Private equity

| Financial market participants |

|

|

|

|

Collective investment schemes |

|

|

Finance series |

|

In finance, private equity is an asset class consisting of equity securities in operating companies that are not publicly traded on a stock exchange.

There is a wide array of types and styles of private equity and the term private equity has different connotations in different countries.[1]

Contents |

Types of private equity

Private equity investments can be divided into the following categories:

- Leveraged buyout, LBO or simply Buyout: refers to a strategy of making equity investments as part of a transaction in which a company, business unit or business assets is acquired from the current shareholders typically with the use of financial leverage. The companies involved in these transactions are typically more mature and generate operating cash flows.

- Venture capital: a broad subcategory of private equity that refers to equity investments made, typically in less mature companies, for the launch, early development, or expansion of a business. Venture capital is often sub-divided by the stage of development of the company ranging from early stage capital used for the launch of start-up companies to late stage and growth capital that is often used to fund expansion of existing business that are generating revenue but may not yet be profitable or generating cash flow to fund future growth.[2]

- Growth capital: refers to equity investments, most often minority investments, in more mature companies that are looking for capital to expand or restructure operations, enter new markets or finance a major acquisition without a change of control of the business.

Other strategies

Other strategies that can be considered private equity or a close adjacent market include:

- Distressed or Special situations: can refer to investments in equity or debt securities of a distressed company, or a company where value can be unlocked as a result of a one-time opportunity (e.g., a change in government regulations or market dislocation). These categories can refer to a number of strategies, some of which straddle the definition of private equity.

- Mezzanine capital: refers to subordinated debt or preferred equity securities that often represent the most junior portion of a company's capital structure that is senior to the company's common equity.

- Real Estate: in the context of private equity this will typically refer to the riskier end of the investment spectrum including "value added" and opportunity funds where the investments often more closely resemble leveraged buyouts than traditional real estate investments. Certain investors in private equity consider real estate to be a separate asset class.

- Secondary investments: refer to investments made in existing private equity assets including private equity fund interests or portfolios of direct investments in privately held companies through the purchase of these investments from existing institutional investors. Often these investments are structured similar to a fund of funds.[3]

- Infrastructure: investments in various public works (e.g., bridges, tunnels, toll roads, airports, public transportation and other public works) that are made typically as part of a privatization initiative on the part of a government entity.[4][5][6]

- Energy and Power: investments in a wide variety of companies (rather than assets) engaged in the production and sale of energy, including fuel extraction, manufacturing, refining and distribution (Energy) or companies engaged in the production or transmission of electrical power (Power).

- Merchant banking: negotiated private equity investment by financial institutions in the unregistered securities of either privately or publicly held companies.[7]

History and further development

Early history and the development of venture capital

The seeds of the private equity industry were planted in 1946 with the founding of two venture capital firms: American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) and J.H. Whitney & Company.[8] Before World War II, venture capital investments (originally known as "development capital") were primarily the domain of wealthy individuals and families. ARDC was founded by Georges Doriot, the "father of venture capitalism"[9] and founder of INSEAD, with capital raised from institutional investors, to encourage private sector investments in businesses run by soldiers who were returning from World War II. ARDC is credited with the first major venture capital success story when its 1957 investment of $70,000 in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) would be valued at over $355 million after the company's initial public offering in 1968 (representing a return of over 500 times on its investment and an annualized rate of return of 101%).[10] It is commonly noted that the first venture-backed startup is Fairchild Semiconductor (which produced the first commercially practicable integrated circuit), funded in 1959 by what would later become Venrock Associates.[11]

Origins of the leveraged buyout

The first leveraged buyout may have been the purchase by McLean Industries, Inc. of Pan-Atlantic Steamship Company in January 1955 and Waterman Steamship Corporation in May 1955[12] Under the terms of that transaction, McLean borrowed $42 million and raised an additional $7 million through an issue of preferred stock. When the deal closed, $20 million of Waterman cash and assets were used to retire $20 million of the loan debt.[13] Similar to the approach employed in the McLean transaction, the use of publicly traded holding companies as investment vehicles to acquire portfolios of investments in corporate assets was a relatively new trend in the 1960s popularized by the likes of Warren Buffett (Berkshire Hathaway) and Victor Posner (DWG Corporation) and later adopted by Nelson Peltz (Triarc), Saul Steinberg (Reliance Insurance) and Gerry Schwartz (Onex Corporation). These investment vehicles would utilize a number of the same tactics and target the same type of companies as more traditional leveraged buyouts and in many ways could be considered a forerunner of the later private equity firms. In fact it is Posner who is often credited with coining the term "leveraged buyout" or "LBO"[14]

The leveraged buyout boom of the 1980s was conceived by a number of corporate financiers, most notably Jerome Kohlberg, Jr. and later his protégé Henry Kravis. Working for Bear Stearns at the time, Kohlberg and Kravis along with Kravis' cousin George Roberts began a series of what they described as "bootstrap" investments. Many of these companies lacked a viable or attractive exit for their founders as they were too small to be taken public and the founders were reluctant to sell out to competitors and so a sale to a financial buyer could prove attractive. Their acquisition of Orkin Exterminating Company in 1964 is among the first significant leveraged buyout transactions.[15]. In the following years the three Bear Stearns bankers would complete a series of buyouts including Stern Metals (1965), Incom (a division of Rockwood International, 1971), Cobblers Industries (1971), and Boren Clay (1973) as well as Thompson Wire, Eagle Motors and Barrows through their investment in Stern Metals. [16] By 1976, tensions had built up between Bear Stearns and Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts leading to their departure and the formation of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts in that year.

Private equity in the 1980s

In January 1982, former US Secretary of the Treasury William Simon and a group of investors acquired Gibson Greetings, a producer of greeting cards, for $80 million, of which only $1 million was rumored to have been contributed by the investors. By mid-1983, just sixteen months after the original deal, Gibson completed a $290 million IPO and Simon made approximately $66 million.[17] The success of the Gibson Greetings investment attracted the attention of the wider media to the nascent boom in leveraged buyouts. Between 1979 and 1989, it was estimated that there were over 2,000 leveraged buyouts valued in excess of $250 million[18]

During the 1980s, constituencies within acquired companies and the media ascribed the "corporate raid" label to many private equity investments, particularly those that featured a hostile takeover of the company, perceived asset stripping, major layoffs or other significant corporate restructuring activities. Among the most notable investors to be labeled corporate raiders in the 1980s included Carl Icahn, Victor Posner, Nelson Peltz, Robert M. Bass, T. Boone Pickens, Harold Clark Simmons, Kirk Kerkorian, Sir James Goldsmith, Saul Steinberg and Asher Edelman. Carl Icahn developed a reputation as a ruthless corporate raider after his hostile takeover of TWA in 1985.[19][20] Many of the corporate raiders were onetime clients of Michael Milken, whose investment banking firm, Drexel Burnham Lambert helped raise blind pools of capital with which corporate raiders could make a legitimate attempt to takeover a company and provided high-yield debt financing of the buyouts.

One of the final major buyouts of the 1980s proved to be its most ambitious and marked both a high water mark and a sign of the beginning of the end of the boom that had begun nearly a decade earlier. In 1989, KKR closed in on a $31.1 billion dollar takeover of RJR Nabisco. It was, at that time and for over 17 years, the largest leverage buyout in history. The event was chronicled in the book (and later the movie), Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco. KKR would eventually prevail in acquiring RJR Nabisco at $109 per share marking a dramatic increase from the original announcement that Shearson Lehman Hutton would take RJR Nabisco private at $75 per share. A fierce series of negotiations and horse-trading ensued which pitted KKR against Shearson Lehman Hutton and later Forstmann Little & Co. Many of the major banking players of the day, including Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Salomon Brothers, and Merrill Lynch were actively involved in advising and financing the parties. After Shearson Lehman's original bid, KKR quickly introduced a tender offer to obtain RJR Nabisco for $90 per share—a price that enabled it to proceed without the approval of RJR Nabisco's management. RJR's management team, working with Shearson Lehman and Salomon Brothers, submitted a bid of $112, a figure they felt certain would enable them to outflank any response by Kravis's team. KKR's final bid of $109, while a lower dollar figure, was ultimately accepted by the board of directors of RJR Nabisco.[21] At $31.1 billion of transaction value, RJR Nabisco was by far the largest leveraged buyouts in history. In 2006 and 2007, a number of leveraged buyout transactions were completed that for the first time surpassed the RJR Nabisco leveraged buyout in terms of nominal purchase price. However, adjusted for inflation, none of the leveraged buyouts of the 2006 – 2007 period would surpass RJR Nabisco.

By the end of the 1980s the excesses of the buyout market were beginning to show, with the bankruptcy of several large buyouts including Robert Campeau's 1988 buyout of Federated Department Stores, the 1986 buyout of the Revco drug stores, Walter Industries, FEB Trucking and Eaton Leonard. Additionally, the RJR Nabisco deal was showing signs of strain, leading to a recapitalization in 1990 that involved the contribution of $1.7 billion of new equity from KKR.[22]

Drexel Burnham Lambert was the investment bank most responsible for the boom in private equity during the 1980s due to its leadership in the issuance of high-yield debt.

Drexel reached an agreement with the government in which it pleaded nolo contendere (no contest) to six felonies – three counts of stock parking and three counts of stock manipulation.[23] It also agreed to pay a fine of $650 million – at the time, the largest fine ever levied under securities laws. Milken left the firm after his own indictment in March 1989.[24][25] On February 13, 1990 after being advised by Secretary of the Treasury Nicholas F. Brady, the SEC, the NYSE and the Federal Reserve, Drexel Burnham Lambert officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.[24]

Age of the mega-buyout 2005-2007

The combination of decreasing interest rates, loosening lending standards and regulatory changes for publicly traded companies (specifically the Sarbanes-Oxley Act) would set the stage for the largest boom private equity had seen. Marked by the buyout of Dex Media in 2002, large multi-billion dollar U.S. buyouts could once again obtain significant high yield debt financing and larger transactions could be completed. By 2004 and 2005, major buyouts were once again becoming common, including the acquisitions of Toys "R" Us[26], The Hertz Corporation [27][28], Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer[29] and SunGard[30] in 2005.

As 2005 ended and 2006 began, new "largest buyout" records were set and surpassed several times with nine of the top ten buyouts at the end of 2007 having been announced in an 18-month window from the beginning of 2006 through the middle of 2007. In 2006, private equity firms bought 654 U.S. companies for $375 billion, representing 18 times the level of transactions closed in 2003.[31] Additionally, U.S. based private equity firms raised $215.4 billion in investor commitments to 322 funds, surpassing the previous record set in 2000 by 22% and 33% higher than the 2005 fundraising total[32] The following year, despite the onset of turmoil in the credit markets in the summer, saw yet another record year of fundraising with $302 billion of investor commitments to 415 funds[33] Among the mega-buyouts completed during the 2006 to 2007 boom were: Equity Office Properties, HCA[34], Alliance Boots[35] and TXU[36].

In July 2007, turmoil that had been affecting the mortgage markets, spilled over into the leveraged finance and high-yield debt markets.[37][38] The markets had been highly robust during the first six months of 2007, with highly issuer friendly developments including PIK and PIK Toggle (interest is "Payable In Kind") and covenant light debt widely available to finance large leveraged buyouts. July and August saw a notable slowdown in issuance levels in the high yield and leveraged loan markets with few issuers accessing the market. Uncertain market conditions led to a significant widening of yield spreads, which coupled with the typical summer slowdown led many companies and investment banks to put their plans to issue debt on hold until the autumn. However, the expected rebound in the market after Labor Day 2007 did not materialize and the lack of market confidence prevented deals from pricing. By the end of September, the full extent of the credit situation became obvious as major lenders including Citigroup and UBS AG announced major writedowns due to credit losses. The leveraged finance markets came to a near standstill.[39] As 2007 ended and 2008 began, it was clear that lending standards had tightened and the era of "mega-buyouts" had come to an end. Nevertheless, private equity continues to be a large and active asset class and the private equity firms, with hundreds of billions of dollars of committed capital from investors are looking to deploy capital in new and different transactions.

Investments in private equity

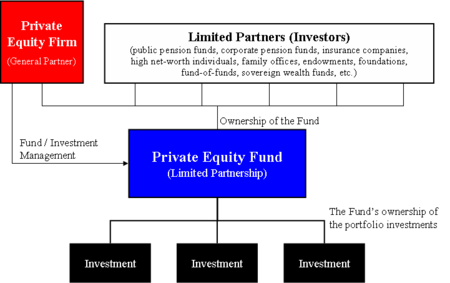

Institutional investors provide private equity capital in the hopes of achieving risk adjusted returns that exceed those possible in the public equity markets and will typically include private equity as part of a broad asset allocation that includes traditional assets (e.g., public equity and bonds). Most institutional investors, do not invest directly in privately held companies, lacking the expertise and resources necessary to structure and monitor the investment. Instead, institutional investors will invest indirectly through a private equity fund. Certain institutional investors have the scale necessary to develop a diversified portfolio of private equity funds themselves, while others will invest through a fund of funds to allow a portfolio more diversified than one a single investor could construct.

Private equity firms generally receive a return on their investments through one of the following avenues:

- an Initial Public Offering (IPO) - shares of the company are offered to the public, typically providing an partial immediate realization to the financial sponsor as well as a public market into which it can later sell additional shares;

- a merger or acquisition - the company is sold for either cash or shares in another company;

- a Recapitalization - cash is distributed to the shareholders (in this case the financial sponsor) and its private equity funds either from cash flow generated by the company or through raising debt or other securities to fund the distribution.

Investment features and considerations

Considerations for investing in private equity funds relative to other forms of investment include:

- Substantial entry requirements. With most private equity funds requiring significant initial commitment(usually upwards of $1,000,000) which can be drawn at the manager's discretion over the first few years of the fund.

- Limited liquidity. Investments in limited partnership interests (which is the dominant legal form of private equity investments) are referred to as "illiquid" investments which should earn a premium over traditional securities, such as stocks and bonds. Once invested, it is very difficult to achieve liquidity before the manager realizes the investments in the portfolio as an investor's capital is locked-up in long-term investments which can last for as long as twelve years. Distributions are made only as investments are converted to cash; limited partners typically have no right to demand that sales be made.

- Investment Control. Nearly all investors in private equity are passive and rely on the manager to make investments and generate liquidity from those investments. Typically, governance rights for limited partners in private equity funds are minimal.

- Unfunded Commitments. An investor's commitment to a private equity fund is drawn over time. If a private equity firm can't find suitable investment opportunities, it will not draw on an investor's commitment and an investor may potentially invest less than expected or committed.

- Investment Risks. Given the risks associated with private equity investments, an investor can lose all of its investment. The risk of loss of capital is typically higher in venture capital funds, which invest in companies during the earliest phases of their development or in companies with high amounts of financial leverage. By their nature, investments in privately held companies tend to be riskier than investments in publicly traded companies.

- High returns. Consistent with the risks outlined above, private equity can provide high returns, with the best private equity managers significantly outperforming the public markets.[40]

For the above mentioned reasons, private equity fund investment is for those who can afford to have capital locked in for long periods of time and who are able to risk losing significant amounts of money. These disadvantages are offset by the potential benefits of annual returns which range up to 30% for successful funds.

Liquidity in the private equity market

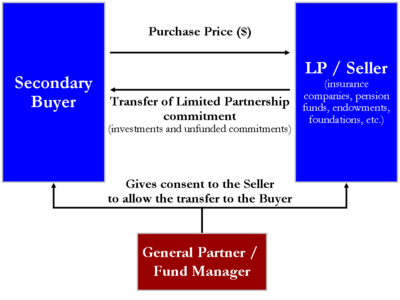

The private equity secondary market (also often called private equity secondaries) refers to the buying and selling of pre-existing investor commitments to private equity and other alternative investment funds. Sellers of private equity investments sell not only the investments in the fund but also their remaining unfunded commitments to the funds. By its nature, the private equity asset class is illiquid, intended to be a long-term investment for buy-and-hold investors. For the vast majority of private equity investments, there is no listed public market; however, there is a robust and maturing secondary market available for sellers of private equity assets.

Increasingly, secondaries are considered a distinct asset class with a cash flow profile that is not correlated with other private equity investments. As a result, investors are allocating capital to secondary investments to diversify their private equity programs. Driven by strong demand for private equity exposure, a significant amount of capital has been committed to secondary investments from investors looking to increase and diversify their private equity exposure.

Investors seeking access to private equity have been restricted to investments with structural impediments such as long lock-up periods, lack of transparency, unlimited leverage, concentrated holdings of illiquid securities and high investment minimums.

Secondary transactions can be generally split into two basic categories:

- Sale of Limited Partnership Interests - The most common secondary transaction, this category includes the sale of an investor's interest in a private equity fund or portfolio of interests in various funds through the transfer of the investor's limited partnership interest in the fund(s). Nearly all types of private equity funds (e.g., including buyout, growth equity, venture capital, mezzanine, distressed and real estate) can be sold in the secondary market. The transfer of the limited partnership interest typically will allow the investor to receive some liquidity for the funded investments as well as a release from any remaining unfunded obligations to the fund.

- Sale of Direct Interests – Secondary Directs or Synthetic secondaries, this category refers to the sale of portfolios of direct investments in operating companies, rather than limited partnership interests in investment funds. These portfolios historically have originated from either corporate development programs or large financial institutions.

Private equity firms

According to an updated 2008 ranking created by industry magazine Private Equity International[41] (published by PEI Media called the PEI 50), the largest private equity firm in the world today is The Carlyle Group, based on the amount of private equity direct-investment capital raised over a five-year window. As ranked in this article, the 10 largest private equity firms in the world are:

- The Carlyle Group

- Goldman Sachs Principal Investment Area

- TPG

- Kohlberg Kravis Roberts

- CVC Capital Partners

- Apollo Management

- Bain Capital

- Permira

- Apax Partners

- The Blackstone Group

Because private equity firms are continuously in the process of raising, investing and distributing their private equity funds, capital raised can often be the easiest to measure. Other metrics can include the total value of companies purchased by a firm or an estimate of the size of a firm's active portfolio plus capital available for new investments. As with any list that focuses on size, the list does not provide any indication as to relative investment performance of these funds or managers.

Additionally, Preqin (formerly known as Private Equity Intelligence), an independent data provider, ranks the 25 largest private equity investment managers. Among the larger firms in that ranking were AlpInvest Partners, AXA Private Equity, AIG Investments, Goldman Sachs Private Equity Group and Pantheon Ventures.

Record Private Equity Deals

The largest private equity deal of all time was that of Equity Office Properties Trust which was acquired by Blackstone in 2007 for $38.9 billion an increase of $3.1 billion because of intense bidding war[42][43]. The largest private equity deal for an Individual was the sale of London City Airport, Dermot Desmond purchased the airport for an estimated £25 million in 1995. In 2006 a consortium of AIG, GE Capital and Credit Suisse paid a reported £1.65 billion of which Dermot Desmond gained £1.2 billion[44].

Private equity funds

Private equity fundraising refers to the action of private equity firms seeking capital from investors for their funds. Typically an investor will invest in a specific fund managed by a firm, becoming a limited partner in the fund, rather than an investor in the firm itself. As a result, an investor will only benefit from investments made by a firm where the investment is made from the specific fund in which it has invested.

- Fund of funds. These are private equity funds that invest in other private equity funds in order to provide investors with a lower risk product through exposure to a large number of vehicles often of different type and regional focus. Fund of funds accounted for 14% of global commitments made to private equity funds in 2006 according to Preqin ltd (formerly known as Private Equity Intelligence)

- Individuals with substantial net worth. Substantial net worth is often required of investors by the law, since private equity funds are generally less regulated than ordinary mutual funds. For example in the US, most funds require potential investors to qualify as accredited investors, which requires $1 million of net worth, $200,000 of individual income, or $300,000 of joint income (with spouse) for two documented years and an expectation that such income level will continue.

As fundraising has grown over the past few years, so too has the number of investors in the average fund. In 2004 there were 26 investors in the average private equity fund, this figure has now grown to 42 according to Preqin ltd. (formerly known as Private Equity Intelligence).

The managers of private equity funds will also invest in their own vehicles, typically providing between 1–5% of the overall capital.

Often private equity fund managers will employ the services of external fundraising teams known as placement agents in order to raise capital for their vehicles. The use of placement agents has grown over the past few years, with 40% of funds closed in 2006 employing their services, according to Preqin ltd (formerly known as Private Equity Intelligence). Placement agents will approach potential investors on behalf of the fund manager, and will typically take a fee of around 1% of the commitments that they are able to garner.

The amount of time that a private equity firm spends raising capital varies depending on the level of interest among investors, which is defined by current market conditions and also the track record of previous funds raised by the firm in question. Firms can spend as little as one or two months raising capital when they are able to reach the target that they set for their funds relatively easily, often through gaining commitments from existing investors in their previous funds, or where strong past performance leads to strong levels of investor interest. Other managers may find fundraising taking considerably longer, with managers of less popular fund types (such as European venture fund managers in the current climate) finding the fundraising process more tough. It is not unheard of for funds to spend as long as two years on the road seeking capital, although the majority of fund managers will complete fundraising within nine months to fifteen months.

Once a fund has reached its fundraising target, it will have a final close. After this point it is not normally possible for new investors to invest in the fund, unless they were to purchase an interest in the fund on the secondary market.

Size of industry

A record $686bn of private equity was invested globally in 2007, up over a third on the previous year and more than twice the total invested in 2005. Private equity fund raising also surpassed prior years in 2007 with $494bn raised, up 10% on 2006. Despite growing turbulence in the financial markets in the latter part of the year, activity was split equally between the first and second half of the year. Buyouts further increased their share of investments to 89% from a fifth in 2000. Early indicators show that activity is down in the first half of 2008 in comparison to the same period in 2007. The contraction in the credit markets caused by the sub-prime crisis, triggered a slowdown in private equity financing and it became more difficult for private equity firms to obtain debt financing from banks to complete private equity deals.

The regional breakdown of private equity activity shows that in 2007, North America accounted for 71% of global private equity investments (up from 66% in 2000) and 65% of funds raised (down from 68%) (Table 1, Chart 2). Between 2000 and 2007, Europe’s share of investments fell from 20% to 15% and funds raised from 25% to 22%. This was largely a result of stronger buyout market activity in US than in Europe. Between 2000 and 2007 there was a rise in the importance of Asia-Pacific and emerging markets as investment destinations, particularly China, Singapore, South Korea and India. Asia-Pacific’s share of funds raised increased from 6% to 10% during this period while its share of investments remained unchanged at around 12%. [45]

The biggest fund type in terms of commitments garnered was buyout, with 188 funds raising an aggregate $212 billion. So-called mega buyout funds contributed a significant proportion of this amount, with the ten largest funds of 2006 raising $101 billion alone—23% of the global total for 2006. Other strong performers included real estate funds, which grew 30% from already strong 2005 levels, raising an aggregate $63 billion globally. The only fund type to not perform so well was venture, which saw a drop of 10% from 2005 levels.

In terms of the regional split of fundraising, the majority of funds raised in 2006 were focusing on the American market, with 62% of capital raised in 2006 focusing on the US. European focused funds account for 26% of the global total, while funds focusing on Asia and the Rest of World accounted for the remaining 11%.

Venture capital is considered a subset of private equity focused on investments in new and maturing companies.

Mezzanine capital is similar class of alternative investment focused on structured debt securities in private companies.

Private equity fund performance

In the past the performance of private equity funds has been relatively difficult to track, as private equity firms are under no obligation to publicly reveal the returns that they have achieved from their investments. In the majority of cases the only groups with knowledge of fund performance were investors in the funds, academic institutes (as CEPRES Center of Private Equity Research) and the firms themselves, making comparisons between various different firms, and the establishment of market benchmarks to be a difficult challenge.

The application of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in certain states in the United States has made certain performance data more readily available. Specifically, FOIA has required certain public agencies to disclose private equity performance data directly on the their websites[46]. In the United Kingdom, the second largest market for private equity, more data has become available since the 2007 publication of the David Walker Guidelines for Disclosure and Transparency in Private Equity[47].

The performance of the private equity industry over the past few years differs between funds of different types. Buyout and real estate funds have both performed strongly in the past few years (i.e., from 2003-2007) in comparison with other asset classes such as public equities. In contrast other fund investment types, venture capital most notably, have not shown similarly robust performance.

Within each investment type, manager selection (i.e., identifying private equity firms capable of generating above average performance) is a key determinant of an individual investor's performance. Historically, performance of the top and bottom quartile managers has varied dramatically and institutional investors conduct extensive due diligence in order to assess prospective performance of a new private equity fund.

It is challenging to compare private equity performance to public equity performance, in particular because private equity fund investments are drawn and returned over time as investments are made and subsequently realized. One method, first published in 1994, is the Long and Nickels Index Comparison Method (ICM). Another method which is gaining ground in academia is the public market equivalent or profitability index. The profitability index determines the investment in public market investments required to earn a target profit from a portfolio of private equity fund investments.[48]

See also

- History of private equity and venture capital

- Private equity firm

- Private equity fund

- Financial sponsor

- Leveraged buyout

- Management buyout

- Venture capital

- Mezzanine capital

- Private equity secondary market (Secondaries)

- Publicly traded private equity

- Private investment in public equity

- Taxation of Private Equity and Hedge Funds

References and notes

- Cendrowski, Harry (2008). Private Equity: Governance and Operations Assessment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-17846-1.

- Maxwell, Ray (2007). Private Equity Funds: A Practical Guide for Investors. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-02818-6.

- Leleux, Benoit; Hans van Swaay (2006). Growth at All Costs: Private Equity as Capitalism on Steroids. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-403-98634-7.

- Fraser-Sampson, Guy (2007). Private Equity as an Asset Class. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-06645-8.

- Bassi, Iggy; Jeremy Grant (2006). Structuring European Private Equity. London: Euromoney Books. ISBN 1-843-74262-4.

- Thorsten, Gröne (2005). Private Equity in Germany — Evaluation of the Value Creation Potential for German Mid-Cap Companies. Stuttgart: Ibidem-Verl. ISBN 3-898-21620-9.

- Lerner, Joshua (2000). Venture Capital and Private Equity: A Casebook. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-32286-5.

- Grabenwarter, Ulrich; Tom Weidig (2005). Exposed to the J Curve: Understanding and Managing Private Equity Fund Investments. London: Euromoney Institutional Investor. ISBN 1-84374-149-0.

- ↑ This article uses the American definitions for most terms. The British Venture Capital Association provides An Introduction to Private Equity, including differences in terminology.

- ↑ In the United Kingdom, venture capital is often used instead of private equity to describe the overal asset class and investment strategy described here as private equity.

- ↑ A Secondary Market for Private Equity is Born, The Industry Standard, 28 August 2001

- ↑ Investors Scramble for Infrastructure (Fiancial News, 2008)

- ↑ Is It Time to Add a Parking Lot to Your Portfolio? (New York Times, 2006

- ↑ [Buyout firms put energy infrastructure in pipeline] (MSN Money, 2008)

- ↑ Merchant Banking: Past and Present

- ↑ Wilson, John. The New Ventures, Inside the High Stakes World of Venture Capital.

- ↑ WGBH Public Broadcasting Service, “Who made America?"-Georges Doriot”

- ↑ Joseph W. Bartlett, "What Is Venture Capital?"

- ↑ The Future of Securities Regulation speech by Brian G. Cartwright, General Counsel U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. University of Pennsylvania Law School Institute for Law and Economics Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 24, 2007.

- ↑ On January 21, 1955, McLean Industries, Inc. purchased the capital stock of Pan Atlantic Steamship Corporation and Gulf Florida Terminal Company, Inc. from Waterman Steamship Corporation. In May McLean Industries, Inc. completed the acquisition of the common stock of Waterman Steamship Corporation from its founders and other stockholders.

- ↑ Marc Levinson, The Box, How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, pp. 44-47 (Princeton Univ. Press 2006). The details of this transaction are set out in ICC Case No. MC-F-5976, McLean Trucking Company and Pan-Atlantic American Steamship Corporation--Investigation of Control, July 8, 1957.

- ↑ Trehan, R. (2006). The History Of Leveraged Buyouts. December 4, 2006. Accessed May 22, 2008

- ↑ The History of Private Equity (Investment U, The Oxford Club

- ↑ Burrough, Bryan. Barbarians at the Gate. New York : Harper & Row, 1990, p. 133-136

- ↑ Taylor, Alexander L. "Buyout Binge". TIME magazine, Jul. 16, 1984.

- ↑ Opler, T. and Titman, S. "The determinants of leveraged buyout activity: Free cash flow vs. financial distress costs." Journal of Finance, 1993.

- ↑ 10 Questions for Carl Icahn by Barbara Kiviat, TIME magazine, Feb. 15, 2007

- ↑ TWA - Death Of A Legend by Elaine X. Grant, St Louis Magazine, Oct 2005

- ↑ Game of Greed (TIME magazine, 1988)

- ↑ Wallace, Anise C. "Nabisco Refinance Plan Set." The New York Times, July 16, 1990.

- ↑ Stone, Dan G. (1990). April Fools: An Insider's Account of the Rise and Collapse of Drexel Burnham. New York City: Donald I. Fine. ISBN 1556112289.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Den of Thieves. Stewart, J. B. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991. ISBN 0-671-63802-5.

- ↑ New Street Capital Inc. - Company Profile, Information, Business Description, History, Background Information on New Street Capital Inc at ReferenceForBusiness.com

- ↑ SORKIN, ANDREW ROSS and ROZHON, TRACIE. "Three Firms Are Said to Buy Toys 'R' Us for $6 Billion ." New York Times, March 17, 2005.

- ↑ ANDREW ROSS SORKIN and DANNY HAKIM. "Ford Said to Be Ready to Pursue a Hertz Sale." New York Times, September 8, 2005

- ↑ PETERS, JEREMY W. "Ford Completes Sale of Hertz to 3 Firms." New York Times, September 13, 2005

- ↑ SORKIN, ANDREW ROSS. "Sony-Led Group Makes a Late Bid to Wrest MGM From Time Warner." New York Times, September 14, 2004

- ↑ "Capital Firms Agree to Buy SunGard Data in Cash Deal." Bloomberg, March 29, 2005

- ↑ Samuelson, Robert J. "The Private Equity Boom". The Washington Post, March 15, 2007.

- ↑ Dow Jones Private Equity Analyst as referenced in U.S. private-equity funds break record Associated Press, January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Dow Jones Private Equity Analyst as referenced in Private equity fund raising up in 2007: report, Reuters, January 8, 2008.

- ↑ SORKIN, ANDREW ROSS. "HCA Buyout Highlights Era of Going Private." New York Times, July 25, 2006.

- ↑ WERDIGIER, JULIA. "Equity Firm Wins Bidding for a Retailer, Alliance Boots." New York Times, April 25, 2007

- ↑ Lonkevich, Dan and Klump, Edward. KKR, Texas Pacific Will Acquire TXU for $45 Billion Bloomberg, February 26, 2007.

- ↑ SORKIN, ANDREW ROSS and de la MERCED, MICHAEL J. "Private Equity Investors Hint at Cool Down." New York Times, June 26, 2007

- ↑ SORKIN, ANDREW ROSS. "Sorting Through the Buyout Freezeout." New York Times, August 12, 2007.

- ↑ Turmoil in the marketsThe Economist July 27, 2007

- ↑ Michael S. Long & Thomas A. Bryant (2007) Valuing the Closely Held Firm New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN13: 9780195301465 [1]

- ↑ Top 50 PE funds from Private equity international

- ↑ http://money.cnn.com/2007/02/16/magazines/fortune/top10.fortune/index.htm

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2007/feb/08/privateequity.usnews

- ↑ http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/markets/united_states/article711293.ece

- ↑ Private Equity 2008.pdf

- ↑ In the United States, FOIA is individually legislated at the state level, and so disclosed private equity performance data will vary widely. Notable examples of agencies that are mandated to disclose private equity information include CalPERS, CalSTRS and Pennsylvania State Employees Retirement System and the Ohio Bureau of Workers' Compensation

- ↑ Guidelines for Disclosure and Transparency in Private Equity

- ↑ See Phalippou and Gottschalg's 2007 paper, Performance of Private Equity Fundsfor an overview of the profitability index

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||