Porphyry (philosopher)

|

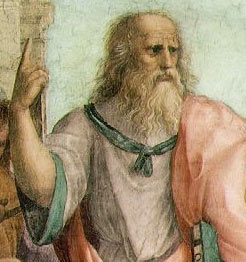

| Part of a series on Platonism |

| Platonic idealism |

| Platonic realism |

| Middle Platonism |

| Neoplatonism |

| Articles on Neoplatonism |

| Socratic dialogue |

| Socratic method |

| Platonic doctrine of recollection |

| Platonic epistemology |

| Theory of forms |

| Form of the Good |

| Participants in Dialogues |

| Socrates |

| Adeimantus |

| Alcibiades |

| Aristophanes |

| Callicles |

| Glaucon |

| Gorgias |

| Hippias |

| Protagoras |

| Parmenides |

| Theaetetus |

| Thrasymachus |

| Timaeus of Locri |

| Notable Platonists |

| Plotinus |

| Porphyry |

| Iamblichus |

| Proclus |

| Discussions of Plato's works |

| Dialogues of Plato |

| Chariot allegory |

| Allegory of the cave |

| Metaphor of the sun |

| Analogy of the divided line |

| Philosopher king |

| Plato's five regimes |

| Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? |

| The Myth of Er |

| Third Man Argument |

| Demiurge |

Porphyry of Tyre (Greek: Πορφύριος, c. A.D. 233–c. 309) was a Phoenician[1] Neoplatonic philosopher. He is important in the history of mathematics because of his Life of Pythagoras and his commentary on Euclid's Elements, used by Pappus when he wrote his own commentary.[2] Porphyry's Isagoge, or "Introduction" to Aristotle's "Categories", in Latin translation, was the standard textbook on logic for at least a millennium after his death (Barnes 2003).

Contents |

Biographical information

Porphyry's parents were Phoenician, and he was born Malchus ("king")[3] in Tyre. His teacher in Athens, Cassius Longinus, gave him the name Porphyrius ("clad in purple"), a punning allusion to the color of the imperial robes. Under Longinus he studied grammar and rhetoric. In 262 he went to Rome, attracted by the reputation of Plotinus, and for six years devoted himself to the study of Neoplatonism. Because of this he became suicidal.[4] On the advice of Plotinus he went to live in Sicily for five years to recover his health. On returning to Rome, he lectured on philosophy and completed an edition of the writings of Plotinus (who had died in the meantime) together with a biography of his teacher. Iamblichus is mentioned in ancient Neoplatonic writings as his pupil, but this most likely means only that he was the dominant figure in the next generation of philosophers. The two men differed publicly on the issue of theurgy. In his later years, he married Marcella, a widow with seven children and an enthusiastic student of philosophy. Little more is known of his life, and the date of his death is uncertain.

Eisagôgê, the "Introduction"

Porphyry is best known for his contributions to philosophy. Apart from writing the Aids to the Study of the Intelligibles, a basic summary of Neoplatonism, he is especially appreciated for his Introduction to Categories (Introductio in Praedicamenta), a very short work often considered to be a commentary on Aristotle's Categories, hence the title. According to Barnes (2003), however, the correct title is simply Introduction (είσγωγή)(Isagoge), and the book is an introduction not to the Categories in particular, but to logic in general, comprising as it does the theories of predication, definition, and proof. The Introduction describes how qualities attributed to things may be classified, famously breaking down the philosophical concept of substance into the five components genus, species, difference, property, accident.

As Porphyry's most influential contribution to philosophy, the Introduction to Categories incorporated Aristotle's logic into Neoplatonism, in particular the doctrine of the categories of being interpreted in terms of entities (in later philosophy, "universal"). Boethius' Isagoge, a Latin translation of Porphyry's "Introduction", became a standard medieval textbook in European schools and universities, which set the stage for medieval philosophical-theological developments of logic and the problem of universals. In medieval textbooks, the all-important Arbor porphyriana ("Porphyrian Tree") illustrates his logical classification of substance. To this day, taxonomy benefits from concepts in Porphyry's Tree, in classifying living organisms: see cladistics.

The Introduction was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa‘ from a Syriac version. With the Arabicized name Isāghūjī it long remained the standard introductory logic text in the Muslim world and influenced the study of theology, philosophy, grammar, and jurisprudence. Besides the adaptations and epitomes of this work, many independent works on logic by Muslim philosophers have been entitled Isāghūjī. Porphyry's discussion of accident sparked a long-running debate on the application of accident and essence.[6]

Philosophy from Oracles

Porphyry is also known as an opponent of Christianity and defender of Paganism; his defense of traditional religion, Philosophy from Oracles, written before the persecutions of Christians under Diocletian and Galerius, set out the basis for them:

- "How can these people be thought worthy of forbearance? They have not only turned away from those who from earliest time have been thought of as divine among all Greeks and barbarians... but by emperors, law-givers and philosophers— all of a given mind. But also, in choosing impieties and atheism, they have preferred their fellow creatures.[7] And to what sort of penalties might they not be subjected who... are fugitives from the things of their Fathers?"[8]

Whether or not Porphyry was the pagan philosopher opponent in Lactantius' Divine Institutes, written at the time of the persecutions, has long been discussed. Some of his writings were alleged to have been tampered with: a spurious version of Philosophy from Oracles bearing Porphyry's name was forged in which the author is made to write as a Christian. The fraudulent work was designed to be serviceable to Christianity; it was accepted by Eusebius and appealed to by apologists like Theodoret. St. Augustine was one of the first to reject it as a forgery. It was allowed to pass unchallenged by hosts of orthodox scholars in succeeding centuries; its character as a vulgar forgery was finally established by the laborious criticism of Dr Nathaniel Lardner in the 18th century.

Adversus Christianos

Of his Adversus Christianos (Against the Christians) in fifteen books, only fragments remain, as quotations adduced in order to be refuted.[9][10] In it, he famously is quoted as having said, "The Gods have proclaimed Christ to have been most pious, but the Christians are a confused and vicious sect." Counter-treatises were written by Eusebius of Caesarea, Apollinaris of Laodicea, Methodius of Olympus, and Macarius of Magnesia, but all these are lost.

Porphyry's identification of the Book of Daniel as the work of a writer in the time of Antiochus Epiphanes, is given by Jerome. Augustine and the 5th-century ecclesiastical historian Socrates of Constantinople, assert that Porphyry was once a Christian.

Other subjects

Porphyry was also opposed to the theurgy of his disciple Iamblichus. Much of Iamblichus' mysteries is dedicated to the defense of mystic theurgic divine possession against the critiques of Porphyry.

Porphyry was, like Pythagoras, an advocate of vegetarianism on spiritual and ethical grounds. These two philosophers are perhaps the most famous vegetarians of classical antiquity. He wrote the De Abstinentia (On Abstinence) and De Non Necandis ad Epulandum Animantibus (roughly On the Impropriety of Killing Living Beings for Food), advocating against the consumption of animals, and he is cited with approval in vegetarian literature up to the present day.

Porphyry also wrote widely on astrology, religion, philosophy, and musical theory. He produced a Philosophos istoria with vitae of philosophers that included a life of his teacher, Plotinus. His life of Plato from book iv exists only in quotes by Cyril of Alexandria.[11] His book Vita Pythagorae on the life of Pythagoras is not to be confused with the book of the same name by Iamblichus.

Works by Porphyry

- Ad Gaurum ed. K. Kalbfleisch. Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akadamie der Wissenschaft. phil.-hist. kl. (1895): 33-62.

- Contra Christianos, ed., Adolf von Harnack, Porphyrius, "Gegen die Christen,"15 Bücher: Zeugnisse, Fragmente und Referate. Abhandlungen der königlich prüssischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Jahrgang 1916: philosoph.-hist. Klasse: Nr. 1 (Berlin: 1916).

- Contra los Cristianos: Recopilación de Fragmentos, Traducción, Introducción y Notas E. A. Ramos Jurado, J. Ritoré Ponce, A. Carmona Vázquez, I. Rodríguez Moreno, J. Ortolá Salas, J. M. Zamora Calvo (Cádiz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz 2006).

- Corpus dei Papiri Filosofici Greci e Latini III: Commentarii (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1995). <# 6 and #9 may or may not be by Porphyry>

- De abstinentia ab esu animalium Jean Bouffartigue, M. Patillon, and Alain-Philippe Segonds, edd., 3 vols., Budé (Paris, 1979-1995).

- De Philosophia ex oraculis haurienda G. Wolf, ed. (Berlin: 1956).

- Epistula ad Anebonem, A. R. Sodano ed. (Naples: L'arte Tipografia, 1958).

- Fragmenta Andrew Smith, ed. (Stvtgardiae et Lipsiae: B. G. Tevbneri, 1993).

- The Homeric Questions: a Bilingual Edition Lang Classical Studies 2, R. R. Schlunk, trans. (Frankfurt-am-Main: Lang, 1993).

- Isagoge, Stefan Weinstock, ed. in Catalogus Codicum astrologorum Graecorum, Franz Cumon, ed. (Brussels, 1940): V.4, 187-228.

- Kommentar zur Harmonielehre des Ptolemaios Ingemar Duuring. ed. (Göteborg: Elanders, 1932).

- Opuscula selecta Augusts Nauck, ed. (Lipsiae: B. G. Tevbneri, 1886).

- Porphyrii in Platonis Timaeum commentarium fragmenta A. R. Sodano, ed. (Napoli: 1964).

- Porphyry, the Philosopher, to Marcella: Text and Translation with Introduction and Notes Kathleen O’bBien Wicker, trans., Text and Translations 28; Graeco-Roman Religion Series 10 (Atlanata: Schoalrs Press, 1987).

- Pros Markevllan Griechiser Text, herausgegeben, übersetzt, eingeleitet und erklärt von W. Pötscher (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969).

- Sententiae Ad Intelligibilia Ducentes E. Lamberz, ed. (Leipzig: Teubner, 1975).

- Vie de Pythagore, Lettre à Marcella E. des Places, ed. and trans. (Paris: Les Belles Lettre, 1982).

- La Vie de Plotin Luc Brisson, ed. Historie de l'antiquité classique 6 & 16 (Paris: Libraire Philosophique J. Vrin: 1986-1992) 2 vols.

- Vita Plotini in Plotinus, Armstrong, ed. LCL (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968), 2-84.

- To Marcella text and translation with Introduction and Notes by Kathleen O'Biren Wicker (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987).

Translations

- The Cave of the Nymphs in the Odyssey A revised text with translation by Seminar Classics 609, State University of New York at Buffalo, Arethusa Monograph 1 (Buffalo: Dept. of Classics, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1969).

- Isagoge Mediaeval Sources in Translation 16, E. Warren, trans. (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1975).

- Isagoge, Introduction, J. Barnes, trans. (Oxford, New York : Oxford University Press, 2003)

- Isagoge, J. Tricot, trans. (Paris: J. Vrin, 1947).

- Neoplatonic Saints: The Lives of Plotinus and Proclus Translated Texts for Historians 35 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000).

- On Abstinence from Killing Animals Gilliam Clark, trans. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000).

- On Aristotle's Categories Steven K. Strange, trans. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992).

- On the Cave of the Nymphs Robert Lamberton, trans. (Barrytown, N. Y.: Station Hill Press, 1983).

- The Organon or Logical Treatises of Aristotle with the Introduction of Porphyry Bohn's Classical Library 11-12, Octavius Freire Owen, trans. (London: G. Bell, 1908-1910), 2 vols.

- Porphyry Against the Christians, R. M. Berchman, trans., Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts 1 (Leiden: Brill, 2005).

- Porphyry’s Against the Christians: The Literary Remains R. Joseph Hoffmann, trans. (Amherst: Prometheus Books, 1994).

- Five Texts on the Mediaeval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham Paul Vincent Spade, trans. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994)

Notes

- ↑ George Sarton (1936). "The Unity and Diversity of the Mediterranean World", Osiris 2, p. 406-463 [430].

- ↑ Vita of Porphyry.

- ↑ For connotations of West Semitic MLK, see Moloch; compare theophoric names like Abimelech.

- ↑ Eunapius, Lives of the Philosophers

- ↑ "Inventions et decouvertes au Moyen-Age", Samuel Sadaune, p.112

- ↑ Encyclopedia Iranica, "Araz" (accident)

- ↑ That is, refusing to sacrifice to the gods and emperors ("atheism"), Christians have preferred the Christ, one of "their fellow creatures."

- ↑ The fragment, once thought part of Against the Christians, reassigned by R. Wilken in 1979 to Philosophy from Oracles, is quoted in Elizabeth DePalma Digeser, "Lactantius, Porphyry, and the Debate over Religious Toleration" The Journal of Roman Studies 88 (1998, pp. 129-146) p. 129.

- ↑ "Constantine and other emperors banned and burned Porphyry's work" (Digeser 1998:130).

- ↑ Letter of Constantine proscribing the works of Porphyry and Arius, To the Bishops and People, in Socrates, Historia Ecclesiastica, i.9.30-31; Gelasius, Historia Ecclesiastica, II.36; translated in Stevenson, J., (Editor; Revised with additional documents by W.H.C. Frend), A New Eusebius, Documents illustrating the history of the Church to AD 337 (SPCK, 1987).

- ↑ James A. Notopoulos, "Porphyry's Life of Plato" Classical Philology 35.3 (July 1940), pp. 284-293, attempted a reconstruction from Apuleius' use of it.

References

- Iamblichus: De mysteriis. Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Emma C. Clarke, John M. Dillon and Jackson P. Hershbell (Society of Biblical Literature; 2003) ISBN 158983058X.

- Dr. B. A. Zuiddam, "Old Critics and Modern Theology," Dutch Reformed Theological Journal (South Africa), xxxvi, 1995, № 2.

- Jonathan Barnes, Porphyry: Introduction (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2003).

- Karamanolis, George and Anne Sheppard (edd.). Studies on Porphyry (Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement, 98). London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London, 2007. v, 183 p.

External links

- Porphyry Malchus (mathematician) - entry in MacTutor History of Maths Archives]

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Porphyry, On Abstinence from Animal Food, Book I

- Porphyry, On Abstinence from Animal Food, Book II

- "On abstinence from animal food", Porphyry, Book III

- Porphyry, On Abstinence from Animal Food, Book III

- Porphyry, On Abstinence from Animal Food, Book IV

- Porphyry On the Cave of Nymphs

- Porphyry Isagogue

- Porphyry, On the Life of Plotinus

- Porphyry, Comments on the Book of Daniel

- Knowledge as Appropriation vs. Knowledge as Reprehension

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||