Spinal disc herniation

| Spinal disc herniation Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-9 | 722.2 |

|---|---|

| OMIM | 603932 |

| DiseasesDB | 6861 |

| MedlinePlus | 000442 |

| eMedicine | orthoped/138 radio/219 |

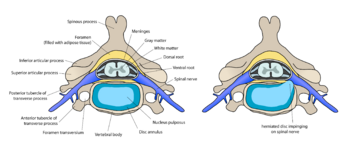

A spinal disc herniation (prolapsus disci intervertebralis), incorrectly called a "slipped disc", is a medical condition affecting the spine, in which a tear in the outer, fibrous ring (annulus fibrosus) of an intervertebral disc (discus intervertebralis) allows the soft, central portion (nucleus pulposus) to bulge out. Tears are almost always posterior-ipsilateral in nature due to the presence of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the spinal canal. This tear in the disc ring may result in the release of inflammatory chemical mediators which may directly cause severe pain, even in the absence of nerve root compression (see "chemical radiculitis" below). This is the rationale for the use of anti-inflammatory treatments for pain associated with disc herniation, protrusion, bulge, or disc tear.

It is normally a further development of a previously existing disc protrusion, a condition in which the outermost layers of the annulus fibrosus are still intact, but can bulge when the disc is under pressure.

Contents |

Terminology

Some of the terms commonly used to describe the condition include herniated disc, prolapsed disc, ruptured disc and the misleading expression "slipped disc". Other terms that are closely related include disc protrusion, bulging disc, pinched nerve, sciatica, disc disease, disc degeneration, degenerative disc disease, and black disc.[1]

The popular term "slipped disc" is quite misleading, as an intervertebral disc, being tightly sandwiched between two vertebrae to which the disc is attached, cannot actually "slip", "slide", or even get "out of place". The disc is actually grown together with the adjacent vertebrae and can be squeezed, stretched and twisted, all in small degrees. It can also be torn, ripped, herniated, and degenerated, but it cannot "slip".[2] "The term 'slipped disc' is not only wrong but also harmful as it leads to a false idea of what is happening and therefore of the likely outcome."[3][4] However, one vertebral body can slip relative to an adjacent vertebral body. This is called spondylolisthesis and can damage the disc between the two vertebrae.

The spelling "disc" is based on the Latin root discus. Most English language publications use the spelling "disc" more often than "disk". Nomina Anatomica designates the structures as "disci intervertebrales" [plural form] and Terminologia Anatomica as "discus intervertebralis/intervertebral disc", [singular form].[5]

Regional distribution

Frequency

Disc herniation can occur in any disc in the spine, but the two most common forms are the cervical disc herniation and the lumbar disc herniation. The latter is the most common, causing lower back pain (lumbago) and often leg pain as well, in which case it is commonly referred to as sciatica.

Lumbar disc herniation occurs 15 times more often than cervical (neck) disc herniation, and it is one of the most common causes of lower back pain. The cervical discs are affected 8% of the time and the upper-to-mid-back (thoracic) discs only 1 - 2% of the time.[6]

The following locations have no discs and are therefore exempt from the risk of disc herniation: the upper two cervical intervertebral spaces, the sacrum, and the coccyx.

Most disc herniations occur when a person is in their thirties or forties when the nucleus pulposus is still a gelatin-like substance. With age the nucleus pulposus changes ("dries out") and the risk of herniation is greatly reduced. After age 50 or 60, osteoarthritic degeneration or spinal stenosis are more likely causes of low back pain or leg pain.

Cervical disc herniation

Cervical disc herniations occur in the neck, most often between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebral bodies. Symptoms can affect the back of the skull, the neck, shoulder girdle, scapula,[7] shoulder, arm, and hand. The nerves of the cervical plexus and brachial plexus can be affected.[8]

Thoracic disc herniation

Thoracic discs are very stable and herniations in this region are quite rare. Herniation of the uppermost thoracic discs can mimic cervical disc herniations, while herniation of the other discs can mimic lumbar herniations.[9]

Lumbar disc herniation

Lumbar disc herniations occur in the lower back, most often between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebral bodies or between the fifth and the sacrum. Symptoms can affect the lower back, buttocks, thigh, and may radiate into the foot and/or toe. The sciatic nerve is the most commonly affected nerve, causing symptoms of sciatica. The femoral nerve can also be affected.[10] Can cause the patient to experience a numb, tingling feeling throughout one or both legs and even feet or even a burning feeling in the hips and legs.

Causes

Disc herniations can occur from general wear and tear, such as jobs that require constant sitting, but especially jobs that require lifting. Traumatic (quick) injury to lumbar discs commonly occurs from lifting while bent at the waist, rather than lifting while using the legs with a straightened back. Minor back pain and chronic back tiredness is an indicator of general wear and tear that makes one susceptible to herniation on the occurrence of a traumatic event from bending to pick up a pencil, or heavy backpack from the floor. When the spine is straight, such as standing or lying down, internal pressure is equalized on all parts of the discs. While sitting or bending to lift, internal pressure on a disc can move from 17 psi (lying down) to over 300 psi (lifting with a rounded back).

Herniation of the contents of the disc into the spinal canal often occurs when the front side (stomach side) of the disc is compressed while sitting or bending forward, and the contents (nucleus pulposus) get pressed against the tightly stretched and thinned membrane (annulus fibrosis) on the rear (back side) of the disc. The combination of membrane thinning from stretching and increased internal pressure (200 to 300 psi) results in the rupture of the confining membrane. The jelly-like contents of the disc then move into the spinal canal, pressing against the spinal nerves, thus producing intense and usually disabling pain and other symptoms.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a herniated disc can vary depending on the location of the herniation and the types of soft tissue that become involved. They can range from little or no pain if the disc is the only tissue injured, to severe and unrelenting neck or low back pain that will radiate into the regions served by affected nerve roots that are irritated or impinged by the herniated material. Other symptoms may include sensory changes such as numbness, tingling, muscular weakness, paralysis, paresthesia, and affection of reflexes. If the herniated disc is in the lumbar region the patient may also experience sciatica due to irritation of the sciatic nerve. Unlike a pulsating pain or pain that comes and goes, which can be caused by muscle spasm, pain from a herniated disc is usually continuous.

It is possible to have a herniated disc without any pain or noticeable symptoms, depending on its location. If the extruded nucleus pulposus material doesn't press on soft tissues or nerves, it may not cause any symptoms. A small-sample study examining the cervical spine in symptom-free volunteers has found focal disc protrusions in 50% of participants, which shows that a considerable part of the population can have focal herniated discs in their cervical region that do not cause noticeable symptoms.[11][12]

Typically, symptoms are experienced only on one side of the body. If the prolapse is very large and presses on the spinal cord or the cauda equina in the lumbar region, affection of both sides of the body may occur, often with serious consequences.

There is now recognition of the importance of “chemical radiculitis” in the generation of back pain.[13] A primary focus of surgery is to remove “pressure” or reduce mechanical compression on a neural element: either the spinal cord, or a nerve root. But it is increasingly recognized that back pain, rather than being solely due to compression, may also be due to chemical inflammation.[14][15][16][13] There is evidence that points to a specific inflammatory mediator of this pain.[17][18] This inflammatory molecule, called tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF), is released not only by the herniated disc, but also in cases of disc tear (annular tear), by facet joints, and in spinal stenosis.[13][19][20][21] In addition to causing pain and inflammation, TNF may also contribute to disc degeneration.[22]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by a practitioner based on the history, symptoms, and physical examination. At some point in the evaluation, tests may be performed to confirm or rule out other causes of symptoms such as spondylolisthesis, degeneration, tumors, metastases and space-occupying lesions as well as evaluate the efficacy of potential treatment options.

Physical examination

Straight leg raise

The Straight leg raise may be positive; however, this finding has low specificity. A variation is to lift the leg while the patient is sitting.[23] However, this reduces the sensitivity of the test.[24]

Imaging

- X-ray: Although traditional plain X-rays are limited in their ability to image soft tissues such as discs, muscles, and nerves, they are still used to confirm or exclude other possibilities such as tumors, infections, fractures, etc.. In spite of these limitations, X-ray can still play a relatively inexpensive role in confirming the suspicion of the presence of a herniated disc. If a suspicion is thus strengthened, other methods may be used to provide final confirmation.

- Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan): A diagnostic image created after a computer reads x-rays. It can show the shape and size of the spinal canal, its contents, and the structures around it, including soft tissues.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A diagnostic test that produces three-dimensional images of body structures using powerful magnets and computer technology. It can show the spinal cord, nerve roots, and surrounding areas, as well as enlargement, degeneration, and tumors. It shows soft tissues even better than CAT scans.

- Myelogram: An x-ray of the spinal canal following injection of a contrast material into the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid spaces. By revealing displacement of the contrast material, it can show the presence of structures that can cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerves, such as herniated discs, tumors, or bone spurs. Because it involves the injection of foreign substances, MRI scans are now preferred in most patients. Myelograms still provide excellent outlines of space-occupying lesions, especially when combined with CT scanning (CT myelography).

- Electromyogram and Nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS): These tests measure the electrical impulse along nerve roots, peripheral nerves, and muscle tissue. This will indicate whether there is ongoing nerve damage, if the nerves are in a state of healing from a past injury, or whether there is another site of nerve compression.

Treatment

The majority of herniated discs will heal themselves in about six weeks and do not require surgery. One study found that "After 12 weeks, 73% of patients showed reasonable to major improvement without surgery." [25]

If pain due to disc herniation, protrusion, bulge, or disc tear is due to chemical radiculitis pain, then prior to surgery it may make sense to try an anti-inflammatory approach. Often this is first attempted with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, but the long-term use of NSAIDS for patients with persistent back pain is complicated by their possible cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicity; and NSAIDs have limited value to intervene in tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF)-mediated processes.[26] An alternative often employed is the injection of cortisone into the spine adjacent to the suspected pain generator, a technique known as “epidural steroid injection”.[27] Although this technique began more than a decade ago for pain due to disc herniation, the efficacy of epidural steroid injections is now generally thought to be limited to short term pain relief in selected patients only. [28] In addition, epidural steroid injections, in certain settings, may result in serious complications. [29] Fortunately there are now emerging new methods that directly target TNF. [30] These TNF-targeted methods represent a highly promising new approach for patients with chronic severe spinal pain, such as those with failed back surgery syndrome. [30] Ancillary approaches, such as rehabilitation, physical therapy, anti-depressants, and, in particular, graduated exercise programs, may all be useful adjuncts to anti-inflammatory approaches. [26]

Conservative treatment

Pain medications are often prescribed to alleviate the acute pain and allow the patient to begin exercising and stretching.

There are a variety of non-surgical care alternatives to treat the pain, including:

- Bed rest and lumbo-sacral support belt.

- Chiropractic manipulations. Patients with a herniated disc may be at increased risks of worsening disc herniation or cauda equina syndrome due to manipulation.[31] An estimate of the risk of spinal manipulation causing a clinically worsened disc herniation or cauda equina syndrome in a patient presenting with lumbar disc herniation is calculated from published data to be less than 1 in 3.7 million.

- Physical therapy

- Yoga therapy (specialized back care through modified Yoga poses)

- Massage therapy

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Oral steroids (e.g. prednisone or methyprednisolone)

- Epidural (cortisone) injection

- Intravenous sedation, analgesia-assisted traction therapy (IVSAAT)

- Weight control [32]

- Spinal decompression

Surgery

Surgery is indicated if a patient has a significant neurological deficit, or if they fail non-surgical therapy.[33] The presence of cauda equina syndrome (in which there is incontinence, weakness and genital numbness) is considered a medical emergency requiring immediate attention and possibly surgical decompression.

Regarding the role of surgery for failed medical therapy in patients without a significant neurological deficit, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that "limited evidence is now available to support some aspects of surgical practice". More recent randomized controlled trials refine indications for surgery

- The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT)

- Patients studied. "intervertebral disk herniation and persistent symptoms despite some nonoperative treatment for at least 6 weeks...radicular pain (below the knee for lower lumbar herniations, into the anterior thigh for upper lumbar herniations) and evidence of nerve-root irritation with a positive nerve-root tension sign (straight leg raise–positive between 30° and 70° or positive femoral tension sign) or a corresponding neurologic deficit (asymmetrical depressed reflex, decreased sensation in a dermatomal distribution, or weakness in a myotomal distribution)

- Conclusions. "Patients in both the surgery and the nonoperative treatment groups improved substantially over a 2-year period. Because of the large numbers of patients who crossed over in both directions, conclusions about the superiority or equivalence of the treatments are not warranted based on the intent-to-treat analysis"[34][35]

- The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group[36]

- Patients studied. "had a radiologically confirmed disk herniation...incapacitating lumbosacral radicular syndrome that had lasted for 6 to 12 weeks...Patients presenting with cauda equina syndrome, muscle paralysis, or insufficient strength to move against gravity were excluded."

- Conclusions. "The 1-year outcomes were similar for patients assigned to early surgery and those assigned to conservative treatment with eventual surgery if needed, but the rates of pain relief and of perceived recovery were faster for those assigned to early surgery. "

Surgical options include:

- Microdiscectomy[37]

- IDET (a minimally invasive surgery for disc pain)

- Laminectomy - to relieve spinal stenosis or nerve compression

- Hemilaminectomy - to relieve spinal stenosis or nerve compression

- Lumbar fusion (lumbar fusion is only indicated for recurrent lumbar disc herniations, not primary herniations)

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (for cervical disc herniation)

- Disc arthroplasty (experimental for cases of cervical disc herniation)

- Dynamic stabilization

- Artificial disc replacement, a relatively new form of surgery in the U.S. but has been in use in Europe for decades, primarily used to treat low back pain from a degenerated disc.

Surgical goals include relief of nerve compression, allowing the nerve to recover, as well as the relief of associated back pain and restoration of normal function.

Classical surgery for lumbar disc herniation is carried out by using a vertical median incision over the level which has an herniation. The dorsolumbar fascia is incised about 0.5 cm laterally on the affected side. The paravertebral muscles are dissected free from underlying bony structures, namely the spinous process and laminae, and retracted laterally. The level of disc herniation is identified using C-arm fluoroscopy or palpating the sacrum. The lamina is then fenestrated with bone rongeurs after which the exposed ligamentum flavum (the yellow ligament) is excised. The epidural soft tissue and venous plexus is gently explored to find the nerve root exiting from the associated neural foramina. The herniated disc is usually found beneath the nerve root. The nerve root is protected using root retractors. The posterior longitudinal ligament is incised with a fine blade and herniated disc material and degenerated nucleus pulposus are evacuated using different kinds of disc forcepses. Meticulous control of haemostasis is employed and irrigation with warm saline is essential. The muscle layers and the fascia is repaired, generally, without using a drain. The skin wound is closed.

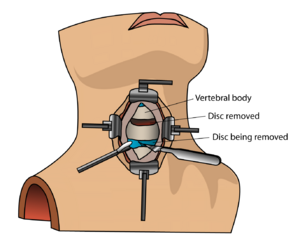

Cervical intervertebral disc herniations are operated using a horizontal paramedian anterior neck incision parallel to skin folds, a surgical procedure called Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. After dissecting the neck structures (which are vital organs, such as trachea, esophagus, carotid arteries etc.), the front of the vertebral column is reached and exposure is maintained by automatic retractors. The dissection is blunt and is carried out through natural anatomic planes, thus causing minimal trauma to tissues here. The level is again verified using the C-arm. The disc is evacuated using curettes and high speed drills. The surgeon may place an intervertebral support, such as autologous bone or allogrefts, or metallic elements for fusion. The incision is then closed layer by layer. Another approach for cervical herniations is the posterior approach, which is basically identical to surgical treatment for lumbar disc surgery. The decision of which route to employ is arrived after complete workup of a patient.

Emerging Treatment Options

The identification of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) as a central cause of inflammatory spinal pain now suggests the possibility of an entirely new approach to selected patients with severe pain due to disc herniation, protrusion, bulge, or disc tear. Specific and potent inhibitors of TNF became available in the U.S. in 1998, and were demonstrated to be potentially effective for treating sciatica in experimental models beginning in 2001. [38][39][40] Targeted anatomic administration of one of these anti-TNF agents, etanercept, a patented treatment method,[41] has been suggested in published pilot studies to be effective for treating selected patients with severe pain due to disc herniation, protrusion, bulge, or disc tear. [30][42] The scientific basis for pain relief in these patients is supported by the most current review articles. [43][44] In the future new imaging methods may allow non-invasive identification of sites of neuronal inflammation, thereby enabling more accurate localization of the "pain generators" responsible for symptom production.

Investigational treatments

Future treatments may include stem cell therapy. Doctors Victor Y. L. Leung, Danny Chan and Kenneth M. C. Cheung have reported in the European Spine Journal that "substantial progress has been made in the field of stem cell regeneration of the intervertebral disc. Autogenic mesenchymal stem cells in animal models can arrest intervertebral disc degeneration or even partially regenerate it and the effect is suggested to be dependent on the severity of the degeneration."[45] Successful disc regeneration in animal models, until recently, did not translate into human models. This is due to a number of factors, but primarily because the larger human disc has a greater area of nutrient poor/ avascular tissue than the smaller animal disc. Recent successful autologous mesenchymal stem cell mediated regeneration of human discs [1], however show great promise as an alternative to traditional surgery

See also

- Back pain

- Degenerative disc disease

- Low back pain

- Sciatica

- Vertebral column

References

- ↑ [considered spam "What is a herniated disc, bulging disc, ..."]

- ↑ Slipped discs: "they do not actually 'slip'..."

- ↑ Prolapsed disc

- ↑ Ehealthmd.com FAQ: "...the entire disc does not 'slip' out of place."

- ↑ Terminology

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Herniated nucleus pulposus Frequency

- ↑ "Neck and Shoulder Blade Pain".

- ↑ Cervical herniation at eMedicine

- ↑ Thoracic herniation at eMedicine

- ↑ Lumbar herniation at eMedicine

- ↑ Robert E Windsor (2006). "Frequency of asymptomatic cervical disc protrusions". Cervical Disc Injuries.. eMedicine. Retrieved on 2008-02-27.

- ↑ Ernst CW, Stadnik TW, Peeters E, Breucq C, Osteaux MJ (Sep 2005). "Prevalence of annular tears and disc herniations on MR images of the cervical spine in symptom free volunteers". Eur J Radiol 55 (3): 409–14. doi:. PMID 16129249.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Peng B, Wu W, Li Z, Guo J, Wang X (Jan 2007). "Chemical radiculitis". Pain 127 (1-2): 11–6. doi:. PMID 16963186.

- ↑ Marshall LL, Trethewie ER (Aug 1973). "Chemical irritation of nerve-root in disc prolapse". Lancet 2 (7824): 320. doi:. PMID 4124797.

- ↑ McCarron RF, Wimpee MW, Hudkins PG, Laros GS (Oct 1987). "The inflammatory effect of nucleus pulposus. A possible element in the pathogenesis of low-back pain". Spine 12 (8): 760–4. doi:. PMID 2961088.

- ↑ Takahashi H, Suguro T, Okazima Y, Motegi M, Okada Y, Kakiuchi T (Jan 1996). "Inflammatory cytokines in the herniated disc of the lumbar spine". Spine 21 (2): 218–24. doi:. PMID 8720407. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=21&issue=2&spage=218.

- ↑ Igarashi T, Kikuchi S, Shubayev V, Myers RR (Dec 2000). "2000 Volvo Award winner in basic science studies: Exogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha mimics nucleus pulposus-induced neuropathology. Molecular, histologic, and behavioral comparisons in rats". Spine 25 (23): 2975–80. doi:. PMID 11145807. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=25&issue=23&spage=2975.

- ↑ Sommer C, Schäfers M (2004). "Mechanisms of neuropathic pain: the role of cytokines". Drug Discovery Today: Disease Mechanisms 1 (4): 441–8. doi:.

- ↑ Igarashi A, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Olmarker K (Oct 2004). "Inflammatory cytokines released from the facet joint tissue in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders". Spine 29 (19): 2091–5. doi:. PMID 15454697. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=29&issue=19&spage=2091.

- ↑ Sakuma Y, Ohtori S, Miyagi M, et al (Aug 2007). "Up-regulation of p55 TNF alpha-receptor in dorsal root ganglia neurons following lumbar facet joint injury in rats". Eur Spine J 16 (8): 1273–8. doi:. PMID 17468886.

- ↑ Sekiguchi M, Kikuchi S, Myers RR (May 2004). "Experimental spinal stenosis: relationship between degree of cauda equina compression, neuropathology, and pain". Spine 29 (10): 1105–11. doi:. PMID 15131438. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=29&issue=10&spage=1105.

- ↑ Séguin CA, Pilliar RM, Roughley PJ, Kandel RA (Sep 2005). "Tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulates matrix production and catabolism in nucleus pulposus tissue". Spine 30 (17): 1940–8. doi:. PMID 16135983. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=30&issue=17&spage=1940.

- ↑ Waddell G, McCulloch JA, Kummel E, Venner RM (1980). "Nonorganic physical signs in low-back pain". Spine 5 (2): 117–25. doi:. PMID 6446157.

- ↑ Rabin A, Gerszten PC, Karausky P, Bunker CH, Potter DM, Welch WC (2007). "The sensitivity of the seated straight-leg raise test compared with the supine straight-leg raise test in patients presenting with magnetic resonance imaging evidence of lumbar nerve root compression". Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 88 (7): 840–3. doi:. PMID 17601462.

- ↑ Vroomen PC, de Krom MC, Knottnerus JA (Feb 2002). "Predicting the outcome of sciatica at short-term follow-up". Br J Gen Pract 52 (475): 119–23. PMID 11887877. PMC: 1314232. http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=0960-1643&volume=52&issue=475&spage=119&aulast=Vroomen.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Carragee EJ (May 2005). "Clinical practice. Persistent low back pain". N Engl J Med. 352 (18): 1891–8. doi:. PMID 15872204.

- ↑ Fredman B, Nun MB, Zohar E, et al (Feb 1999). "Epidural steroids for treating "failed back surgery syndrome": is fluoroscopy really necessary?". Anesth Analg. 88 (2): 367–72. doi:. PMID 9972758. http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9972758.

- ↑ Landau WM, Nelson DA, Armon C, Argoff CE, Samuels J, Backonja MM (Aug 2007). "Assessment: use of epidural steroid injections to treat radicular lumbosacral pain: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology 69 (6): 614; author reply 614–5. doi:. PMID 17679685.

- ↑ Abbasi A, Malhotra G, Malanga G, Elovic EP, Kahn S (Sep 2007). "Complications of interlaminar cervical epidural steroid injections: a review of the literature". Spine 32 (19): 2144–51. doi:. PMID 17762818.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Tobinick EL, Britschgi-Davoodifar S (Mar 2003). "Perispinal TNF-alpha inhibition for discogenic pain". Swiss Med Wkly 133 (11-12): 170–7. doi:2003/11/smw-10163 (inactive 2008-11-18). PMID 12715286.

- ↑ Stevinson C, Ernst E (2002). "Risks associated with spinal manipulation". Am J Med 112 (7): 566–71. doi:. PMID 12015249.

- ↑ "Rush University Medical Center". Retrieved on 2008-03-012.

- ↑ Stern, Scott D.; Adam S. Cifu, Diane Altkorn (2006). "Back Pain". in Janet Foltin, Harriet Lebowitz, Karen Davis. Symptom to Diagnosis: An Evidence-Based Guide. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill. pp. 67–81. ISBN 0071463895.

- ↑ Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al (2006). "Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial". JAMA 296 (20): 2441–50. doi:. PMID 17119140.

- ↑ Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al (2006). "Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort". JAMA 296 (20): 2451–9. doi:. PMID 17119141.

- ↑ Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, et al (2007). "Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica". N Engl J Med. 356 (22): 2245–56. doi:. PMID 17538084. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/short/356/22/2245.

- ↑ [considered spam Microdiscectomy]

- ↑ Sommer C, Schäfers M, Marziniak M, Toyka KV (Jun 2001). "Etanercept reduces hyperalgesia in experimental painful neuropathy". J Peripher Nerv Syst. 6 (2): 67–72. doi:. PMID 11446385. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1085-9489&date=2001&volume=6&issue=2&spage=67.

- ↑ Olmarker K, Rydevik B (Apr 2001). "Selective inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha prevents nucleus pulposus-induced thrombus formation, intraneural edema, and reduction of nerve conduction velocity: possible implications for future pharmacologic treatment strategies of sciatica". Spine 26 (8): 863–9. doi:. PMID 11317106. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=26&issue=8&spage=863.

- ↑ Murata Y, Onda A, Rydevik B, Takahashi K, Olmarker K (Nov 2004). "Selective inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha prevents nucleus pulposus-induced histologic changes in the dorsal root ganglion". Spine 29 (22): 2477–84. doi:. PMID 15543058. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-2436&volume=29&issue=22&spage=2477.

- ↑ US patent 6537549 and others

- ↑ Tobinick E, Davoodifar S (Jul 2004). "Efficacy of etanercept delivered by perispinal administration for chronic back and/or neck disc-related pain: a study of clinical observations in 143 patients". Curr Med Res Opin 20 (7): 1075–85. doi:. PMID 15265252.

- ↑ Myers RR, Campana WM, Shubayev VI (Jan 2006). "The role of neuroinflammation in neuropathic pain: mechanisms and therapeutic targets". Drug Discov Today 11 (1-2): 8–20. doi:. PMID 16478686.

- ↑ Üçeyler N, Sommer C (2007). "Cytokine-induced Pain: Basic Science and Clinical Implications". Reviews in Analgesia 9 (2): 87–103. doi:. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cog/ria/2007/00000009/00000002/art00003.

- ↑ Leung VY, Chan D, Cheung KM (Aug 2006). "Regeneration of intervertebral disc by mesenchymal stem cells: potentials, limitations, and future direction". Eur Spine J 15 Suppl 3: S406–13. doi:. PMID 16845553.