Quechua

| Quechua Qhichwa Simi / Runa Shimi / Runa Simi |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | ['qʰeʃ.wa 'si.mi] ['χetʃ.wa 'ʃi.mi] [kitʃ.wa 'ʃi.mi] [ʔitʃ.wa 'ʃi.mi] ['ɾu.nɑ 'si.mi] | |

| Spoken in: | Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. | |

| Region: | Andes | |

| Total speakers: | 10.4 million | |

| Ranking: | 65 | |

| Language family: | Quechuan Quechua |

|

| Writing system: | Latin alphabet | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | Bolivia and Peru. | |

| Regulated by: | Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | qu | |

| ISO 639-2: | que | |

| ISO 639-3: | que – Quechua (generic) many varieties of Quechua have their own codes. |

|

with major to minor Quechua-speaking regions. |

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Quechua (Runa Simi) is a Native American language of South America. It was already widely spoken across the Central Andes long before the time of the Incas, who established it as the official language of administration for their Empire, and is still spoken today in various regional forms (the so-called ‘dialects’) by some 10 million people through much of South America, including Peru, south-western and central Bolivia, southern Colombia and Ecuador, north-western Argentina and northern Chile. It is the most widely spoken language of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Though it is traditionally referred to as a single language, many (if not most) linguists treat it as a family of related languages - Quechuan languages, with approximately 46 dialects, grouped in at least seven languages.[1] [2] [3]

Quechua is a very regular agglutinative language, as opposed to a fusional one. Its normal sentence order is SOV (subject-object-verb). Its large number of suffixes changes both the overall significance of words and their subtle shades of meaning. Notable grammatical features include bipersonal conjugation (verbs agree with both subject and object), evidentiality (indication of the source and veracity of knowledge), a topic particle, and suffixes indicating who benefits from an action and the speaker's attitude toward it.

Contents |

History

The various dialects of Quechua were widely spoken throughout the Andes long before the rise of the Inca state in the 15th century. The Incas made one dialect of Quechua (Classical Quechua, the ancestor of Southern Quechua) their official language; as they expanded their empire by conquest, this dialect became pre-Columbian Peru's lingua franca, retaining this status after the Spanish conquest in the 16th century.

The oldest records of the language are those of Fray Domingo de Santo Tomás, who arrived in Peru in 1538 and learned the language from 1540, publishing his Grammatica o arte de la lengua general de los indios de los reynos del Perú in 1560.

Quechua has often been grouped with Aymara as a larger Quechumaran linguistic stock, largely because about a third of its vocabulary is shared with Aymara. This proposal is controversial, however, as the cognates are close, often closer than intra-Quechua cognates, and there is little relationship in the affixal system. The similarities may be due to long-term contact rather than from common origin. The language was further extended beyond the limits of the Inca empire by the Roman Catholic Church, which chose it to preach to natives in the Andes. Where the two languages intermix, Quechua phrases and words are commonly used by Spanish speakers and vice-versa. In southern rural Bolivia, for instance, many Quechua words such as wawa (infant), michi (cat), wasca (strap, or thrashing) are as commonly used as their Spanish counterparts, even in entirely Spanish-speaking areas.

Today, it has the status of an official language in both Peru and Bolivia, along with Spanish and Aymara. Before the arrival of the Spaniards and the introduction of the Latin alphabet, Quechua had no written alphabet. The Incas kept track of numerical data through a system of quipu (knotted strings).

Currently, the major obstacle to the diffusion of the usage and teaching of Quechua is the lack of written material in the Quechua language, namely books, newspapers, software, magazines, etc. Thus, Quechua, along with Aymara and the minor indigenous languages, remains essentially an oral language. It must be said that this situation is being greatly improved by modern technology.

Geographic distribution

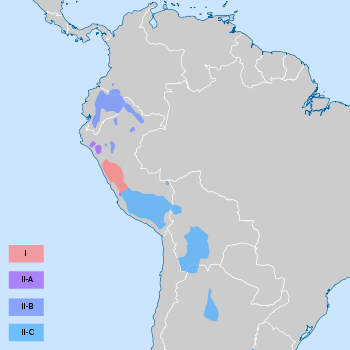

There are four main branches:

Quechua I or Waywash is spoken in Peru's central highlands. It is the most diverse branch of Quechua,[4] such that its dialects have often been considered different languages.

Quechua II or Wanp'una (Traveler) is divided into three branches:

- II-A: Yunkay Quechua is spoken sporadically in Peru's occidental highlands;

- II-B: Northern Quechua (also known as Runashimi or, especially in Ecuador, Kichwa) is mainly spoken in Colombia and Ecuador. It is also spoken in the Amazonian lowlands in Ecuador and Peru;

- II-C: Southern Quechua, spoken in Peru's southern highlands, Bolivia, Argentina and Chile, is today's most important branch because it has the largest number of speakers and because of its cultural and literary legacy.

This traditional classification, though still a helpful guide, has been increasingly challenged in recent years, since a number of regional varieties of Quechua seem to be intermediate between the two branches.

Number of speakers

The number of speakers given varies widely according to the sources. The most reliable figures are to be found in the census results of Peru (1993) and Bolivia (2001), though they are probably altogether too low due to underreporting. The 2001 Ecuador census seems to be a prominent example of underreporting, as it comes up with only 499,292 speakers of the two varieties Quichua and Kichwa combined, where other sources estimate between 1.5 and 2.2 million speakers.

- Argentina: 100,000

- Bolivia: 2,100,000 (2001 census)

- Brazil: unknown

- Chile: very few, spoken in pockets in the Chilean Altiplano (Ethnologue)

- Colombia: 9,000 (Ethnologue)

- Ecuador: 500,000 to 1,000,000

- Peru: 3,200,000 (1993 census)

Additionally, there may be hundreds of thousands of speakers outside the traditionally Quechua speaking territories, in immigrant communities.

Vocabulary

A number of Quechua loanwords have entered English via Spanish, including coca, cóndor, guano, jerky, llama, pampa, puma, quinine, quinoa, vicuña and possibly gaucho. The word lagniappe comes from the Quechua word yapay ("to increase; to add") with the Spanish article la in front of it, la yapa or la ñapa in Spanish.

The influence on Latin American Spanish includes such borrowings as papa for "potato", chuchaqui for "hangover" in Ecuador, and diverse borrowings for "altitude sickness", in Bolivia from Quechua suruqch'i to Bolivian sorojchi, in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru soroche.

Quechua has borrowed a large number of Spanish words, such as pero (from pero, but), bwenu (from bueno, good), and burru (from burro, donkey).

Phonology

The description below applies to Cusco dialect; there are significant differences in other varieties of Quechua.

Vowels

Quechua uses only three vowels: /a/ /i/ and /u/, as in Aymara (including Jaqaru). Monolingual speakers pronounce these as [æ] [ɪ] and [ʊ] respectively, though the Spanish vowels /a/ /i/ and /u/ may also be used. When the vowels appear adjacent to the uvular consonants /q/, /qʼ/, and /qʰ/, they are rendered more like [ɑ], [ɛ] and [ɔ] respectively.

Consonants

| labial | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | uvular | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosive / affricate | p | t | tʃ | k | q | ||

| aspirated plosive or affricate | pʰ | tʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | qʰ | ||

| ejective | p’ | t’ | tʃ’ | k’ | q’ | ||

| fricative | s | h | |||||

| nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||

| lateral approximant | l | ʎ | |||||

| flap | ɾ | ||||||

| central approximant | j | w |

None of the plosives or fricatives are voiced; voicing is not phonemic in the Quechua native vocabulary of the modern Cusco variety.

About 30% of the modern Quechua vocabulary is borrowed from Spanish, and some Spanish sounds (e.g. f, b, d, g) may have become phonemic, even among monolingual Quechua speakers.

Writing system

Quechua has been written using the Roman alphabet since the Spanish conquest of Peru. However, written Quechua is not utilized by the Quechua-speaking people at large due to the lack of printed referential material in Quechua.

Until the 20th century, Quechua was written with a Spanish-based orthography. Examples: Inca, Huayna Cápac, Collasuyo, Mama Ocllo, Viracocha, quipu, tambo, condor. This orthography is the most familiar to Spanish speakers, and as a corollary, has been used for most borrowings into English.

In 1975, the Peruvian government of Juan Velasco adopted a new orthography for Quechua. This is the writing system preferred by the Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua. Examples: Inka, Wayna Qapaq, Qollasuyu, Mama Oqllo, Wiraqocha, khipu, tampu, kuntur. This orthography:

- uses w instead of hu for the /w/ sound.

- distinguishes velar k from uvular q, where both were spelled c or qu in the traditional system.

- distinguishes simple, ejective, and aspirated stops in dialects (such as that of Cuzco) which have them — thus khipu above.

- continues to use the Spanish five-vowel system.

In 1985, a variation of this system was adopted by the Peruvian government; it uses the Quechua three-vowel system. Examples: Inka, Wayna Qapaq, Qullasuyu, Mama Uqllu, Wiraqucha, khipu, tampu, kuntur.

The different orthographies are still highly controversial in Peru. Advocates of the traditional system believe that the new orthographies look too foreign, and suggest that it makes Quechua harder to learn for people who have first been exposed to written Spanish. Those who prefer the new system maintain that it better matches the phonology of Quechua, and point to studies showing that teaching the five-vowel system to children causes reading difficulties in Spanish later on.

For more on this, see Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift.

Writers differ in the treatment of Spanish loanwords. Sometimes these are adapted to the modern orthography, and sometimes they are left in Spanish. For instance, "I am Robert" could be written Robertom kani or Ruwirtum kani. (The -m is not part of the name; it is an evidential suffix.)

Peruvian linguist Rodolfo Cerrón-Palomino has proposed an orthographic norm for all Quechua, called Southern Quechua. This norm, el Quechua estándar or Hanan Runasimi, which is accepted by many institutions in Peru, has been made by combining conservative features of two common dialects: Ayacucho Quechua and Qusqu-Qullaw Quechua (spoken in Cusco, Puno, Bolivia, and Argentina). For instance:

| Ayacucho | Cusco | Southern Quechua | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| upyay | uhyay | upyay | "to drink" |

| utqa | usqha | utqha | "fast" |

| llamkay | llank'ay | llamk'ay | "to work" |

| ñuqanchik | nuqanchis | ñuqanchik | "we (inclusive)" |

| -chka- | -sha- | -chka- | (progressive suffix) |

| punchaw | p'unchay | p'unchaw | "day" |

To listen to recordings of these and many other words as pronounced in many different Quechua-speaking regions, see the external website The Sounds of the Andean Languages. There is also a full section on the new Quechua and Aymara Spelling.

Grammar

Pronouns

| Number | |||

| Singular | Plural | ||

| Person | First | Ñuqa | Ñuqanchik (inclusive)

Ñuqayku (exclusive) |

| Second | Qam | Qamkuna | |

| Third | Pay | Paykuna | |

In Quechua, there are seven pronouns. Quechua has two first person plural pronouns ("we", in English). One is called the inclusive, which is used when the speaker wishes to include in "we" the person to whom he or she is speaking ("we and you"). The other form is called the exclusive, which is used when the addressee is excluded. ("we without you"). Quechua also adds the suffix -kuna to the second and third person singular pronouns qam and pay to create the plural forms qam-kuna and pay-kuna.

Adjectives

Adjectives in Quechua are always placed before nouns. They lack gender and number, and are not declined to agree with substantives.

Numbers

- Cardinal numbers. ch'usaq (0), huk (1), iskay (2), kimsa (3), tawa (4), pichqa (5), suqta (6), qanchis (7), pusaq (8), isqun (9), chunka (10), chunka hukniyuq (11), chunka iskayniyuq (12), iskay chunka (20), pachak (100), waranqa (1,000), hunu (1,000,000), lluna (1,000,000,000,000).

- Ordinal numbers. To form ordinal numbers, the word ñiqin is put after the appropriate cardinal number (e.g., iskay ñiqin = "second"). The only exception is that, in addition to huk ñiqin ("first"), the phrase ñawpaq is also used in the somewhat more restricted sense of "the initial, primordial, the oldest".

Nouns

Noun roots accept suffixes which indicate person (defining of possession, not identity), number, and case. In general, the personal suffix precedes that of number - in the Santiago del Estero variety, however, the order is reversed.[5] From variety to variety, suffixes may change.

| Function | Suffix | Example | (translation) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| suffix indicating number | plural | -kuna | wasikuna | houses |

| possessive suffix | 1.person singular | -y, -: | wasiy, wasii | my house |

| 2.person singular | -yki | wasiyki | your house | |

| 3.person singular | -n | wasin | his/her/its house | |

| 1.person plural (incl) | -nchik | wasinchik | our house (incl.) | |

| 1.person plural (excl) | -y-ku | wasiyku | our house (excl.) | |

| 2.person plural | -yki-chik | wasiykichik | your (pl.) house | |

| 3.person plural | -n-ku | wasinku | their house | |

| suffixes indicating case | nominative | - | wasi | the house (subj.) |

| accusative | -(k)ta | wasita | the house (obj.) | |

| comitative (instrumental) | -wan | wasiwan | with the house | |

| abessive | -naq | wasinaq | without the house | |

| dative | -paq | wasipaq | to the house | |

| genitive | -p(a) | wasip(a) | of the house | |

| causative | -rayku | wasirayku | because of the house | |

| benefactive | -paq | wasipaq | for the house | |

| locative | -pi | wasipi | at the house | |

| directional | -man | wasiman | towards the house | |

| inclusive | -piwan, puwan | wasipiwan, wasipuwan | including the house | |

| terminative | -kama, -yaq | wasikama, wasiyaq | up to the house | |

| transitive | -(rin)ta | wasinta | through the house | |

| ablative | -manta, -piqta | wasimanta, wasipiqta | off/from the house | |

| adessive | -(ni)ntin | wasintin | the house (obj.) | |

| immediate | -raq | wasiraq | first the house | |

| interactive | -pura | wasipura | among the houses | |

| exclusive | -lla(m) | wasilla(m) | only the house | |

| comparative | -naw, -hina | wasinaw, wasihina | than the house | |

Adverbs

Adverbs can be formed by adding -ta or, in some cases, -lla to an adjective: allin - allinta ("good - well"), utqay - utqaylla ("quick - quickly"). They are also formed by adding suffixes to demonstratives: chay ("that") - chaypi ("there"), kay ("this") - kayman ("hither").

There are several original adverbs. For Europeans, it is striking that the adverb qhipa means both "behind" and "future", whereas ñawpa means "ahead, in front" and "past".[6] This means that local and temporal concepts of adverbs in Quechua (as well as in Aymara) are associated to each other reversely compared to European languages. For the speakers of Quechua, we are moving backwards into the future (we cannot see it - ie. it is unknown), facing the past (we can see it - ie. we remember it).

Verbs

The infinitive forms (unconjugated) have the suffix -y (much'a= "kiss"; much'a-y = "to kiss"). The endings for the indicative are:

| Present | Past | Future | Pluperfect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ñuqa | -ni | -rqa-ni | -saq | -sqa-ni |

| Qam | -nki | -rqa-nki | -nki | -sqa-nki |

| Pay | -n | -rqa(-n) | -nqa | -sqa |

| Ñuqanchik | -nchik | -rqa-nchik | -su-nchik | -sqa-nchik |

| Ñuqayku | -yku | -rqa-yku | -saq-ku | -sqa-yku |

| Qamkuna | -nki-chik | -rqa-nki-chik | -nki-chik | -sqa-nki-chik |

| Paykuna | -n-ku | -rqa-(n)ku | -nqa-ku | -sqa-ku |

To these are added various suffixes to change the meaning. For example, -chi is a causative and -ku is a reflexive (example: wañuy = "to die"; wañuchiy = to kill wañuchikuy = "to commit suicide"); -naku is used for mutual action (example: marq'ay= "to hug"; marq'anakuy= "to hug each other"), and -chka is a progressive, used for an ongoing action (e.g., mikhuy = "to eat"; mikhuchkay = "to be eating").

Grammatical particles

Particles are indeclinable, that is, they do not accept suffixes. They are relatively rare. The most common are arí ("yes") and mana ("no"), although mana can take some suffixes, such as -n/-m (manan/manam), -raq (manaraq, not yet) and -chu (manachu?, or not?), to intensify the meaning. Also used are yaw ("hey", "hi"), and certain loan words from Spanish, such as piru (from Spanish pero "but") and sinuqa (from sino "rather").

Evidentiality

Nearly every Quechua sentence is marked by an evidential suffix, indicating how certain the speaker is about a statement. -mi expresses personal knowledge (Tayta Wayllaqawaqa chufirmi, "Mr. Huayllacahua is a driver-- I know it for a fact"); -si expresses hearsay knowledge (Tayta Wayllaqawaqa chufirsi, "Mr. Huayllacahua is a driver, or so I've heard"); -chá expresses probability (Tayta Wayllaqawaqa chufirchá, "Mr. Huayllacahua is a driver, most likely"). These become -m, -s, -ch after a vowel, although -ch is rarely used, and the majority of speakers usually employ -chá, even after a vowel (Mariochá, "He's Mario, most likely").

The evidential suffixes are not restricted to nouns; they can attach to any word in the sentence, typically the comment (that is, new information, as opposed to the topic).

In popular culture

- The fictional Huttese language in the Star Wars movies is largely based upon Quechua. According to Jim Wilce, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Northern Arizona University, George Lucas contacted a colleague of his, Allen Sonafrank, to record the dialogue. Wilce and Sonafrank discussed the matter, and felt it might be demeaning to have an alien represent Quechuans, especially in light of Erich von Daniken's popular publications that claimed Inca monuments were created by aliens because "primitives" like the Incas could never have produced them. Sonafrank declined, but a grad student, who could pronounce but did not speak Quechua, recorded Jabba's dialogue. There are reports that the dialogue was played backwards or remixed, possibly to avoid offending Quechuans.

- The president of Ecuador, Rafael Correa, speaks fluent Quechua.

- The sport retailer Decathlon Group brands their mountain equipment range as Quechua.

- In "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" Indy has a dialogue in Quechua with Peruvians. He explains he learned the language with Pancho Villa.

See also

- Aymara language

- Andes

- List of English words of Quechuan origin

- South Bolivian Quechua

Notes

- ↑ Torero, Alfredo (1983), "La familia lingûística quechua", América Latina en sus lenguas indígenas, Caracas: Monte Ávila, ISBN 9233019268

- ↑ Torero, Alfredo (1974), El quechua y la historia social andina, Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma, Dirección Universitaria de Investigación, ISBN 9786034502109

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Quechuan (SIL)

- ↑ Lyle Campbell, American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 189

- ↑

- ↑ This is not unknown in English, where "before" means "in the past", and Shakespeare's Macbeth says "The greatest is behind", meaning in the future.

References

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. Lingüística Quechua, Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos 'Bartolomé de las Casas', 2nd ed. 2003

- Cole, Peter. "Imbabura Quechua", North-Holland (Lingua Descriptive Studies 5), Amsterdam 1982.

- Cusihuamán, Antonio, Diccionario Quechua Cuzco-Collao, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos "Bartolomé de Las Casas", 2001, ISBN 9972691365

- Cusihuamán, Antonio, Gramática Quechua Cuzco-Collao, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos "Bartolomé de Las Casas", 2001, ISBN 9972691373

- Mannheim, Bruce, The Language of the Inka since the European Invasion, University of Texas Press, 1991, ISBN 0292746636

- Rodríguez Champi, Albino. (2006). Quechua de Cusco. Ilustraciones fonéticas de lenguas amerindias, ed. Stephen A. Marlett. Lima: SIL International y Universidad Ricardo Palma. [1]

Further reading

- Adelaar, Willem F. H. Tarma Quechua: Grammar, Texts, Dictionary. Lisse: Peter de Ridder Press, 1977.

- Bills, Garland D., Bernardo Vallejo C., and Rudolph C. Troike. An Introduction to Spoken Bolivian Quechua. Special publication of the Institute of Latin American Studies, the University of Texas at Austin. Austin: Published for the Institute of Latin American Studies by the University of Texas Press, 1969. ISBN 0292700199

- Curl, John, Ancient American Poets. Tempe AZ: Bilingual Press, 2005.ISBN 1-931010-21-8 http://red-coral.net/Pach.html

- Gifford, Douglas. Time Metaphors in Aymara and Quechua. St. Andrews: University of St. Andrews, 1986.

- Harrison, Regina. Signs, Songs, and Memory in the Andes: Translating Quechua Language and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989. ISBN 0292776276

- Jake, Janice L. Grammatical Relations in Imbabura Quechua. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Garland Pub, 1985. ISBN 082405475X

- King, Kendall A. Language Revitalization Processes and Prospects: Quichua in the Ecuadorian Andes. Bilingual education and bilingualism, 24. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters LTD, 2001. ISBN 1853594954

- King, Kendall A., and Nancy H. Hornberger. Quechua Sociolinguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2004.

- Lara, Jesús, Maria A. Proser, and James Scully. Quechua Peoples Poetry. Willimantic, Conn: Curbstone Press, 1976. ISBN 0915306093

- Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. Mixed Categories: Nominalizations in Quechua. Studies in natural language and linguistic theory, [v. 11]. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1988. ISBN1556080506

- Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. Relative Clauses in Cuzco Quechua: Interactions between Core and Periphery. Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University Linguistics Club, 1982.

- Muysken, Pieter. Syntactic Developments in the Verb Phrase of Ecuadorian Quechua. Lisse: Peter de Ridder Press, 1977. ISBN 9031601519

- Nuckolls, Janis B. Sounds Like Life: Sound-Symbolic Grammar, Performance, and Cognition in Pastaza Quechua. Oxford studies in anthropological linguistics, 2. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN

- Parker, Gary John. Ayacucho Quechua Grammar and Dictionary. Janua linguarum. Series practica, 82. The Hague: Mouton, 1969.

- Sánchez, Liliana. Quechua-Spanish Bilingualism: Interference and Convergence in Functional Categories. Language acquisition & language disorders, v. 35. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub, 2003. ISBN 1588114716

- Weber, David. A Grammar of Huallaga (Huánuco) Quechua. University of California publications in linguistics, v. 112. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989. ISBN 0520097327

- Wright, Ronald, and Nilda Callañaupa. Quechua Phrasebook. Hawthorn, Vic., Australia: Lonely Planet, 1989. ISBN 0864420390

External links

- El Quechua de Santiago del Estero, extensive site covering the grammar of Argentinian Quechua (in Spanish)

- runasimi.de Multilingual Quechua website with online dictionary (xls) Quechua - German - English - Spanish.

- Quechua Language and Linguistics an extensive site.

- The Sounds of the Andean Languages listen online to pronunciations of Quechua words, see photos of speakers and their home regions, learn about the origins and varieties of Quechua.

- CyberQuechua, by the Quechua-speaking linguist Serafín Coronel Molina.

- Multilingual Dictionary: Spanish - Quechua (Cusco, Ayacucho, Junín, Ancash) - Aymara

- Toponimos del Quechua de Yungay, Peru

- Sacred Hymns of Pachacutec

- Quechua Network's Dictionary a very good one.

- Quechua lessons (www.andes.org) in Spanish and English

- Quechua course in Spanish, by Demetrio Tupah Yupanki (Red Científica Peruana)

- Detailed map of the varieties of Quechua according to SIL (fedepi.org)

- Quechua - English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary - the Rosetta Edition.

- Ecuadorian Quechua - English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary - the Rosetta Edition.

- Google Quechua

- 5 Quechua dictionaries online

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||