Rail gauge

Rail gauge is the distance between the inner sides of the two parallel rails that make up a single railway line. Sixty percent of the world's railways use a gauge of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in), which is known as standard or international gauge. Gauges wider than this are called broad gauge, smaller narrow gauge. The term break-of-gauge refers to a place where different gauges meet. Some stretches of track are dual gauge, with three (or sometimes four) rails in place of the usual two, to allow trains of two or more different gauges to share the same path. Gauge conversion can be used to reduce break-of-gauge situations.

| Rail gauge |

|---|

| Broad gauge |

| Standard gauge |

| Narrow gauge |

| Minimum gauge |

| List of rail gauges |

| Break-of-gauge |

| Dual gauge |

| Gauge conversion |

| Rail tracks |

| Tramway track |

| [edit] |

Contents |

Overview

New railways are usually built to standard gauge unless there is a compelling reason to adopt another gauge, e.g., compatibility with existing railways. The advantages of using standard gauge are:

- It facilitates inter-running with neighbouring railways

- Locomotives and rolling stock can be ordered from manufacturers' standard designs and do not need to be custom built. However, some adaptation to local conditions may still be necessary, e.g. in respect of loading gauge.

Dominant gauges

| Gauge | Name | Installation | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in) | Indian gauge | India (Project Unigauge - 42,000 km), Pakistan, Argentina, Chile | |

| 1,668 mm (5 ft 5⅔ in) | Iberian gauge | 14,337.2 km (2007)

+ 21 km mixed gauge in Spain (Iberian+UIC, three rails on the same sleeper) |

Portugal, Spain |

| 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) | Irish gauge | 9,800 km | Ireland and important minor gauge in Australia - Victorian gauge (4,017 km), Brazil (4,057 km) |

| 1,524 mm (5 ft) | Russian gauge | 7,000 km | Finland, Estonia |

| 1,520 mm (4 ft 11⅞ in) | Russian gauge | 220,000 km | CIS states, Latvia, Lithuania, Mongolia |

| 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in) | Standard gauge | 720,000 km | Europe, North America, China, Australia, Middle East (60% of the world's railways) |

| 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Cape gauge | 112,000 km | Southern and Central Africa, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, New Zealand, Australia (parts) |

| 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) | Metre gauge | 95,000 km | SE Asia, India (17,000 km, some under gauge conversion with Project Unigauge to Indian gauge, Brazil (23,489 km) |

Installation data from forum1520, except for Irish.

For details see: List of rail gauges

Note: Russian gauge can be 1524 mm or 1520 mm.

History

Historically, the choice of gauge was partly arbitrary and partly a response to local conditions. Narrow-gauge railways are cheaper to build and can negotiate sharper curves but broad-gauge railways give greater stability and permit higher speeds. Standard gauge is a compromise between the narrow and broad gauges.

Early origins of the standard gauge

There is a story that rail gauge was derived from the rutways created by war chariots used by Imperial Rome, which everyone else had to follow to preserve their wagon wheels, and because Julius Caesar set this width under Roman law so that vehicles could traverse Roman villages and towns without getting caught in stone ruts of differing widths (another example is Qin Shihuang's law of a standard gauge for carriages and chariots after his unification of China). A problem with this story is that the Roman military did not use chariots in battle. However an equal gauge is probably coincidence. Excavations at the buried cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum revealed ruts averaging 1,448 mm (4 ft 9 in) centre to centre, with a gauge of 1,372 mm (4 ft 6 in).

The designers of both chariots and trams and trains were dealing with a similar issue, hauling wheeled vehicles behind draft animals. A more likely theory as to why the 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in) measurement was chosen is that it reflects vehicles with a 1,524 mm (5 ft) "outside" gauge.

Italy defined its gauges from the centres of each rail [1], rather than the inside edges of the rails, giving some unusual measurements (for example, 950 mm instead of 1000 mm). According to the law of 28 July 1879, the only legal gauges in Italy were 1500, 1000 and 750 mm measured on the middle of the rail, corresponding to 1445, 950, and 700 mm inside the rail.

Standard gauge

The standard gauge of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in) was chosen for the first main-line railway, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR), by the British engineer George Stephenson; the de facto standard for the colliery railways where Stephenson had worked was 4 ft 8 in. Whatever the origin of the gauge, it seemed to be a satisfactory choice: not too narrow and not too wide.

Brunel on the Great Western Railway chose the broader gauge of 2,140 mm (7 ft 0¼ in) not only because it offered greater stability and capacity at high speed but also because the Stephenson gauge was not scientifically selected. The Eastern Counties Railway chose five-foot gauge, but soon realised that lack of compatibility was a mistake and changed to Stephenson's gauge. The conflict between Brunel and Stephenson is often referred to as the Gauge War. Several non-interconnecting lines in Scotland were 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in) but were changed to standard gauge for compatibility reasons.

In 1845 a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland Royal Commission recommended adoption of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in) as standard gauge in Great Britain; and in Ireland a standard gauge of 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm). The following year the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Gauge Act, which required that new railways use the standard gauge. Except for the Great Western Railway's broad gauge, few main-line railways in Great Britain used a different gauge. The last Great Western line was converted to standard gauge in 1892.

Broad gauge

Broad gauge is a blanket term that refers to any gauge wider than standard gauge or 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in). Russian, Indian, Irish, and Iberian gauges are all broad gauges. Broad gauge railroads are also common for cranes in docks for short distances. Broad gauge is used to provide better stability or to prevent the easy transfer of rolling stock from railroads of other countries for political or military reasons. Compare with narrow gauge.

Russian gauge

Russian gauge is 1,520 mm (4 ft 11⅞ in) and is the second most widely used gauge in the world.

Engineer Pavel Melnikov hired George Washington Whistler, a prominent American railroad engineer (and father of the artist James McNeill Whistler), to be a consultant on the building of Russia's first major railroad, the Moscow–Saint Petersburg line. The selection of 1,500 mm (4 ft 111⁄16 in) gauge was recommended by German and Austrian engineers but not adopted: it was not the same as the 1,524 mm (5 ft) gauge in common use in the southern United States at the time. Russian gauge was defined as 1,524 mm (5 ft) on September 12 1842 and standardised to the present 1,520 mm (4 ft 11⅞ in) in the late 1960s.

The interconnected and compatible system covers Russia and most of the former Soviet Union, including the Baltic states, Ukraine, Belarus, the Caucasian and Central Asian republics and Mongolia.

Curiosities

Finland, which was a Grand Duchy under Russia in the 19th century, uses 1,524 mm (5 ft) gauge. Upon gaining independence in 1917 much thought was given to converting to standard gauge, but nothing came of it. Most of Finland's rail-freight trade is still with Russia, and this trade continues because the Russian 1,520 mm (4 ft 11⅞ in) gauge is close enough to allow through-running.

The unconnected system on Sakhalin Island, in the far east of Russia, has retained the previous Japanese 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge, as originally built. In 2004 a project was presented to convert this system to Russian gauge.

Iberian gauge

The main railway networks of Spain and Portugal were constructed to gauges of six Castilian feet, 1,672 mm (5 ft 55⁄6 in) and five Portuguese feet, 1,664 mm (5 ft 5½ in). The two gauges were sufficiently close to allow inter-operation of trains, and in recent years they have both been adjusted to a common "Iberian gauge" (ancho ibérico or trocha ibérica in Spanish, bitola ibérica in Portuguese) of 1,668 mm (5 ft 5⅔ in). Although it has been said that the main reason for the adoption of this non-standard gauge was to obstruct any French invasion attempts, it was a technical decision to allow for the running of larger more powerful locomotives in a mountainous country [1].

Since the beginning of the 1990s new high-speed passenger lines in Spain have been built to standard gauge of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in), to allow these lines to link to the European high-speed network. Although the 22 km from Tardienta to Huesca (part of a branch from the Madrid to Barcelona high-speed line) has been reconstructed as mixed Iberic and standard gauge, in general the interface between the two gauges in Spain is dealt with by gauge-changing installations, which can adjust the gauge of appropriately designed wheelsets on the move [2] [3].

There are plans to convert the whole broad gauge network to standard gauge, but so far the only visible indication is the use of dual-gauge concrete sleepers with two positions of bolt holes on stretches of relaid broad-gauge track.

Indian gauge

Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka inherited a diversity of rail gauges, of which 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in) was predominant. Indian Railways has adopted Project Unigauge, which seeks to systematically convert most of its narrower gauge railways to 1,676 mm.

Irish gauge

The gauge adopted by the main-line railways in Ireland is 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm). This unusual gauge is otherwise found only in the Australian states of Victoria, southern New South Wales (as part of the Victorian rail network) and South Australia (where it was introduced by the Irish railway engineer F. W. Sheilds), and Brazil.

The first three railways all had different gauges: the Dublin and Kingstown Railway, 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm); the Ulster Railway, 6 ft 2 in (1,880 mm); and the Dublin and Drogheda Railway, 5 ft 2 in (1,575 mm). The Board of Trade, recognising the chaos that would ensue, investigated the matter, and in 1843 recommended the use of 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm).

This was given legal status by the Railway Regulation (Gauge) Act of 1846[4] which specified 4 feet 8 ½ inches for Great Britain, and 5 feet 3 inches for Ireland.

Australian gauge

In the 19th century Australia's three mainland states adopted standard gauge, but due to political differences a break of gauge 30 years in the future was created. After instigating a change to 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) agreed to by all, New South Wales reverted to standard gauge while Victoria and South Australia stayed with broad gauge. Three different gauges are currently in wide use in Australia, and there is little prospect of full standardisation, though the main interstate routes are now standard gauge.

Narrow gauge

In many areas narrow gauge was chosen. Narrow gauge railways generally cannot handle as much tonnage as standard gauge (although there are significant exceptions), but they are generally less costly to construct, particularly in mountainous regions because the turning radius of curves can be less. Many narrow gauge railways were built in the Rocky Mountains of the United States and Canada for these reasons, although most have since been abandoned or converted to standard gauge. Industrial railways are often narrow gauge, and sugar cane and banana plantations are often served by narrow gauges such as 2 ft (610 mm), as there is little through traffic to other systems.

The most widely used narrow gauges are

- 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) Cape gauge (e.g. Southern and Central Africa, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, parts of Australia, New Zealand)

- 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) metre gauge (e.g. SE Asia, 17,000 km in India, but gauge conversion with Project Unigauge)

There are also minimum gauge railways.

Break of gauge

When a railway line of one gauge meets a line of another gauge there is a break of gauge. A break of gauge adds cost and inconvenience to traffic that passes from one system to another.

An example of this is on the Transmanchurian Railway, where Russia and Mongolia use broad gauge while China uses standard gauge. At the border, each carriage has to be lifted in turn to have its bogies changed. The whole operation, combined with passport and customs control, can take several hours.

Other examples include crossings into or out of the former Soviet Union: Ukraine/Slovakia border on the Bratislava-L'viv train, and from the Romania/Moldova border on the Chisinau-Bucharest train.[5]

This can be avoided however by implementing a system similar to that once used in Australia, where lines between states using different gauges were converted to dual gauge with three rails, one set of two forming a standard gauge line, with the third rail either inside or outside the standard set forming rails at either narrow or broad gauge. As a result, trains built to either gauge can use the line.

Dual gauge

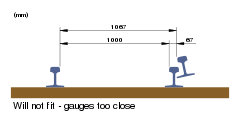

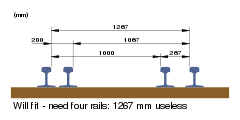

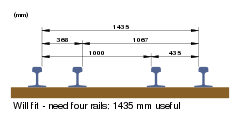

Dual gauge allows trains of different gauges to share the same track. This can save considerable expense compared to using separate tracks for each gauge, but introduces complexities in track maintenance and signalling, as well as requiring speed restrictions for some trains. If the difference between the two gauges is large enough, for example between 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), three-rail dual-gauge is possible, but if the difference is not large enough, for example between 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) and 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in), four-rail dual-gauge is used. Dual-gauge rail lines are used in the railway networks of Switzerland, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, North Korea, Tunisia and Vietnam.

Africa

|

|

|

| 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauges are too close to allow three-rail dual gauge. | 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauges can be used together, with four-rail dual gauge - note the third (useless) 1267 mm gauge. | 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauges can be used together with four-rail dual gauge, with bonus 1435 mm standard gauge. |

Africa is particularly affected by gauge problems, where railways of different gauges in adjacent countries meet.

Gauge rationalisation in Africa is facilitated since four-rail dual gauge of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) contains a hidden gauge, which can be made to be standard gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in). The four-rail system reuses and doubles the effective strength of the old light rails, which might otherwise have only a low value reuse as fenceposts.

Variable gauge axles

Variable gauge axles (VGA), developed by the Talgo company and Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) of Spain, amongst others, enable trains to change gauge with only a few minutes spent in the gauge conversion process. The same system is also used between China and Central Asia, and Poland and Ukraine (SUW 2000 and INTERGAUGE variable axles system).[6] China and Poland are standard gauge, while Central Asia and Russia are 1520 mm gauge.

Designed for Conversion

Equipment can be designed for easy conversion, such as the Garratt locomotives on the Kenya and Uganda Railway designed for conversion from 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) to 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in). [7] Several classes of locomotives of the Victorian Railways were designed for easy conversion from 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) to 1,435 mm (4 ft 8½ in). Only one preserved historic locomotives is to actually be converted .

Future

Further standardization of rail gauges seems likely, as individual countries seek to build inter-operable national networks, and international organizations seek to build macro-regional and continental networks. National projects include the Australian and Indian efforts mentioned above to create a uniform gauge in their national networks. The European Union has set out to develop inter-operable freight and passenger rail networks across the EU area, and is seeking to standardize track gauge, signalling and electrical power systems. EU funds have been dedicated to convert key railway lines in the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia from 1520 mm gauge to standard gauge, and to assist Spain and Portugal in the construction of high-speed rail lines to connect Iberian cities to one another and to the French high-speed lines. The EU has developed plans for improved freight rail links between Spain, Portugal, and the rest of Europe.

High speed

Except in Russia and neighbouring states, all high-speed rail systems use standard gauge, even in countries like Japan, Taiwan, Spain and Portugal where most of the existing rail lines use a different gauge. Once standard gauge high-speed networks exist, they may provide the impetus for gauge conversion of existing passenger lines to allow for interoperability. All high speed lines have adopted 25 kV, 50 Hz AC, overhead line as the standard electrification system except in Germany, Sweden, Norway and Switzerland (15 kV AC), the first high speed lines in Italy (3000 V DC), the Tōkaidō, Sanyō and Kyūshū Shinkansen lines in Japan (25 kV 60 Hz) and the United States, which uses 25 kV 60 Hz in new construction, but has older 12 kV segments.

Mining

Mining railways, which have little interconnection with other lines, also tend to choose standard gauge to allow them to use off-the-shelf equipment, especially heavy-duty rolling stock.

The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) is planning a Trans-Asian Railway that will link Europe and the Pacific, with a Northern Corridor from Europe to the Korean Peninsula, a Southern Corridor from Europe to Southeast Asia, and a North-South corridor from Northern Europe to the Persian Gulf. All the proposed corridors would encounter one or more breaks of gauge as they cross Asia. Current plans have mechanized facilities at the breaks of gauge to move shipping containers from train to train rather than widespread gauge conversion.

- Rail lines for iron ore to Oakajee port in Western Australia are proposed to form a combined dual gauge network.

- Rail lines for iron ore to Kribi in Cameroon are likely to be 1435 mm with a likely connection to the same port from the 1000 mm gauge Cameroon system.

Kenya-Uganda-Sudan proposal

A proposal was aired in October 2004 [8] [9] [10] [11] to build a high-speed electrified line to connect Kenya with southern Sudan. Kenya and Uganda use 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) gauge, while Sudan uses 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge. By choosing standard gauge for the project, the gauge incompatibility is overcome. A bonus is that Egypt, further north, uses standard gauge. Since the existing narrow gauge track is quite likely of a "pioneer" standard, with sharp curves and low-capacity light rails, substantial reconstruction of the existing lines are needed, so gauge unification would be reasonable.

Congo-Rwanda-Tanzania

Developments in 2007 may see several lines of 1000 mm and 1067 mm gauges meet in Rwanda

Latin America

- 2008 - FERISTSA line from Mexico to Panama - standard gauge (Mexico is already linked to the United States and Canada)

- 2008 - FERISTSA to VCE - missing link - Panama - Colombia

- 2008

proposed VCE link between Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador [12]

proposed VCE link between Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador [12] - 2008 - VBA - Venezuela via Brazil to Argentina - standard gauge

See also

|

|

|

References

- ↑ Ancho de via

- ↑ Talgo Date=2008-09-04

- ↑ CAF

- ↑ Railway Regulation (Gauge) Act 1846 (PDF)

- ↑ "Beyond Thunderdome: Iron Curtain 2k6". Retrieved on 2007-10-10.

- ↑ Experience and results of operation the SUW 2000 system in traffic corridors

- ↑ http://www.garrattmaker.com/history.html

- ↑ Nepad < Nepad News >

- ↑ SudanTribune article : After 21 years of civil war, railway to link Sudan and Kenya

- ↑ People's Daily Online - Roundup: Kenya, southern Sudan to enhance ties

- ↑ http://sd2.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/chinanews/200501/20050100014390.html

- ↑ RailPage

External links

- A history of track gauge by George W. Hilton

- Railroad Gauge Width — A list of railway gauges used or being used worldwide, including gauges that are obsolete.

- European Railway Agency: 1520 mm systems (issues with the participation of 1520/1524 mm gauge countries in the EU rail network)

- The Indian Railways FAQ: Gauges

- The Days they Changed the Gauge in the U.S. South

- The myth that standard gauge derives from the specification for an Imperial Roman war chariot. (Urban Legends Reference Pages)

|

||||||||||||||