RMS Lusitania

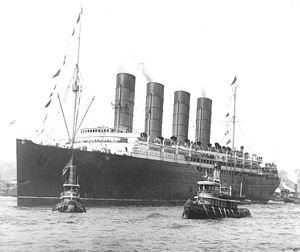

The Lusitania arriving in New York during her maiden voyage. 13 September 1907 |

|

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | RMS Lusitania |

| Owner: | Cunard Line |

| Port of Registry: | Liverpool, |

| Builder: | John Brown & Co. Ltd, Clydebank, Scotland |

| Laid down: | 16 June 1904 |

| Launched: | Thursday, 7 June 1906[1] |

| Christened: | by Mary, Lady Inverclyde[2] |

| Maiden voyage: | 7 September 1907 |

| Fate: | Torpedoed by German U-boat U-20 on Friday 7 May 1915. 1959 on-board (1,198 dead and 761 survivors). Wreck lies approximately 7 miles (11 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale Lighthouse in 450 feet (140 m) of water. |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 31,550 gross register tons (GRT) |

| Displacement: | 44,060 Long Tons |

| Length: | 787 ft (239.88 m)[3] |

| Beam: | 87 ft (26.52 m) |

| Installed power: | 25 Scotch boilers. Four direct-acting Parsons steam turbines producing 76000hp. |

| Propulsion: | Four triple blade propellers. (Quadruple blade propellers installed in 1909). |

| Speed: | 25 knots (46.3 km/h / 28.8 mph) Top speed (single day's run): 26.7 knots (49.4 km/h) (March, 1914) |

| Capacity: | 552 first class, 460 second class, 1,186 third class. 2,198 total |

| Crew: | 850 |

RMS Lusitania was a British luxury ocean liner owned by the Cunard Steamship Company and built by John Brown and Company of Clydebank, Scotland. Christened and launched on Thursday, 7 June 1906, Lusitania met a disastrous end as a casualty of the First World War when she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-20 on 7 May 1915. The great ship sank in just 18 minutes, eight miles (15 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, killing 1,198 of the people aboard. The sinking turned public opinion in many countries against Germany, and was probably a major factor in the eventual decision of the United States to join the war in 1917. Some people believe that the ship was a blockade runner, and thus a legitimate target. It is often considered by historians to be the second most famous civilian passenger liner disaster after the sinking of Titanic.

Contents |

Construction and trials

Owned by the Cunard Steamship Company and built by John Brown and Company, Lusitania was named for the ancient Roman province of Lusitania, in present day Portugal. Lusitania sailed on her maiden voyage to New York City on 7 September 1907, arriving on 13 September 1907, thus taking back the Blue Riband record for westbound crossing from the Deutschland.

Lusitania and her sister, Mauretania, were built during the time of a passenger liner race between shipping lines based in Germany and Great Britain, and were the fastest liners of their day. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the fastest Atlantic liners were German, and the British sought to win back the title. Simultaneously, American financier J.P. Morgan was planning to buy up all the North Atlantic shipping lines, including Britain's own White Star Line. In 1903, Cunard chairman Lord Inverclyde took these threats to his advantage and lobbied the Balfour administration for a loan of £2.6 million to construct Lusitania and Mauretania, providing they met Admiralty specifications and Cunard remained a wholly British company. The British Government also agreed to pay Cunard an annual subsidy of £150,000 for maintaining both ships in a state of war readiness, plus an additional £68,000 to carry Royal Mail.

Lusitania's keel was laid at John Brown & Clydebank as Yard no. 367 on 16 June 1904. She was launched and christened by Mary, Lady Inverclyde, on Thursday, 7 June 1906.[4][5] Lord Inverclyde(1861-1905) had died before this momentous occasion.

Much of the trim on Lusitania was designed and constructed by the Bromsgrove Guild.[6]

Starting on 27 July 1907, Lusitania underwent preliminary and formal acceptance trials. It was then she smashed all speed records ever set in the history of the shipping industry. The builder's engineers and Cunard officials discovered high speed caused violent vibrations in the stern, forcing the fitting of stronger bracing. After these physical alterations, she was finally delivered to Cunard on 26 August.

Comparison with the Olympic class

Lusitania and Mauretania were smaller than White Star Line's Olympic class vessels, Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic, but entered service five years earlier. Although significantly faster than the Olympics, they were not fast enough to allow Cunard to provide a weekly transatlantic departure schedule with just two vessels. Consequently, Cunard would require a third ship to maintain a weekly service, and after White Star announced plans to build the Olympics, Cunard ordered a third ship, Aquitania. Like the White Star trio, Aquitania would be slower but larger and more luxurious than her sisters.

The Olympics also differed from Lusitania and Mauretania in the subdivision of underwater compartments. The Olympics were divided by transverse watertight bulkheads. Lusitania also had transverse bulkheads, but in addition had longitudinal bulkheads on each side, between the boiler and engine rooms and the coal bunkers on the outside of the vessel. The British commission that investigated the Titanic disaster heard testimony flooding of bunkers outside of longitudinal bulkheads over a considerable length could increase the ship's list and "make the lowering of the boats on the other side impracticable" — exactly what later happened with Lusitania.[7]

Career

Lusitania departed Liverpool for her maiden voyage on 7 September 1907 under the command of Commodore James Watt of the Cunard Line and arrived in New York City on 13 September. At the time she was the largest ocean liner in service and would continue to be until the introduction of her sister Mauretania in November that year. During her eight-year service, she made a total of 202 crossings on the Cunard Line's Liverpool-New York Route.

In October 1907 Lusitania took the Blue Riband for eastbound crossing from Kaiser Wilhelm II of the North German Lloyd, ending Germany's 10-year dominance of the Atlantic. Lusitania averaged 23.99 knots (44.4 km/h) westbound and 23.61 knots (43.7 km/h) eastbound.

With the introduction of Mauretania in November 1907, Lusitania and Mauretania continued to swap the Blue Riband. Lusitania made her fastest westbound crossing in 1909, averaging 25.85 knots (47.9 km/h). In September of that same year, she lost it permanently to Mauretania.

Hudson Fulton celebration

Lusitania and other ships participated in the Hudson Fulton celebration in New York City from the end of September to early October 1909. This was in celebration of the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson's trip up the river that bears his name and the 100th anniversary of Robert Fulton's steamboat, Clermont. The celebration also was a display of the different modes of transportation then in existence, Lusitania representing the newest advancement in steamship technology. A newer mode of travel was the aeroplane. Wilbur Wright had brought a Flyer to Governors Island and proceeded to make demonstration flights before millions of New Yorkers who had never seen an airplane. Some of Wright's trips were directly over Lusitania; a few interesting photographs of Lusitania from that week still exist.

War

Lusitania, like a number of liners of the era, was part of a subsidy scheme meant to convert ships into armed merchant cruisers if requisitioned by the government. This involved structural provisions for mounting deck guns. In 1913, during her annual overhaul, Lusitania was fitted with gun mounts on her port and starboard bow sides, hidden from passengers under large coils of docking rope.

At the onset of World War I, the British Admiralty considered Lusitania for requisition as an armed merchant cruiser; however, large liners such as Lusitania consumed too much coal, presented too large a target, and put at risk large crews and were therefore deemed inappropriate for the role. They were also very distinctive; smaller liners were used as transports, instead.

The large liners were either not requisitioned, or were used for troop transport or as hospital ships. Mauretania became a troop transport while Lusitania continued in her Cunard service as a luxury liner built to convey people between Great Britain and the United States. To reduce costs Lusitania's transatlantic crossings were reduced to one monthly, and boiler room Number 4 was shut down. Maximum speed was reduced to 21 knots (39 km/h), but even then, Lusitania was the fastest passenger liner on the North Atlantic in commercial service and 10 knots (18.5 km/h) faster than submarines.

On 4 February 1915 Germany declared the seas around the British Isles a war zone: from 18 February Allied ships in the area would be sunk without warning. This was not wholly unrestricted submarine warfare since efforts would be taken to avoid sinking neutral ships.[8]

Lusitania was scheduled to arrive in Liverpool on 6 March 1915. The Admiralty issued her specific instructions on how to avoid submarines. Despite a severe shortage of destroyers, Admiral Henry Oliver ordered HMS Louis and Laverock to escort Lusitania, and took the further precaution of sending the Q ship Lyons to patrol Liverpool Bay . Captain Dow of Lusitania, not knowing whether Laverock and Louis were actual Admiralty escorts or a trap by the German navy, evaded the escorts and arrived in Liverpool without incident.[9]

On 17 April 1915 Lusitania left Liverpool on her 201st transatlantic voyage, arriving in New York on 24 April. A group of German–Americans, hoping to avoid controversy if Lusitania were attacked by a U-boat, discussed their concerns with a representative of the German embassy. The embassy decided to warn passengers before her next crossing not to sail aboard Lusitania.

The Imperial German embassy placed a warning advertisement in American newspapers, including those in New York.

Last voyage and sinking

Last departure

Lusitania departed Pier 54 in New York on 1 May 1915. The German Embassy in Washington had issued this warning on 22 April.[10]

-

NOTICE! - TRAVELLERS intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travellers sailing in the war zone on the ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

-

IMPERIAL GERMAN EMBASSY,

Washington, D.C. 22 April 1915

This warning was printed right next to an advertisement for Lusitania's return voyage. The warning led to some agitation in the press and worried the ship's passengers and crew.

Captain William Thomas Turner, known as "Bowler Bill", had returned to his old command, Lusitania. He was commodore of the Cunard Line and a highly experienced master mariner, and had recently relieved Daniel Dow, the ship's regular captain. Dow had been instructed by his chairman, Alfred Booth, to take some leave, following his protestations that the ship should not become an armed merchant cruiser, making it a prime target for German forces.[11]. Captain Turner tried to calm the passengers by explaining that the ship's speed made it safe from attack by submarine.

Lusitania steamed out of New York at noon that day, two hours behind schedule due to a transfer of passengers and crew from the recently requisitioned Cameronia. Shortly after departure, three blind passengers (evidently stowaways) were found on board and detained below decks.

Passengers

Lusitania carried 1,959 passengers on her last voyage. Those aboard included a large number of illustrious and renowned people such as:

- Canadian businessman Sir Frederick Orr Lewis, 1st Baronet (survived)

- William R. G. Holt, son and heir of Canadian banker Sir Herbert Samuel Holt (survived)

- Montreal socialite Frances McIntosh Stephens, wife of politician George Washington Stephens (died)

- Mary Crowther Ryerson of Toronto, wife of George Sterling Ryerson, founder of the Canadian Red Cross (died)

- Lindon W. Bates, Jr., New York engineer, economist and political figure (died)

- British MP David Alfred Thomas (survived)

- His daughter Margaret, Lady Mackworth, British suffragist (survived)

- Theodate Pope Riddle, American architect and philanthropist (survived)

- Edwin W. Friend, professor of philosophy at Harvard University and co-founder of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) (died) (left a wife five months pregnant behind)

- Oxford professor and writer Ian Holbourn (survived)

- H. Montagu Allan's wife Marguerite (survived) and daughters Anna (died) and Gwendolyn (died)

- Actresses Rita Jolivet (survived), Josephine Brandell (survived) and Amelia Herbert (died)

- Belgian diplomat Marie Depage (died), wife of surgeon Antoine Depage

- New York fashion designer Carrie Kennedy (died) and her sister, Kathryn Hickson (died)

- American building contractor and hotel proprietor Albert Bilicke (died)

- Renowned chemist Anne Justice Shymer, president of the United States Chemical Company (died)

- Playwright Charles Klein (died)

- American writer Justus Miles Forman (died)

- American theatre impresario Charles Frohman (died)

- American philosopher, writer and Roycroft founder Elbert Hubbard (died)

- His wife Alice Moore Hubbard, author and woman's rights activist (died)

- Wine merchant and philanthropist George Kessler (survived)

- American pianist Charles Knight (died) and sister, Elaine Knight (died)

- Renowned Irish art collector and founder of the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery in Dublin Sir Hugh Lane (died)

- American socialite Beatrice Witherbee (survived), wife of Alfred S. Witherbee, president of the Mexican Petroleum Solid Fuel Company

- Her son Alfred Scott Witherbee, Jr. (died) and her mother, Mary Cummings Brown (died)

- American engineer and entrepreneur Frederick Stark Pearson (died) and his wife Mabel (died)

- Genealogist Lothrop Withington (died)

- Sportsman, millionaire, leader of the Vanderbilt family, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt (died) -- last seen fastening a life vest onto a woman holding a baby.

- Scenic designer Oliver P. Bernard (survived), whose sketches of the sinking were published in the Illustrated London News

- Politician and future United States' ambassador to Spain, Ogden Haggerty Hammond of Louisville, Kentucky (survived) and his first wife, Mary Picton Stevens of Hoboken, New Jersey (died), a descendant of John Stevens and Robert Livingston Stevens (parents of former New Jersey Congresswoman Millicent Fenwick)

- Dr. Howard L. Fisher, brother of Walter L. Fisher, former United States Secretary of the Interior (survived)

- Herbert S. Stone, New York newspaper editor and publisher, creator of magazines The Chap Book and The House Beautiful, son of Melville Elijah Stone (died)

- Rev. Dr. Basil W. Maturin, British theologist, author and rector of St. Clement's Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (died)

- Debutant Miss Phyllis Hutchinson, 20-year-old niece of businessman Robert A. Franks of West Orange, New Jersey, financial agent for Andrew Carnegie (died)

- Irish composer and conductor Thomas Whitwell Butler, better known by his pen name T. O'Brien Butler (died)

- Arthur H. Adams, president of the United States Rubber Company (died)

- James A. Dunsmuir, of Toronto, Canadian soldier, younger son of James Dunsmuir (died)

- Charles T. Jeffery, automobile manufacturer who became head of the Thomas B. Jeffery Company after his father's death (survived)

- Paul Crompton, director of Booth Steamship Company Ltd. (died)

- His wife Gladys (died), six children (died), and nanny (died)

- Elisabeth Antill Lassetter, wife of Major General Harry B. Lassetter and sister of Major General John M. Antill (survived)

- Josephine Eaton Burnside, daughter of Canadian department store founder Timothy Eaton (survived), and her daughter Iris Burnside (died)

Eastbound

Lusitania's landfall on the return leg of her transatlantic circuit was Fastnet Rock, off the southern tip of Ireland. As the liner steamed across the ocean, the British Admiralty, by means of wireless intercepts, was tracking the movements of U-20, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger and operating along the west coast of Ireland and moving south.

On 5 and 6 May U-20 sank three vessels in the area of Fastnet Rock, and the Royal Navy sent a warning to all British ships: "Submarines active off the south coast of Ireland". Captain Turner of Lusitania was given the message twice on the evening of the 6th, and took what he felt were prudent precautions. He closed watertight doors, posted double lookouts, ordered a black-out, and had the lifeboats swung out on their davits so that they could be launched quickly if necessary. That evening a Seamen's Charities fund concert took place in the first class lounge.

At about 11:00, on Friday, 7 May, the Admiralty radioed another warning, and Turner adjusted his heading northeast, apparently thinking submarines would be more likely to keep to the open sea, so that Lusitania would be safer close to land.[12]

U-20 was low on fuel and only had three torpedoes left, and Schwieger had decided to head for home. She was moving at top speed on the surface at 13:00 when Schwieger spotted a vessel on the horizon. He ordered U-20 to dive and to take battle stations. The previous week, U-20 had encountered a small cargo vessel and allowed the crew to escape in the boats before sinking it; Schweiger could have allowed the crew and passengers of the Lusitania to take to the boats, but due to the Q-ship program, he considered the danger of being rammed or fired upon by deck guns too great. The Lusitania's captain had, in fact, been ordered to ram any U-boat that surfaced; a cash bonus had been offered for successful ramming.

Sinking

Lusitania was approximately 30 miles (48 km) from Cape Clear Island when she encountered fog and reduced speed to 18 knots.[13] She was making for the port of Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, 70 kilometres (43.5 miles) from the Old Head of Kinsale when the liner crossed in front of U-20 at 14:10.

One story states that when Kapitänleutnant Schwieger of the U-20 gave the order to fire, his quartermaster, Charles Voegele, would not take part in an attack on women and children, and refused to pass on the order to the torpedo room — a decision for which he was court-martialed and served three years in prison at Kiel.[14] However, the story may be apocryphal; Diana Preston writes in Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy that Voegele was an electrician on board U-20 and not a quartermaster.

The torpedo struck Lusitania under the bridge, sending a plume of debris, steel plating and water upward and knocking Lifeboat #5 off its davits, and was followed by a much larger secondary explosion in the starboard bow. Schwieger's log entries attest that he only fired one torpedo, but some doubt the validity of this claim, contending that the German government subsequently doctored Schwieger's log,[15] but accounts from other U-20 crew members corroborate it.

Lusitania's wireless operator sent out an immediate SOS and Captain Turner gave the order to abandon ship. Water had flooded the ship's starboard longitudinal compartments, causing a 15-degree list to starboard. Captain Turner tried turning the ship toward the Irish coast in the hope of beaching her, but the helm would not respond as the torpedo had knocked out the steam lines to the steering motor. Meanwhile, the ship's propellers continued to drive the ship at 18 knots (33 km/h), forcing more water into her hull.

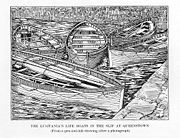

Lusitania's severe starboard list complicated the launch of her lifeboats — those to starboard swung out too far to step aboard safely.[16] While it was still possible to board the lifeboats on the port side, lowering them presented a different problem. As was typical for the period, the hull plates of the Lusitania were riveted, and as the lifeboats were lowered they dragged on the rivets, which threatened to seriously damage the boats before they landed in the water.

Many lifeboats overturned while loading or lowering, spilling passengers into the sea; others were overturned by the ship's motion when they hit the water. It has been claimed[17] that some boats, due to the negligence of some officers, crashed down onto the deck, crushing other passengers, and sliding down towards the bridge. This has been refuted in various articles and by passenger and crew testimony.[18] Lusitania had 48 lifeboats, more than enough for all the crew and passengers, but only six were successfully lowered, all from the starboard side.

Despite Turner's efforts to beach the liner and reduce her speed, Lusitania no longer answered the helm. There was panic and disorder on the decks. Schwieger had been observing this through U-20's periscope, and by 14:25, he dropped the periscope and headed out to sea.[19]

Within six minutes, Lusitania's forecastle began to go under water. Her list continued to worsen and 10 minutes after the torpedoing, she had slowed enough to start putting boats in the water. On the port side, people panicked and got into the boats, even though they were swinging far in from the rails. On the starboard side, the boats were hanging several feet away from the sides. Crewmen would lose their grip on the falls—ropes used to lower the lifeboats—while trying to lower the boats into the ocean, and this caused the passengers from the boat to "spill into the sea like rag dolls." Others would tip on launch as some panicking people jumped into the boat. Of the 48 Lifeboats she carried, only 6 were launched successfully. A few of her collapsible lifeboats washed off her decks as she sank and provided refuge for many of those in the water.

Captain Turner remained on the bridge until the water rushed upward and destroyed the sliding door, washing him overboard into the sea. He took the ship's logbook and charts with him. He managed to escape the rapidly sinking Lusitania and find a chair floating in the water which he clung to. He was pulled unconscious from the water, and survived despite having spent 3 hours in the water. Lusitania's bow slammed into the bottom about 100 m (300 ft) below at a shallow angle due to her forward momentum as she sank. Along the way, some boilers exploded, including one that caused the third funnel to collapse; the remaining funnels snapped off soon after. Turner's last navigational fix had been only two minutes before the torpedoing, and he was able to remember the ship's speed and bearing at the moment of sinking. This was accurate enough to locate the wreck after the war. The ship travelled about two miles (3 km) from the time of the torpedoing to her final resting place, leaving a trail of debris and people behind.

Lusitania sank in 18 minutes, 8 miles (13 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale. 1,198 people died with her, including almost a hundred children.[20] The bodies of many of the victims were buried at either Lusitania's destination, Queenstown, or the Church of St. Multose in Kinsale, but the bodies of the remaining 884 victims were never recovered.

Political consequences

Schwieger was condemned in the Allied press as a war criminal.

Of the 139 US citizens aboard the Lusitania, 128 lost their lives, and there was massive outrage in Britain and America, The Nation calling it "a deed for which a Hun would blush, a Turk be ashamed, and a Barbary pirate apologize" and the British felt that the Americans had to declare war on Germany. However, US President Wilson refused to over-react. He said at Philadelphia on 10 May 1915:

There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right

The massive loss of life caused by the sinking of Lusitania required a definitive response from the US. When Germany had began its submarine campaign against Britain, Wilson had warned the US would hold the German government strictly accountable for any violations of American rights.

During the weeks after the sinking, the issue was hotly debated within the administration. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan urged compromise and restraint. The US, he believed, should try to persuade the British to abandon their interdiction of foodstuffs and limit their mine-laying operations at the same time as the Germans were persuaded to curtail their submarine campaign. He also suggested that the US government issue an explicit warning against US citizens travelling on any belligerent ships. Despite being sympathetic to Bryan's antiwar feelings, Wilson insisted that the German government must apologise for the sinking, compensate US victims, and promise to avoid any similar occurrence in the future.[21]

Wilson notes

Backed by State Department second-in-command Robert Lansing, Wilson made his position clear in three notes to the German government issued on 13 May, 9 June, and 21 July.

The first note affirmed the right of Americans to travel as passengers on merchant ships and called for the Germans to abandon submarine warfare against commercial vessels, whatever flag they sailed under.

In the second note Wilson rejected the German arguments that the British blockade was illegal, and was a cruel and deadly attack on innocent civilians, and their charge that the Lusitania had been carrying munitions. William Jennings Bryan considered Wilson's second note too provocative and resigned in protest after failing to moderate it, to be replaced by Robert Lansing who later said in his memoirs that following the tragedy he always had the "conviction that we would ultimately become the ally of Britain".

The third note, of 21 July, issued an ultimatum, to the effect that the US would regard any subsequent sinkings as "deliberately unfriendly".

On 19 August U-24 sank the White Star liner SS Arabic, with the loss of 44 passengers and crew, three of whom were American. The German government, while insisting on the legitimacy of its campaign against Allied shipping, disavowed the sinking of the Arabic; it offered an indemnity and pledged to order submarine commanders to abandon unannounced attacks on merchant and passenger vessels.[21]

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg persuaded the Kaiser to forbid action against ships flying neutral flags and the U-boat war was postponed once again on 27 August, as it was realised that British ships could easily fly neutral flags.[22]

There was disagreement over this move between the navy's admirals (headed by Alfred von Tirpitz) and Bethman-Hollweg. The Kaiser decided in favour of the Chancellor, backed by Army Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn, and Tirpitz and the head of the admiralty backed down. The German restriction order of 9 September 1915 stated that attacks were only allowed on ships that were definitely British, while neutral ships were to be treated under the Prize Law rules, and no attacks on passenger liners were to be permitted at all. The war situation demanded that there could be no possibility of orders being misinterpreted, and on 18 September Henning von Holtzendorff, the new head of the German Admiralty, issued a secret order: all U-boats operating in the English Channel and off the west coast of the United Kingdom were recalled, and the U-boat war would continue only in the North sea, where it would be conducted under the Prize Law rules.[22]

British propaganda

It was in the interests of the British to keep US passions inflamed, and a fabricated story was circulated that in some regions of Germany, schoolchildren were given a holiday to celebrate the sinking of the Lusitania. This story was so effective that James W. Gerard, the US ambassador to Germany, recounted it in his memoir of his time in Germany, Face to Face with Kaiserism (1918), though without substantiating its validity.[23]

Goetz medal

In August 1915, Munich medalist and sculptor Karl X. Goetz (1875-1950), who had produced a series of propagandist and satirical medals as a running commentary on the war, privately struck a small run of medals as a limited-circulation satirical attack (fewer than 500 were struck) on the Cunard Line for trying to continue business as usual during wartime. Goetz blamed both the British government and the Cunard Line for allowing the Lusitania to sail despite the German embassy's warnings.

One side of the medal showed the Lusitania sinking laden with guns (incorrectly depicted sinking stern first) with the motto "KEINE BANNWARE!" ("NO CONTRABAND!"), while the reverse showed a skeleton selling Cunard tickets with the motto "Geschäft Über Alles" ("Business Above All".)[24]

Goetz had put an incorrect date for the sinking on the medal, an error he later blamed on a mistake in a newspaper story about the sinking: instead of 7 May, he had put 5 May, two days before the actual sinking. Not realizing his error, Goetz made copies of the medal and sold them in Munich and also to some numismatic dealers with whom he conducted business.

The British Foreign Office obtained a copy of the medal, photographed it, and sent copies to the United states where it was published in the New York Times on 5 May 1916, the anniversary of the sinking.[25] Many popular magazines ran photographs of the medal, and it was falsely claimed that it had been awarded to the crew of the U-boat.[23]

British replica

The Goetz medal attracted so much attention that Lord Newton, who was in charge of Propaganda at the Foreign Office in 1916, decided to exploit the anti-German feelings aroused by it for propaganda purposes and asked department store entrepreneur Harry Gordon Selfridge to reproduce the medal.[26] The replica medals were produced in an attractive case claiming to be an exact copy of the German medal, and were sold for a shilling apiece. On the cases it was stated that the medals had been distributed in Germany "to commemorate the sinking of the Lusitania" and they came with a propaganda leaflet which strongly denounced the Germans and used the medal's incorrect date to claim that the sinking of the Lusitania was premeditated. The head of the Lusitania Souvenir Medal Committee later estimated that 250,000 were sold, proceeds being given to the Red Cross and St. Dunstan's Blinded Soldiers and Sailors Hostel.[27][28] Unlike the original Goetz medals which were stamped from bronze, the British copies were of diecast iron and were of poorer quality.[24]

Belatedly realizing his mistake, Goetz issued a corrected medal with the date of 7 May. The Bavarian government suppressed the medal and ordered their confiscation in April 1917. The original German medals can easily be distinguished from the English copies because the date is in German; the English version was altered to read 'May' rather than 'Mai'. After the war Goetz expressed his regret his work had been the cause of increasing anti-German feelings, but it remains one of the most celebrated propaganda acts of all time.

While the American public and leadership were not ready for war, the path to an eventual declaration of war had been set as a result of the sinking of the Lusitania.

Last living survivor

Audrey Lawson-Johnston (née Pearl) (born 1915) is the last living survivor of the RMS Lusitania sinking. She is widowed and resides in Bedfordshire, England.[2] Audrey became the last living survivor following the death of Barbara McDermott (nee Anderson) on 12 April 2008 and Ida Cantley on 31 December 2006. [3]

Controversies

Contraband and second explosion

Under the "cruiser rules", the Germans could sink a civilian vessel only after guaranteeing the safety of all the passengers. Since Lusitania (like all British merchantmen) was under instructions from the British Admiralty to report the sighting of a German submarine, and indeed to attempt to ram the ship if it surfaced to board and inspect her, she was acting as a naval auxiliary, and was thus exempt from this requirement and a legitimate military target. By international law, the presence (or absence) of military cargo was irrelevant.

Lusitania was in fact carrying small arms ammunition, which would not have been explosive.[29] Recent expeditions to the wreck have shown her holds are intact and show no evidence of internal explosion.

In 1993, Dr Robert Ballard, the famous explorer who discovered Titanic, conducted an in-depth exploration of the wreck of Lusitania. Ballard found Light had been mistaken in his identification of a gaping hole in the ship's side. To explain the second explosion, Ballard advanced the theory of a coal-dust explosion. He believed dust in the bunkers would have been thrown into the air by the vibration from the explosion; the resulting cloud would have been ignited by a spark, causing the second explosion. In the years since he first advanced this theory, it has been argued that this is nearly impossible. Critics of the theory say coal dust would have been too damp to have been stirred into the air by the torpedo impact in explosive concentrations; additionally, the coal bunker where the torpedo struck would have been flooded almost immediately by seawater flowing through the damaged hull plates.

More recently, marine forensic investigators have become convinced an explosion in the ship's steam-generating plant is a far more plausible explanation for the second explosion. There were very few survivors from the forward two boiler rooms, but they did report the ship's boilers did not explode; they were also under extreme duress in those moments after the torpedo's impact, however. Leading Fireman Albert Martin later testified he thought the torpedo actually entered the boiler room and exploded between a group of boilers, which was a physical impossibility. It is also known the forward boiler room filled with steam, and steam pressure feeding the turbines dropped dramatically following the second explosion. These point toward a failure, of one sort or another, in the ship's steam-generating plant. It is possible the failure came, not directly from one of the boilers in boiler room no. 1, but rather in the high-pressure steam lines to the turbines. Most researchers and historians agree that a steam explosion is a far more likely cause than clandestine high explosives for the second explosion.

The original torpedo damage alone, striking the ship on the starboard coal bunker of boiler room no. 1, would probably have sunk the ship without a second explosion. This first blast was enough to cause, on its own, serious off-center flooding. The deficiencies of the ship's original watertight bulkhead design exacerbated the situation, as did the many portholes which had been left open for ventilation.

Recent developments

The wreck of Lusitania is currently owned by New Mexico diver and businessman F. Gregg Bemis Jr.

In 1967 the wreck was sold by the Liverpool & London War Risks Insurance Association to former US Navy diver John Light, for £1,000. Bemis became a co-owner of the wreck in 1968, and by 1982 Bemis had bought out his partners to become sole owner. He subsequently went to court in England in 1986, the US in 1995, and Ireland in 1996 to ensure his ownership was legally watertight.[30][31]

None of the jurisdictions objected to his ownership of the vessel but in 1995 the Irish Government declared it a heritage site under the National Monuments Act, which prohibited him from in any way interfering with it or its contents. After a protracted legal wrangle, the Supreme Court in Dublin overturned the Arts and Heritage Ministry's previous refusal to issue Bemis with a five year exploration licence in 2007, ruling that the then minister for Arts and Heritage had misconstrued the law when he refused Bemis's 2001 application. Bemis planned to dive and recover and analyse whatever artifacts and evidence can help piece together the story of what happened to the ship. He says that any items found will be given to museums following analysis. Any fine art recovered, such as the Rubens rumoured to be on board, will remain in the ownership of the Irish Government.

In late July, 2008 Gregg Bemis was granted an "imaging" license by the Department of the Environment, which allows him to photograph and film the entire wreck, and should allow him to produce the first high-resolution pictures of it. Bemis plans to use the data gathered to assess the wreck's deterioration and to plan a strategy for a forensic examination of the ship, which he estimated would cost $5m. Florida-based Odyssey Marine Exploration (OME) have been contracted by Bemis to conduct the survey. The Department of the Environment's Underwater Archaeology Unit will join the survey team to ensure that research is carried out in a non-invasive manner. A film crew from the Discovery Channel will also be on hand. A documentary will be shown on the network in the next year.[32]

A dive team from Cork Sub Aqua Club, under license, made the first known discovery of munitions aboard in 2006. These include 15,000 rounds of .303 (7.7×56mmR) caliber rifle ammunition in boxes in the bow section of the ship. The .303 round was used by the British army in all of their battlefield rifles and machine guns. The find was photographed but left in situ under the terms of the license.[33]

Notes

- ↑ Atlantic Liners.

- ↑ http://www.thepeerage.com/p19065.htm

- ↑ The ship's overall length if often mis-quoted at either 785 or 790 feet. Please see http://www.atlanticliners.com/lusitania_home.htm#Anchor-Lusitani-33651 for further information.

- ↑ Lusitania, Atlantic Liner.

- ↑ Lost Liners.

- ↑ The Bromsgrove Society [1]

- ↑ Inquiry.

- ↑ Germany's second submarine campaign against the Allies during World War One was unrestricted in scope, as was submarine warfare during the Second World War.

- ↑ Patrick Beesly, Room 40: British Naval Intelligence 1914–1918 (1982) p.95; Preston (2002), pp76–77

- ↑ http://www.fas.org/irp/ops/ci/docs/ci1/notice.jpg

- ↑ http://www.dowfamilyhistory.co.uk/body_lusitania.html

- ↑ Preston, Diana. Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy. New York: Walker & Company, 2002. 184.

- ↑ Lusitania (1907-1915), The Great Ocean Liners.

- ↑ Des Hickey and Gus Smith, Seven Days to Disaster: The Sinking of the Lusitania, 1981, William Collins, ISBN 0-00-216882-0

- ↑ Preston, pp. 416-419.

- ↑ Report.

- ↑ Linnihan, Ellen (2005). Stranded at Sea. Saddleback Educational Publications. pp. p. 32. ISBN 1562548301.

- ↑ Schapiro, Amy; Thomas H. Kean (2003). Millicent Fenwick. Rutgers University Press. pp. pp. 21-22. ISBN 0813532310.

- ↑ The Sinking of the Lusitania: Terror at Sea or ("Lusitania: Murder on the Atlantic") puts this at 14:30, two minutes after Lusitania sank.

- ↑ Robert Ballard, Exploring the Lusitania. This number is cited, probably to include the German spies detained below decks. Afterwards, the Cunard line offered local fishermen and sea merchants a cash reward for the bodies floating all throughout the Irish Sea, some floating as far away as the Welsh coast. In all, only 289 bodies were recovered, 65 of which were never identified. The Cunard Steamship Company announced the official death toll of 1,195 on 1 March 1916.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Zieger, Robert H. (1972). America's Great War. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. pp. 24-25. ISBN 0847696456.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gardiner, Robert; Randal Gray, Przemyslaw Budzbon (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906-1921. Conway. pp. p. 137. ISBN 0851772455.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Quinn, Patrick J. (2001). The Conning of America. Rodopi. pp. p. 54-55. ISBN 904201475X.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Burns, G. (2003). "Excerpt from The Lusitania Medal and its Varieties". LusitaniaMedal.com.

- ↑ White, Horace (5 May 1916), "More Schrectlichkeit", New York Times: p. 10, http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9401E7DB113FE233A25756C0A9639C946796D6CF

- ↑ Cull, Nicholas John; David Holbrook Culbert, David Welch (2003). Propaganda and Mass Persuasion. ABC-CLIO. pp. p. 124. ISBN 1576078205.

- ↑ Ponsonby, Arthur (2005). Falsehood in War Time: Containing an Assortment of Lies Circulated Throughout the Nations During the Great War. Kessinger Publishing. pp. pp. 124-125. ISBN 1417924217.

- ↑ Besly, Edward (1997). Loose Change. National Museum of Wales. pp. p. 55. ISBN 0720004446. (Original propaganda leaflet)

- ↑ Included in this cargo were 4,200,000 rounds of Remington 0.303 rifle cartridges, 1250 cases of 3 inch (76 mm) fragmentation shells, and eighteen cases of fuses. (All were listed on the ship's two-page manifest, filed with U.S. Customs after she departed New York on 1 May.) However, the materials listed on the cargo manifest were small arms and the physical size of this cargo would have been quite small. These munitions were also proven to be non-explosive in bulk, and were clearly marked as such. It was perfectly legal under American shipping regulations for her to carry these; experts agreed they were not to blame for the second explosion. Allegations the ship was carrying more controversial cargo, such as fine aluminium powder, concealed as cheese on her cargo manifests, have never been proven.

- ↑ Rogers, Paul (March/April 2005). "How Deep Is His Love". Stanford Magazine. Stanford Alumni Association.

- ↑ Sharrock, David (2 April, 2007), "Millionaire diver wins right to explore wreck of the Lusitania", The Times, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article1599972.ece

- ↑ Shortall, Eithne (20 July 2008), "Riddle of Lusitania sinking may finally be solved", The Times, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/ireland/article4364701.ece

- ↑ Goodwin Sides, Anne (2008-11-22). "New Clues In Lusitania's Sinking", National Public Radio.

References

- Thomas A. Bailey. "The Sinking of the Lusitania," The American Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Oct 1935), pp. 54–73 in JSTOR

- Thomas A. Bailey; Paul B. Ryan. The Lusitania Disaster: An Episode in Modern Warfare and Diplomacy (1975)

- Ballard, Robert D., & Dunmore, Spencer. (1995). Exploring the Lusitania. New York: Warner Books.

- Hoehling, A.A. and Mary Hoehling. (1956). The Last Voyage of the Lusitania. Maryland: Madison Books.

- Layton, J. Kent (2007). Lusitania: An Illustrated Biography of the Ship of Splendor.

- Layton, J. Kent (2005). Atlantic Liners: A Trio of Trios. CafePress Publishing.

- Ljungström, Henrik. Lusitania. The Great Ocean Liners.

- O'Sullivan, Patrick. (2000). The Lusitania: Unravelling the Mysteries. New York: Sheridan House.

- Preston, Diana. (2002). Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy. Waterville: Thorndike Press. Preston (2002 p 384)

- The Sunday Times, (2008) "Is The Riddle of The Lusitania About to be Solved?" [4]

Further reading

- Thomas A. Bailey, "German Documents Relating to the 'Lusitania'", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Sep., 1936), pp. 320–37 in JSTOR

- Timeline, The Lusitania Resource.

- Facts and Figures, The Lusitania Resource.

External links

- The Home Port of RMS Lusitania Lusitania.net

- CWGC record of Lt. Robert Matthews {Lusitania Passenger} {Reference only}

- Clydebank Restoration Trust {Clydebank social and architectural history }

- Professor Joseph Marichal {Lusitania Passenger KIA WWI} {Reference only}

- British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry

- Lest We Forget Moving Passenger's Stories from the Lusitania

- Lusitania Home at Atlantic Liners.com

- Lusitania Information & photos

- Lusitania Passenger Stories

- Passport to Perdition The tragic story of Lusitania victim Thoms Silva.

- The Lusitania Memorial in Cobh

- Maritimequest RMS Lusitania Photo Gallery

- Photo of one of the Lusitania's salvaged propellers at Liverpool Maritime Museum

- The Fast Lusitania

- Welsh ballad about the sinking of the Lusitania

- 9/14/1907;The New 25 1/2 Knot Cunard Turbine Liner Lusitania

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Kaiserin Auguste Victoria |

World's largest passenger ship 1907 |

Succeeded by Mauretania |

| Preceded by Deutschland |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound) 1907–1909 |

|

| Preceded by Kaiser Wilhelm II |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Eastbound) 1907 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||