Republic of Texas

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

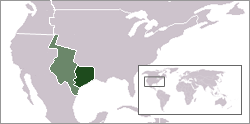

The Republic of Texas was a sovereign nation in North America between the United States and Mexico that existed from 1836 to 1846. Formed as a break-away republic from Mexico by the Texas Revolution, the nation claimed borders that encompassed an area that included all of the present U.S. state of Texas, as well as parts of present-day New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming based upon the Treaties of Velasco between the newly created Texas republic and Mexico. The eastern boundary with the United States was defined by the Adams-Onís Treaty between the United States and Spain, in 1819. Its southern and western-most boundary with Mexico was under dispute throughout the existence of the Republic, with Texas claiming that the boundary was the Rio Grande, and Mexico claiming the Nueces River as the boundary. This dispute would later become a trigger for the Mexican–American War, after the annexation of Texas. Even though Texas was an independent nation, it heavily relied on the United States of America for resources, defense, and finances.

Contents |

Establishment

The Republic of Texas was created from part of the Mexican state Coahuila y Tejas as a result of the Texas Revolution. Mexico was in turmoil as leaders attempted to determine an optimal form of government. In early 1835, as the Mexican government transitioned from a federalist model to centralism, wary colonists in Texas began forming Committees of Correspondence and Safety. A central committee in San Felipe de Austin coordinated their activities.[1] In the Mexican interior, several states revolted against the new centralist policies.[2] The Texas Revolution officially began on October 2, 1835 in the Battle of Gonzales. Although the Texians originally fought for the reinstatement of the Constitution of 1824, by 1836 the aim of the war had changed. The Convention of 1836 declared independence on March 2, 1836 and officially formed the Republic of Texas.

Government

After gaining their independence, the Texas voters had elected a Congress of 14 senators and 29 representatives in September 1836. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas allowed the first president to serve for only two years. It set a three year term for all later presidents.

The first Congress of the Republic of Texas convened in October 1836 at Columbia (now West Columbia). Stephen F. Austin, known as the Father of Texas, died December 27, 1836, after serving two months as Secretary of State for the new Republic. In 1836, five sites served as temporary capitals of Texas (Washington-on-the-Brazos, Harrisburg, Galveston, Velasco and Columbia) before Sam Houston moved the capital to Houston in 1837. In 1839, the capital was moved to the new town of Austin.

The court system inaugurated by Congress included a Supreme Court consisting of a chief justice appointed by the president and four associate justices, elected by a joint ballot of both houses of Congress for four-year terms and eligible for reelection. The associates also presided over four judicial districts. Houston nominated James Collinsworth to be the first chief justice. The county-court system consisted of a chief justice and two associates, chosen by a majority of the justices of the peace in the county. Each county was also to have a sheriff, a coroner, justices of the peace, and constables to serve two-year terms. Congress formed 23 counties, whose boundaries generally coincided with the existing municipalities.

Internal politics of the Republic were based on the conflict between two factions. The nationalist faction, led by Mirabeau B. Lamar, advocated the continued independence of Texas, the expulsion of the Native Americans, and the expansion of Texas to the Pacific Ocean. Their opponents, led by Sam Houston, advocated the annexation of Texas to the United States and peaceful co-existence with Native Americans. The first flag of the republic was the "Burnet Flag" (a gold star on an azure field), followed shortly thereafter by official adoption of the Lone Star Flag. The Republic received diplomatic recognition from the United States, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the Republic of Yucatán.

In London, the original Embassy of the Republic of Texas still stands. Immediately opposite the gates to St. James Palace, Sam Houston's original Embassy of the Republic of Texas to His Majesty's Court is now a hat shop, but is clearly marked with a large plaque.

Diplomatic relations

On March 3, 1837, US President Andrew Jackson appointed Alcée La Branche as chargé d'affaires to the Republic of Texas, thus officially recognizing Texas as an independent republic. France granted official recognition of Texas on September 25, 1839, appointing Alponse Dubois de Saligny to serve as chargé d'affaires. The French Legation still stands in Austin; built in 1841, it is believed by some to be the oldest building in the city.

Great Britain never granted official recognition of Texas due to its own friendly relations with Mexico, but admitted Texan goods into British ports on their own terms.[3]

Statehood

On February 28, 1845, the U.S. Congress passed a bill that would authorize the United States to annex the Republic of Texas. On March 1, U.S. President John Tyler signed the bill. The legislation set the date for annexation for December 29 of the same year. Faced with imminent American annexation of Texas, Charles Elliot and Alphonse de Saligny, the British and French ministers to Texas, were dispatched to Mexico City by their governments. Meeting together with Mexico's foreign secretary, they signed a "Diplomatic Act" in which Mexico offered to recognize an independent Texas, with boundaries that would be determined with French and British mediation. Texas President Anson Jones forwarded both offers to a specially elected convention meeting at Austin, and the American proposal was accepted with only one dissenting vote. The Mexican proposal was never put to a vote. Following the previous decree of President Jones, the proposal was then put to a national vote.

On October 13, 1845 a large majority of voters in the Republic approved both the American offer and the proposed constitution that specifically endorsed slavery and the slave trade. This constitution was later accepted by the U.S. Congress, making Texas a U.S. state on the same day annexation took effect, December 29 1845 (therefore bypassing a territorial phase)[4]. One of the motivations for annexation (besides the primary one of desiring to be united with their perceived Anglo-American ethno-cultural brethren of the United States and their Anglo-American regional-cultural brethren of "the South") was that the Texas government had incurred huge debts which the United States agreed to assume upon annexation. In 1852, in return for this assumption of debt, a large portion of Texas-claimed territory, now parts of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Wyoming, was ceded to the Federal government.

The annexation resolution has been the topic of some historical myths—one that remains is that the resolution granted Texas the explicit right to secede from the Union. This was a right argued by some to be implicitly held by all states at the time, up until the conclusion of the Civil War. The resolution did include two unique provisions: first, it said that up to four additional states could be created from Texas' territory, with the consent of the State of Texas. The resolution did not include any special exceptions to the provisions of the US Constitution regarding statehood. The right to create these possible new states was not "reserved" for Texas, as is sometimes stated.[5]. Second, Texas did not have to surrender its public lands to the federal government. While Texas did cede all territory outside of its current area to the federal government in 1850, it did not cede any public lands within its current boundaries. This means that generally, the only lands owned by the federal government within Texas have actually been purchased by the government. This also means that the state government has control over oil reserves which were later used to fund the state's public university system. In addition, the state's control over offshore oil reserves in Texas runs out to 3 leagues (10.357 miles, 16.668 km) rather than three miles (4.828 km) as with other states[6].

Presidents and vice presidents

| From | To | President | Vice president | Presidential candidates |

Pres. votes |

Vice pres. candidates |

V.P. votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 March 1836 | 22 October 1836 | David G. Burnet (interim) |

Lorenzo de Zavala (interim) |

||||

| 22 October 1836 | 10 December 1838 | Sam Houston | Mirabeau B. Lamar | Sam Houston Henry Smith Stephen F. Austin |

5119 743 587 |

Mirabeau B. Lamar | |

| 10 December 1838 | 13 December 1841 | Mirabeau B. Lamar | David G. Burnet | Mirabeau B. Lamar Robert Wilson |

6995 252 |

David G. Burnet | |

| 13 December 1841 | 9 December 1844 | Sam Houston | Edward Burleson | Sam Houston David G. Burnet |

7915 3619 |

Edward Burleson Memucan Hunt |

6141 4336 |

| 9 December 1844 | 19 February 1846 | Anson Jones | Kenneth L. Anderson | Anson Jones Edward Burleson |

__ __ |

Kenneth L. Anderson |

See also

| History of Texas |

|---|

|

French Texas |

- Timeline of the Republic of Texas

- History of Texas

- The Texas Legation

- The French Legation

Notes

- ↑ Huson (1974), p. 4.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 7.

- ↑ Diplomatic Relations of the Republic of Texas

- ↑ The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: Texas - From Independence to Annexation

- ↑ Joint Resolution for Annexing Texas to the United States

- ↑ Overview of U.S. Legislation and Regulations Affecting Offshore Natural Gas and Oil Activity

References

- Huson, Hobart (1974), Captain Phillip Dimmitt's Commandancy of Goliad, 1835–1836: An Episode of the Mexican Federalist War in Texas, Usually Referred to as the Texian Revolution, Austin, TX: Von Boeckmann-Jones Co.

- Lack, Paul D. (1992), The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and SOcial History 1835–1836, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-497-1

- Republic of Texas Historical Resources

- Republic of Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- The University of Texas/history

- The State of Texas website/history

- Texas: the Rise, Progress, and Prospects of the Republic of Texas, Vol. 1, published 1841, hosted by Portal to Texas History

- Texas: the Rise, Progress, and Prospects of the Republic of Texas, Vol. 2, published 1841, hosted by Portal to Texas History

- Laws of the Republic, 1836-1838 from Gammel's Laws of Texas, Vol. I. hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Laws of the Republic, 1838-1845 from Gammel's Laws of Texas, Vol. II. hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: Texas - From Independence to Annexation

External links

- The Texas Declaration Of Independence TexasBob.com.