Presidential system

A presidential system is a system of government where an executive branch exists and presides (hence the name) separately from the legislature, to which it is not accountable and which cannot, in normal circumstances, dismiss it. [1]

It owes its origins to the medieval monarchies of France, England and Scotland in which executive authority was vested in the Crown, not in meetings of the estates of the realm (i.e., parliament): the Estates-General of France, the Parliament of England or the Estates of Scotland. The concept of separate spheres of influence of the executive and legislature was copied in the Constitution of the United States, with the creation of the office of President of the United States. Perhaps ironically, in England and Scotland (since 1707 as the Kingdom of Great Britain, and since 1801 as the United Kingdom) the power of a separate executive waned to a ceremonial role and a new executive, answerable to parliament, evolved while the power of the United States's separated executive increased. This has given rise to criticism of the United States presidency as an "imperial presidency" though some analysts dispute the existence of an absolute separation, referring to the concept of "separate institutions sharing power".

Although not exclusive to republics, and applied in the case of absolute monarchies, the term is often associated with republican systems in the Americas.

Contents |

Republican presidential systems

The defining characteristic of a republican presidential system is how the executive is elected, but nearly all presidential systems share the following features:

- The president does not propose bills. However, in systems such as that of the United States, the president has the power to veto acts of the legislature and, in turn, a supermajority of legislators may act to override the veto. This practice is derived from the British tradition of royal assent in which an act of parliament cannot come into effect without the assent of the monarch.

- The president has a fixed term of office. Elections are held at scheduled times, and cannot be triggered by a vote of confidence or other such parliamentary procedures. In some countries, including the United States, there is an exception to this rule, which provides for the removal of a president in the event that they are found to have broken a law.

- The executive branch is unipersonal. Members of the cabinet serve at the pleasure of the president and must carry out the policies of the executive and legislative branches. However, presidential systems frequently require legislative approval of presidential nominations to the cabinet as well as various governmental posts such as judges. A president generally has power to direct members of the cabinet, military or any officer or employee of the executive branch, but generally has no power to dismiss or give orders to judges.

- The power to pardon or commute sentences of convicted criminals is often in the hands of the heads of state in governments that separate their legislative and executive branches of government.

- The term presidential system is often used in contrast to cabinet government which is usually a feature of parliamentarism. There also exists a kind of intermediate—the semi-presidential system.

- Countries with congressional and presidential systems include the United States, Indonesia, the Philippines, Mexico, South Korea, Argentina and most countries in South America, as well as much of Africa and the Central Asian Republics. The widespread use of presidentialism in the Americas has caused political scientists to dub the Americas as "the continent of presidentialism".

- Countries that feature a presidential system of government are not the exclusive users of the title of President or the republican form of government. For example, a dictator, who may or may not have been popularly or legitimately elected may be and often is called a president. Likewise, many parliamentary democracies are formally styled republics and have presidents, a position which is largely ceremonial; notable examples include Israel, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, Germany and Ireland (See Parliamentary republic).

Characteristics of presidents

Some national presidents are "figurehead" heads of state, like constitutional monarchs, and not active executive heads of government. In a full-fledged presidential system, a president is chosen by the people to be the head of the executive branch.

Presidential governments make no distinction between the positions of head of state and head of government, both of which are held by the president. Most parliamentary governments have a symbolic head of state in the form of a president or monarch. That person is responsible for the formalities of state functions as the figurehead while the constitutional prerogatives of head of government are generally exercised by the prime minister. Such figurehead presidents tend to be elected in a much less direct manner than active presidential-system presidents, for example, by a vote of the legislature. A few nations, such as Ireland, do have a popularly elected ceremonial president.

A few countries (e.g., South Africa) have powerful presidents who are elected by the legislature. These presidents are chosen in the same way as a prime minister, yet are heads of both state and government. These executives are titled "president", but are in practice similar to prime ministers. Other countries with the same system include Botswana, the Marshall Islands, and Nauru. Incidentally, the method of legislative vote for president was a part of Madison's Virginia Plan and was seriously considered by the framers of the American Constitution.

Some political scientists consider the conflation of head-of-state and head-of-government duties to be a problem of presidentialism because criticism of the president as head of state is criticism of the state itself.

Presidents in presidential systems are always active participants in the political process, though the extent of their relative power may be influenced by the political makeup of the legislature and whether their supporters or opponents have the dominant position therein. In some presidential systems such as South Korea or the Republic of China (on Taiwan), there is an office of prime minister or premier but, unlike in semi-presidential or parliamentary systems, the premier is responsible to the president rather than to the legislature.

Advantages of presidential systems

Supporters generally claim four basic advantages for presidential systems:

- Direct mandate — in a presidential system, the president is often elected directly by the people. To some, this makes the president's power more legitimate than that of a leader appointed indirectly. In the United States, the president is elected neither directly nor through the legislature, but by an electoral college.

- Separation of powers — a presidential system establishes the presidency and the legislature as two parallel structures. Supporters claim that this arrangement allows each structure to supervise the other, preventing abuses.

- Speed and decisiveness — some argue that a president with strong powers can usually enact changes quickly. However, others argue that the separation of powers slows the system down.

- Stability — a president, by virtue of a fixed term, may provide more stability than a prime minister who can be dismissed at any time.

Direct mandate

A prime minister is usually chosen by a few individuals of the legislature, while a president is usually chosen by the people. According to supporters of the presidential system, a popularly elected leadership is inherently more democratic than a leadership chosen by a legislative body, even if the legislative body was itself elected, to rule.

Through making more than one electoral choice, voters in a presidential system can more accurately indicate their policy preferences. For example, in the United States of America, some political scientists interpret the late Cold War tendency to elect a Democratic Congress and a Republican president as the choice for a Republican foreign policy and a Democratic domestic policy.

It is also stated that the direct mandate of a president makes him or her more accountable. The reasoning behind this argument is that a prime minister is "shielded" from public opinion by the apparatus of state, being several steps removed. Critics of this view note, however, that presidents cannot typically be removed from power when their policies no longer reflect the wishes of the citizenry. (In the United States, presidents can only be removed by an Impeachment trial for "High Crimes and Misdemeanors," whereas prime ministers can typically be removed if they fail a motion of confidence in their government.)

Separation of powers

The fact that a presidential system separates the executive from the legislature is sometimes held up as an advantage, in that each branch may scrutinize the actions of the other. In a parliamentary system, the executive is drawn from the legislature, making criticism of one by the other considerably less likely. A formal condemnation of the executive by the legislature is often regarded to be a vote of no confidence. According to supporters of the presidential system, the lack of checks and balances means that misconduct by a prime minister may never be discovered. Writing about Watergate, Woodrow Wyatt, a former MP in the UK, said "don't think a Watergate couldn't happen here, you just wouldn't hear about it". (ibid)

Critics respond that if a presidential system's legislature is controlled by the president's party, the same situation exists. Proponents note that even in such a situation a legislator from the president's party is in a better position to criticize the president or his policies should he deem it necessary, since a president is immune to the effects of a motion of no confidence. In parliamentary systems, party discipline is much more strictly enforced. If a parliamentary backbencher publicly criticizes the executive or its policies to any significant extent then he/she faces a much higher prospect of losing his/her party's nomination, or even outright expulsion from the party.

Despite the existence of the no confidence vote, in practice, it is extremely difficult to stop a prime minister or cabinet that has made its decision. To vote down important legislation that has been proposed by the cabinet is considered to be a vote of no confidence is thus means the government falls and new elections must be held, a consequence few backbenchers are willing to endure. Hence, a no confidence vote in some parliamentary countries, like Britain, only occurs a few times in a century. In 1931, David Lloyd George told a select committee: "Parliament has really no control over the executive; it is a pure fiction." (Schlesinger 1982)

Speed and decisiveness

Some supporters of presidential systems claim that presidential systems can respond more rapidly to emerging situations than parliamentary ones. A prime minister, when taking action, needs to retain the support of the legislature, but a president is often less constrained. In Why England Slept, future president John F. Kennedy said that Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain were constrained by the need to maintain the confidence of the Commons.

Other supporters of presidential systems sometimes argue in the exact opposite direction, however, saying that presidential systems can slow decision-making to beneficial ends. Divided government, where the presidency and the legislature are controlled by different parties, is said to restrain the excesses of both parties, and guarantee bipartisan input into legislation. In the United States, Republican Congressman Bill Frenzel wrote in 1995:

- There are some of us who think gridlock is the best thing since indoor plumbing. Gridlock is the natural gift the Framers of the Constitution gave us so that the country would not be subjected to policy swings resulting from the whimsy of the public. And the competition - whether multi-branch, multi-level, or multi-house - is important to those checks and balances and to our ongoing kind of centrist government. Thank heaven we do not have a government that nationalizes one year and privatizes next year, and so on ad infinitum. (Checks and Balances, 8)

Stability

Although most parliamentary governments go long periods of time without a no confidence vote, Italy, Israel , and the French Fourth Republic have all experienced difficulties maintaining stability. When parliamentary systems have multiple parties and governments are forced to rely on coalitions, as they do in nations that use a system of proportional representation, extremist parties can theoretically use the threat of leaving a coalition to further their agendas.

Many people consider presidential systems to be more able to survive emergencies. A country under enormous stress may, supporters argue, be better off being led by a president with a fixed term than rotating premierships. France during the Algerian controversy switched to a semi-presidential system as did Sri Lanka during its civil war, while Israel experimented with a directly elected prime minister in 1992. In France and Sri Lanka, the results are widely considered to have been positive. However, in the case of Israel, an unprecedented proliferation of smaller parties occurred, leading to the restoration of the previous system of selecting a prime minister.

The fact that elections are fixed in a presidential system is considered to be a welcome "check" on the powers of the executive, contrasting parliamentary systems, which often allow the prime minister to call elections whenever he sees fit, or orchestrate his own vote of no confidence to trigger an election when he cannot get a legislative item passed. The presidential model is said to discourage this sort of opportunism, and instead force the executive to operate within the confines of a term he cannot alter to suit his own needs. Theoretically, if a president's positions and actions have had a positive impact on their respective country, then it is likely that their party's candidate (possibly they) will be elected for another term in office.

Criticism

Critics generally claim three basic disadvantages for presidential systems:

- Tendency towards authoritarianism — some political scientists say that presidentialism is not constitutionally stable. According to some political scientists, such as Fred Riggs, presidentialism has fallen into authoritarianism in nearly every country it has been attempted.

- Separation of powers — a presidential system establishes the presidency and the legislature as two parallel structures. Critics argue that this creates undesirable gridlock, and that it reduces accountability by allowing the president and the legislature to shift blame to each other.

- Impediments to leadership change — it is claimed that the difficulty in removing an unsuitable president from office before his or her term has expired represents a significant problem.

Tendency towards authoritarianism

Winning the presidency is a winner-take-all, zero-sum prize. A prime minister who does not enjoy a majority in the legislature will have to either form a coalition or, if he is able to lead a minority government, govern in a manner acceptable to at least some of the opposition parties. Even if the prime minister leads a majority government, he must still govern within (perhaps unwritten) constraints as determined by the members of his party - a premier in this situation is often at greater risk of losing his party leadership than his party is at risk of losing the next election. On the other hand, once elected a president cannot only marginalize the influence of other parties, but can exclude rival factions in his own party as well, or even leave the party whose ticket he was elected under. The president can thus rule without any allies for the duration of one or possibly consecutive terms, a worrisome situation for many interest groups. Juan Linz argues that

- The danger that zero-sum presidential elections pose is compounded by the rigidity of the president's fixed term in office. Winners and losers are sharply defined for the entire period of the presidential mandate. . . losers must wait four or five years without any access to executive power and patronage. The zero-sum game in presidential regimes raises the stakes of presidential elections and inevitably exacerbates their attendant tension and polarization.

Constitutions that only require plurality support are said to be especially undesirable, as significant power can be vested in a person who does not enjoy support from a majority of the population.

Some political scientists go further, and argue that presidential systems have difficulty sustaining democratic practices, noting that presidentialism has slipped into authoritarianism in many of the countries in which it has been implemented. Seymour Martin Lipset and others are careful to point out that this has taken place in political cultures not conducive to democracy, and that militaries have tended to play a prominent role in most of these countries. Nevertheless, certain aspects of the presidential system may have played a role in some situations.

In a presidential system, the legislature and the president have equally valid mandates from the public. There is often no way to reconcile conflict between the branches of government. When president and legislature are in disagreement and government is not working effectively, there is a powerful incentive to employ extra-constitutional maneuvres to break the deadlock.

Ecuador is sometimes presented as a case study of democratic failures over the past quarter-century. Presidents have ignored the legislature or bypassed it altogether. One president had the National Assembly teargassed, while another was kidnapped by paratroopers until he agreed to certain congressional demands. From 1979 through 1988, Ecuador staggered through a succession of executive-legislative confrontations that created a near permanent crisis atmosphere in the policy. In 1984, President León Febres Cordero tried to physically bar new Congressionally-appointed supreme court appointees from taking their seats. In Brazil, presidents have accomplished their objectives by creating executive agencies over which Congress had no say.

It should be noted that this alleged authoritarian tendency is often best seen in unitary states that have presidential systems. Federal states, with multiple state (or provincial) governments that are semi-sovereign, provide additional checks on authoritarian tendencies. This can be seen in the United States, where there are 50 states, each semi-sovereign, each having their own 3 branch elected government (governor, legislature, court system), police, emergency response system, and military force. If an extreme extraconstitutional action, such as the President dissolving the Congress, occurred within the Federal government of the United States, it would not necessarily result in the President being able to rule dictatorially since he or she would have to deal with the 50 state governments.

Separation of powers

Presidential systems are said by critics not to offer voters the kind of accountability seen in parliamentary systems. It is easy for either the president or Congress to escape blame by blaming the other. Describing the United States, former Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon said "the president blames Congress, the Congress blames the president, and the public remains confused and disgusted with government in Washington".

In Congressional Government, Woodrow Wilson asked,

- . . . how is the schoolmaster, the nation, to know which boy needs the whipping? . . . Power and strict accountability for its use are the essential constituents of good government. . . . It is, therefore, manifestly a radical defect in our federal system that it parcels out power and confuses responsibility as it does. The main purpose of the Convention of 1787 seems to have been to accomplish this grievous mistake. The 'literary theory' of checks and balances is simply a consistent account of what our constitution makers tried to do; and those checks and balances have proved mischievous just to the extent which they have succeeded in establishing themselves . . . [the Framers] would be the first to admit that the only fruit of dividing power had been to make it irresponsible.

Consider the example of the increase in the federal debt of the United States that occurred during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Arguably, the deficits were the product of a bargain between President Reagan and Speaker of the House of Representatives Tip O'Neill: O'Neill agreed not to oppose Reagan's tax cuts if Reagan would sign the Democrats' budget. Each side could claim to be displeased with the debt, plausibly blame the other side for the deficit, and still tout its own success.

On the other hand, many observers believe that federal budget surpluses of the late 1990s in the United States were a direct result of divided government. A Republican Congress refused to allow Democratic President Bill Clinton to increase domestic spending, while Clinton refused to allow Congress to cut taxes. The combination of spending restraint and high revenues led to the elimination of the annual budget deficit.

Impediments to leadership change

Another alleged problem of presidentialism is that it is often difficult to remove a president from office early. Even if a president is "proved to be inefficient, even if he becomes unpopular, even if his policy is unacceptable to the majority of his countrymen, he and his methods must be endured until the moment comes for a new election." (Balfour, intro to the English Constitution). Consider John Tyler, who only became president because William Henry Harrison had died after thirty days. Tyler refused to sign Whig legislation, was loathed by his nominal party, but remained firmly in control of the executive branch. Since there is no legal way to remove an unpopular president, many presidential countries have experienced military coups to remove a leader who is said to have lost his mandate.

In parliamentary systems, unpopular leaders such as Tyler can be quickly removed by a vote of no confidence, a procedure which is reckoned to be a "pressure release valve" for political tension. Votes of no confidence are easier to achieve in minority government situations, but even if the unpopular leader heads a majority government, nonetheless he is often in a far less secure position than a president. Removing a president through impeachment is a process mandated by the constitution and is usually made into a very difficult process, by comparison the process of removing a party leader is governed by the (often much less formal) rules of the party in question. Nearly all parties (including governing parties) have a relatively simple and straightforward process for removing their leaders. If a premier sustains a serious enough blow to his/her popularity and refuses to resign on his/her own prior to the next election, then members of his/her party face the prospect of losing their seats. So other prominent party members have a very strong incentive to initiate a leadership challenge in hopes of mitigating damage to the party. More often than not, a premier facing a serious challenge will resolve to save face by resigning before he/she is formally removed - Margaret Thatcher's relinquishing of her premiership being a prominent, recent example.

In The English Constitution, Walter Bagehot criticized presidentialism because it does not allow a transfer in power in the event of an emergency.

- Under a cabinet constitution at a sudden emergency the people can choose a ruler for the occasion. It is quite possible and even likely that he would not be ruler before the occasion. The great qualities, the imperious will, the rapid energy, the eager nature fit for a great crisis are not required - are impediments- in common times. A Lord Liverpool is better in everyday politics than a Chatham- a Louis Philippe far better than a Napoleon. By the structure of the world we want, at the sudden occurrence of a grave tempest, to change the helmsman - to replace the pilot of the calm by the pilot of the storm.

- But under a presidential government you can do nothing of the kind. The American government calls itself a government of the supreme people; but at a quick crisis, the time when a sovereign power is most needed, you cannot find the supreme people. You have got a congress elected for one fixed period, going out perhaps by fixed installments, which cannot be accelerated or retarded - you have a president chosen for a fixed period, and immovable during that period: . . there is no elastic element. . . you have bespoken your government in advance, and whether it is what you want or not, by law you must keep it . . . (The English Constitution, the Cabinet.)

Years later, Bagehot's observation came to life during World War II, when Neville Chamberlain was replaced with Winston Churchill.

Finally, many have criticized presidential systems for their alleged slowness in responding to their citizens' needs. Often, the checks and balances make action extremely difficult. Walter Bagehot said of the American system "the executive is crippled by not getting the law it needs, and the legislature is spoiled by having to act without responsibility: the executive becomes unfit for its name, since it cannot execute what it decides on; the legislature is demoralized by liberty, by taking decisions of others [and not itself] will suffer the effects". (ibid.)

Differences from a cabinet system

A number of key theoretical differences exist between a presidential and a cabinet system:

- In a presidential system, the central principle is that the legislative and executive branches of government should be separate. This leads to the separate election of president, who is elected to office for a fixed term, and only removable for gross misdemeanor by impeachment and dismissal. In addition he or she does not need to choose cabinet members commanding the support of the legislature. By contrast, in parliamentarism, the executive branch is led by a council of ministers, headed by a Prime Minister, who are directly accountable to the legislature and often have their background in the legislature (regardless of whether it is called a "parliament", a "diet", or a "chamber").

- As with the president's set term of office, the legislature also exists for a set term of office and cannot be dissolved ahead of schedule. By contrast, in parliamentary systems, the legislature can typically be dissolved at any stage during its life by the head of state, usually on the advice of either Prime Minister alone, by the Prime Minister and cabinet, or by the cabinet.

- In a presidential system, the president usually has special privileges in the enactment of legislation, namely the possession of a power of veto over legislation of bills, in some cases subject to the power of the legislature by weighed majority to override the veto. However, it is extremely rare for the president to have the power to directly propose laws, or cast a vote on legislation. The legislature and the president are thus expected to serve as checks and balances on each other's powers.

- Presidential system presidents may also be given a great deal of constitutional authority in the exercise of the office of Commander in Chief, a constitutional title given to most presidents. In addition, the presidential power to receive ambassadors as head of state is usually interpreted as giving the president broad powers to conduct foreign policy. Though semi-presidential systems may reduce a president's power over day to day government affairs, semi-presidential systems commonly give the president power over foreign policy.

Presidential systems also have fewer ideological parties than parliamentary systems. Sometimes in the United States, the policies preferred by the two parties have been very similar (but see also polarization). In the 1950s, during the leadership of Lyndon Johnson, the Senate Democrats included the right-most members of the chamber - Harry Byrd and Strom Thurmond, and the left-most members - Paul Douglas and Herbert Lehman. This pattern prevails in Latin American presidential democracies and the Philippines as well.

Overlapping Elements

In practice, elements of both systems overlap. Though a president in a presidential system does not have to choose a government answerable to the legislature, the legislature may have the right to scrutinize his or her appointments to high governmental office, with the right, on some occasions, to block an appointment. In the United States, many appointments must be confirmed by the Senate. By contrast, though answerable to parliament, a parliamentary system's cabinet may be able to make use of the parliamentary 'whip' (an obligation on party members in parliament to vote with their party) to control and dominate parliament, reducing parliament's ability to control the government.

Some countries, such as France have similarly evolved to such a degree that they can no longer be accurately described as either presidential or parliamentary-style governments, and are instead grouped under the category of semi-presidential system.

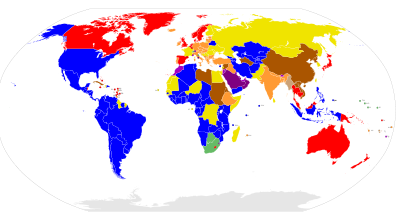

Democracies with a presidential system of government

Footnotes

- ↑ The legislature may retain the right, in extreme cases, to dismiss the executive, often through a process called impeachment or, as happened in England in 1649, through the abolition of the Crown (see Commonwealth of England). However, such an intervention is seen as so rare (only two United States presidents were impeached — charged with misconduct — and neither was convicted, while no impeachment has occurred in what is now the United Kingdom for hundreds of years) as not to contradict the central tenet of presidentialism, that in normal circumstances using normal means the legislature cannot dismiss the executive.