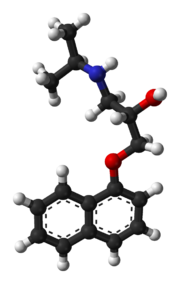

Propranolol

|

|

|

|

|

Propranolol

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 1-(isopropylamino)- 3-(naphthalen-1-yloxy)propan-2-ol |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | C07 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C16H21NO2 |

| Mol. mass | 259.34 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 26% |

| Metabolism | hepatic (extensive) |

| Half life | 4-5 hours |

| Excretion | renal <1% |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Licence data |

|

| Pregnancy cat. | |

| Legal status | |

| Routes | oral, iv |

Propranolol (INN) is a non-selective beta blocker mainly used in the treatment of hypertension. It was the first successful beta blocker developed. It is the only drug proven effective for the prophylaxis of migraines in children. Propranolol is available in generic form as propranolol hydrochloride, as well as an AstraZeneca and Wyeth product under the trade names Inderal, Inderal LA, Avlocardyl, Deralin, Dociton, Inderalici, InnoPran XL, Sumial (depending on marketplace and release rate).

Contents |

History and development

Scottish scientist and St. Andrews graduate James W. Black successfully developed propranolol in the late 1950s. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery in 1988. Propranolol was derived from the early β-adrenergic antagonists dichloroisoprenaline and pronethalol. The key structural modification, which was carried through to essentially all subsequent beta blockers, was the insertion of an oxymethylene bridge into the arylethanolamine structure of pronethalol thus greatly increasing the potency of the compound. This also apparently eliminated the carcinogenicity found with pronethalol in animal models.

Pharmacology

Propranolol is a non-selective beta blocker, that is, it blocks the action of epinephrine on both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. It has little intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA) but has strong membrane stabilizing activity (only at high blood concentrations, eg overdosage). Only L-propranolol is a powerful adrenoceptor antagonist, whereas D-propranolol is not. However, both have local anesthetic (termed topical) effect.

Pharmacokinetics

Propranolol is rapidly and completely absorbed, with peak plasma levels achieved approximately 1–3 hours after ingestion. Co-administration with food appears to enhance bioavailability. Despite complete absorption, propranolol has a variable bioavailability due to extensive first-pass metabolism. Hepatic impairment will therefore increase its bioavailability. The main metabolite 4-hydroxypropranolol, with a longer half-life (5.2–7.5 hours) than the parent compound (3–4 hours), is also pharmacologically active.

Propranolol is a highly lipophilic drug achieving high concentrations in the brain. The duration of action of a single oral dose is longer than the half-life and may be up to 12 hours, if the single dose is high enough (e.g., 80 mg). Effective plasma concentrations are between 10–100 ng/mL.

Toxic levels are associated with plasma concentrations above 2000 ng/ml

Clinical use

Indications

Propranolol is indicated for the management of various conditions including:[1]

- Hypertension

- Angina pectoris

- Tachyarrhythmias

- Myocardial infarction

- Control of tachycardia/tremor associated with anxiety and hyperthyroidism and lithium therapy. There has been some experimentation in psychiatric areas:[2] with treating the excessive drinking of fluids in psychogenic polydipsia,[3][4] antipsychotic-induced akathisia,[5] and aggressive behavior of patients with brain-injuries.[6]

- Essential tremor

- Migraine prophylaxis

- Cluster Headaches prophylaxis

- Tension headache (Off the label use)

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Phaeochromocytoma (along with α blocker)

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (experimental)

- Glaucoma

While once first-line treatment for hypertension, the role for beta-blockers was downgraded in June 2006 in the United Kingdom to fourth-line as they perform less well than other drugs, particularly in the elderly, and evidence is increasing that the most frequently used beta-blockers at usual doses carry an unacceptable risk of provoking type 2 diabetes. [7]

Propranolol is also used to lower portal vein pressure in portal hypertension and prevent oesophageal variceal bleeding.

Propranolol is often used by musicians and other performers to prevent stage fright.

Propranolol is currently being investigated as a potential treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. [8][9][10]

Precautions/contraindications

Propranolol should be used with caution in patients with:[1]

- Diabetes mellitus or hyperthyroidism, since signs and symptoms of hypoglycaemia may be masked. Also, propranolol may affect blood sugar levels

- Peripheral vascular disease and Raynaud's syndrome, which may be exacerbated

- Phaeochromocytoma, as hypertension may be aggravated without prior alpha blocker therapy

- Myasthenia gravis, may be worsened

- Other drugs with bradycardic effects

Propranolol is contraindicated in patients with:[1]

- Reversible airways disease, particularly asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Bradycardia (<50 beats/minute)

- Sick sinus syndrome

- Atrioventricular block (second or third degree)

- Shock

- Severe hypotension

- Uncontrolled congestive heart failure

- Cocaine toxicity [per American Heart Association guidelines, 2005]

Adverse effects

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with propranolol therapy are similar to other lipophilic beta blockers (see beta blocker).

Pregnancy and lactation

Propranolol, like other beta blockers, is classified as Pregnancy category C in the United States and ADEC Category C in Australia. Beta-blocking agents in general reduce perfusion of the placenta which may lead to adverse outcomes for the neonate, including pulmonary or cardiac complications, or premature birth. The newborn may experience additional adverse effects such as hypoglycemia and bradycardia.

Most beta-blocking agents appear in the milk of lactating women. This is especially the case for a lipophilic drug like propranolol. Breastfeeding is not recommended in patients receiving propranolol therapy.

Interactions

Beta blockers, including propranolol, have an additive effect with other drugs which decrease blood pressure, or which decrease cardiac contractility or conductivity. Clinically-significant interactions particularly occur with:[1]

- verapamil

- epinephrine

- β2-adrenergic receptor agonists

- clonidine

- ergot alkaloids

- isoprenaline

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- quinidine

- cimetidine

- lidocaine

- phenobarbital

- rifampicin

Dosage

The usual maintenance dose ranges for oral propranolol therapy vary by indication:

- Hypertension, angina, essential tremor

- 120–320 mg daily in divided doses.

- Sustained-release formulations are available in some markets.

- Tachyarrhythmia, anxiety, hyperthyroidism

- 10–40 mg 3–4 times daily

Intravenous (IV) propranolol may be used in acute arrhythmia or thyrotoxic crisis.[11]

Research into role against malaria

Propranolol along with a number of other membrane-acting drugs have been investigated for possible effects on P. falciparum and so the treatment of malaria. In vitro positive effects until recently had not been matched by useful in vivo anti-parasite activity against P. vinckei,[12] or P. yoelii nigeriensis.[13] However a single study from 2006 has suggested that propranolol may reduce the dosages required for existing drugs to be effective against P. falciparum by 5- to 10-fold, suggesting a role for combination therapies.[14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ↑ Kornischka J, Cordes J, Agelink MW (April 2007). "[40 years beta-adrenoceptor blockers in psychiatry]" (in German). Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 75 (4): 199–210. doi:. PMID 17200914.

- ↑ Vieweg V, Pandurangi A, Levenson J, Silverman J (1994). "The consulting psychiatrist and the polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome in schizophrenia". Int J Psychiatry Med 24 (4): 275–303. PMID 7737786.

- ↑ Kishi Y, Kurosawa H, Endo S (1998). "Is propranolol effective in primary polydipsia?". Int J Psychiatry Med 28 (3): 315–25. PMID 9844835.

- ↑ Kramer MS, Gorkin R, DiJohnson C (1989). "Treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with propranolol: a controlled replication study". Hillside J Clin Psychiatry 11 (2): 107–19. PMID 2577308.

- ↑ Thibaut F, Colonna L (1993). "[Anti-aggressive effect of beta-blockers]" (in French). Encephale 19 (3): 263–7. PMID 7903928.

- ↑ Sheetal Ladva (2006-06-28). "NICE and BHS launch updated hypertension guideline". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Retrieved on 2006-09-30.

- ↑ "Doctors test a drug to ease traumatic memories - Mental Health - MSNBC.com". Retrieved on 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Brunet A, Orr SP, Tremblay J, Robertson K, Nader K, Pitman RK (2007). Effect of post-retrieval propranolol on psychophysiologic responding during subsequent script-driven traumatic imagery in post-traumatic stress disorder. pp. 503. doi:. PMID 17588604.

- ↑ "Effect of post-retrieval propranolol on psychophysiologic responding during subsequent script-driven traumatic imagery in post-traumatic stress disorder".

- ↑ *Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary, 47th edition. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2004.

- ↑ Ohnishi S, Sadanaga K, Katsuoka M, Weidanz W (1990). "Effects of membrane acting-drugs on plasmodium species and sickle cell erythrocytes". Mol Cell Biochem 91 (1-2): 159–65. doi:. PMID 2695829.

- ↑ Singh N, Puri S (2000). "Interaction between chloroquine and diverse pharmacological agents in chloroquine resistant Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis". Acta Trop 77 (2): 185–93. doi:. PMID 11080509.

- ↑ Murphy S, Harrison T, Hamm H, Lomasney J, Mohandas N, Haldar K (December 2006). "Erythrocyte G protein as a novel target for malarial chemotherapy". PLoS Med 3 (12): e528. doi:. PMID 17194200.

External links

- Historical Remarks about Propranolol and its inventor

- Scientific American Interview with James McGaugh

- CBS NEWS 60 Minutes: A Pill To Forget

- Therapeutic Forgetting: The Legal and Ethical Implications of Memory Dampening (Vanderbilt Law Review)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||