Presbyterianism

| Part of a series on Calvinism (see also Portal) |

|

|

|

| John Calvin | |

|

Background |

|

|

Distinctives |

|

|

Documents |

|

|

Influences |

|

|

Churches |

|

Presbyterianism refers to a family of Christian denominations within Calvinism. It evolved primarily in Scotland before the Act of Union in 1707. Most of the few Presbyteries found in England can trace a Scottish connection. Although some adherents hold to the theology of Calvin and his immediate successors, there are a range of theological views within contemporary Presbyterianism. Its theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Bible and the necessity of grace through faith in Christ.

Modern Presbyterianism traces its institutional roots back to the Scottish Reformation. Local congregations are governed by Sessions made up of representatives of the congregation, a conciliar approach which is found at other levels of decision-making (Presbytery, Synod and General Assembly). Theoretically, there are no bishops in Presbyterianism; however, some groups in Eastern Europe, and in ecumenical groups, do have bishops. The office of elder is another distinctive mark of Presbyterianism: these are specially commissioned non-clergy who take part in local pastoral care and decision-making at all levels.

The roots of Presbyterianism lie in the European Reformation of the 16th century, with the example of John Calvin's Geneva being particularly influential. Most Reformed churches who trace their history back to Scotland are either Presbyterian or Congregationalist in government.

In the twentieth century, some Presbyterians have played an important role in the Ecumenical Movement, including the World Council of Churches. Many Presbyterian denominations have found ways of working together with other Reformed denominations and Christians of other traditions, especially in the World Alliance of Reformed Churches. Some Presbyterian Churches have entered into unions with other churches, such as Congregationalists, Lutherans, Anglicans, and Methodists. However, others are more conservative, holding traditional interpretations of doctrines and shunning, for the most part, relations with non-Reformed bodies.

Contents |

History of Presbyterianism

Presbyterian denominations derive their name from the Greek word presbuteros (πρεσβύτερος), which means "elder." (Presbyterian church in Acts 14:23, 20:17, Titus 1:5).

Among the early church fathers, it was noted that the offices of elder and bishop were identical, and weren't differentiated until later, and that plurality of elders was the norm for church government. St. Jerome (347-420) "In Epistle Titus", vol. iv, said, "Elder is identical with bishop, and before parties multiplied under diabolical influence, Churches were governed by a council of elders." This observation was also made by Chrysostom (349-407) in "Homilia i, in Phil. i, 1" and Theodoret (393-457) in "Interpret ad. Phil. iii", 445.

Presbyterianism was first described in detail by Martin Bucer of Strasbourg, who believed that the early Christian church implemented presbyterian polity.[1] The first modern implementation was by the Geneva church under the leadership of John Calvin in 1541.[1]

Presbyterianism by Region[2]

Scotland

John Knox (1505-1572), a Scot who had spent time studying under Calvin in Geneva, returned to Scotland and led the Parliament of Scotland to embrace the Reformation in 1560 (see Scottish Reformation Parliament). The Church of Scotland was eventually reformed along Presbyterian lines, to become the national, established Church of Scotland.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the Acts of Union 1707 between Scotland and England guaranteed the Church of Scotland's form of government. However, legislation by the United Kingdom parliament allowing patronage led to splits in the Church, notably the Disruption of 1843 which led to the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. Further splits took place, especially over theological issues, but most Presbyterians in Scotland were reunited by 1929 union of the established Church of Scotland and the United Free Church of Scotland.

England

In England, Presbyterianism was established in secret in 1572. Thomas Cartwright is thought to be the first Presbyterian in England. Cartwright's controversial lectures at Cambridge University condemning the episcopal hierarchy of the Elizabethan Church led to his deprivation of his post by Archbishop John Whitgift and his emigration abroad. In 1647, by an act of the Long Parliament under the control of Puritans, the Church of England permitted Presbyterianism. The re-establishment of the monarchy in 1660 brought the return of Episcopal church government in England (and in Scotland for a short time); but the Presbyterian church in England continued in non-conformity, outside of the established church. By the 19th century many English Presbyterian congregations had become Unitarian in doctrine.

A number of new Presbyterian Churches were founded by Scottish immigrants to England in the 19th century and later. Following the 'Disruption' in 1843 many of those linked to the Church of Scotland eventually joined what became the Presbyterian Church of England in 1876. Some, that is Crown Court (Covent Garden, London), St Andrew's (Stepney, London)) and Swallow Street (London), did not join the English denomination, which is why there are Church of Scotland congregations in England such as those at Crown Court, and St Columba's, Pont Street (Knightsbridge) in London.

In 1972, the Presbyterian Church of England (PCofE) united with the Congregational Church in England and Wales to form the United Reformed Church (URC). Among the congregations the PCofE brought to the URC were Tunley (Lancashire) , Aston Tirrold (Oxfordshire) and John Knox Presbyterian Church, Stepney, London (now part of Stepney Meeting House URC) - these are among the sole survivors today of the English Presbyterian churches of the 17th century. The URC also has a presence in Scotland, mostly of former Congregationalist Churches. Two former Presbyterian congregations, St Columba's, Cambridge (founded in 1879), and St Columba's, Oxford (founded as a chaplaincy by the PCofE and the Church of Scotland in 1908 and as a congregation of the PCofE in 1929), continue as congregations of the URC and university chaplaincies of the Church of Scotland.

In recent years a number of smaller denominations adopting Presbyterian forms of church government have organised in England, including the International Presbyterian Church planted by evangelical theologian Francis Schaeffer of L'Abri Fellowship in the 1970s, and the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in England and Wales founded in the North of England in the late 1980s.

Wales

In Wales Presbyterianism is represented by the Presbyterian Church of Wales, which was originally composed largely of Calvinistic Methodists.

Ireland

Presbyterianism was brought by Scottish plantation settlers to Ulster who had been strongly encouraged to emigrate by James VI of Scotland, later James I of England. An estimated 100,000 Scottish Presbyterians moved to the northern counties of Ireland between 1607 and the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The Presbytery of Ulster was formed in 1642 separately from the established Anglican Church. Presbyterians, along with Roman Catholics in Ulster and the rest of Ireland, suffered under the discriminatory Penal Laws until they were revoked in the early 19th century. Presbyterianism is represented in Ireland by the Presbyterian Church in Ireland.

North America

- See also: Reformed Churches in North America

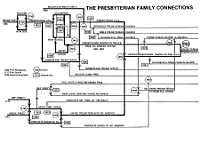

Even before Presbyterianism spread abroad from Scotland there were divisions in the larger Presbyterian family, some of which later rejoined only to separate again. In what some interpret as rueful self-reproach, some Presbyterians refer to the divided Presbyterian churches as the "Split P's".

In North America, because of past--or current--doctrinal differences, Presbyterian churches often overlap, with congregations of many different Presbyterian groups in any one place. The largest Presbyterian denomination in the United States is the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) (PC(USA)). Other Presbyterian bodies in the United States include the Presbyterian Church in America, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Presbyterian Church, the Bible Presbyterian Church, the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (ARP Synod), the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Westminster Presbyterian Church in the United States (WPCUS), and the Reformed Presbyterian Church in the United States (RPCUS). All the latter bodies, with perhaps the exception of the Cumberland Presbyterians, are theologically conservative and profess some degree of evangelicalism.

The territory within about a 50-mile (80 km) radius of Charlotte, North Carolina is historically the greatest concentration of Presbyterianism in the Southern U.S., while an almost-identical geographic area around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania contains probably the largest number of Presbyterians in the entire nation. With their members' traditional stress on higher education, the largest Presbyterian congregations can often be found in affluent, prestigious "uptown" suburbs of American cities.

The PC (USA), beginning with its predecessor bodies, has, in common with other so-called "mainline" Protestant denominations, experienced a significant decline in members in recent years; some estimates have placed that loss at nearly half in the last forty years.[3]

In Canada, the largest Presbyterian denomination – and indeed the largest Protestant denomination – was the Presbyterian Church in Canada, formed in 1875 with the merger of four regional groups. In 1925, the United Church of Canada was formed with the Methodist Church, Canada, and the Congregational Union of Canada. A sizable minority of Canadian Presbyterians, primarily in southern Ontario but also throughout the entire nation, withdrew, and reconstituted themselves as a non-concurring continuing Presbyterian body. They regained use of the original name in 1939.

Latin America

Presbyterianism arrived in Latin America in the 19th century. The biggest Presbyterian church is the Presbyterian Church of Brazil (Igreja Presbiteriana do Brasil [1]), which has around five hundred thousand members. In total, there are more than one million Presbyterian members in all of Latin America. Some Latin Americans in North America are active in the Presbyterian Cursillo Movement.

Africa

Presbyterianism arrived in Africa in the 19th century through the work of Scottish missionaries. The church has grown extensively and now has a presence in at least 23 countries in the region.[4] The Presbyterian Church of East Africa, based in Kenya is particularly strong with 500 clergy and 4 million members.[5] African presbyterian churches often incorporate diaconal ministries including social services, emergency relief, and the operation of mission hospitals. A number of partnerships exist between presbyteries in Africa and the PC(USA), including specific connections with Lesotho, Malawi, and South Africa, and Ghana. For example, the Lackawanna Presbytery, located in Northeastern Pennsylvania, has a partnership with a presbytery in Ghana.

Asia

In South Korea, a congregation in Seoul, Myungsung Presbyterian Church, claims to be the largest Presbyterian Church in the world. Presbyterians are the largest Protestant denomination in that country, and there are many Korean Presbyterians in the United States, either with their own church sites or sharing space in pre-existing churches.

In the mainly Christian Indian state of Mizoram, the Presbyterian denomination is the largest denomination; it was brought to the region with missionaries from Wales in 1894.

But prior to Mizoram, the Welsh Presbyterians (missionaries) started venturing into the north-east of India through the Khasi Hills (presently located within the state of Meghalaya in India) and established Presbyterian churches all over the Khasi Hills from 1840's onwards. Hence there is a strong presence of Prebyterians in Shillong (the present capital of Meghalaya) and the areas adjoining to it .The Welsh missionaries built their first church in Cherrapunji (aka Sohra) in 1846 which is also in Meghalaya and is renowned for being the wettest place on earth.(karikor)

Presbyterians participated in the mergers that resulted in the Church of North India and the Church of South India.

In Taiwan, the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan has been an important supporter of the use of Taiwanese languages (as opposed to Mandarin Chinese, which has become dominant since the Nationalists fled to the island) as a consequence of its advocacy of vernacular scriptures and worship services.[2]

There is also a Presbyterian Church in Lahore, Pakistan.

Oceania

In New Zealand, Presbyterian is the dominant denomination in Otago and Southland due largely to the rich Scottish and to a lesser extent Ulster-Scots heritage in the region. The area around Christchurch, Canterbury, is dominated philosophically by the Anglican (Episcopalian) denomination.

Originally there were two branches of Presbyterianism in New Zealand, the northern Presbyterian church which existed in the North Island and the parts of the South Island north of the Waitaki River, and the Synod of Otago and Southland, founded by Free Church settlers in southern South Island. The two churches merged in 1901, forming what is now the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand.

In Australia, Presbyterianism is the fourth largest denomination of Christianity with nearly 720,000 Australians claiming to be Presbyterian in the 2001 Commonwealth Census. Presbyterian churches were founded in each colony, some with links to the Church of Scotland and others to the Free Church, including a number founded by John Dunmore Lang. Some of these bodies merged in the 1860s. In 1901 the churches linked to the Church of Scotland in each state joined together forming the Presbyterian Church of Australia but retaining their state assemblies.

In 1977, two thirds of the Presbyterian Church of Australia, along with the Congregational Union of Australia and the Methodist Church of Australasia, combined to form the Uniting Church in Australia. The majority of the other third did not join due to disagreement with the Uniting Church's liberal views, though a portion remained due to cultural attachment.

The Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu is the largest denomination in the country with approximately one-third of the population of Vanuatu members of the church. The PCV (Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu) is headed by a moderator with offices in Port Vila. The PCV is particularly strong in in the provinces of Tafea, Shefa, and Malampa. The Province of Sanma is mainly Presbyterian with a strong Roman Catholic minority in the Francophone areas of the province. There are some Presbyterian people, but no organised Presbyterian churches in Penama and Torba both of which are traditionally Anglican. Vanuatu is the only country in the South Pacific with a significant Presbyterian heritage and membership. The PCV is a founding member of the Vanuatu Christian Council (VCC). The PCV runs many primary schools and Onesua secondary school. Although the church has lost several members due to the encroachment of American fundamentalist sects, the church is still strong especially in the rural villages. The PCV was taken to Vanuatu by missionaries from Scotland.

- See also: List of Presbyterian denominations in Australia

Characteristics of Presbyterianism

Presbyterians distinguish themselves from other denominations by doctrine, institutional organization (or "church order") and worship; often using a book of order, or 'Book of Forms' to regulate common practice and order. The origins of the Presbyterian churches were in Calvinism, which is no longer emphasized in some contemporary branches. Many branches of Presbyterianism are remnants of previous splits from larger groups. Some of the splits have been due to doctrinal controversy, while some have been caused by disagreement concerning the degree to which those ordained to church office should be required to agree with the Westminster Confession of Faith, which historically serves as an important confessional document - second only to the Bible, yet directing particularities in the standardization and translation of the Bible - in Presbyterian churches.

Presbyterians place great importance upon education and continuous study of the scriptures, theological writings, and understanding and interpretation of church doctrine embodied in several statements of faith and catechisms formally adopted by various branches of the church [often referred to as 'subordinate standards'; see Doctrine (below)]. It is generally considered that the point of such learning is to enable one to put one's faith into practice; some Presbyterians generally exhibit their faith in action as well as words, by generosity, hospitality, and the constant pursuit of social justice and reform, as well as proclaiming the gospel of Christ.

Church governance

Presbyterian government is by councils (known as courts) of elders. Teaching and ruling elders are ordained and convene in the lowest council known as a session or consistory responsible for the discipline, nurture, and mission of the local congregation. Teaching elders (pastors) have responsibility for teaching, worship, and performing sacraments. Pastors are called by individual congregations. A congregation issues a call for the pastor's service, but this call must be ratified by the local presbytery.

Ruling elders are usually laymen (and laywomen in some denominations) who are elected by the congregation and ordained to serve with the teaching elders, assuming responsibility for nurture and leadership of the congregation. Often, especially in larger congregations, the elders delegate the practicalities of buildings, finance, and temporal ministry to the needy in the congregation to a distinct group of officers (sometimes called deacons, which are ordained in some denominations). This group may variously be known as a 'Deacon Board', 'Board of Deacons' 'Diaconate', or 'Deacons' Court'.

Above the sessions exist presbyteries, which have area responsibilities. These are composed of teaching elders and ruling elders from each of the constituent congregations. The presbytery sends representatives to a broader regional or national assembly, generally known as the General Assembly, although an intermediate level of a synod sometimes exists. This congregation / presbytery / synod / general assembly schema is based on the historical structure of the larger Presbyterian churches, such as the Church of Scotland or the Presbyterian Church (USA) (PCUSA); some bodies, such as the Presbyterian Church in America and the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, skip one of the steps between congregation and General Assembly, and usually the step skipped is the Synod. The Church of Scotland has now abolished the Synod.

Presbyterian governance is practised by Presbyterian denominations and also by many other Reformed churches.

Doctrine

Presbyterianism is historically a confessional tradition, which means that the doctrines taught in the church are compared to a doctrinal standard. However, there has arisen a spectrum of approaches to "confessionalism." The manner of subscription, or the degree to which the official standards establish the actual doctrine of the church, turns out to be a practical matter. That is, the decisions rendered in ordination and in the courts of the church largely determine what the church means, representing the whole, by its adherence to the doctrinal standard.

Some Presbyterian traditions adopt only the Westminster Confession of Faith, as the doctrinal standard to which teaching elders are required to subscribe, in contrast to the Larger and Shorter catechisms, which are approved for use in instruction. Many Presbyterian denominations, especially in North America, have adopted all of the Westminster Standards as their standard of doctrine which is subordinate to the Bible. These documents are Calvinistic in their doctrinal orientation, although some versions of the Confession and the catechisms are more overtly Calvinist than some other, later American revisions. The Presbyterian Church in Canada retains the Westminster Confession of Faith in its original form, while admitting the historical period in which it was written should be understood when it is read.

The Westminster Confession is 'The principal subordinate standard of the Church of Scotland' (Articles Declaratory of the Constitution of the Church of Scotland II), but 'with due regard to liberty of opinion in points which do not enter into the substance of the Faith' (V). This formulation represents many years of struggle over the extent to which the confession reflects the Word of God and the struggle of conscience of those who came to believe it did not fully do so (e.g., William Robertson Smith). Some Presbyterian Churches, such as the Free Church of Scotland, have no such 'conscience clause'. For more detail, see the article of the Church of Scotland.

The Presbyterian Church USA has adopted the Book of Confessions, which reflects the inclusion of other Reformed confessions in addition to the Westminster documents. These other documents include ancient creedal statements, (the Nicene Creed, the Apostles' Creed), 16th century Reformed confessions (the Scots Confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, the Second Helvetic Confession, all of which were written before Calvinism had developed as a particular strand of Reformed doctrine), and 20th century documents (The Theological Declaration of Barmen and the Confession of 1967).

The Presbyterian Church in Canada developed the confessional document Living Faith [1984] and retains it as a subordinate standard of the denomination. It is confessional in format, yet like the Westiminster Confession, draws attention back to the original text of the bible.

Presbyterians in Ireland who rejected Calvinism and the Westminster Confessions formed the Non-subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland.

Worship

Presbyterian denominations who trace their heritage to the British Isles usually organise their church services inspired by the principles in the Directory of Public Worship, developed by the Westminster Assembly in the 1640s. This directory documented Reformed worship practices and theology adopted and developed over the preceding century by British Puritans, initially guided by John Calvin and John Knox. It was enacted as law by the Scottish Parliament, and became one of the foundational documents of Presbyterian church legislation elsewhere.

Historically, the driving principle in the development of the standards of Presbyterian worship is the Regulative principle of worship, which specifies that (in worship), what is not commanded is forbidden.[6]

Presbyterians traditionally have held the Worship position that there are only two sacraments:

- Baptism, in which they hold to the paedo-baptist (ie. Infant baptism as well as baptising unbaptised adults) and the Aspersion (sprinkling) or Affusion (pouring) positions, rather than the Immersion position

- The Lord's Supper (also known as Communion )

Over subsequent centuries, many Presbyterian churches modified these prescriptions by introducing non-biblical hymns, instrumental accompaniment and ceremonial vestments in worship. Still, there is not one fixed "Presbyterian" worship style. Although there are set services for the "Lord's Day", one can find a service to be evangelical and even revivalist in tone (especially in some conservative denominations), or strongly liturgical, approximating the practices of Lutheranism or Anglicanism (especially where Scottish tradition is esteemed), or semi-formal, allowing for a balance of hymns, preaching, and congregational participation (favored by probably most American Presbyterians).

Presbyterian Church architecture

Presbyterians believe that churches are buildings to support the worship of God. The decor in some instances may be austere so as not to detract from worship. In the 19th century, prosperous congregations built imposing churches, such as St Giles Cathedral in Scotland, Fourth Presbyterian in Chicago, Fifth Avenue Presbyterian in New York City, Shadyside Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, and many others. Usually a Presbyterian church will not have statues of saints, nor the ornate altar more typical of a Roman Catholic church. In a Presbyterian (Reformed Church) one will not usually find a Crucifix hanging behind the Chancel. However, one may find stained glass windows that depict the crucifixion, behind a chancel.

Main features

- Pulpit

- Chancel

- Celtic cross/Presbyterian cross

- Communion table

- Baptismal font

- Aisles

- Stained glass

- Religious art

- Lectern

- Banners

- Flags

Examples

- Fourth Presbyterian Church, Chicago, Illinois

- St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland

- Madison Ave Presbyterian, New York, New York

- St Mary's Presbyterian, West Virginia

- Cathedral of Hope, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- First Presbyterian, San Rafael, California

- Bel Air Presbyterian, Los Angeles, California

- Shadyside Presbyterian Church

- Christ Presbyterian Church; Canton, Ohio

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Presbyterianism, n." OED Online. Draft revision March 2007. Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 8, 2008 http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50187752.

- ↑ A detailed breakdown of Presbyterian and Reformed churches by region and country is available at Reformed Online.

- ↑ Layman.org "Big Losses Projected"

- ↑ PC(USA) - Worldwide Ministries - Africa

- ↑ PC(USA) - Worldwide Ministries: Kenya

- ↑ Westminster Confession of Faith, Chapter XXI, paragraph I

References

- Stewart J Brown. The National Churches of England, Ireland, and Scotland, 1801-46 (2001)

- William Henry Foote. Sketches of North Carolina, Historical and Biographical... (1846) - full-text history of early North Carolina and its Presbyterian churches

- Andrew Lang. John Knox and the Reformation (1905)

- William Klempa, ed. The Burning Bush and a Few Acres of Snow: The Presbyterian Contribution to Canadian Life and Culture (1994)

- Marsden, George M. The Evangelical Mind and the New School Presbyterian Experience (1970)

- Mark A Noll. Princeton And The Republic, 1768-1822 (2004)

- Frank Joseph Smith, The History of the Presbyterian Church in America, Reformation Education Foundation, Manassas, VA 1985

- William Warren Sweet, Religion on the American Frontier, 1783—1840, vol. 2, The Presbyterians (1936), primary sources

- Ernest Trice Thompson. Presbyterians in the South vol 1: to 1860; Vol 2: 1861-1890; Vol 3: 1890-1972. (1963-1973)

- Leonard J. Trinterud, The Forming of an American Tradition: A Re-examination of Colonial Presbyterianism (1949)

- Encyclopedia of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (1884)

- Articles Declaratory of the Constitution of the Church of Scotland

See also

- Christianity

- Reformed churches

- Protestant Reformation

- Scottish Reformation

- Religion in Scotland

- World Alliance of Reformed Churches

- Scots-Irish Americans

- Puritan's Pit

Confession of Faith:

- Westminster Confession of Faith

- Larger Catechism

- Shorter Catechism

- Directory of Public Worship

- Scots Confession

Controversies:

- Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy

- Vestments controversy

Churches

- List of Christian denominations#Reformed Churches

- St. Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, sometimes regarded as the mother church for world Presbyterianism

Colleges and seminaries

- Presbyterian universities and colleges

Sisterhood and Brotherhood Presbyterian/Reformed Communities

- Category:Presbyterian/Reformed religious communities

Sisterhood Emmanuel Monastery of the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon

- http://www.iona.org.uk/

People

External links

- Worship — Service for the Lord's Day (Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church), an article describing an order of worship typical of mainline English-speaking Presbyterian congregations.

- Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America

- Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church

- Presbyterian Church in America

- Presbyterian Church USA

- Orthodox Presbyterian Church

- Spanish Reformed Churches I.R.E.

- Mizoram Presbyterian Church, Mizoram, India (Mizo language)

Archives

- Historical Center of the Presbyterian Church in America, St. Louis, MO, USA

- Historical Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, Memphis, TN, USA

- Presbyterian Church Archives of Aotearoa, New Zealand, Opoho, Dunedin, New Zealand

- Foreign Missions Archives for the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa, New Zealand

- Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives and Records Office, Toronto, Canada

- Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA, USA

- Presbyterian Church in Ireland Archives, Belfast, Northern Ireland

- Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat