Sheaf (mathematics)

In mathematics, a sheaf is a tool for systematically tracking locally defined data attached to the open sets of a topological space. The data can be restricted to smaller open sets, and the data assigned to an open set is equivalent to all collections of compatible data assigned to collections of smaller open sets covering the original one. For example, such data can consist of the rings of continuous or smooth real-valued functions defined on each open set. Sheaves are by design quite general and abstract objects, and their correct definition is rather technical. They exist in several varieties such as sheaves of sets or sheaves of rings, depending on the type of data assigned to open sets.

There are also maps (or morphisms) from one sheaf to another; sheaves (of a specific type, such as sheaves of Abelian groups) with their morphisms on a fixed topological space form a category. On the other hand, to each continuous map there is associated both a direct image functor, taking sheaves and their morphisms on the domain to sheaves and morphisms on the codomain, and an inverse image functor operating in the opposite direction. These functors, and certain variants of theirs, are essential parts of sheaf theory.

Due to their general nature and versatility, sheaves have several applications in topology and especially in algebraic and differential geometry. First, several geometric structures such as that of a differentiable manifold or a scheme can be expressed in terms of a sheaf of rings on the space. In such contexts several geometric constructions such as vector bundles or divisors are naturally specified in terms of sheaves. Second, sheaves provide the framework for a very general cohomology theory, which encompasses also the "usual" topological cohomology theories such as singular cohomology. Especially in algebraic geometry and the theory of complex manifolds, sheaf cohomology provides a powerful link between topological and geometric properties of spaces. Sheaves also provide the basis for the theory of D-modules, which provide applications to the theory of differential equations. In addition, generalisations of sheaves to more general settings than topological spaces have provided applications to mathematical logic and number theory.

Introduction

In topology, differential geometry and algebraic geometry, several structures defined on a topological space (which can additionally be, e.g., a differentiable manifold) can be naturally localised or restricted to open subsets of the space: typical examples include continuous real or complex-valued functions, n times differentiable (real or complex-valued) functions, bounded real-valued functions, vector fields, and sections of any vector bundle on the space.

Presheaves formalise the situation common to the examples above: a presheaf (of sets) on a topological space is a structure which associates to each open set U of the space a set F(U) of "sections" on U, and to each open set V included in another open set U a map F(U) → F(V) giving restrictions of sections over U to V. Each of the examples above defines a presheaf with restrictions of functions, vector fields and sections of a vector bundle having the obvious meaning. Moreover, in each of these examples the sets of sections have additional algebraic structure: pointwise operations make them Abelian groups, and in the examples of real and complex-valued functions the sets of sections have even a ring structure. In addition, in each example the restriction maps are homomorphisms of the corresponding algebraic structure. This observation leads to the natural definition of presheaves with additional algebraic structure such as presheaves of groups, of Abelian groups, of rings: section sets are required to have the specified algebraic structure, and the restrictions are required to be homomorphisms. Thus for example continuous real-valued functions on a topological space form a presheaf of rings on the space.

Given a presheaf, a natural question to ask is to what extent its sections over an open set U are specified by their restrictions to smaller open sets Vi of an open cover of U. A presheaf is separated if its sections are "locally determined": whenever two sections over U coincide when restricted to each of Vi, the two sections are identical. All examples of presheaves discussed above are separated, since in each case the sections are specified by their values at the points of the underlying space. Finally, a separated presheaf is a sheaf if compatible sections can be glued together, i.e., whenever there is a section of the presheaf over each of the covering sets Vi, chosen so that they match on the overlaps of the covering sets, these sections correspond to a (unique) section on U, of which they are restrictions. It is easy to verify that all examples above except the presheaf of bounded functions are in fact sheaves: in all cases the criterion of being a section of the presheaf is local in a sense that it is enough to verify it in an arbitrary neighbourhood of each point.

On the other hand, it is clear that a function can be bounded on each set of an (infinite) open cover of a space without being bounded on all of the space; thus bounded functions provide an example of a presheaf that in general fails to be a sheaf. Another example of a presheaf that fails to be a sheaf is the constant presheaf that associates the same fixed set (or Abelian group, or a ring,...) to each open set: it follows from the glueing property of sheaves that sections on a disjoint union of two open sets is the Cartesian product of the sections over the two open sets. The correct way to define the constant sheaf FA (associated to for instance a set A) on a topological space is to require sections on an open set U to be continuous maps from U to A equipped with the discrete topology; then in particular FA(U) = A for connected U.

Maps between presheaves and sheaves (called morphisms) consist of maps between the sets of sections over each open set of the underlying space, compatible with restrictions of sections. If the presheaves or sheaves considered are provided with additional algebraic structure, these maps are assumed to be homomorphisms.

Presheaves and sheaves are typically denoted by capital letters, F being particularly common, presumably for the French word for sheaves, faisceau. Use of script letters such as  is also common.

is also common.

Formal definitions

The first step in defining a sheaf is to define a presheaf, which captures the idea of associating data and restriction maps to the open sets of a topological space. The second step is to require the normalization and gluing axioms. A presheaf which satisfies these axioms is a sheaf.

Presheaves

Let X be a topological space, and let C be a category. Usually C is the category of sets, the category of groups, the category of abelian groups, or the category of commutative rings. A presheaf F on X with values in C is given by the following data:

- For each open set U of X, an object F(U) in C

- For each inclusion of open sets V ⊆ U, a morphism resV,U : F(U) → F(V) in the category C.

The morphisms resV,U are called restriction morphisms. The restriction morphisms are required to satisfy two properties.

- For every open set U of X, the restriction morphism resU,U : F(U) → F(U) is the identity morphism on F(U).

- If we have three open sets W ⊆ V ⊆ U, then resW,V o resV,U = resW,U.

Informally, the second axiom says it doesn't matter whether we restrict to W in one step or restrict first to V, then to W.

There is a compact way to express the notion of a presheaf in terms of category theory. First we define the category of open sets on X to be the category O(X) whose objects are the open sets of X and whose morphisms are inclusions. Then a C-valued presheaf on X is the same as a contravariant functor from O(X) to C. This definition can be generalized to the case when the source category is not of the form O(X) for any X; see presheaf (category theory).

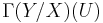

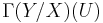

If F is a C-valued presheaf on X, and U is an open subset of X, then F(U) is called the sections of F over U. If C is a concrete category, then each element of F(U) is called a section. A section over X is called a global section. A common notation (used also below) for the restriction resV,U(s) of a section is s|V. This terminology and notation is by analogy with sections of fiber bundles or sections of the étale space of a sheaf; see below. F(U) is also often denoted Γ(U,F), especially in contexts such as sheaf cohomology where U tends to be fixed and F tends to be variable.

Sheaves

The definition is first given for a sheaf with values in a concrete category (one in which the object can be interpreted as sets with possibly additional structure). This definition is more intuitive than the general one, and applies to the most common examples such as sheaves of sets, Abelian groups and rings.

A sheaf with values in a concrete category C is a presheaf with values in C that satisfies the following three axioms:

- (Normalisation) F(∅) is the terminal object of C;

- (Local identity) If (Ui) is an open covering of an open set U, and if s,t ∈ F(U) are such that s|Ui = t|Ui for each set Ui of the covering, then s = t; and

- (Glueing) If (Ui) is an open covering of an open set U, and if for each i there is a section si of F over Ui such that for each pair Ui,Uj of the covering sets the restrictions of si and sj agree on the overlaps: si|Ui∩Uj = sj|Ui∩Uj, then there is a section s ∈ F(U) such that s|Ui = si for each i.

The section s, whose existence is guaranteed by axiom 3, is called the gluing, concatenation, or collation of the sections si. By axiom 2 it is unique. Sections si satisfying the condition of axiom 3 are often called compatible; thus axioms 2 and 3 together state that compatible sections can be uniquely glued together. A further detailed example illustrates the glueing axiom in a simple situation.

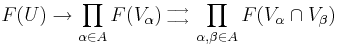

The general definition of a sheaf with values in category C, not necessarily concrete but assumed to have products, can be expressed in a compact manner by means of an exact sequence: consider in C the diagram

,

,

where the first map is the product of the restriction maps

- resVα,U:F(U)→F(Vα)

and the pair of arrows the products of the two sets of restrictions

- resVα∩Vβ,Vα:F(Vα)→F(Vα∩Vβ)

and

- resVα∩Vβ,Vβ:F(Vβ)→F(Vα∩Vβ).

Now a presheaf F is a sheaf precisely when for each open covering of an open set U by a family Vα of open subsets of U where the first arrow is an equalizer. For a separated presheaf, the first arrow need only be injective. [1]

It can be shown that to specify a sheaf, it is enough to specify its restriction to the open sets of a basis for the topology of the underlying space. Moreover, it can also be shown that it is enough to verify the sheaf axioms above relative to the open sets of a covering. Thus a sheaf can often be defined by giving its values on the open sets of a basis, and verifying the sheaf axioms relative to the basis.

Morphisms

Heuristically speaking, a morphism of sheaves is analogous to a function between them. However, because sheaves contain data relative to every open set of a topological space, a morphism of sheaves is defined as a collection of functions, one for each open set, which satisfy a compatibility condition.

Let F and G be two sheaves on X with values in the category C. A morphism φ : G → F consists of a morphism φ(U) : G(U) → F(U) for each open set U of X, subject to the condition that this morphism is compatible with restrictions. In other words, for every open subset U of an open set V, the following diagram

is commutative.

Recall that we could also express a sheaf as a special kind of functor. In this language, a morphism of sheaves is a natural transformation of the corresponding functors. With this notion of morphism, there is a category of C-valued sheaves on X for any C. The objects are the C-valued sheaves, and the morphisms are morphisms of sheaves. An isomorphism of sheaves is an isomorphism in this category.

It can be proved that an isomorphism of sheaves is an isomorphism on each open set U. In other words, φ is an isomorphism if and only if for each U, φ(U) is an isomorphism. The same is true of monomorphisms, but not of epimorphisms. See sheaf cohomology.

Notice that we did not use the gluing axiom in defining a morphism of sheaves. Consequently, the above definition makes sense for presheaves as well. The category of C-valued presheaves is then a functor category, the category of contravariant functors from O(X) to C.

Examples

Because sheaves encode exactly the data needed to pass between local and global situations, there are many examples of sheaves occurring throughout mathematics. Here are some additional examples of sheaves:

- Any continuous map of topological spaces determines a sheaf of sets. Let f : Y → X be a continuous map. We define a sheaf

on X by setting

on X by setting  equal to the sections U → Y, that is,

equal to the sections U → Y, that is,  is the set of all functions s : U → Y such that fs = idU. Restriction is given by restriction of functions. This sheaf is called the sheaf of sections of f, and it is especially important when f is the projection of a fiber bundle onto its base space. Notice that if the image of f does not contain U, then

is the set of all functions s : U → Y such that fs = idU. Restriction is given by restriction of functions. This sheaf is called the sheaf of sections of f, and it is especially important when f is the projection of a fiber bundle onto its base space. Notice that if the image of f does not contain U, then  is empty. For a concrete example, take

is empty. For a concrete example, take  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.  is the set of branches of the logarithm on

is the set of branches of the logarithm on  .

.

- Fix a point x in X and an object S in a category C. The skyscraper sheaf over x with stalk S is the sheaf Sx defined as follows: If U is an open set containing x, then Sx(U) = S. If U does not contain x, then Sx(U) is the terminal object of C. The restriction maps are either the identity on S, if both open sets contain x, or the unique map from S to the terminal object of C.

Sheaves on manifolds

In the following examples M is an n-dimensional Ck-manifold. The table lists the values of certain sheaves over open subsets U of M and their restriction maps.

| Sheaf | Sections over an open set U | Restriction maps | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

Sheaf of j-times continuously differentiable functions  , j ≤ k , j ≤ k |

Cj-functions U → R | Restriction of functions. | This is a sheaf of rings with addition and multiplication given by pointwise addition and multiplication. When j = k, this sheaf is called the structure sheaf and is denoted  . . |

Sheaf of nonzero k-times continuously differentiable functions  |

Nowhere zero Ck-functions U → R | Restriction of functions. | A sheaf of groups under pointwise multiplication. |

| Cotangent sheaves ΩpM | Differential forms of degree p on U | Restriction of differential forms. | Ω1M and ΩnM are commonly denoted ΩM and ωM, respectively. |

Sheaf of distributions  |

Distributions on U | The dual map to extension of smooth compactly supported functions by zero. | Here M is assumed to be smooth. |

Sheaf of differential operators  |

Finite-order differential operators on U | Restriction of differential operators. | Here M is assumed to be smooth. |

Presheaves which are not sheaves

Here are two examples of presheaves which are not sheaves:

- Let X be the two-point topological space {x, y} with the discrete topology. Define a presheaf F as follows: F(∅) = ∅, F({x}) = R, F({y}) = R, F({x, y}) = R × R × R. The restriction map F({x, y}) → F({x}) is the projection of R × R × R onto its first coordinate, and the restriction map F({x, y}) → F({y}) is the projection of R × R × R onto its second coordinate. F is a presheaf which is not separated: A global section is determined by three numbers, but the values of that section over {x} and {y} determine only two of those numbers. So while we can glue any two sections over {x} and {y}, we cannot glue them uniquely.

- Let X be the real line, and let F(U) be the set of bounded continuous functions on U. This is not a sheaf because it is not always possible to glue. For example, let Ui be the set of all x such that |x| < i. The identity function f(x) = x is bounded on each Ui. Consequently we get a section si on Ui. However, these sections do not glue, because the function f is not bounded on the real line. Consequently F is a presheaf, but not a sheaf. In fact, F is separated because it is a sub-presheaf of the sheaf of continuous functions.

Turning a presheaf into a sheaf

It is frequently useful to take the data contained in a presheaf and to express it as a sheaf. It turns out that there is a best possible way to do this. It takes a presheaf F and produces a new sheaf aF called the sheaving, sheafification or sheaf associated to the presheaf F. a is called the sheaving functor, sheafification functor, or associated sheaf functor. There is a natural morphism of presheaves i : F → aF which has the universal property that for any sheaf G and any morphism of presheaves f : F → G, there is a unique morphism of sheaves  such that

such that  . In fact a is the adjoint functor to the inclusion functor from the category of sheaves to the category of presheaves, and i is the unit of the adjunction.

. In fact a is the adjoint functor to the inclusion functor from the category of sheaves to the category of presheaves, and i is the unit of the adjunction.

Images of sheaves

| Image functors for sheaves |

|

direct image f∗

|

The definition of a morphism on sheaves makes sense only for sheaves on the same space X. This is because the data contained in a sheaf is indexed by the open sets of the space. If we have two sheaves on different spaces, then their data is indexed differently. There is no way to go directly from one set of data to the other.

However, it is possible to move a sheaf from one space to another using a continuous function. Let f : X → Y be a continuous function from a topological space X to a topological space Y. If we have a sheaf on X, we can move it to Y, and vice versa. There are four ways in which sheaves can be moved.

- A sheaf

on X can be moved to Y using the direct image functor

on X can be moved to Y using the direct image functor  or the direct image with proper support functor

or the direct image with proper support functor  .

. - A sheaf

on Y can be moved to X using the inverse image functor

on Y can be moved to X using the inverse image functor  or the twisted inverse image functor

or the twisted inverse image functor  .

.

The twisted inverse image functor  is, in general, only defined as a functor between derived categories. These functors come in adjoint pairs:

is, in general, only defined as a functor between derived categories. These functors come in adjoint pairs:  and

and  are left and right adjoints of each other, and

are left and right adjoints of each other, and  and

and  are left and right adjoints of each other. The functors are intertwined with each other by Grothendieck duality and Verdier duality.

are left and right adjoints of each other. The functors are intertwined with each other by Grothendieck duality and Verdier duality.

There is a different inverse image functor for sheaves of modules over sheaves of rings. This functor is usually denoted  and it is distinct from

and it is distinct from  . See inverse image functor.

. See inverse image functor.

Stalks of a sheaf

The stalk  of a sheaf

of a sheaf  captures the properties of a sheaf "around" a point x ∈ X. Here, "around" means that, conceptually speaking, one looks at smaller and smaller neighborhood of the point. Of course, no single neighborhood will be small enough, so we will have to take a limit of some sort.

captures the properties of a sheaf "around" a point x ∈ X. Here, "around" means that, conceptually speaking, one looks at smaller and smaller neighborhood of the point. Of course, no single neighborhood will be small enough, so we will have to take a limit of some sort.

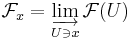

The stalk is defined by

,

,

the direct limit being over all open subsets of X containing the given point x. In other words, an element of the stalk is given by a section over some open neighborhood of x, and two such sections are considered equivalent if their restrictions agree on a smaller neighborhood.

The natural morphism F(U) → Fx takes a section s in F(U) to its germ. This generalises the usual definition of a germ.

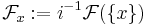

A different way of defining the stalk is

,

,

where i is the inclusion of the one-point space {x} into X. The equivalence follows from the definition of the inverse image.

In many situations, knowing the stalks of a sheaf is enough to control the sheaf itself. For example, whether or not a morphism of sheaves is a monomorphism, epimorphism, or isomorphism can be tested on the stalks. They also find use in constructions such as Godement resolutions.

Ringed spaces and locally ringed spaces

A pair  consisting of a topological space X and a sheaf of rings on X is called a ringed space. Many types of spaces can be defined as certain types of ringed spaces. The sheaf

consisting of a topological space X and a sheaf of rings on X is called a ringed space. Many types of spaces can be defined as certain types of ringed spaces. The sheaf  is called the structure sheaf of the space. A very common situation is when all the stalks of the structure sheaf are local rings, in which case the pair is called a locally ringed space. Here are examples of definitions made in this way:

is called the structure sheaf of the space. A very common situation is when all the stalks of the structure sheaf are local rings, in which case the pair is called a locally ringed space. Here are examples of definitions made in this way:

- An n-dimensional Ck manifold M is a locally ringed space whose structure sheaf is an

-algebra and is locally isomorphic to the sheaf of Ck real-valued functions on Rn.

-algebra and is locally isomorphic to the sheaf of Ck real-valued functions on Rn. - A complex analytic space is a locally ringed space whose structure sheaf is a

-algebra and is locally isomorphic to the vanishing locus of a finite set of holomorphic functions together with the restriction (to the vanishing locus) of the sheaf of holomorphic functions on Cn for some n.

-algebra and is locally isomorphic to the vanishing locus of a finite set of holomorphic functions together with the restriction (to the vanishing locus) of the sheaf of holomorphic functions on Cn for some n. - A scheme is a locally ringed space which is locally isomorphic to the spectrum of a ring.

- A semialgebraic space is a locally ringed space which is locally isomorphic to a semialgebraic set in Euclidean space together with its sheaf of semialgebraic functions.

Sheaves of modules

Let  be a ringed space. A sheaf of modules is a sheaf

be a ringed space. A sheaf of modules is a sheaf  such that on every open set U of X,

such that on every open set U of X,  is an

is an  -module and for every inclusion of open sets V ⊆ U, the restriction map

-module and for every inclusion of open sets V ⊆ U, the restriction map  is a homomorphism of

is a homomorphism of  -modules.

-modules.

Most important geometric objects are sheaves of modules. For example, there is a one-to-one correspondence between vector bundles and locally free sheaves of  -modules. Sheaves of solutions to differential equations are D-modules, that is, modules over the sheaf of differential operators.

-modules. Sheaves of solutions to differential equations are D-modules, that is, modules over the sheaf of differential operators.

A particularly important case are abelian sheaves, which are modules over the constant sheaf  . Every sheaf of modules is an abelian sheaf.

. Every sheaf of modules is an abelian sheaf.

The étale space of a sheaf

In the examples above it was noted that some sheaves occur naturally as sheaves of sections. In fact, all sheaves of sets can be represented as sheaves of sections of a topological space called the étale space. If F is a sheaf over X, then the étale space of F is a topological space E together with a local homeomorphism π: E → X; the sheaf of sections of π is F. E is usually a very strange space, and even if the sheaf F arises from a natural topological situation, E may not have any clear topological interpretation. For example, if F is the sheaf of sections of a continuous function f : Y → X, then E = Y if and only if f is a covering map.

The étale space E is constructed from the stalks of F over X. As a set, it is their disjoint union and π is the obvious map which takes the value x on the stalk of F over x ∈ X. The topology of E is defined as follows. For each element s of F(U) and each x in U, we get a germ of s at x. These germs determine points of E. For any U and s ∈ F(U), the union of these points (for all x ∈ U) is declared to be open in E. Notice that each stalk has the discrete topology. Two morphisms between sheaves determine a continuous map of the corresponding étale spaces which is compatible with the projection maps (in the sense that every germ is mapped to a germ over the same point). This makes the construction into a functor.

This gives an example of an étale space over X. An étale space is a topological space E together with a continuous map π: E → X which is a local homeomorphism such that each fiber of π has the discrete topology. The construction above determines an equivalence of categories between the category of sheaves of sets on X and the category of étalé spaces over X. The construction of an étale space can also be applied to a presheaf, in which case the sheaf of sections of the étale space recovers the sheaf associated to the given presheaf.

The map π is an example of what is sometimes called an étale map. "Étale" here means the same thing as "local homeomorphism". However, the terminology "étale map" is more common in contexts where the right analogue of a local homeomorphism of manifolds is not characterized by the property of being a local homeomorphism. This is the case in algebraic geometry. For more information see the article étale morphism.

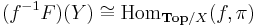

This construction makes all sheaves into representable functors on certain categories of topological spaces. As above, let F be a sheaf on X, let E be its étale space, and let π: E → X be the natural projection. Consider the category Top/X of topological spaces over X, that is, the category of topological spaces together with fixed continuous maps to X. Every object of this space is a continuous map f : Y → X, and a morphism from Y → X to Z → X is a continuous map Y → Z which commutes with the two maps to X. There is a functor Γ from Top/X to the category of sets which takes an object f : Y → X to (f−1F)(Y). For example, if i : U → X is the inclusion of an open subset, then Γ(i) = (i−1F)(U) agrees with the usual F(U), and if i : {x} → X is the inclusion of a point, then Γ({x}) = (i−1F)({x}) is the stalk of F at x. There is a natural isomorphism

which shows that E represents the functor Γ.

The definition of sheaves by étale spaces is older than the definition given earlier in the article. It is still common in some areas of mathematics such as mathematical analysis.

Sheaf cohomology

It was noted above that the functor  preserves isomorphisms and monomorphisms, but not epimorphisms. If F is a sheaf of abelian groups, or more generally a sheaf with values in an abelian category, then

preserves isomorphisms and monomorphisms, but not epimorphisms. If F is a sheaf of abelian groups, or more generally a sheaf with values in an abelian category, then  is actually a left exact functor. This means that it is possible to construct derived functors of

is actually a left exact functor. This means that it is possible to construct derived functors of  . These derived functors are called the cohomology groups (or modules) of F and are written

. These derived functors are called the cohomology groups (or modules) of F and are written  . Grothendieck proved in his Tohoku paper that every category of sheaves of abelian groups contains enough injective objects, so these derived functors always exist.

. Grothendieck proved in his Tohoku paper that every category of sheaves of abelian groups contains enough injective objects, so these derived functors always exist.

However, computing sheaf cohomology using injective resolutions is nearly impossible. In practice, it is much more common to find a different and more tractable resolution of F. A general construction is provided by Godement resolutions, and particular resolutions may be constructed using soft sheaves, fine sheaves, and flabby sheaves (also known as flasque sheaves from the French flasque meaning flabby). As a consequence, it can become possible to compare sheaf cohomology with other cohomology theories. For example, the de Rham complex is a resolution of the constant sheaf  on any smooth manifold, so the sheaf cohomology of

on any smooth manifold, so the sheaf cohomology of  is equal to its de Rham cohomology. In fact, comparing sheaf cohomology to de Rham cohomology and singular cohomology provides a proof of de Rham's theorem that the two cohomology theories are isomorphic.

is equal to its de Rham cohomology. In fact, comparing sheaf cohomology to de Rham cohomology and singular cohomology provides a proof of de Rham's theorem that the two cohomology theories are isomorphic.

A different approach is by Čech cohomology. Čech cohomology was the first cohomology theory developed for sheaves and it is well-suited to concrete calculations. It relates sections on open subsets of the space to cohomology classes on the space. In most cases, Čech cohomology computes the same cohomology groups as the derived functor cohomology. However, for some pathological spaces, Čech cohomology will give the correct  but incorrect higher cohomology groups. To get around this, Jean-Louis Verdier developed hypercoverings. Hypercoverings not only give the correct higher cohomology groups but also allow the open subsets mentioned above to be replaced by certain morphisms from another space. This flexibility is necessary in some applications, such as the construction of Pierre Deligne's mixed Hodge structures.

but incorrect higher cohomology groups. To get around this, Jean-Louis Verdier developed hypercoverings. Hypercoverings not only give the correct higher cohomology groups but also allow the open subsets mentioned above to be replaced by certain morphisms from another space. This flexibility is necessary in some applications, such as the construction of Pierre Deligne's mixed Hodge structures.

A much cleaner approach to the computation of some cohomology groups is the Borel–Bott–Weil theorem, which identifies the cohomology groups of some line bundles on flag manifolds with irreducible representations of Lie groups. This theorem can be used, for example, to easily compute the cohomology groups of all line bundles on projective space.

In many cases there is a duality theory for sheaves which generalizes Poincaré duality. See Grothendieck duality and Verdier duality.

Sites and topoi

André Weil's Weil conjectures stated that there was a cohomology theory for algebraic varieties over finite fields which would give an analogue of the Riemann hypothesis. The only natural topology on such a variety, however, is the Zariski topology, but sheaf cohomology in the Zariski topology is badly behaved because there are very few open sets. Alexandre Grothendieck solved this problem by introducing Grothendieck topologies, which axiomatize the notion of covering. Grothendieck's insight was that the definition of a sheaf depends only on the open sets of a topological space, not on the individual points. Once he had axiomatized the notion of covering, open sets could be replaced by other objects. A presheaf takes each one of these objects to data, just as before, and a sheaf is a presheaf that satisfies the gluing axiom with respect to our new notion of covering. This allowed Grothendieck to define étale cohomology and l-adic cohomology, which eventually were used to prove the Weil conjectures.

A category with a Grothendieck topology is called a site. A category of sheaves on a site is called a topos or a Grothendieck topos. The notion of a topos was later abstracted by William Lawvere and Miles Tierney to define an elementary topos, which has connections to mathematical logic.

History

The first origins of sheaf theory are hard to pin down — they may be co-extensive with the idea of analytic continuation. It took about 15 years for a recognisable, free-standing theory of sheaves to emerge from the foundational work on cohomology.

- 1936 Eduard Čech introduces the nerve construction, for associating a simplicial complex to an open covering.

- 1938 Hassler Whitney gives a 'modern' definition of cohomology, summarizing the work since J. W. Alexander and Kolmogorov first defined cochains.

- 1943 Norman Steenrod publishes on homology with local coefficients.

- 1945 Jean Leray publishes work carried out as a prisoner of war, motivated by proving fixed point theorems for application to PDE theory; it is the start of sheaf theory and spectral sequences.

- 1947 Henri Cartan reproves the de Rham theorem by sheaf methods, in correspondence with André Weil (see De Rham-Weil theorem). Leray gives a sheaf definition in his courses via closed sets (the later carapaces).

- 1948 The Cartan seminar writes up sheaf theory for the first time.

- 1950 The 'second edition' sheaf theory from the Cartan seminar: the sheaf space (espace étalé) definition is used, with stalkwise structure. Supports are introduced, and cohomology with supports. Continuous mappings give rise to spectral sequences. At the same time Kiyoshi Oka introduces an idea (adjacent to that) of a sheaf of ideals, in several complex variables.

- 1951 The Cartan seminar proves the Theorems A and B based on Oka's work.

- 1953 The finiteness theorem for coherent sheaves in the analytic theory is proved by Cartan and Jean-Pierre Serre, as is Serre duality.

- 1954 Serre's paper Faisceaux algébriques cohérents (published in 1955) introduces sheaves into algebraic geometry. These ideas are immediately exploited by Hirzebruch, who writes a major 1956 book on topological methods.

- 1955 Alexander Grothendieck in lectures in Kansas defines abelian category and presheaf, and by using injective resolutions allows direct use of sheaf cohomology on all topological spaces, as derived functors.

- 1956 Oscar Zariski's report Algebraic sheaf theory

- 1957 Grothendieck's Tohoku paper rewrites homological algebra; he proves Grothendieck duality (i.e., Serre duality for possibly singular algebraic varieties).

- 1958 Godement's book on sheaf theory is published. At around this time Mikio Sato proposes his hyperfunctions, which will turn out to have sheaf-theoretic nature.

- 1957 onwards: Grothendieck extends sheaf theory in line with the needs of algebraic geometry, introducing: schemes and general sheaves on them, local cohomology, derived categories (with Verdier), and Grothendieck topologies. There emerges also his influential schematic idea of 'six operations' in homological algebra.

At this point sheaves had become a mainstream part of mathematics, with use by no means restricted to algebraic topology. It was later discovered that the logic in categories of sheaves is intuitionistic logic (this observation is now often referred to as Kripke-Joyal semantics, but probably should be attributed to a number of authors). This shows that some of the facets of sheaf theory can also be traced back as far as Leibniz.

See also

- Coherent sheaf

- Holomorphic sheaf

- Gerbe

- Stack (descent theory)

References

- Bredon, Glen E. (1997), Sheaf theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 170 (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR1481706, ISBN 978-0-387-94905-5 (oriented towards conventional topological applications)

- Godement, Roger (1973), Topologie algébrique et théorie des faisceaux, Paris: Hermann, MR0345092

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1957), "Sur quelques points d'algèbre homologique", The Tohoku Mathematical Journal. Second Series 9: 119–221, MR0102537, ISSN 0040-8735

- Hirzebruch, Friedrich (1995), Topological methods in algebraic geometry, Classics in Mathematics, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR1335917, ISBN 978-3-540-58663-0 (updated edition of a classic using enough sheaf theory to show its power)

- Kashiwara, Masaki; Schapira, Pierre (1994), Sheaves on manifolds, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences], 292, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR1299726, ISBN 978-3-540-51861-7(advanced techniques such as the derived category and vanishing cycles on the most reasonable spaces)

- Mac Lane, Saunders; Moerdijk, Ieke (1994), Sheaves in geometry and logic, Universitext, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR1300636, ISBN 978-0-387-97710-2 (category theory and toposes emphasised)

- Martin, W. T.; Chern, S. S.; Zariski, Oscar (1956), "Scientific report on the Second Summer Institute, several complex variables", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 62: 79–141, MR0077995, ISSN 0002-9904

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1955), "Faisceaux algébriques cohérents", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series 61: 197–278, MR0068874, ISSN 0003-486X, http://www.jstor.org/view/0003486x/di961745/96p00036/0?currentResult=0003486x%2bdi961745%2b96p00036%2b0%2cFFFFFFFFFFFFEFAFBFFD07&searchUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.jstor.org%2Fsearch%2FBasicResults%3Fhp%3D25%26si%3D1%26gw%3Djtx%26jtxsi%3D1%26jcpsi%3D1%26artsi%3D1%26Query%3Dfaisceaux%2Bserre%26wc%3Don

- Swan, R. G. (1964), The Theory of Sheaves, University of Chicago Press (concise lecture notes)

- Tennison, B. R. (1975), Sheaf theory, Cambridge University Press, MR0404390 (pedagogic treatment)

External links

- Sheaf on PlanetMath