Renal cell carcinoma

| Renal cell carcinoma Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

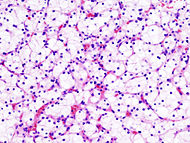

| Histopathologic image of clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Nephrectomy specimen. Hematoxylin-eosin stain. | |

| ICD-10 | C64. |

| ICD-9 | 189.0 |

| ICD-O: | M8312/3 |

| OMIM | 144700 605074 |

| DiseasesDB | 11245 |

| MedlinePlus | 000516 |

| eMedicine | med/2002 |

| MeSH | D002292 |

"Kidney Cancer" redirects here. For Wilms' Tumor/Nephroblastoma, see Wilms' tumor.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC, aka hypernephroma) is the most common form of kidney cancer arising from the proximal renal tubule. It is the most common type of kidney cancer in adults. Initial treatment is most commonly a radical or partial nephrectomy. Where the tumour is confined to the renal parenchyma, the 5-year survival rate is 60-70%, but this is lowered considerably where metastases have spread. It is resistant to radiation therapy and chemotherapy, although some cases respond to immunotherapy. Targeted cancer therapies such as sunitinib have improved the outlook for RCC, although they have not yet demonstrated improved survival.

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

The classic triad is hematuria (blood in the urine), flank pain and an abdominal mass. This is now known as the 'too late triad' because by the time patients present with symptoms, their disease is often advanced beyond a curative stage. In addition, whilst this triad is highly suggestive of RCC, it only occurs in around 15% of the sufferers. Today, the majority of renal tumors are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally on imaging, usually for an unrelated cause.

Signs may include:

- Abnormal urine color (dark, rusty, or brown) due to blood in the urine (found in 60% of cases)

- Loin pain (found in 40% of cases)

- Abdominal mass (25% of cases)

- Malaise, weight loss or anorexia (30% of cases)

- Polycythemia (5% of cases)

- Anaemia resulting from depression of erythropoietin (5% of cases)

- The presenting symptom may be due to metastatic disease, such as a pathologic fracture of the hip due to a metastasis to the bone

- Enlargement of one testicle known as varicocele (usually the left, due to blockage of the left gonadal vein by tumor invasion of the left renal vein -- the right gonadal vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava)

- Vision abnormalities

- Pallor or plethora

- Hirsutism - Excessive hair growth (females)

- Constipation

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) resulting from secretion of renin by the tumour (30% of cases)

- Elevated calcium levels (Hypercalcemia)

- Paraneoplastic disease

Classification

Recent genetic studies have altered the approaches used in classifying renal cell carcinoma. The following system can be used to classify these tumors:[1][2][3]

- Clear cell carcinoma (VHL and others on chromosome 3)

- Papillary carcinoma (MET, PRCC)

- Chromophobe renal carcinoma

- Collecting duct carcinoma

Other associated genes include TRC8, OGG1, HNF1A, HNF1B, TFE3, RCCP3, and RCC17.

Causes

Renal cell carcinoma affects about three in 10,000 people, resulting in about 31,000 new cases in the US per year. Every year, about 12,000 people in the US die from renal cell carcinoma. It is more common in men than women, usually affecting men older than 55.

Kidney cancer both RCC & TCC currently is diagnosed in some 6,600 people in Britain/UK per annum and some 3,600 people who die are recorded as having died of kidney cancer in a given year. The morbidity rate recorded is thought to underestimate the percentage who die of kidney cancer. Often the cause of death recorded on the death certificate may not mention kidney cancer but the subsequent metastases. It is clear that well over 50% of those diagnosed with kidney cancer in Britain will die as a result of the disease.

Why the cells become cancerous is not known. A history of smoking greatly increases the risk for developing renal cell carcinoma. Some people may also have inherited an increased risk to develop renal cell carcinoma, and a family history of kidney cancer increases the risk.

Increasingly there is a belief that inhalation of a diversity of chemicals may be causal and it is also noted that there is a steady increase in diagnosis in women. That a disproportionate percentage of those diagnosed with kidney cancer are obese is increasingly believed to be a significant factor.

People with von Hippel-Lindau disease, a hereditary disease that also affects the capillaries of the brain, commonly also develop renal cell carcinoma, specifically the clear cell type of RCC. Kidney disorders that require dialysis for treatment also increase the risk for developing renal cell carcinoma.

Pathology

Gross examination shows a yellowish, multilobulated tumor in the renal cortex, which frequently contains zones of necrosis, hemorrhage and scarring.

Light microscopy shows tumor cells forming cords, papillae, tubules or nests, and are atypical, polygonal and large. Because these cells accumulate glycogen and lipids, their cytoplasm appear "clear", lipid-laden, the nuclei remain in the middle of the cells, and the cellular membrane is evident. Some cells may be smaller, with eosinophilic cytoplasm, resembling normal tubular cells. The stroma is reduced, but well vascularized. The tumor compresses the surrounding parenchyma, producing a pseudocapsule.[4]

Secretion of vasoactive substances (e.g. renin) may cause arterial hypertension, and release of erythropoietin may cause erythrocytosis (increased production of red blood cells).

Radiology

The characteristic appearance of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a solid renal lesion which disturbs the renal contour. It will frequently have an irregular or lobulated margin. 85% of solid renal masses will be RCC. 10% of RCC will contain calcifications, and some contain macroscopic fat (likely due to invasion and encasement of the perirenal fat). Following intravenous contrast administration (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging), enhancement will be noted, and will increase the conspicuity of the tumor relative to normal renal parenchyma.

A list of solid renal lesions includes:

- renal cell carcinoma

- metastasis from an extra-renal primary neoplasm

- renal lymphoma

- squamous cell carcinoma

- juxtaglomerular tumor (reninoma)

- transitional cell carcinoma

- angiomyolipoma

- oncocytoma

- Wilm's tumor

In particular, reliably distinguishing renal cell carcinoma from an oncocytoma (a benign lesion) is not possible using current medical imaging or percutaneous biopsy.

Renal cell carcinoma may also be cystic. As there are several benign cystic renal lesions (simple renal cyst, hemorrhagic renal cyst, multilocular cystic nephroma, polycystic kidney disease), it may occasionally be difficult for the radiologist to differentiate a benign cystic lesion from a malignant one. A classification system for cystic renal lesions that classifies them based specific imaging features into groups that are benign and those that need surgical resection is available[5]. At diagnosis, 30% of renal cell carcinoma has spread to that kidney's renal vein, and 5-10% has continued on into the inferior vena cava[6].

Percutaneous biopsy can be performed by a radiologist using ultrasound or computed tomography to guide sampling of the tumor for the purpose of diagnosis. However this is not routinely performed because when the typical imaging features of renal cell carcinoma are present, the possibility of an incorrectly negative result together with the risk of a medical complication to the patient make it unfavorable from a risk-benefit perspective.This is not completely accurate, there are new experimental treatments.

Treatment

If it is only in the kidneys, which is about 40% of cases, it can be cured roughly 90% of the time with surgery. If it has spread outside of the kidneys, often into the lymph nodes or the main vein of the kidney, then it must be treated with adjunctive therapy, including cytoreductive surgery

Watchful waiting

Small renal tumors represent the majority of tumors that are treated today by way of partial nephrectomy. The average growth of these masses is about 4-5 mm per year, and a significant proportion (up to 40%) of tumors less than 4cm in diameter are benign. More centers of excellence are incorporating needle biopsy to confirm the presence of malignant histology prior to recommending definitive surgical extirpation. In the elderly, patients with co-morbidities and in poor surgical candidates, small renal tumors may be monitored carefully with serial imaging. Most clinicians conservatively follow tumors up to a size threshold between 3-5 cm, beyond which the risk of distant spread (metastases) is about 5%.

Surgery

Surgical removal of all or part of the kidney (nephrectomy) is recommended. This may include removal of the adrenal gland, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and possibly tissues involved by direct extension (invasion) of the tumor into the surrounding tissues. In cases where the tumor has spread into the renal vein, inferior vena cava, and possibly the right atrium (angioinvasion), this portion of the tumor can be surgically removed, as well. In case of metastases surgical resection of the kidney ("cytoreductive nephrectomy") may improve survival[7], as well as resection of a solitary metastatic lesion.

Percutaneous therapies

Percutaneous, image-guided therapies, usually managed by radiologists, are being offered to patients with localized tumor, but who are not good candidates for a surgical procedure. This sort of procedure involves placing a probe through the skin and into the tumor using real-time imaging of both the probe tip and the tumor by computed tomography, ultrasound, or even magnetic resonance imaging guidance, and then destroying the tumor with heat (radiofrequency ablation) or cold (cryotherapy). These modalities are at a disadvantage compared to traditional surgery in that pathologic confirmation of complete tumor destruction is not possible.

Medications

RCC "elicits an immune response, which occasionally results in dramatic spontaneous remissions." This has encouraged a strategy of using immunomodulating therapies, such as cancer vaccines and interleukin-2 (IL-2), to reproduce this response. IL-2 has produced "durable remissions" in a small number of patients, but with substantial toxicity. Another strategy is to restore the function of the VHL gene, which is to destroy proteins that promote inappropriate vascularization. Bevacizumab, an antibody to VEGF, has significantly prolonged time to progression, but phase 3 trials have not been published. Sunitinib (Sutent), sorafenib (Nexavar), and temsirolimus, which are small-molecule inhibitors of proteins, have been approved by the U.S. F.D.A.[8]

Sorafenib was FDA approved in December 2005 for treatment of advanced renal cell cancer, the first receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor indicated for this use.

A month later, Sunitinib was approved as well. Sunitinib—an oral, small-molecule, multi-targeted (RTK) inhibitor—and sorafenib both interfere with tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis as well as tumor cell proliferation. Sunitinib appears to offer greater potency against advanced RCC, perhaps because it inhibits more receptors than sorafenib. However, these agents have not been directly compared against one another in a single trial. [1][2]

Recently the first Phase III study comparing an RTKI with cytokine therapy was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. This study showed that Sunitinib offered superior efficacy compared with interferon-α. Progression-free survival (primary endpoint) was more than doubled. The benefit for sunitinib was significant across all major patient subgroups, including those with a poor prognosis at baseline. 28% of sunitinib patients had significant tumor shrinkage compared with only 5% of patients who received interferon-α. Although overall survival data are not yet mature, there is a clear trend toward improved survival with sunitinib. Patients receiving sunitinib also reported a significantly better quality of life than those treated with IFNa. [9] Based on these results, lead investigator Dr. Robert Motzer announced at ASCO 2006 that “Sunitinib is the new reference standard for the first-line treatment of mRCC.” [10]

Temsirolimus (CCI-779) is an inhibitor of mTOR kinase (mamallian target of rapamycin) that was shown to prolong overall survival vs. interferon-α in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma with three or more poor prognostic features. The results of this Phase III randomized study were presented at the 2006 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (www.ASCO.org).

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy may be used in some cases, but cure is unlikely unless all the cancer can be removed with surgery. The use of Tyrosine Kinase (TK) inhibitors, such as Sunitinib and Sorafenib, and Temsirolimus are described in a different section.

Vaccine

Cancer vaccines, such as TroVax, are in phase 3 trials for treatment of renal cell carcinoma.[11]

Cryoablation

This involves destroying the kidney tumor without surgery, by freezing the tumor. The process can remove 95% of tumors in one treatment and can be tolerated by patients who are not good candidates for surgery (older or weak patients). [12].

The outcome varies depending on the size of the tumor, whether it is confined to the kidney or not, and the presence or absence of metastatic spread. The Fuhrman grading, which measures the aggressiveness of the tumor, may also affect survival, though the data is not as strong to support this.

The five year survival rate is around 90-95% for tumors less than 4 cm. For larger tumors confined to the kidney without venous invasion, survival is still relatively good at 80-85%. For tumors that extend through the renal capsule and out of the local fascial investments, the survivability reduces to near 60%. If it has metastasized to the lymph nodes, the 5-year survival is around 5 % to 15 %. If it has spread metastatically to other organs, the 5-year survival rate is less than 5 %.

For those that have tumor recurrence after surgery, the prognosis is generally poor. Renal cell carcinoma does not generally respond to chemotherapy or radiation. Immunotherapy, which attempts to induce the body to attack the remaining cancer cells, has shown promise. Recent trials are testing newer agents, though the current complete remission rate with these approaches are still low, around 12-20% in most series.

See also

- Stauffer syndrome

References

- ↑ Reuter VE, Presti JC (April 2000). "Contemporary approach to the classification of renal epithelial tumors". Semin. Oncol. 27 (2): 124–37. PMID 10768592.

- ↑ Bodmer D, van den Hurk W, van Groningen JJ, et al (October 2002). "Understanding familial and non-familial renal cell cancer". Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 (20): 2489–98. PMID 12351585. http://hmg.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12351585.

- ↑ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 1016. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ↑ "pathologyatlas.ro". Retrieved on 2007-12-29.

- ↑ Israel GM, Bosniak MA (August 2005). "How I do it: evaluating renal masses". Radiology 236 (2): 441–50. doi:. PMID 16040900.

- ↑ Oto A, Herts BR, Remer EM, Novick AC (December 1998). "Inferior vena cava tumor thrombus in renal cell carcinoma: staging by MR imaging and impact on surgical treatment". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 171 (6): 1619–24. PMID 9843299. http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9843299.

- ↑ Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, Tangen C, Van Poppel H, Crawford ED (March 2004). "Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis". J Urol. 171 (3): 1071–6. doi:. PMID 14767273.

- ↑ Michaelson MD, Iliopoulos O, McDermott DF, McGovern FJ, Harisinghani MG, Oliva E (May 2008). "Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 17-2008. A 63-year-old man with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma". N Engl J Med. 358 (22): 2389–96. doi:. PMID 18509125. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/358/22/2389.

- ↑ Motzer RJ et al. (2007). "Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma". N Engl J Med 356 (2): 115–124. doi:. PMID 17215529.

- ↑ Motzer RJ et al.. "Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Sunitinib malate (SU11248) versus Interferon-alfa as First-line Systemic Therapy for Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma". ASCO 2006.

- ↑ Vaccine for kidney and bowel cancers 'within three years' | Mail Online

- ↑ <http://www.yourcancertoday.com/news/drnakada.html" title=" Dr. Nakada, on Your Cancer Today

External links

- Photo at: Atlas of Pathology

- www.411cancer.com - General Cancer Information

- Vaccine for kidney cancer

- Offers a massive aggregation of media articles and data collated by patients for patients & Forum for patients and carers

- Renal Cell Carcinoma (translocation associated) — ArQule Clinical Research Study

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||