approximately 1591, depicting the Machiavellian rise to power and subsequent short reign of Richard III of England.[1]The play is grouped among the histories in the First Folio and is most often classified as such. Occasionally, however, as in the quarto edition, it is termed a tragedy. Richard III concludes Shakespeare's first tetralogy (also containing Henry VI parts 1-3). After Hamlet, it is the second longest play in the canon and is the longest of the First Folio, whose version of Hamlet is shorter than its Quarto counterpart. The play is rarely performed unabridged; often certain peripheral characters are removed entirely, most commonly Margaret. In such instances extra lines are often invented or added from elsewhere in the sequence in order to establish the nature of characters' relationships.

A further reason for abridgment is that Shakespeare assumed that his audiences would be familiar with the Henry VI plays, and frequently made indirect references to events in them, such as Richard's murder of Henry VI or the defeat of Henry's queen Margaret.

Contents |

Sources

Shakespeare's primary source for Richard III, as with most of his history plays, was Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles; the publication date of the second edition, 1587, being the terminus post quem for the play. It is also likely that Shakespeare consulted Edward Hall's The Union of the Two Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York (second edition, 1548).

Date and text

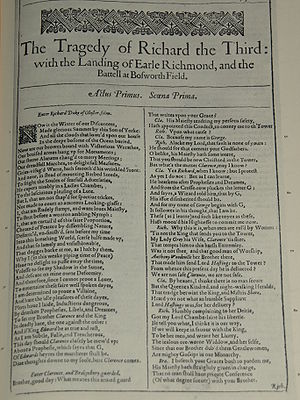

Richard III is believed to be one of Shakespeare's earliest plays, preceded only by the three parts of Henry VI and perhaps a handful of comedies. It is believed to have been written circa 1591. Although Richard III was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on October 20, 1597 by the bookseller Andrew Wise, who published the first quarto (Q1) later that year (with printing done by Valentine Simmes), Marlowe's Edward II, which cannot have been written much later than 1592 (Marlowe died in 1593) is thought to have been influenced by it. A second quarto (Q2) followed in 1597, printed by Thomas Creede for Andrew Wise, containing an attribution to Shakespeare on its title page and may have been a memorial reconstruction.[2] Q3 appeared in 1602, Q4 in 1605, Q5 in 1612, and Q6 in 1622; the frequency attesting to its popularity. The First Folio version followed in 1623.

Performance

The earliest certain performance occurred on Saturday, 17 November, 1633, when Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria watched it on the Queen's birthday. Yet plainly it had been performed many times before that. The Diary of Philip Henslowe records a popular play he calls Buckingham, performed in Dec. 1593 and Jan. 1594, which might have been Shakespeare's play.

Colley Cibber produced the most successful of the Restoration adaptations of Shakepeare with his version of Richard III, at Drury Lane starting in 1700. Cibber himself played the role till 1739, and his version was on stage for the next century and a half. It contained the immortal line "Off with his head; so much for Buckingham" — possibly the most famous Shakespearean line that Shakespeare didn't write. The original Shakespearean version returned in a production at Sadler's Wells Theatre in 1845.[3]

Characters

(Note: Links are to articles on the actual historical personages, who may not entirely correspond to Shakespeare's portrayal of them — particularly with respect to the title character, Richard III.)

- King Edward IV

- Edward, Prince of Wales, afterwards Edward V, son to the king

- Richard, Duke of York, son to the king

- George, Duke of Clarence, brother to the king

- Richard, Duke of Gloucester, afterwards King Richard III, brother to the king

- Edward, Earl of Warwick, young son of Clarence

- Henry, Earl of Richmond, afterwards King Henry VII

- Thomas Cardinal Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Thomas Rotherham, Archbishop of York

- John Morton, Bishop of Ely

- Duke of Buckingham (Henry Stafford)

- Duke of Norfolk (John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk)

- Earl of Surrey, his son (Thomas Howard)

- Earl Rivers (Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers), brother to Queen Elizabeth

- Marquess of Dorset (Thomas Grey, 1st Marquess of Dorset), son to Queen Elizabeth

- Lord Richard Grey, son to Queen Elizabeth

- Earl of Oxford (John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford)

- Lord Hastings (William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings)

- Lord Stanley (Thomas Stanley), afterwards Earl of Derby

- Lord Lovel (Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell)

- Sir Thomas Vaughan

- Sir Richard Ratcliffe

- Sir William Catesby

- Sir James Tyrrel

- Sir James Blunt (James Blount)

- Sir Walter Herbert

- Sir William Brandon

- Sir Robert Brackenbury, Lieutenant of the Tower

- Christopher Urswick, a priest

- Another priest (Ralph Shaa)

- Hastings, a pursivant

- Tressel and Berkeley, gentlemen attending on the Lady Anne

- Keeper in the Tower

- Lord Mayor of London (Sir Edmund Shaa)

- Sheriff of Wiltshire (Henry Long)

- Elizabeth Woodville, Queen to Edward IV

- Margaret of Anjou, widow of Henry VI

- Duchess of York (Cecily Neville), mother to King Edward IV, Clarence, and Gloucester

- Lady Anne Neville, widow of Edward, Prince of Wales (son of Henry VI), afterwards married to Gloucester

- Margaret Plantagenet, Countess of Salisbury, young daughter of Clarence

- ghosts, lords, gentlemen, citizens, etc.

Synopsis

The play begins with Richard describing the accession to the throne of his brother, King Edward IV of England, eldest son of the late Richard, Duke of York.

- Now is the winter of our discontent

- made glorious summer by this son (or sun) of York (may refer to the symbol of Richard of York)

The speech reveals Richard's jealousy and ambition, as his brother, King Edward the Fourth rules the country successfully. Richard is an ugly hunchback, describing himself as "rudely stamp'd" and "deformed, unfinish'd", who cannot "strut before a wanton ambling nymph." He responds to the anguish of his condition with an outcast's credo: "I am determined to prove a villain / And hate the idle pleasures of these days." Richard plots to have his brother Clarence, who stands before him in the line of succession, conducted to the Tower of London over a prophecy that "G of Edward's heirs the murderer shall be" - which the king interprets as referring to George of Clarence (although the audience later realise that it was actually a reference to Richard of Gloucester).

Richard next ingratiates himself with "the Lady Anne" -- Anne Neville, widow of the Lancastrian Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales. Richard confides to the audience:

"I'll marry Warwick's youngest daughter.

What, though I kill'd her husband and his father?"

Despite her prejudice against him, Anne is won over by his pleas and agrees to marry him. This episode illustrates Richard's supreme skill in the art of insincere flattery.

The atmosphere at court is poisonous: the established nobles are at odds with the upwardly-mobile relatives of Queen Elizabeth, a hostility fueled by Richard's machinations. Queen Margaret, Henry VI's widow, returns in defiance of her banishment and warns the squabbling nobles about Richard. The nobles, all Yorkists, reflexively unite against this last Lancastrian, and the warning falls on deaf ears.

Richard orders two murderers to kill his brother Clarence in the tower. Clarence, meanwhile, relates a dream to his keeper. The dream includes extremely visual language describing Clarence falling from an imaginary ship as a result of Gloucester, who had fallen from the hatches, striking him. Under the water Clarence sees the skeletons of thousands of men "that fishes gnawed upon." He also sees "wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl, inestimable stones, unvalued jewels." All of these are "scatterd in the bottom of the sea." Clarence adds that some of the jewels were in the skulls of the dead. Clarence then imagines dying and being tormented by the ghosts of his father-in-law (Warwick, Anne's father) and brother-in-law (Edward, Anne's former husband) in a hellish afterlife.

After Clarence falls asleep, Brakenbury, Lieutenant of the Tower of London, enters and observes that between the titles of princes and the low names of commoners there is nothing different but the "outward fame," meaning that they both have "inward toil" whether rich or poor. When the murderers arrive, he reads their warrant (which is falsely portrayed as being from the king), and exits with the Keeper, who disobeys Clarence's request to stand by him, and leaves the two murderers the keys.

Clarence wakes and pleads with the murderers, saying that men have no right to obey other men's requests for murder, because all men are under the rule of God not to commit murder. The murderers imply Clarence is a hypocrite because he "unripdst the bowels of (his) sovereign's son (Edward) whom (he was) sworn to cherish and defend." Tactically trying to win them over, he tells them to go to his brother Gloucester who will reward them better for his life than "Edward will for tidings of (his) death." One murderer insists Gloucester himself sent them to perform the bloody act, but Clarence does not believe this. He recalls the unity of Richard Duke of York blessing his three sons with his victorious arm, bidding his brother Gloucester to "think on this and he will weep." Sardonically, a murderer says Gloucester weeps millstones -- echoing Richard's earlier comment about the murderers' own eyes weeping millstones rather than foolish tears (Act I, Sc. 3).

Next, one of the murderers explains that his brother Gloucester hates him, and sent them to the Tower to perform the foul act. Eventually, the murderer with a conscience does not participate in the act, but the other killer stabs Clarence and drowns him in "the Malmsey butt within". The first act closes with the perpetrator needing to find a hole to bury Clarence.

Edward IV, weakened by a reign dominated by physical excess, soon dies, leaving as Protector his brother Richard, who sets about removing the final obstacles to his accession. He meets his nephew, the young Edward V, who is en route to London for his coronation accompanied by relatives of Edward's widow. These Richard arrests and (eventually) beheads, and the young prince and his brother are coaxed into an extended stay at the Tower of London.

Assisted by his cousin Buckingham (Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham), Richard mounts a campaign to present himself as a preferable candidate to the throne, appearing as a modest, devout man with no pretensions to greatness. Lord Hastings, who objects to Richard's ascension, is arrested and executed on a trumped-up charge. Together, Richard and Buckingham spread the rumor that Edward's two sons are illegitimate, and therefore have no rightful claim to the throne. The other lords are cajoled into accepting Richard as king, in spite of the continued survival of his nephews (the Princes in the Tower).

His new status leaves Richard sufficiently confident to dispose of his nephews. Richard asks Buckingham to secure the death of the princes, but Buckingham hesitates. Richard then recruits James Tyrell for this act, which Tyrell causes to be executed. In the meantime, Richard turns against Buckingham for the latter's refusal to kill the princes, and denies Buckingham the prior-promised land grant. At this, Buckingham turns against Richard and defects to the side of the Earl of Richmond, who is currently in exile. Richard tries his old dissembling to get into princess Elizabeth's "nest of spicery", but her mother is not taken in by his eloquence.

In due course, the increasingly paranoid Richard loses what popularity he had. He soon faces rebellions led first by Buckingham and subsequently by the invading Earl of Richmond (Henry VII of England). Buckingham is captured and executed. Both sides arrive for a final battle at Bosworth Field. Prior to the battle, Richard is visited by the ghosts of those whose deaths he has caused, all of whom tell him to Despair and die!. He awakes screaming for 'Jesu' (Jesus) to help him, slowly realizing that he is all alone in the world and that even he hates himself. Richard's language and undertones of self-remorse seem to indicate that, in the final hour, he is repentant for his evil deeds; however, it is too late.

At the battle of Bosworth Field, Lord Stanley (who is also Richmond's stepfather) and his followers desert Richard's side, whereupon Richard calls for the execution of George Stanley, Lord Stanley's son. This does not happen, as the battle is in full swing, and Richard is left at a disadvantage. Richard is soon unhorsed on the field at the climax of the battle, and utters the often-quoted line, A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse! Richmond kills Richard in the final duel. Subsequently, Richmond succeeds to the throne as Henry VII, and marries Elizabeth from the House of York, effectively ending the War of the Roses.

In dramatic terms, perhaps the most important (and, arguably, the most entertaining) feature of the play is the sudden alteration in Richard's character. For the first 'half' of the play, we see him as something of an anti-hero, causing mayhem and enjoying himself hugely in the process:

- I do mistake my person all this while;

- Upon my life, she finds, although I cannot,

- Myself to be a marvellous proper man.

- I'll be at charges for a looking-glass;

Almost immediately after he is crowned, however, his personality and actions take a darker turn. He turns against loyal Buckingham ("I am not in the giving vein"), he falls prey to self-doubt ("I am in so far in blood, that sin will pluck on sin;"); now he sees shadows where none exist and visions of his doom to come ("Despair & die").

Themes and motifs

Comedic elements

The play resolutely avoids demonstrations of physical violence; only Clarence and Richard III die on-stage, while the rest (the two princes, Hastings, Grey, Vaughan, Rivers, Anne, Buckingham, and King Edward) all meet their ends off-stage. Despite the villainous nature of the title character and the grim storyline, Shakespeare infuses the action with comic material, as he does with most of his tragedies. Much of the humour rises from the dichotomy between what we know Richard's character to be and how Richard tries to appear. The prime example is perhaps the portion of Act III, Scene 1, where Richard is forced to "play nice" with the young and mocking Duke of York. Other examples appear in Richard's attempts at acting, first in the matter of justifying Hastings' death and later in his coy response to being offered the crown.

Richard himself also provides some dry remarks in evaluating the situation, as when he plans to marry the Queen Elizabeth's daughter: "Murder her brothers, then marry her; Uncertain way of gain...." Other examples of humor in this play include Clarence's ham-fisted and half-hearted murderers, and the Duke of Buckingham's report on his attempt to persuade the Londoners to accept Richard ("...I bid them that did love their country's good cry, God save Richard, England's royal king!" Richard: "And did they so?" Buckingham: "No, so God help me, they spake not a word....") Puns, a Shakespearean staple, are especially well-represented in the scene where Richard tries to persuade Queen Elizabeth to woo her daughter on his behalf.

Free will and fatalism

One of the central themes of Richard III is the idea of fate, especially as it is seen through the tension between free will and fatalism in the actions and speech of the villain-hero, Richard, as well as the reactions to him by other characters. There is no doubt that Shakespeare drew heavily from Sir Thomas More’s account of Richard III as a criminal and tyrant as inspiration for his own rendering. This influence, especially as it relates to the role of divine punishment in Richard’s rule of England, reaches its height in the voice of Margaret. As Janis Lull, a noted Shakespeare scholar from the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, suggests, “Margaret gives voice to the belief, encouraged by the growing Calvinism of the Elizabethan era, that individual historical events are determined by God, who often punishes evil with (apparent) evil”.[4]

Thus, it seems possible that Shakespeare, in conforming to the growing “Tudor Myth” of the day, as well as taking into account new theologies of divine action and human will becoming popular in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, sought to paint Richard as the final curse of God on England in punishment for the deposition of Richard II in 1399.[4] The late Irving Ribner, former chair of the English department at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, argued that “…the evil path of Richard is a cleansing operation which roots evil out of society and restores the world at last to the God-ordained goodness embodied in the new rule of Henry VII”.[5]

Victor Kiernan, a Marxist scholar and historian, writes that this interpretation is a perfect fit with the English social perspective of Shakespeare’s day: “An extension is in progress of a privileged class’s assurance of preferential treatment in the next world as in this, to a favoured nation’s conviction of having God on its side, of Englishmen being…the new Chosen People”. [6] As Elizabethan England was slowly colonizing the world, the populace embraced the view of its own Divine Right and Appointment to do so, much as Richard does in Shakespeare’s play.

However, historical fatalism is merely one side of the argument of fate against free will. It is also possible that Shakespeare intended to portray Richard as “…a personification of the Machiavellian view of history as power politics”.[4] In this view, Richard is acting entirely out of his own free will in brutally taking hold of the English throne. Kiernan also presents this side of the coin, noting that “He [Richard] boasts to us of his finesse in dissembling and deception with bits of Scripture to cloak his ‘naked villainy’ (I.iii.334-8)…Machiavelli, as Shakespeare may want us to realize, is not a safe guide to practical politics…”[6]

Kiernan suggests that Richard is merely acting as if God is determining his every step in a sort of Machiavellian manipulation of religion as an attempt to circumvent the moral conscience of those around him. Therefore, historical determinism is merely an illusion perpetrated by Richard’s assertion of his own free will. The Machiavellian reading of the play finds its most convincing evidence in Richard’s interactions with the audience, as when he mentions that he is “determinèd to prove a villain” (I.i.30). However, though it seems Richard views himself as completely in control, Lull suggests that Shakespeare is using Richard to state “the tragic conception of the play in a joke. His primary meaning is that he controls his own destiny. His pun also has a second, contradictory meaning – that his villainy is predestined – and the strong providentialism of the play ultimately endorses this meaning”.[4]

Literary critic Paul Haeffner writes that Shakespeare had a great understanding of language and the potential of every word he used.[7] One word that Shakespeare gave potential to was "joy." This is employed in ACT I, SCENE III, where it is used to show “deliberate emotional effect”.[7] Another word that Haeffner points out is "kind". He makes the suggestion that the word "kind" is used with two different definitions.

The first definition is used to express a “gentle and loving” being, which Clarence uses to describe his brother Richard to the murderers that were sent to kill him. This first definition is, of course, not true in the case of Richard. He hides under that definition of kind to achieve his desire to be king. The second definition concerns “the person’s true nature ... Richard will indeed use Hastings kindly – that is, just as he is in the habit of using people – brutally”.[7] In several cases, Richard does use people as a habit. His first victim was Clarence and then it was Lady Anne. If Richard had married Elizabeth, he would also make sure that he uses her properly as he would kindly do.

Haeffner also writes about how speech is written. He compares the speeches of Richmond and Richard to their soldiers. He describes Richmond’s speech as “dignified” and formal, while Richard’s speech is explained as “slangy and impetuous”.[7] Richard’s casualness in speech is also noted by another writer. However, Lull does not make the comparison between Richmond and Richard as Haeffner did, but between Richard and the women of Richard III. However, it is important to note that the women share the formal language that Richmond uses. She makes the argument that the difference in speech “reinforces the thematic division between the women’s identification with the social group and Richard’s individualism”.[8] Haeffner agrees that Richard is “an individualist, hating dignity and formality”.[7]

Janis Lull also takes special notice of the mourning women. She suggests that they are associated with “figures of repetition as anaphora – beginning each clause in a sequence with the same word – and epistrophe – repeating the same word at the end of each clause”.[8] One example of the epistrophe can be found in Margaret’s speech in ACT I, SCENE III. Haeffner refers to these as few of many “devices and tricks of style” that occur in the play, showcasing Shakespeare’s ability to bring out the potential of every word.[7]

Richard as protagonist and antagonist

Richard of Gloucester is an exceptional creation of Shakespeare's in that his character constantly changes and shifts and, in doing so, alters the dramatic structure of of the play.

Richard immediately establishes a connection with the audience with his opening monologue. In the soliloquy he introduces his amorality and Machiavellian nature to the audience and but at the same time treats them as if they were co-conspirators in his plotting; one may well be enamored by his rhetoric whilst being appalled by his scheming. Richard’s wit is exercised with great skill in Act 1, as seen in the impressive interchanges with Lady Anne (Act 1, Scene 2) and his brother Clarence (Act 1, Scene 1). In his dialogues Act 1, Richard knowingly refers to thoughts he has only previously shared with the audience to keep the audience attuned to him and his objectives. In 1.1, Richard tells the audience in a soliloquy how he plans to claw his way to the throne—killing his brother Clarence as a necessary step to get there. However, Richard plays the empathizer with Clarence and falsely reassures him by saying, “I will deliver you, or else lie for you” (1.1.115); which the audience knows—and Richard tells us after Clarence’s exit—that he is not honest with Clarence (versus lying in a cell for him) and will only ruin him [9]. In the beginning Acts of the play, Richard is a character that participates in the world he exists in. Scholar Michael E. Mooney describes Richard as occupying a “figural position”—he is able to move in and out of it by talking with us on one level, and interacting with other characters an another [10]; ably bending the boundaries between worlds.

Each scene in Act 1 is book-ended by Richard directly addressing the audience. This action on Richard’s part not only keeps him in control of the dramatic action of the play, but also of how the audience sees him—in a somewhat positive light, or as the protagonist [11]. Richard actually embodies the dramatic character of ‘Vice’ from Medieval mystery plays—with which Shakespeare was very familiar from his time—with his “impish-to-fiendish humour”. Like Vice, Richard is able to reverse what is ugly and evil—his thoughts and aims, his view of other characters—into what is amiable and amusing for the audience [12].

In the earlier acts of the play, too, the role of the antagonist is filled by that of the old Lancastrian queen, Margaret, who is reviled by the Yorkists and whom Richard verbally manipulates and condemns with ease in Act 1, Scene 3.

However, after Act 1 notably, the number and quality of Richard’s asides to the audience decrease significantly, as well as multiple scenes are interspersed that do not include Richard at all [13], but average Citizens (Act 2, Scene 3), or the Duchess of York and Clarence’s children (Act 2, Scene 2), whose action centres around morality or values—the very things Richard abhors. Without Richard guiding the audience through the dramatic action, we, as the audience, are left evaluate what is going on for ourselves. We begin to contemplate moral ideas juxtaposed with Richard’s behaviour. The function of Richard as the protagonist figure begins to weaken significantly, as does his witty verbal capabilities with other characters. In Act 4, Scene 4, after the murder of the two young princes and the ruthless murder of Lady Anne, the women of the play—Queen Elizabeth, the Duchess of York, and even Margaret—gather to mourn their state and to curse Richard; and it is difficult as the audience not to sympathize with them. When Richard enters to bargain with Queen Elizabeth for the hand of her daughter—a scene whose form echoes the same rhythmically quick dialogue as the Lady Anne scene in Act 1—he has lost his vivacity and playfulness for communication, and it is obvious he is not the same Richard [14].

By the end of Act 4, everyone else in the play—including Richard’s own mother, the Duchess—is against him, he does not interact with the audience nearly as much, and the inspiring quality of his speech has declined into merely giving and requiring information. As Richard gets closer to his illusion of the crown, and finally enters into it by becoming king, he has enclosed himself within the world of the play—no longer embodying his facile movement in and out of the dramatic action, he is now stuck firmly within it [15]. It is from Act 4 that Richard really begins his rapid decline into truly being the antagonist. Acclaimed Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt notes how Richard even refers to himself as “the formal Vice, Iniquity” (3.1.82), which informs the audience that he knows what his function is; but also like Vice in the morality plays, the fates will turn and get Richard in the end, which Elizabethan audiences would have recognized [16].

In addition, the character of Richmond enters into the play in Act 5 to overthrow Richard and save the state from his tyranny—effectively being the instantaneous new protagonist. A clear contrast to Richard’s antagonistically immoral character, which makes the audience see him as such [17].

The effect of Richard’s shifting character is somewhat of a didactic one. Not unlike the morality plays, Richard III includes the audience in immorality and evil personally along with Richard, but by separating him from the audience and turning him into a full antagonist, Shakespeare forces us to reflect on the nature of malevolence, and to shun it, embracing a moralist perspective.

Notable stage performances of Richard III

- Ciarán Hinds

- F. Murray Abraham

- John Barrymore

- Simon Russell Beale

- Junius Brutus Booth

- John Wilkes Booth

- Kenneth Branagh

- Richard Burbage

- Peter Dinklage

- David Garrick

- Ian Holm

- Edmund Kean

- Anton Lesser

- Ian McKellen

- Laurence Olivier

- Al Pacino

- Ian Richardson

- Antony Sher

- Barry Sullivan

- Donald Wolfit

Adaptations and Cultural References

Film versions

The most famous player of the part in recent times was Laurence Olivier in his 1955 film version. His inimitable rendition has been parodied by many comedians including Peter Cook and Peter Sellers. Sellers, who had aspirations to do the role straight, appeared in a 1965 TV special on The Beatles' music by reciting "A Hard Day's Night" in the style of Olivier's Richard III. The first series of the BBC television comedy Blackadder in part parodies the Olivier film, visually (as in the crown motif), Peter Cook's performance as a Richard who is a jolly, loving monarch but nevertheless oddly reminiscent of Olivier's rendition, and by mangling Shakespearean text ("Now is the summer of our sweet content made o'ercast winter by these Tudor clouds...")

More recently, Richard III has been brought to the screen by Sir Ian McKellen (1995) in an abbreviated version, set in a fictional 1930s fascist England, and by Al Pacino in the 1996 documentary, Looking for Richard. In the 1977 film The Goodbye Girl, Richard Dreyfuss' character, an actor, gives a memorable performance as a homosexual Richard due to his director's unconventional interpretation of the play. In 2002 the story of Richard III was re-told in a movie about gang culture called The Street King.

A 2006 film version of Richard III is part of the independent film-noir titled Purgatory, a retelling of three classic Shakespeare tales, including Richard III. The 2008 version, Richard III, stars Scott M. Anderson and David Carradine.

In 1996, a pristine print of Richard III (1912), starring Frederick Warde as Richard III was discovered by a private collector and donated to the American Film Institute. The 55-minute film is considered to be the earliest surviving American feature film.

Cultural references

- The line: "A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!" (1591/2) is the most well-known quote from the play, and it appears in many (often humorous) variations, with "horse" being replaced by another desired object.

- In Jasper Fforde's The Eyre Affair (2001), Richard III has a similar cult status to The Rocky Horror Show.

- Ian Richardson claimed to have based his performance as Francis Urquhart in House of Cards on the character of Richard III. In one scene, Urquhart quotes a line of Richard's - "shine out, fair sun" (Act I, Scene ii, line 276) [1].

- In Spike Jonze's film, Being John Malkovich, Malkovich, playing himself, appears in one scene as Richard III in production for a small theatre company.

- The film Freaked featured obnoxious pretty-boy actor Ricky Coogan, disfigured, performing Richard's opening monologue with subtitles that reduce the text to "I'm ugly. I never get laid".

- In the 1977 Neil Simon film, The Goodbye Girl, Richard Dreyfuss plays an actor who is directed to perform the role of Richard III as a flamboyant homosexual in an unconventional (and unsuccessful) off-off-Broadway production.

- In the BBC series Blackadder, Richard III is played by Peter Cook in an impression of Laurence Olivier, as a kind-hearted, popular monarch accidentally murdered by Edmund the Black Adder (Rowan Atkinson).

- Antony Sher wrote a book, "The Year of the King", in diary form about his preparation and performance of the role (which he played on crutches) at The Royal Shakespeare Company Stratford in 1985.

- Lines from the play have been quoted or misquoted in many contexts, including casual conversations between individuals. While a complete list of everyone who has ever quoted the play is not possible, some noteworthy places in which it is quoted may include:

- In Bleach, by Kubo Tite

- In Christopher Durang's comedy The Actor's Nightmare

- In Digimon Tamers, episode "A Kingdom for a Horse"

- In the BBC show Red Dwarf, in the episode entitled "Marooned" from Series 3

- In the TV show Family Guy, episode The King Is Dead

- In the video game Yu-Gi-Oh! Duelist of the Roses

- The Simpsons ([2F17] Radioactive Man)

- In The Smiths' song "Cemetery Gates", from the 1986 album The Queen Is Dead

- In Laurie R. King's novel, To Play The Fool

- In the CSI: Crime Scene Investigation episode Forever

- In the movie Raging Bull

- In the title of the novel, "The Winter of Our Discontent," by John Steinbeck, 1961.

- In the Mystery Science Theater 3000 episode "Space Mutiny".

- In the movie V for Vendetta

- In the movie Runaway Train (film), as a closing quote

- In Mel Brooks' film, Robin Hood: Men In Tights

Notes and references

- ↑ Baldwin (2000, pp 1-2)

- ↑ British Library

- ↑ Halliday, (1964, pp 102 & 414)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Lull (1999, pp 6–8)

- ↑ Ribner (1999, p 62)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kiernan (1993, pp 111–112)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Haeffner (1966, pp 56–60)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lull (1999, pp 22–23)

- ↑ Mooney p.37

- ↑ Mooney p.33

- ↑ Mooney pp. 32-33

- ↑ Mooney p.38

- ↑ Mooney p.44

- ↑ Mooney pp.32-33

- ↑ Mooney p.47

- ↑ Greenblatt pp.33-34

- ↑ Mooney p.32

- Baldwin, Pat and Baldwin, Tom. 2000 (eds.). Cambridge School Shakespeare: King Richard III Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- British Library Publishing Drama in Early Modern Europe Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- Haeffner, Paul. 1966. Shakespeare: Richard III London: Macmillan.

- Halliday, F.E. 1964. A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964, Baltimore, Penguin.

- Kiernan, Victor. 1993. Shakespeare: Poet and Citizen London: Verso.

- Lull, Janis. 1999 (ed.). The New Cambridge Shakespeare: Richard III Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ribner, Irving. 1999. "Richard III as an English History Play" Critical Essays on Shakespeare's Richard III Ed. Hugh Macrae Richmond. New York.

- Mooney, Michael E. 1990. "Shakespeare's Dramatic Transactions". Duke University press.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 2005. "Will In The World". New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Further reading

- Paul Prescott - Richard III (Shakespeare Handbooks), 2006 (ISBN 9781403941442)

External links

- Richard the Third on Project Gutenberg

- William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of King Richard the third (London: Andrew Wise, 1597) - HTML version of the first edition.

- Full text of Shakespeare's play - annotated with excerpts from the standard biography to provide comparison with the historical Richard III, from the Richard III Society, American Branch.

- Painting of 'David Garrick as Richard III' by William Hogarth at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

- Lesson plans for Richard III at Web English Teacher

- Interactive video interview with Sir Ian McKellen on Shakespeare, Richard III and Richard's opening speech Intended as an introduction to the play for educational use.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||