Rate of return

In finance, rate of return (ROR), also known as return on investment (ROI), rate of profit or sometimes just return, is the ratio of money gained or lost (realized or unrealized) on an investment relative to the amount of money invested. The amount of money gained or lost may be referred to as interest, profit/loss, gain/loss, or net income/loss. The money invested may be referred to as the asset, capital, principal, or the cost basis of the investment. ROI is usually expressed as a percentage rather than a fraction.

ROI does not indicate how long an investment is held. However, ROI is most often stated as an annual or annualized rate of return, and it is most often stated for a calendar or fiscal year. In this article, "ROI" indicates an annual or annualized rate of return, unless otherwise noted.

ROI is used to compare returns on investments where the money gained or lost — or the money invested — are not easily compared using monetary values. For instance, a $1,000 investment that earns $50 in interest generates more cash than a $100 investment that earns $20 in interest, but the $100 investment earns a higher return on investment.

- $50/$1,000 = 5% ROI

- $20/$100 = 20% ROI

When considering a continuous process of gaining or losing money with a constant rate of return, the annual rate of return is any value greater than -100%; a positive percentage corresponds to exponential growth of the capital, a value between -100% and 0% exponential decay.

Contents |

Calculation

The initial value of an investment,  , does not always have a clearly defined monetary value, but for purposes of measuring ROI, the initial value must be clearly stated along with the rationale for this initial value. The final value of an investment,

, does not always have a clearly defined monetary value, but for purposes of measuring ROI, the initial value must be clearly stated along with the rationale for this initial value. The final value of an investment,  , also does not always have a clearly defined monetary value, but for purposes of measuring ROI, the final value must be clearly stated along with the rationale for this final value.

, also does not always have a clearly defined monetary value, but for purposes of measuring ROI, the final value must be clearly stated along with the rationale for this final value.

The rate of return can be calculated over a single period, or expressed as an average over multiple periods.

Single-period

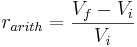

Arithmetic return

The arithmetic return is defined as the following:

If the final investment value excludes capital gains, then  is sometimes referred to as the yield. See also: effective interest rate, effective annual rate (EAR) or annual percentage yield (APY).

is sometimes referred to as the yield. See also: effective interest rate, effective annual rate (EAR) or annual percentage yield (APY).

If the final investment value includes both capital gains and intermediate income such as dividends, then  is the holding period return.

is the holding period return.

Logarithmic or continuously compounded return

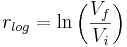

The logarithmic return or continuously compounded return, also known as force of interest, is defined as:

.

.

It is the reciprocal of the e-folding time.

Multiperiod average returns

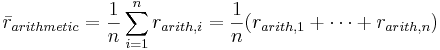

Arithmetic average rate of return

The arithmetic average rate of return over n periods is defined as:

Geometric average rate of return

The geometric average rate of return, also known as the time-weighted rate of return, over n periods is defined as:

The geometric average rate of return calculated over n years is also known as the annualized return.

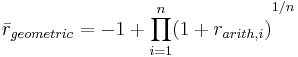

Internal rate of return

The internal rate of return, also known as the dollar-weighted rate of return, is defined as the value(s) of  that satisfies the following equation:

that satisfies the following equation:

where:

- NPV = net present value of the investment

Comparisons between various rates of return

Arithmetic and logarithmic return

For both arithmetic returns and logarithmic returns, an investment is profitable when either  or

or  > 0, and unprofitable when either

> 0, and unprofitable when either  or

or  < 0.

< 0.

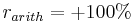

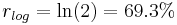

The final value of an investment is twice the initial value when  or

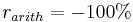

or  . The final value falls to zero, i.e., the initial value can no longer be recovered) when

. The final value falls to zero, i.e., the initial value can no longer be recovered) when  or

or  .

.

Arithmetic and logarithmic returns are not equal, but are approximately equal for small returns. The difference between them is large only when percent changes are high. For example, an arithmetic return of +50% is equivalent to a logarithmic return of 40.55%, while an arithmetic return of -50% is equivalent to a logarithmic return of -69.31%.

Logarithmic returns are often used by academics in their research. The main advantage is that the continuously compounded return is symmetric, while the arithmetic return is not: positive and negative percent arithmetic returns are not equal. This means that an investment of $100 that yields an arithmetic return of 50% followed by an arithmetic return of -50% will result in $75, while an investment of $100 that yields a logarithmic return of 50% followed by an logarithmic return of -50% it will remain $100.

Initial investment,  |

$100 | $100 | $100 | $100 | $100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Final investment,  |

$0 | $50 | $100 | $150 | $200 |

Profit/loss,  |

-$100 | -$50 | $0 | $50 | $100 |

Arithmetic return,  |

-100% | -50% | 0% | 50% | 100% |

Logarithmic return,  |

|

-69.31% | 0% | 40.55% | 69.31% |

Arithmetic average and geometric average rates of return

Both arithmetic and geometric average rates of returns are averages of periodic percentage returns. Neither will accurately translate to the actual dollar amounts gained or lost if percent gains are averaged with percent losses. [1] A 10% loss on a $100 investment is a $10 loss, and a 10% gain on a $100 investment is a $10 gain. When percentage returns on investments are calculated, they are calculated for a period of time – not based on original investment dollars, but based on the dollars in the investment at the beginning and end of the period. So if an investment of $100 loses 10% in the first period, the investment amount is then $90. If the investment then gains 10% in the next period, the investment amount is $99.

A 10% gain followed by a 10% loss is a 1% dollar loss. The order in which the loss and gain occurs does not affect the result. A 50% gain and a 50% loss is a 25% loss. An 80% gain plus an 80% loss is a 64% loss. To recover from a 50% loss, a 100% gain is required. The mathematics of this are beyond the scope of this article, but since investment returns are often published as "average returns", it is important to note that average returns do not always translate into dollar returns.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of Return | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Geometric Average at End of Year | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Capital at End of Year | $105.00 | $110.25 | $115.76 | $121.55 |

| Dollar Profit/(Loss) | $21.55 | |||

| Compound Yield | 5.4% |

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of Return | 50% | -20% | 30% | -40% |

| Geometric Average at End of Year | 50% | 9.5% | 16% | -1.6% |

| Capital at End of Year | $150.00 | $120.00 | $156.00 | $93.60 |

| Dollar Profit/(Loss) | ($6.40) | |||

| Compound Yield | -1.6% |

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of Return | -95% | 0% | 0% | 115% |

| Geometric Average at End of Year | -95% | -77.6% | -63.2% | -42.7% |

| Capital at End of Year | $5.00 | $5.00 | $5.00 | $10.75 |

| Dollar Profit/(Loss) | ($89.25) | |||

| Compound Yield | -22.3% |

Annual returns and annualized returns

Care must be taken not to confuse annual and annualized returns. An annual rate of return is a single-period return, while an annualized rate of return is a multi-period, geometric average return.

An annual rate of return is the return on an investment over a one-year period, such as January 1 through December 31st, or June 3rd 2006 through June 2nd 2007. Each ROI in the cash flow example above is an annual rate of return.

An annualized rate of return is the return on an investment over a period other than one year (such as a month, or two years) multiplied or divided to give a comparable one-year return. For instance, a one-month ROI of 1% could be stated as an annualized rate of return of 12%. Or a two-year ROI of 10% could be stated as an annualized rate of return of 5%.

In the cash flow example below, the dollar returns for the four years add up to $265. The annualized rate of return for the four years is: $265 ÷ ($1,000 x 4 years) = 6.625%.

Uses

- ROI is a measure of cash (or potential cash) generated by an investment, or the cash lost due to the investment. It measures the cash flow or income stream from the investment to the investor. Cash flow to the investor can be in the form of profit, interest, dividends, or capital gain/loss. Capital gain/loss occurs when the market value or resale value of the investment increases or decreases. Cash flow here does not include the return of invested capital.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dollar Return | $100 | $55 | $60 | $50 |

| ROI | 10% | 5.5% | 6% | 5% |

- ROI values typically used for personal financial decisions include Annual Rate of Return and Annualized Rate of Return. For nominal risk investments such as savings accounts or Certificates of Deposit, the personal investor considers the effects of reinvesting/compounding on increasing savings balances over time. For investments in which capital is at risk, such as stock shares, mutual fund shares and home purchases, the personal investor considers the effects of price volatility and capital gain/loss on returns.

- Profitability ratios typically used by financial analysts to compare a company’s profitability over time or compare profitability between companies include Gross Profit Margin, Operating Profit Margin, ROI ratio, Dividend yield, Net profit margin, Return on equity, and Return on assets.[2]

- During capital budgeting, companies compare the rates of return of different projects to select which projects to pursue in order to generate maximum return or wealth for the company's stockholders. Companies do so by considering the average rate of return, payback period, net present value, profitability index, and internal rate of return for various projects. [3]

- A return may be adjusted for taxes to give the after-tax rate of return. This is done in geographical areas or historical times in which taxes consumed or consume a significant portion of profits or income. The after-tax rate of return is calculated by multiplying the rate of return by the tax rate, then subtracting that percentage from the rate of return.

- A return of 5% taxed at 15% gives an after-tax return of 4.25%

-

- 0.05 x 0.15 = 0.0075

- 0.05 - 0.0075 = 0.0425 = 4.25%

- A return of 10% taxed at 25% gives an after-tax return of 7.5%

-

- 0.10 x 0.25 = 0.025

- 0.10 - 0.025 = 0.075 = 7.5%

Investors usually seek a higher rate of return on taxable investment returns than on non-taxable investment returns.

- A return may be adjusted for inflation to better indicate its true value in purchasing power. Any investment with a nominal rate of return less than the annual inflation rate represents a loss of value, even though the nominal rate of return might well be greater than 0%. When ROI is adjusted for inflation, the resulting return is considered an increase or decrease in purchasing power. If an ROI value is adjusted for inflation, it is stated explicitly, such as “The return, adjusted for inflation, was 2%.”

Cash or potential cash returns

Time value of money

Investments generate cash flow to the investor to compensate the investor for the time value of money.

Except for rare periods of deflation where the opposite is true, a dollar in cash is worth less today than it was yesterday, and worth more today than it will be worth tomorrow. The main factors that are used by investors to determine the rate of return at which they are willing to invest money include:

- estimates of future inflation rates

- estimates regarding the risk of the investment (e.g. how likely it is that investors will receive regular interest/dividend payments and the return of their full capital)

- whether or not the investors want the money available (“liquid”) for other uses.

The time value of money is reflected in the interest rates that banks offer for deposits, and also in the interest rates that banks charge for loans such as home mortgages. The “risk-free” rate is the rate on U.S. Treasury Bills, because this is the highest rate available without risking capital.

The rate of return which an investor expects from an investment is called the Discount Rate. Each investment has a different discount rate, based on the cash flow expected in future from the investment. The higher the risk, the higher the discount rate (rate of return) the investor will demand from the investment.

Compounding or reinvesting

Compound interest or other reinvestment of cash returns (such as interest and dividends) does not affect the discount rate of an investment, but it does affect the Annual Percentage Yield, because compounding/reinvestment increases the capital invested.

For example, if an investor put $1,000 in a 1-year Certificate of Deposit (CD) that paid an annual interest rate of 4%, compounded quarterly, the CD would earn 1% interest per quarter on the account balance. The account balance includes interest previously credited to the account.

| 1st Quarter | 2nd Quarter | 3rd Quarter | 4th Quarter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital at the beginning of the period | $1,000 | $1,010 | $1,020.10 | $1,030.30 |

| Dollar return for the period | $10 | $10.10 | $10.20 | $10.30 |

| Account Balance at end of the period | $1,010.00 | $1,020.10 | $1,030.30 | $1,040.60 |

| Quarterly ROI | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

The concept of 'income stream' may express this more clearly. At the beginning of the year, the investor took $1,000 out of his pocket (or checking account) to invest in a CD at the bank. The money was still his, but it was no longer available for buying groceries. The investment provided a cash flow of $10.00, $10.10, $10.20 and $10.30. At the end of the year, the investor got $1,040.60 back from the bank. $1,000 was return of capital.

Once interest is earned by an investor it becomes capital. Compound interest involves reinvestment of capital; the interest earned during each quarter is reinvested. At the end of the first quarter the investor had capital of $1,010.00, which then earned $10.10 during the second quarter. The extra dime was interest on his additional $10 investment. The Annual Percentage Yield or Future value for compound interest is higher than for simple interest because the interest is reinvested as capital and earns interest. The yield on the above investment was 4.06%.

Bank accounts offer contractually guaranteed returns, so investors cannot lose their capital. Investors/Depositors lend money to the bank, and the bank is obligated to give investors back their capital plus all earned interest. Since investors are not risking losing their capital on a bad investment, they earn a quite low rate of return. But their capital steadily increases.

Returns when capital is at risk

Capital gains and losses

Many investments carry significant risk that the investor will lose some or all of the invested capital. For example, investments in company stock shares put capital at risk. The value of a stock share depends on what someone is willing to pay for it at a certain point in time. Unlike capital invested in a savings account, the capital value (price) of a stock share constantly changes. If the price is relatively stable, the stock is said to have “low volatility.” If the price often changes a great deal, the stock has “high volatility.” All stock shares have some volatility, and the change in price directly affects ROI for stock investments.

Stock returns are usually calculated for holding periods such as a month, a quarter or a year.

Reinvestment when capital is at risk: rate of return and yield

| End of: | 1st Quarter | 2nd Quarter | 3rd Quarter | 4th Quarter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dividend | $1 | $1.01 | $1.02 | $1.03 |

| Stock Price | $98 | $101 | $102 | $99 |

| Shares Purchased | 0.010204 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.010404 |

| Total Shares Held | 1.010204 | 1.020204 | 1.030204 | 1.040608 |

| Investment Value | $99 | $103.04 | $105.08 | $103.02 |

| Quarterly ROI | -1% | 4.08% | 1.98% | -1.96% |

Yield is the compound rate of return that includes the effect of reinvesting interest or dividends.

To the right is an example of a stock investment of one share purchased at the beginning of the year for $100.

- The quarterly dividend is reinvested at the quarter-end stock price.

- The number of shares purchased each quarter = ($ Dividend)/($ Stock Price).

- The final investment value of $103.02 is a 3.02% Yield on the initial investment of $100. This is the compound yield, and this return can be considered to be the return on the investment of $100.

To calculate the rate of return, the investor includes the reinvested dividends in the total investment. The investor received a total of $4.06 in dividends over the year, all of which were reinvested, so the investment amount increased by $4.06.

- Total Investment = Cost Basis = $100 + $4.06 = $104.06.

- Capital gain/loss = $103.02 - $104.06 = -$1.04 (a capital loss)

- ($4.06 dividends - $1.04 capital loss ) / $104.06 total investment = 2.9% ROI

The disadvantage of this ROI calculation is that it does not take into account the fact that not all the money was invested during the entire year (the dividend reinvestments occurred throughout the year). The advantages are: (1) it uses the cost basis of the investment, (2) it clearly shows which gains are due to dividends and which gains/losses are due to capital gains/losses, and (3) the actual dollar return of $3.02 is compared to the actual dollar investment of $104.06.

For American income tax purposes, if the shares were sold at the end of the year, dividends would be $4.06, cost basis of the investment would be $104.06, sale price would be $103.02, and the capital loss would be $1.04.

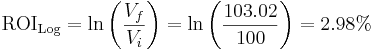

Since all returns were reinvested, the ROI might also be calculated as a continuously compounded return or logarithmic return. The effective continuously compounded rate of return is the natural log of the final investment value divided by the initial investment value:

is the initial investment ($100)

is the initial investment ($100) is the final value ($103.02)

is the final value ($103.02)

.

.

Mutual fund returns

Mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) hold portfolios of various companies' stock shares. When the companies pay a dividend, and when the fund trades shares, dividends and capital gains are distributed to the mutual fund shareholders. Mutual funds trade at the net asset value of the stock shares.

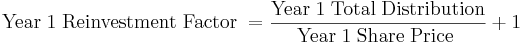

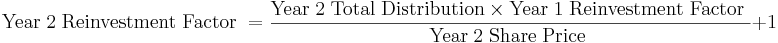

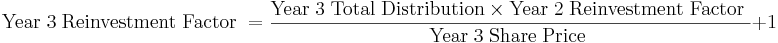

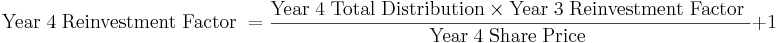

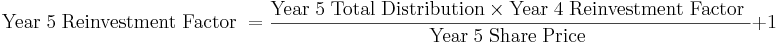

Total returns

Mutual funds report total returns based on reinvestment factors. Reinvestment factors are based on total distributions (dividends plus capital gains) during each period.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Total Return = ((Final Price x Last Reinvestment Factor) - Beginning Price) / Beginning Price

Average annual return (geometric)

Average Annual Return (geometric) US mutual funds use SEC form N-1A to report the average annual compounded rates of return for 1-year, 5-year and 10-year periods as the "average annual total return" for each fund. The following formula is used:[4]

P(1+T)n = ERV

Where:

P = a hypothetical initial payment of $1,000.

T = average annual total return.

n = number of years.

ERV = ending redeemable value of a hypothetical $1,000 payment made at the beginning of the 1-, 5-, or 10-year periods at the end of the 1-, 5-, or 10-year periods (or fractional portion).

= ![\left[ {\left(1 + \frac{{\rm Cumulative\; Return}}{100}\right)}^{{\rm Time\; in\; years}^{-1}} - 1 \right] \times 100](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/8595aafd431caacb296ce47701e8f9c1.png)

Example

| End of: | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dividend | $5 | $5 | $5 | $5 | $5 |

| Capital Gain Distribution | $2 | ||||

| Total Distribution | $5 | $5 | $7 | $5 | $5 |

| Share Price | $98 | $101 | $102 | $99 | $101 |

| Shares Purchased | 0.05102 | 0.04950 | 0.06863 | 0.05051 | 0.04950 |

| Shares Owned | 1.05102 | 1.10053 | 1.16915 | 1.21966 | 1.26916 |

| Reinvestment Factor | 1.05102 | 1.05203 | 1.07220 | 1.05415 | 1.05219 |

- Total Return = (($101 x 1.05219) - $100) / $100 = 6.27% (net of expenses)

- Average Annual Return (geometric) = (((28.19)/100)+1) ^ (1/5)) – 1) x 100 = 5.09%

Using a Holding Period Return calculation, after 5 years, an investor who reinvested owned 1.26916 share valued at $101 per share ($128.19 in value). ($128.19-$100)/$100/5 = 5.638% yield. An investor who did not reinvest received a total of $27 in dividends and $1 in capital gain. ($27+$1)/$100/5 = 5.600% return.

Mutual funds include capital gains as well as dividends in their return calculations. Since the market price of a mutual fund share is based on net asset value, a capital gain distribution is offset by an equal decrease in mutual fund share value/price. From the shareholder's perspective, a capital gain distribution is not a net gain in assets, but it is a realized capital gain.

Summary: overall rate of return

Rate of Return and Return on Investment indicate cash flow from an investment to the investor over a specified period of time, usually a year.

ROI is a measure of investment profitability, not a measure of investment size. While compound interest and dividend reinvestment can increase the size of the investment (thus potentially yielding a higher dollar return to the investor), Return on Investment is a percentage return based on capital invested.

In general, the higher the investment risk, the greater the potential investment return, and the greater the potential investment loss.

References

- ↑ Damato,Karen. Doing the Math: Tech Investors' Road to Recovery is Long. Wall Street Journal, pp.C1-C19, May 18, 2001

- ↑ Barron's Finance, 4th Edition. New York. 2000. pp. pp 442-456. ISBN 0-7641-1275-9.

- ↑ Barron's Finance. pp. pp 151-163.

- ↑ SEC (1998). "[http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-7512f.htm#E12E2 Final Rule: Registration Form Used by Open-End Management Investment Companies: Sample Form and instructions]".

See also

- Average for a discussion of annualization of returns.

- Compound interest

- Capital budgeting

- Compound annual growth rate

- Expected return

- Internal rate of return

- Net Present Value

- Rate of profit

- Return on assets

- Return on capital

- Return of capital

- Value investing

External links

Further reading

- A. A. Groppelli and Ehsan Nikbakht. Barron’s Finance, 4th Edition. New York: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., 2000. ISBN 0-7641-1275-9

- Zvi Bodie, Alex Kane and Alan J. Marcus. Essentials of Investments, 5th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2004. ISBN 0-07-251077-3

- Richard A. Brealey, Stewart C. Myers and Franklin Allen. Principals of Corporate Finance, 8th Edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2006

- Walter B. Meigs and Robert F. Meigs. Financial Accounting, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1970. ISBN 0-07-041534-X

- Bruce J. Feibel. Investment Performance Measurement. New York: Wiley, 2003. ISBN 0471268496